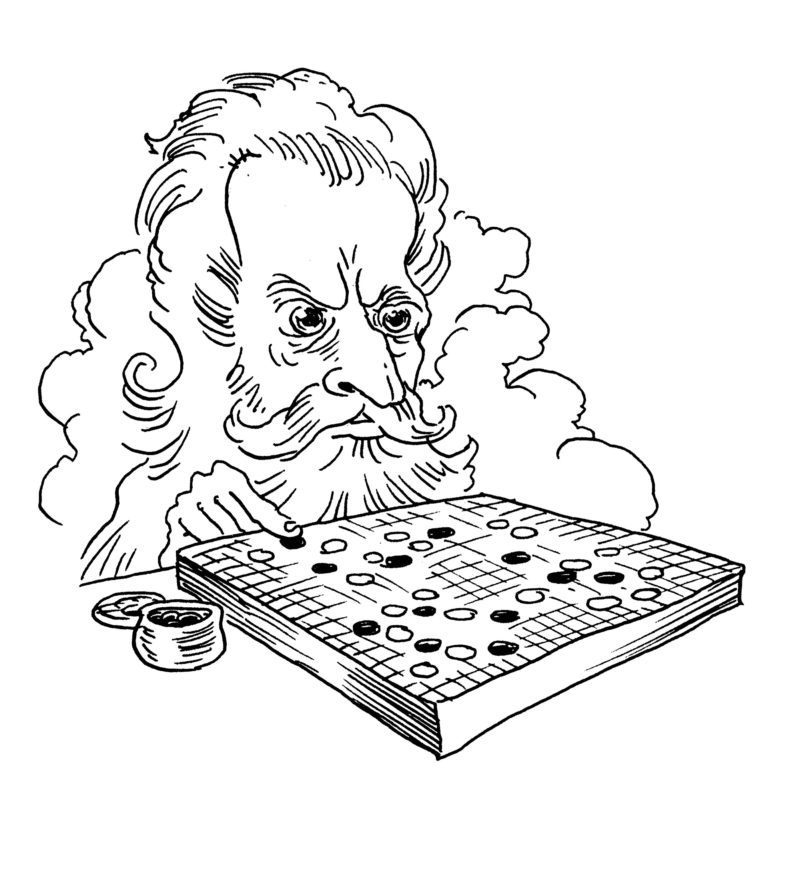

Science was supposed to have banished God, but he keeps turning up in our latest technologies. He is the ghost lurking in our data sets, the cockroach hiding beneath the particle accelerator. He briefly appeared three years ago in Seoul, on the sixth floor of the Four Seasons Hotel, where hundreds of people had gathered to watch Lee Sedol, one of the world’s leading go champions, play against AlphaGo, an algorithm created by Google’s DeepMind. Go is an ancient Chinese board game that is exponentially more complex than chess; the number of possible moves exceeds the number of atoms in the universe. Midway through the match, AlphaGo made a move so bizarre that everyone in the room concluded it was a mistake. “It’s not a human move,” said one former champion. “I’ve never seen a human play this move.” Even AlphaGo’s creator could not explain the algorithm’s choice. But it proved decisive. The computer won that game, then the next, claiming victory over Sedol in the best-of-five match.

The deep-learning program that developed AlphaGo represents something entirely new in the history of computing. Machines have long outsmarted us—thinking faster than us, performing functions we cannot—but not until now have they surpassed our understanding. Unlike Deep Blue, the computer that beat Garry Kasparov in chess in 1997, AlphaGo was not programmed with rules. It learned how to play go by studying hundreds of thousands of real-life matches, then evolved its own strategic models. Essentially, it programmed itself. Over the past few years, deep learning has become the most effective way to process raw data for predictive outcomes. Facebook uses it to recognize faces in photos; the CIA uses it to anticipate social unrest. These algorithms can now predict the onset of cancer better than human doctors, and can recognize financial fraud more accurately than professional auditors. When self-driving cars take over the streets, these algorithms will decide whose life to privilege in an accident. But such precision comes at the price of transparency: the algorithms are black boxes. They process data on a scale so vast, and evolve models of the world so complex, that no one, including their creators, can decipher how they reach conclusions.

