Scroll

Scroll

Aside Affects

December 1st, 2021 | Issue one hundred thirty-eight

Digressions on the art and politics of the rhetorical aside

In January 2021, the Bureau of Labor Statistics released its monthly report “The Employment Situation.” As might have been expected ten months after the World Health Organization declared a global pandemic, the news was not good: 140,000 jobs had been lost the previous month. This wasn’t the worst of it; headlines seized on the fact that every one of those lost jobs had belonged to a woman. “The US economy lost 140,000 jobs in December. All of them were held by women” (CNN Business); “Women account for 100% of jobs lost in December” (CNBC); “Women accounted for 100% of the 140,000 jobs shed by the U.S. economy in December” (Fortune). The reports, though staggering, at the very least sounded the alarm on something that women knew and feminism had foreseen: in crisis, the nation disposed of its backbone.

Claire Ewing-Nelson, of the National Women’s Law Center, broke down the report: Women had lost 156,000 jobs in December 2020 while men had gained 16,000: a net loss, and one that was not borne equally. But this was not the whole story. Just as the overall unemployment rate conceals disparities across gender lines, racial difference is further concealed within women’s rates of unemployment. Ewing-Nelson noted that the overall rate “masks even higher rates for Black women, Latinas, and other demographic groups,” such as women with disabilities and women between the ages of twenty and twenty-four. Below their headlines, most outlets enumerated this more detailed round of numbers, such as New York magazine’s The Cut, which reported that the economic downturn “has weighed heaviest on women of color” and “white women did not experience these trends as severely.” CNN, however, displayed the stratum more candidly: “Blacks and Latinas lost jobs in December, while White women made significant gains.” [1] The “women” making the headlines, it seemed, were not the same women who were losing jobs.

This sounded about right. What’s more, it aligned with boilerplate wisdom on the plights of “women” and “women of color,” respectively—imagined as orders of magnitude. Whatever can be said happens to “women” happens “especially,” “particularly,” “most,” and “worst” when color—“of color”—shows up. When the media documents non-white women this way, does it make them a part of the whole? Or apart from it? The “women” who lost jobs were not white, but the “women” imagined by the headlines must be; if women of color were the story, there would be no need for such asides. Women of color are women, but if that were true, one would expect we needn’t be reminded of it with such frequency. Gender was not meant for all [2].

Here we see a version of a familiar technique: A detail professing inclusiveness is squirreled away as secondary information. An article takes note of the less fortunate, allows a brief pause for the further disadvantaged, and moves on with its premise, undeterred by this dispensable material. The inclusion excludes. Mentions in passing read rather like the inversion of how the story should be told.

At the theater, on television, in books, audiences love an aside. But what is there, exactly, that’s worth loving? In early episodes of Sex and the City, Carrie Bradshaw enjoys a short-lived affair with the fourth wall. “How the hell did we get into this mess?” she asks the viewer, typing at her desk between frosty-lipped drags on a Marlboro Light. The iconic geometry of keyboard, cig, and voice-over would remain (mostly) throughout the series, but after fifteen episodes, viewers no longer had the pleasure of meeting Carrie eye-to-eye [3]. Apparently, Michael Patrick King (executive producer, writer, director) did not like this direct manner of discoursing with the audience. “I want to believe this,” he said. “I believe her. I think she’s the real thing. But whenever she turns to the camera, I no longer believe this. Can we stop that?”

Dramatic asides are not always so dramatic as to break the fourth wall. But they are spoken to be heard. What’s a stage whisper, after all, without an audience? Iago, Othello’s smooth operator, shan’t conceal his doings from us, his captive onlookers: “He takes her by the palm: ay, well said, whisper: with as little a web as this will I ensnare as great a fly as Cassio. Ay, smile upon her, do; I will gyve thee in thine own courtship.” In Sex and the City, Carrie’s voice-overs stayed put as the implied contents of her columns, but her to-camera asides, according to King, were unbelievable. This suggests something distrustful about an aside; presumably a form of disclosure, they might also make for a sly means of withholding.

In the house of fiction (and of nonfiction), asides are constructed with a different architecture. Many critics would call to mind Nabokov’s rhetorical devices; a passage early in Lolita encloses this famous pair of parenthetical asides:

My very photogenic mother died in a freak accident (picnic, lightning) when I was three, and, save for a pocket of warmth in the darkest past, nothing of her subsists within the hollows and dells of memory, over which, if you can still stand my style (I am writing under observation), the sun of my infancy had set.