Deep-learning systems comprise neural networks, circuits of artificial nodes that are loosely modeled on the human brain, and so one might expect that their reasoning would mimic our own. But AI minds differ radically from those evolved by nature. When the algorithms are taught to play video games, they invent ways to cheat that don’t occur to humans: exploiting bugs in the code that allow them to rack up points, for example, or goading their opponents into committing suicide. When Facebook taught two networks to communicate without specifying that the conversation be in English, the algorithms made up their own language. Deep learning is often called a form of “alien” intelligence, but alien does not mean wrong. In many cases, these machines understand our world far better than we do.

While Elon Musk and Bill Gates maunder on about AI nightmare scenarios—self-replication, the singularity—the smartest critics recognize that the immediate threat these machines pose is not existential but epistemological. Deep learning has revealed a truth that we’ve long tried to outrun: our human minds cannot fathom the full complexity of our world. For centuries, we believed we could hold nature captive, as Francis Bacon once put it, and force it to confess its secrets. But nature is not so forthcoming. If machines understand reality better than we can, what can we do but submit to their mysterious wisdom? Some technology critics have argued that our trust in such an opaque authority signals an end to the long march of the Enlightenment and a return to a time of medieval superstition and blind faith—what the artist and writer James Bridle calls “the new dark age.” Yuval Noah Harari has argued that the religion of “Dataism” will soon undermine the foundations of liberalism. “Just as according to Christianity we humans cannot understand God and His plan,” he writes, “so Dataism declares that the human brain cannot fathom the new master algorithms.” Of course, exposing the spiritual undertones of Silicon Valley is a self-defeating exercise when its leading researchers are starting their own cults. Anthony Levandowski, Google’s robotics wunderkind, recently founded a religion devoted to “the realization, acceptance, and worship of a godhead based on Artificial Intelligence.” He believes it is only a matter of time before AI assumes divine powers. “It’s not a god in the sense that it makes lightning or causes hurricanes,” he clarified in an interview. “But if there is something a billion times smarter than the smartest human, what else are you going to call it?”

Voltaire famously proclaimed that if God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him. But the truth is that we have always invented and reinvented God—not through science, but through theology—and the divinity of each age reveals the needs and desires of its human creators. The doctrine evolving around AI is not, in fact, a holdover from the Dark Ages. Rather, it resembles the theology that emerged alongside the birth of modernity. Just as Protestant reformers John Calvin and Martin Luther insisted upon God’s absolute sovereignty, our contemporary dogma grants machines unfettered power. Our role as humans is not to question the algorithmic logic but to submit to it.

*

All of this should be disconcerting to us humans. It is disconcerting, at least, to this human, who spent her early adulthood contending with a different form of superintelligence. Years ago, I was a student of hermeneutics at a small Chicago seminary, in which I’d enrolled for a simple, possibly idiotic, reason: I loved the teachings of Christ. He appears in four slim books. Meanwhile, the rest of the canon is ruled by his terrible alter ego: the vengeful potentate who destroys Job’s life on a wager and asks Abraham to kill his own son as a gratuitous test of loyalty. I wasn’t unfamiliar with these stories—they were told to us as children, but always in the colorful, vaguely fantastic spirit of folklore. In my freshman seminars, however, we read them as philosophical treatises on divine nature, and I was made to confront a question I’d never until then considered: how can you question an intelligence that is astronomically higher than your own? And to what authority can you appeal when this higher being claims that his abominable actions are perfect?

The biblical answer to these questions—the book of Job—was as unsettling as the questions themselves, mostly because it wasn’t an answer at all. The humanist in me could not help seeing Job as heroic. Throughout the bloody slog of the Old Testament, he stands alone in asking the question that seems obvious to modern readers: what is the purpose of God? Is his will truly good? Is his justice truly just? Job assumes the role of a prosecuting attorney and demands a cosmic explanation for his suffering. God dutifully appears in court, but only to humiliate Job with a display of divine supremacy. Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth? he thunders, then poses a litany of questions that no human can possibly answer. Job is so flummoxed, he denounces his own ability to reason. “Therefore I have declared that which I did not understand,” he says, “Things too wonderful for me, which I did not know.”

My classmates and I read the book alongside the commentary of John Calvin, who regarded it as a paean to God’s unfathomable will. Like Job, he argued, we must “submit ourselves to the single will of God, without asking a reason of his works, and especially of those works that surmount our wit and capacity.” Calvin’s God was completely Other, “as different from flesh as fire is from water.” We were not beings made in his image, but bugs who could never hope to fathom his motives, especially since our intellectual faculties were degenerated by sin. To some extent, this made redundant our work as theologians, since even the act of interpretation risked sullying the revelation’s perfection. Our professors taught us Calvin’s approach to hermeneutics, “brevitas et facilitas”: “brief and simple.” The lengthier the exegesis, the more likely it was to be tainted by human bias and by the desires of our wayward hearts. (Some professors took the more radical approach of Luther: “Scriptura sui ipsius interpres,” or “The text interprets itself.”) I was good at respecting the boundaries of this model, but privately, I began to question this divinity who acted outside the realm of human morals. I had always believed that God commanded us to love one another because love has intrinsic value—just as Socrates argues in Plato’s Euthyphro that the gods love piety because it is good, not the other way around. But according to Calvin, God’s goodness seemed to rest on nothing more than the Hobbesian rule that might makes right. At a certain point, I began to wonder whether an intelligence so far removed from human nature could truly have our best interests in mind.

Though I didn’t know it at the time, we have not always worshipped such a lofty God. Throughout the Middle Ages, Christians viewed him in quite a different light. Theology was still inflected with Platonism and rested on the premise that both God and the natural world were comprehensible to human reason. “All things among themselves possess an order, and this is the form that makes the universe like God,” Dante wrote in Paradiso. For Thomas Aquinas, the book of Job was not a parable about man’s limited intelligence, but an illustration of how humanity gradually becomes enlightened to the ultimate truth. It wasn’t until the fourteenth century that theologians began to argue that God was not limited by rational laws; he was free to command whatever he wanted, and whatever he decreed became virtuous simply because he decreed it. This new doctrine, nominalism, reached its apotheosis in the work of the Reformers. Like Calvin, Martin Luther believed that God’s will was incomprehensible. Divine justice, he wrote, is “entirely alien to ourselves.”

Now, years after I’ve abandoned my faith, I sometimes wonder what led these theologians to insist upon this formidable God. Did they realize that by endowing him with unlimited power, they were making him incomprehensible? In his 1941 book Escape from Freedom, Erich Fromm attributes the popularity of Luther’s and Calvin’s teachings to the breakdown of the feudal order and the rise of capitalism. Once the old authorities—the priest, the king—had been dissolved, the middle classes in Europe became terrified of their own freedom and hungry for some new authority. Protestant theology echoed their feelings of insignificance within the new order and promised to quell these doubts through the act of blind faith. “It offered a solution,” Fromm writes, “by teaching the individual that by complete submission and self-humiliation he could hope to find new security.”

This theology has been no less appealing to Christians in the twenty-first century. In fact, one of the reasons I struggled for so long to free myself from the church was that its doctrine offered an explanation for the overwhelming experience of modern life. The school I attended was in downtown Chicago, dwarfed by high-rises and luminous billboards that advertised the newest technological wonders. Walking those cavernous streets, I often felt myself to be an ant in a network of vast global structures—the market, technology—that exceeded my powers of comprehension. To my mind, even contemporary physics (the little I’d read), with its hypotheses on multiverses and other dimensions, echoed Calvin’s view that our bodies were faulty instruments ill-equipped to understand the absolute.