The acute perfection—“arresting off-handedness, the cadence, the sonic double-mirroring… the simplicity”—of the first parenthetical ought not, writer Emily Temple writes, to overshadow the effects of the following pair, which operates as a “comment on the comment.” Apology for style loses some humility by that aside, which regards the character’s present circumstance and darkly imparts its meaning. The aside is put to similar use in this moment in White Teeth, by Zadie Smith:

It is only this late in the day, and possibly only in Willesden, that you can find best friends Sita and Sharon, constantly mistaken for each other because Sita is white (her mother liked the name) and Sharon is Pakistani (her mother thought it best—less trouble).

At their best, asides take a funambulist’s stroll between surplus and restraint. Smith’s first set of parentheses primes an alert reader versed in the lingua franca of evolving empire to understand what kind of household produces a white daughter with a Hindu name. Smith’s second set of parentheses even contains an additional aside offset by an em dash—a comment upon a comment upon a comment. Its stylized brevity, much like “(picnic, lightning),” winks at a more rebellious commentary. Its signaled gratuitousness—that the author could have withheld it—piques the attention all the more.

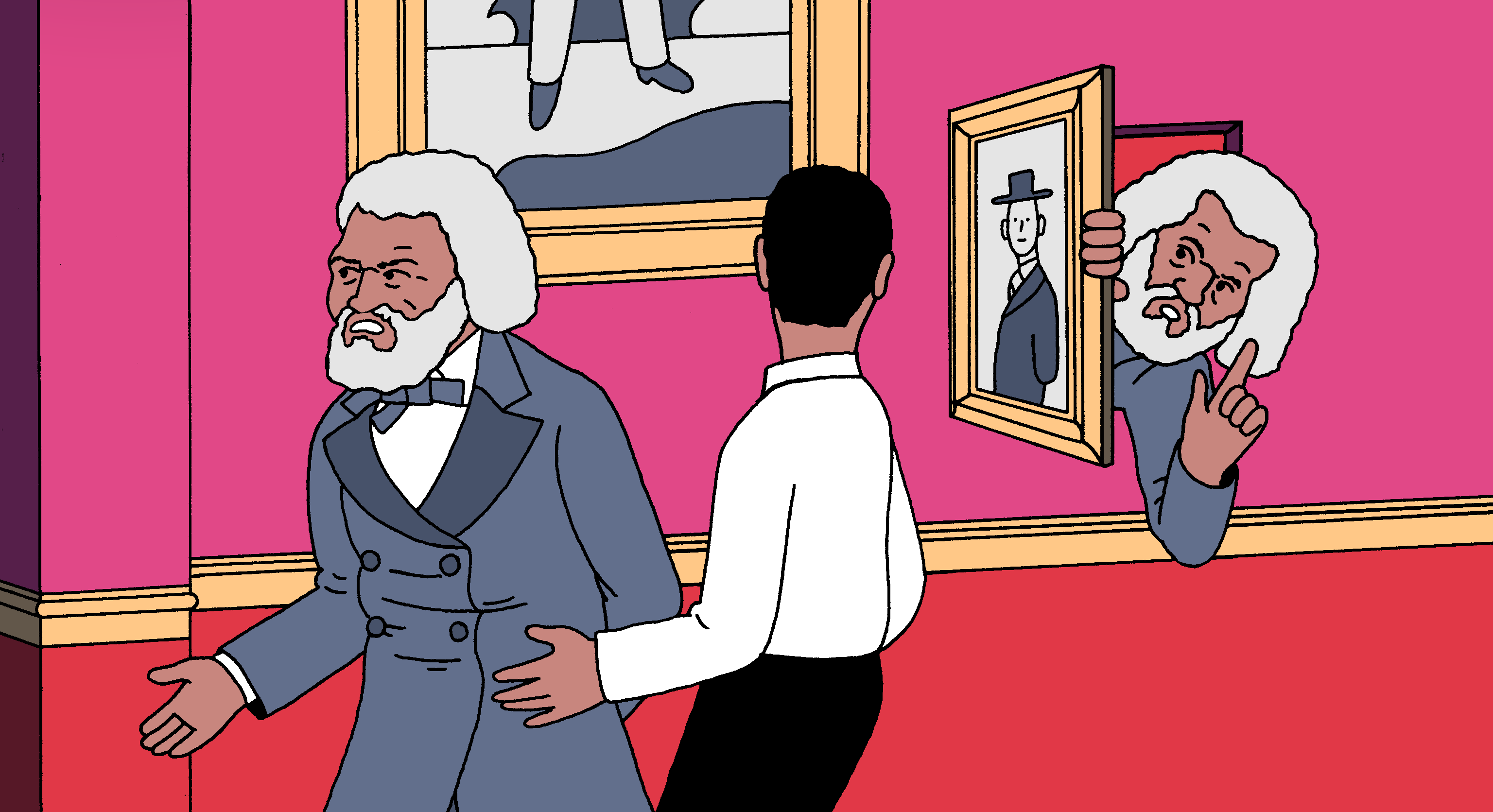

In Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself, asides arrive like small revisions, steadying the course of reader sentiment that, even at its most benevolent, still requires practice to identify the plight of the slave. Douglass, keen on the pernicious mythology of benevolent slaveholders, writes:

I soon found Mr. Freeland a very different man from Mr. Covey… The former (slaveholder though he was) seemed to possess some regard for honor, some reverence for justice, and some respect for humanity.

The aside reassembles Mr. Freeland’s lesser evil, emphasis changed from adjective to noun. Mr. Freeland was not like Mr. Covey, a religious fanatic who was known as a “nigger-breaker”; by contrast, Freeland “was what would be called an educated southern gentleman.” He owned a mere two slaves, and while “very passionate and fretful,” was “exceedingly free from those degrading vices” known to men like Covey. And yet he, like Covey, was, crucially and definitionally, a slaveholder. With the momentum of contrasts between the men tempered, the cautionary additive “some” juts into focus: “some regard,” “some reverence,” “some respect.”