Whenever I tried to rationally object to God’s justice, I found myself in a position much like Ivan in The Brothers Karamazov, a novel I read during my second year of seminary. At one point Ivan tries, like Job, to build a case against God, only to confront a logical contradiction when he realizes that just as he cannot comprehend divine justice, he cannot understand non-Euclidean geometry (a new form of theoretical physics that would become the basis of Einstein’s theory of relativity). “I have come to the conclusion that, since I can’t understand even that,” he tells his brother Alyosha, a novice monk, “I can’t expect to understand about God… All such questions are utterly inappropriate for a mind created with an idea of only three dimensions.” In the end, Ivan does maintain his atheism, but it is a position he knows to be absurd and indefensible at its root. When I read the novel, in the throes of my own doubts, I immediately understood Dostoevsky’s larger point: rationalism, at least in the modern world, requires as much faith as religious belief.

*

Our predicament today is more complex than Ivan Karamazov’s: it is not only the natural world that is beyond our powers of comprehension, but also the structures of our own making. We now live in what has been called “the most measured age in history,” a moment when the data at our disposal—flowing from cell phones and cars, from the redwood forests and the depths of the oceans—exceeds all information collected since the beginning of time. For centuries, we looked to theories of moral philosophy to make decisions. Now we trust in the wisdom of machine intelligence. This is especially true within the realm of justice, where courts and law-enforcement agencies increasingly lean on predictive algorithms to locate crime hot spots, make sentencing decisions, and identify citizens who are likely to be shot. The programs can be eerily precise (one, PredPol, claims to be twice as accurate as human analysts in predicting where crimes will occur), but since their reasoning is often unknowable, the resulting decisions, however baldly problematic, cannot be examined or questioned.

In 2016, Eric Loomis, a thirty-four-year-old man from La Crosse, Wisconsin, was sentenced to six years in prison for evading the police. His sentence was partly informed by COMPAS, a predictive model that determines a defendant’s likelihood of recidivism. “You’re identified, through the COMPAS assessment, as an individual who is a high risk to the community,” the judge told him. Loomis asked to know what criteria were used, but was informed that he could not challenge the algorithm’s decision. His case reached the Wisconsin Supreme Court, which ruled against him. The state attorney general argued that Loomis had the same knowledge about his case as the court (the judges, he pointed out, were equally in the dark about the algorithm’s logic), and claimed that Loomis was “free to question the assessment and explain its possible flaws.” This was a rather creative understanding of freedom. Loomis was free to question the algorithm the same way that Job was welcome to question the justice of Jehovah.

When I first read about Loomis’s case, I thought of Job’s modern counterpart Josef K., the protagonist of Kafka’s The Trial. K., an anonymous bank clerk, is arrested one morning without being told the nature of his crime. As he tries to prove his innocence, he confronts a mystifying justice system that nobody, not even its clerks and emissaries, seems to understand. Northrop Frye called the novel “a kind of ‘midrash’ on the book of Job,” one that reimagines the opaque nature of divine justice as a labyrinthine modern bureaucracy. Like his biblical counterpart, K. eventually begins to doubt his own mind even as he is plagued by the conviction that there has been a mistake—that the allegedly infallible, all-knowing system is, at its core, unjust.

Loomis had good reason to doubt the wisdom of COMPAS. The same year he received his sentence, a ProPublica report found that the software was far more likely to incorrectly assign higher recidivism rates to black defendants than to white defendants. The algorithm suffers from a problem that has become increasingly common in these models—and that is, in fact, inherent to them. Because the algorithms are trained on historical data (for example, past court decisions), their outcomes often reflect human biases. Supposedly “neutral” machine-made decisions, then, end up reinforcing existing social inequalities. Many similar cases of machine bias have been well publicized: Google’s algorithms show more ads for low-paying jobs to women than to men. Amazon’s same-day delivery algorithms were found to bypass black neighborhoods. Half a century ago, Marshall McLuhan warned that tools are merely extensions of ourselves, amplifying our own virtues and flaws. Now we have created a godlike intelligence stained with the fingerprints of our own sins.

These errors have spurred demands for more transparency in AI. In 2016, the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation included in its stipulations the “right to an explanation,” declaring that citizens have a right to know the reason behind automated decisions that involve them. While no similar measure exists in the US, researchers are more likely these days to pay lip service to “transparency” and “explainability,” which are necessary for building consumer trust. Some have developed new methods that work in reverse to suss out data points that may have triggered the machine’s decisions. But these explanations are, at best, intelligent guesses. (Sam Ritchie, a former software engineer at Stripe, prefers the term narratives, since the explanations are not a step-by-step breakdown of the algorithm’s decision-making process but a hypothesis about reasoning tactics it may have used.) Programmers, who once saw themselves as didactic parents, training their algorithmic offspring in the ways of the world, have now become a holy priesthood devoted to interpreting the revelations of these runic machines the way Talmudic scholars once labored to decipher the mysteries of scripture.

One line of argument holds that the less we interfere with the machine’s decision-making—and the more inaccessible its logic becomes—the more accurate its output. Among true believers, this bizarre omnipotence is the ultimate goal. “We already have humans who can think like humans,” says Yann LeCun, the head of Facebook’s AI research; “maybe the value of smart machines is that they are quite alien from us.” There exists among the technological elite a brand of sola fide and sola scriptura, a conviction that algorithmic revelations are perfect and that any interpretation risks undermining their authority. “God is the machine,” says the researcher Jure Leskovec, summarizing the consensus in his field. “The black box is the truth. If it works, it works. We shouldn’t even try to work out what the machine is spitting out.”

Such arguments obscure an obvious truth, one I realized far too late in my own hermeneutical education: the refusal of interpretation is itself a mode of interpretation, a particular way of regarding revelations that are ambiguous by nature. Perhaps the more insidious problem—at least for us laypeople—is that the explanations we do receive are filtered through this technological priesthood. We do not speak directly to the whirlwind, but do our bidding with the intermediaries, who have devoted themselves, like Job’s friends, to defending the whims of this alien intelligence. Because these machines are being integrated into vast profit-seeking systems that are themselves opaque, it’s increasingly difficult to tell what information is being withheld from us, and why. (The COMPAS system that determined Loomis’s sentence was not, in fact, a black-box algorithm; it was developed by a private company and was protected by proprietary law.) There exist increasingly shadowy boundaries between machines that are esoteric by nature and those that are obscured to protect the powerful; between what can be rationally understood and what we are permitted to know. As the writer Kelly Clancy points out, “Without access to such knowledge, we will be forced to accept the decisions of our algorithms blindly, like Job accepting his punishment.”

*

I spent most of my seminary years engaged in an intellectual game of chess against the Calvinist God, searching for his weak spots, trying to demonstrate why his actions were immoral. Toward the end of my studies, I began exploring these arguments through formal exegesis, which my professors took an almost sadistic delight in discrediting. My papers came back lacerated with red ink, the marginalia increasingly defensive and shrill. god is sovereign, one professor wrote in block-caps. he doesn’t need to explain himself. I knew it was impossible to prove that God doesn’t exist (what cannot be decided in the affirmative, as Father Zossima puts it in The Brothers Karamazov, can never be decided in the negative), but I believed I could prove he was unjust, and I persisted in this quest for many years before I finally realized its futility: you cannot defeat God through rational argument any more than you can beat a superintelligent algorithm in a game of go. The outcome is decided even before your first move. My loss of faith, when it came, was not a triumph of reason over superstition but an act of emotional surrender. I could no longer worship this jealous, capricious God.

I suppose this is why my atheism, if it can be called that, has always felt tenuous, provisional. I have my rational justifications, which I defer to whenever I’m asked why I don’t believe. But I have never completely shaken the suspicion—an anxiety that tends to surface during long drives and sleepless nights—that there might be, as Ivan Karamazov suspects, another realm where Euclidean logic breaks down and human reason is revealed as merely one dimension of a universe that is far more bizarre than we can presently imagine. That’s not to say that the alternate dimension, if it does exist, would be the baroque spiritual battlefield described by writers in the sixth century BCE, or that the cosmic consciousness would be Jehovah. But then again, why not? If it could be anything, why not that? My atheism did not erase God as a necessary premise, but left behind a perceptual gap in the fabric of reality, a possibility I can still feel looming, in moments of unquiet, like some ontological ozone.