Between Douglass’s first autobiography and his second—My Bondage and My Freedom, published in 1855—the asides pile up. Some are simply clarifying or offer factual elaboration. Other moments, much as in White Teeth, create the occasion for cool suggestion, and at times derision, in a style Namwali Serpell might call “black nonchalance”: “(what slaveholders would call wicked)”; “(as the slaveholders regard it)”; “(as was sometimes said of him)”; “(she had then given me no reason to fear)”; “(I write from sound, and the sounds on Lloyd’s plantation are not very certain.)”

Black nonchalance, Serpell writes, “performs nonreaction.” Raised on “the double consciousness, double meanings, double dealings required to navigate the intricate labyrinth of racism and its seemingly infinite threat of violence,” black nonchalance, she says, walks the tightrope with style. It is fitting that the aside would flourish in My Bondage and My Freedom, Douglass’s revisitation of his story ten years after the tightly coiled instrumentalism of the first, out of which he made himself the most popular slave alive. Not that My Bondage and My Freedom was spared of purpose. But it cannot be a coincidence that within the freer text, freed enough for sermons on the prejudice of the North that granted him succor, Douglass’s language finds freedom to do other things too. Subordinated by the main business of political memoir, yet raised above the level of subtext, Douglass’s asides are sly; they wink and conceal through disclosure [4]. Nonchalance “doesn’t revolutionize or fight the power,” Serpell writes. “… Nonchalance doesn’t step forward or turn its back. It loiters, hangs, leans, brushes past.”

If a parenthetical can be art, how about footnotes [5], or what gets loaded between two em dashes? Digressions, we could call them; sub and text but not subtext, much like an aside. Glyph, by Percival Everett, reanimates academic rituals even as it taunts them. The first-person protagonist is Ralph, an infant with remarkable brain power who devours great works of literature and theory—as well as more mundane works, such as a service manual for a Maytag washing machine—and has an equivalent mental grasp of and the manual dexterity for writing. He has no interest, meanwhile, in speech. Ralph’s regular use of footnotes dances upon the convention among peer-reviewed journals of keeping notes of the “discursive” type to a minimum. His footnotes run the gamut of elaboration, extrapolation, explanation, snark, and inquiry—various versions of comment on the comment. He quotes the poetry of Thomas Moore, riffs on “that Derrida guy,” and speculates—or, given his audience, gossips—about those around him. At one point he laments his reluctance to dishonor a book by throwing it and thereby raising the necessary fuss that might alert his parents to a kidnapping in progress. “I say this even though one of the texts in my crib at the time was Harold Bloom’s A Map of Misreading,” the footnote reads dryly.