This isn’t my own private predicament. We’re all in it. The voluntarist theology that Luther and Calvin embraced ultimately paved the way for the Enlightenment and the rise of modern science. It also destroyed the idea that there exists an intrinsic connection between the human mind and the transcendent order. The ramifications of this shift—the via moderna, as it came to be called—are so vast, and so deeply ingrained in the DNA of Western rationalism, that it’s difficult to recognize its effects as effects at all. Nominalism led scientists to reject the existence of universals and inspired the profound doubt that characterized seventeenth- and eighteenth-century philosophy. (Descartes so distrusted his own mind that he believed even the laws of mathematics might be subject to God’s whims. It was not inconceivable, he imagined, that God somehow “brought it about that I too go wrong every time I add two and three or count the sides of a square, or in some even simpler matter, if that is imaginable?”) Even as modern science has shed its religious moorings, it remains haunted by the possibility that there exists a fundamental incongruity between the human mind and absolute reality. The gap is still there, looming over us like an eternal question mark. And now we are building a consciousness to fill it.

Fromm believed that science and religious faith are responses to the same problem: the anxiety stemming from the modern condition of doubt. One of the persistent modern myths, Fromm argues in Escape from Freedom, is “the belief that unlimited knowledge of facts can answer the quest for certainty.” When science fails to satisfy this need—which it inevitably must—people will seek it in the security of religious faith and authoritarian leaders. The same anxiety that drove sixteenth-century Europeans to the tyrannical God of Luther and Calvin, Fromm argues, led to the rise of modern fascism.

It is this promise of certainty that makes these algorithms so appealing—and also what makes them a threat to the edifice of liberal humanism. As Yuval Noah Harari points out in his book Homo Deus, humanism has always rested on the premise that people know what’s best for themselves and can make rational decisions about their lives by listening to their “inner voice.” If we decide that algorithms are better than we are at predicting our own desires, it will compromise not only our autonomy but also the larger assumption that individual feelings and convictions are the ultimate source of truth. We already defer to machine wisdom to recommend books and restaurants and potential dates; as the programs become more powerful, and the available data on us more vast, we may allow them to guide us in whom to marry, what career to pursue, whom to vote for. “Whereas humanism commanded: ‘Listen to your feelings!’” Harari argues, “Dataism now commands: ‘Listen to the algorithms! They know how you feel.’”

One could argue that such a future would be liberating. If nothing else, it would finally relieve us of the drudgery of neoliberalism’s endless corridors of choice. Our dependence on present-day algorithms, moreover, rarely feels like an act of compliance or blind submission. Or perhaps it’s merely that the things that are asked of us seem so vague and insubstantial: our data, our privacy. If we were going to object to the vast cathedral that has been erected around us, we would have done so after the National Security Agency leaks in 2012, or perhaps in early 2017, when we learned that millions of Facebook users had become unwitting pawns in a game of global power. At those times, we instead circulated the familiar apologies of the surveillance era. We insisted that we had nothing to hide and thus nothing to fear; that the system was impersonal and therefore benign; that we had known all along that this was happening—outrage was mere performance or the protest of the willfully naive. But in my own interactions with technology, I noticed something more disturbing. It was not merely that I didn’t mind being monitored; there was in fact some solace in knowing that an invisible intelligence was watching; that the thousands of keystrokes and likes and mindless purchases I had made over the years had not disappeared into the ether but were being logged by a system that understood all my desires and predilections. I sometimes convinced myself that by feeding the algorithms, I was contributing to a greater cause: the stream of human knowledge, that eternal babbling brook. I was creating, moreover, an imprint of my own consciousness, a virtual self that would one day be codified into a system of rules and recommendations so that I would no longer have to make these decisions at all.

*

Let’s say we follow the path charted out by our technological elite. It might look something like this: machine intelligence eventually supersedes humans in all areas of expertise: economic, military, and commercial. For a while, human experts oversee the algorithms, ensuring that they are not making errors, but soon they become so efficient that oversight becomes superfluous. By then, we will be completely dependent on these systems; the functions needed to keep them running will have evolved in complexity beyond human understanding, and it will be impossible even to turn them off. Shutting them down would be tantamount to suicide.

This is, incidentally, the future Ted Kaczynski envisioned in his 1995 manifesto, a prophecy that now reads, I regret to say, as prescient. This particular passage of “Industrial Society and Its Future” is eerily reasonable, absent the all-caps and polemical flourishes that mark other sections as the desperate work of a terrorist. Kaczynski argues that the common sci-fi scenarios of machine rebellion are off base; rather, humans will slowly drift into a dependence on machines, giving over power bit by bit in gradual acquiescence. “As society and the problems that face it become more and more complex and machines become more and more intelligent,” he predicts, “people will let machines make more of their decisions for them, simply because machine-made decisions will bring better results than man-made ones.”

Then he entertains an alternate scenario: maybe humans won’t hand the reins over to the machines completely. Perhaps the computers will remain under the control of a “tiny elite.” This could obviously lead to tyranny. The elite might decide to exterminate large portions of the human race, now economically irrelevant. On the other hand, he muses, “if the elite consists of soft-hearted liberals, they may decide to play the role of good shepherds to the rest of the human race.”

They will see to it that everyone’s physical needs are satisfied, that all children are raised under psychologically hygienic conditions, that everyone has a wholesome hobby to keep him busy, and that anyone who may become dissatisfied undergoes “treatment” to cure his “problem.” …[Human beings] may be happy in such a society, but they will most certainly not be free. They will have been reduced to the status of domestic animals.

So goes the logic of a madman. But when I revisited Kaczynski’s manifesto last year, I was intrigued by his descriptions of the “good shepherds.” They reminded me of the Grand Inquisitor in The Brothers Karamazov, who argues that the freedom to choose between good and evil is actually a curse. In place of the burdens of choice, the Inquisitor and his fellow priests create a system of childlike rituals—confession, indulgences—by which the laity can ascertain their salvation. The majority of people happily surrender their freedom in exchange for this easy assurance. “And they will be glad to believe our answer,” he boasts, “for it will save them from the great anxiety and terrible agony they endure at present in making a free decision for themselves.”

For what it’s worth, I am not alone in finding Kaczynski’s vision prescient. Back in 2000, the programmer Bill Joy quoted the same passage in his landmark essay for Wired, “Why the Future Doesn’t Need Us.” The piece is a twelve-thousand-word reckoning—one might say a crisis of faith—about the future of AI. Joy acknowledges that Kaczynski’s actions were “criminally insane,” but he finds merit in his argument. He took the passage to many of his friends in the robotics industry, only to find that they were unconcerned. They reiterated Kaczynski’s logic, but without the dystopian cast: these changes would happen gradually, they insisted. Nobody would protest.

For Joy, the matter is deeply personal: “I may be working to create tools which will enable the construction of the technology that may replace our species,” he realizes. “How do I feel about this? Very uncomfortable.” Joy worries not only about the potential for authoritarianism, but about the existential threats these machines pose. Machine intelligence, as he sees it, is a unique risk—more dangerous even than nuclear warfare, since it can, theoretically, develop the ability to self-replicate, at which point humans will lose control. Joy concludes his essay by arguing that the risks of artificial intelligence outweigh their potential usefulness and should be abandoned; humans needed to find some other outlet for their creative energies. His conclusion was radical at the time, but seems even more so today—essentially, Joy proposes that humans limit their pursuit of knowledge. This might seem irrational, he admits, but it is no more so than submitting to technologies that might irrevocably alter what it means to be human or, in the end, destroy us. Once we enter into such a bargain, we are no longer doing science but engaging in a process of ritual deification. “The truth that science seeks,” Joy writes, “can certainly be considered a dangerous substitute for God if it is likely to lead to our extinction.”