This side-mouthed tone is perhaps exactly the sort that formal academic venues wish to curtail. But these sorts of asides, inasmuch as they preoccupy a writer’s mind and gradually encumber their drafts, can be informative. An adviser once encouraged me to heed the asides that nagged my work and others’. What’s there might be art or snark or the quiet insurrection that need not blow its cover; or there might be something that needs telling, escaping the rote obligations of the main story like the opening of a pressure valve.

It’s become fashionable to declare that new voices should be heard and that diverse stories should be told, and under these uncreative conditions, the text and subbed text of media narratives groan. Gleaming whiteness unaddressed as such won’t stand, and so someone must smudge the canvas. A pocket of text reserved for those further disadvantaged. An article on loitering, say, will take care to mention that Black and Brown folks are often penalized by anti-loitering laws, but such an aside leaves out the fact that the Brown loiterer is not one example but the prototype. The ethics of the thing protest too much. It’s “women and people of color.” It’s “women and femmes.” Jules Gill-Peterson, in her essay on trans pessimism, asks after the misty “trans woman of color” whose life in print is only an enhancement for other things, a summoning that suppresses whatever lives happen behind the rumor. An aside to be cast aside. “The trans woman of color whose life is invoked is always putative,” Gill-Peterson writes. “She’s no fact. Who is she? How do you know her? I know why Chase Bank, or Sephora[,] pretends to know her. But you? What’s your excuse?”

The ethical aside is an interruption—the beat before everyone gets on with their lives. Journalists signal that they have done their due diligence in reaching out to all parties with the inclusion of “(X declined to comment for this article)” in reported investigations; the ethical aside, likewise, says that the author has indeed thought of and considered the conditions of those excluded by their primary interests [6]. There’s someone else out there, it acknowledges, even as the story as written depends on their disavowed existence.

But an aside can be a beautiful place to take up residence. Counternarratives, by John Keene, is full of experiments. One story begins in 1754, with the birth of a slave named Zion. Its title, “An Outtake from the Ideological Origins of the American Revolution,” references a Pulitzer Prize–winning study of the revolution published in the ’60s that remains, as scholar Eric Slauter has written, “an inescapable citation, whether superficial or substantive.” Per its stated genre—the outtake—Keene’s story takes place outside the bounds of the political papers that occupy the study’s canonized history. Instead, we have the life et cetera of Zion, who again and again escapes from and is re-ensnared within an as-yet nation’s slave system. His singular rebellions chart the course of the latter 1700s, documented in offenses arraigned by courts throughout the Massachusetts Bay Colony and counted in stolen bounties of rum, shillings, and mutton. The narrator relates the facts of Zion placidly, as though relating the weather. It is no great deed to name the date of Zion’s final capture, September 17, 1774, the only event noted that year. Every now and then, the story glances at something elsewhere—“great changes were blowing through streets of the colonial capital”—but it is a brief thought, not worthy of much attention. In this story, it is the characters of that other insurrection, the American Revolution, who are hushed and held aside; what remains is Zion. There’s room for more than one revolt, but the other will quiet itself for now.

- This assessment comes from a section of the report’s data separate from that which reported the seasonally adjusted 156,000 total non-farm jobs lost; household survey data showed that the number of employed white women age twenty and older increased between November and December 2020, while the number of Black and Latina women decreased. Asian women were lumped together with Asian men.

- See: Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861); Hortense J. Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book” (1987); Kimberlé Crenshaw, “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color” (1991); Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts” (2008); and C. Riley Snorton, Black on Both Sides: A Racial History of Trans Identity (2017).

- The last such occurrence is an early season 2 episode called “The Freak Show.” Carrie has watched her date, “the man who steals cheap used books for no reason,” slip a paperback into his pants. Cut to a close-up of Carrie at her most Carrie: “OK, now I was afraid,” she tells us with her trademark cringe (all lips and brow).

- Not all asides are expressions of art or style; they are also a notorious place for cheap shots. In a chapter of Sociology for the South, or the Failure of Free Society, published a year prior to My Bondage and My Freedom, snotty George Fitzhugh gestures toward “the ladies, all of whom love poetry, (though none of them can write it).”

- Endnotes, meanwhile, sit at the back of the book, blissfully ignorant of whether a reader will seek them out.

- As though written from fear, not that they are misguided in their premise, but that someone online with more followers will tap them on the proverbial shoulder with Funny how you can write a whole article about… without once mentioning…