Since Joy issued his warning, nearly twenty years have passed. The risks he feared have not been addressed; in fact, the stakes have only been raised. If so few in the industry share his concern, it’s perhaps because they see themselves, like Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor and Kaczynski’s “good shepherds,” as custodians of a spiritual mission. The same Kaczynski passage that Joy confronted is quoted at length in Ray Kurzweil’s book The Age of Spiritual Machines. Kurzweil, who is now a director of engineering at Google, claims he agrees with much of Kaczynski’s manifesto but that he parts ways with him in one crucial area. While Kaczynski feared these technologies were not worth the gamble, Kurzweil believes they are: “Although the risks are quite real, my fundamental belief is that the potential gains are worth the risk.” But here, Kurzweil is forced to admit that his belief is just that—a belief. Just as Ivan Karamazov is forced to concede that his rationalism rests on an act of faith, Kurzweil admits that his conviction is “not a position I can easily demonstrate.”

This comes in a chapter that is written as a philosophical dialogue between Kurzweil and Molly, an imaginary computer algorithm with whom Kurzweil converses throughout the book and whose contributions, written in all-caps, serve as a foil for his arguments (e.g., GEE, ARE YOU SURE THIS IS SAFE?). Kurzweil outlines all the ways humans might benefit from emerging technologies: the material gains are obvious (economic advancement, extension of life spans). But these are merely secondary benefits, he tells Molly. The biggest potential gain that technology offers is spiritual: “I see the opportunity to expand our minds, to extend our learning, and to advance our ability to create and understand knowledge as an essential spiritual quest,” he says.

Molly says: “SO WE RISK THE SURVIVAL OF THE HUMAN RACE FOR THIS SPIRITUAL QUEST?”

Kurzweil answers: “Yeah, basically.”

*

Several centuries have passed since we first embarked on the quest of the Enlightenment, and perhaps it’s true, as critics fear, that its trajectory has come full circle. The journalist David Weinberger has argued that AI, and deep-learning algorithms in particular, have finally revealed our human limitations. “We thought knowledge was about finding the order hidden in the chaos,” he writes. “We thought it was about simplifying the world. It looks like we were wrong. Knowing the world may require giving up on understanding it.” But perhaps these technologies have merely revealed the faulty premise that has undergirded the rationalist project since its inception: that empirical truth can solve our modern anxieties. Science, as Fromm said, cannot give humanity the sense of meaning it ultimately craves. He believed that ethical and moral systems must be rooted in human nature and human interests, and that science, which searches for objective reality, is merely a way of evading this responsibility. “Man must accept the responsibility for himself and the fact that only by using his own powers can he give meaning to his life,” he writes in Man for Himself. “But meaning does not imply certainty; indeed, the quest for certainty blocks the search for meaning.” Until we are willing to confront questions of ultimate meaning, Fromm predicted, we will continue to seek certainty outside our own human interests—if not in science, then in religion or in the seductive logic of authoritarian creeds.

The Enlightenment has been our single, long-winded response to the tyrannical God of Job. Perhaps we need a new approach, one that begins with a less self-serious reading of that ancient poem. Plenty of theologians have read the story atheistically, as an allegory about our tragic—or perhaps comic—inability to fathom the infinite. G. K. Chesterton memorably pointed out that when God appears in the whirlwind, he seems just as baffled as Job is by the bizarre universe he has created, which is full of strange fauna, monstrous beasts, and senseless suffering. “The maker of all things is astonished at the things he has Himself made,” Chesterton writes. Personally, though, I prefer Slavoj Žižek’s paraphrasing. He imagines God saying to Job: “Look at all the mess that I’ve created, the whole universe is crazy, like, sorry, I don’t control it.”

There’s a robust school of theologians who conceived of a God with attenuated powers. They understood that a truly humanistic faith demands a deity with such limits. This doctrine requires that humans relinquish their need for certainty—and for an intelligence who can provide definitive answers—and instead accept life as an irreducible mystery. If science persists in its quest for superintelligence, it might learn much from this tradition.