In her 2010 book Nox, the poet and classicist Anne Carson advises, “If you are writing an elegy begin with the blush.” Her suggestion confuses me: Blushing seems like an inappropriate reaction to mortality. Its delicate ephemerality gets blown out of the water by death as pure destination, as everybody-out, last-stop-on-the-line finitude. If nothing else, Carson’s words are incongruous on chromatic terms; I have never known anyone to grieve in pink. Yet in the same work she asks us, “Why do we blush before death?,” and her question prompts a reflexive follow-up: Do we really?

Something about the blush pervades matters we otherwise regard as serious and profound. It appears, at times, to sinister effect. When the German anthropologist Johann Blumenbach created his classification system for the races, placing his own at the top, his first justification was the erroneous notion that only white people could blush: “The redness of the cheeks in this variety is almost peculiar to [them]… it is but seldom to be seen in the rest.” Sir Charles Bell, a nineteenth-century British anatomist, wrote that in the blush “we perceive an advantage possessed by the fair family of mankind, and which must be lost to the dark.”

Death, power, and, of course, sex—the blush seeps into all. As with weeping or fainting, it holds out the promise of a body that undermines itself, that can overwhelm a person into revealing certain physical truths.

I am not white, and I do not blush visibly. Recently, I picked up the book Blush, which studies the phenomenon of blushing through a pairing of text from the writer Jack Robinson and images by the artist Natalia Zagórska-Thomas. I was surprised by the jealousy I felt reading about Robinson’s experience of chronic blushing:

“The moment when, having walked out of the shop with my pint of milk, I realise I haven’t paid. The moment when the person on the Tube I’ve been staring at looks straight back at me. The moment when I realise that I am being stared at… The moment when, having avoided being knocked over by a bus by a matter of millimetres, I realise that could so easily have been the end, but isn’t.”

Why do we blush before death?

If Blush teaches us anything, it’s that kitsch should not be underestimated. Cuteness can sicken an audience if it’s allowed to splash too freely in its own excesses. Robinson’s mild-mannered tone curdles in the presence of Zagórska-Thomas’s unsettling photographs, which seem intent on excavating the obscenities that roil under any dainty, lacquered surface. In this sense, the book constantly points to blushing’s abiding context, that of the tactile and libidinous body. One image shows long maroon hairs sprouting from a toothbrush; another features a white briefcase that has split open to reveal a lewdly magenta interior. These images suggest that fascination with the blush is perverse. Its “impure and imprecise” emotions vibrate, magnetized, between the poles of sex and willful denial.

I understand that there are some people who blush and hate it, who feel the loss of control as an existential devastation. I have watched YouTube videos of fair teenagers crying as they testify to this experience of exposure before others. Erythrophobia, the fear of blushing, is a ghastly somatic loop in which dread of the body’s outburst almost always guarantees its arrival. “The place where my discomfort chooses to display itself is the place that is most visible to others,” writes Robinson. “Never underestimate a blush’s sense of humor.”

I don’t know if I have ever experienced moments like these, when the mind becomes specially attuned to the high-frequency static of the body and is, in fact, temporarily possessed by it. Narrative, however, opens a window for the uninitiated. In eighteenth-century literature, which dealt with the blush more obsessively and for far longer than early science did, the assumed sincerity of the blush was such that it could function as gestural synecdoche. Unlike mannerisms that might be affected, a blush is difficult to manufacture on cue, and for this reason became, in the words of literary scholar Mary Ann O’Farrell, “a legible and reliable index of character.”

Eighteenth-century authors expected readers to pick up on this shorthand. A protagonist turning red at a timely moment signaled their refined sensibility and, for women in particular, an innocence about sex. O’Farrell, writing on Pride and Prejudice in her literary study Telling Complexions, says she was “schooled and socialized” by a narrative code that taught her to receive Elizabeth Bennet as the text’s moral heroine. She admits: “I have learned to want from her the blush.” From the time of early fairy tales, literature has relied on the notion of a basic correspondence between appearance and inner nature, if only to trouble it later on. Our anxious investment in this twinning was as true for Austen as it is for a Yahoo! Answers post, dated to this century, with the title: “HELP!! Is there a such thing as a fake blush from a girl?”

Fiction primed me to expect faces I’ve never quite encountered—crimson faces, graying faces, faces stricken and etiolated—as well as sneers and smirks and glowers, expressions for which I have yet to see real-life correlations. Schooled and socialized in narrative code, I, too, have learned to want the blush, most often from my own obdurate body.

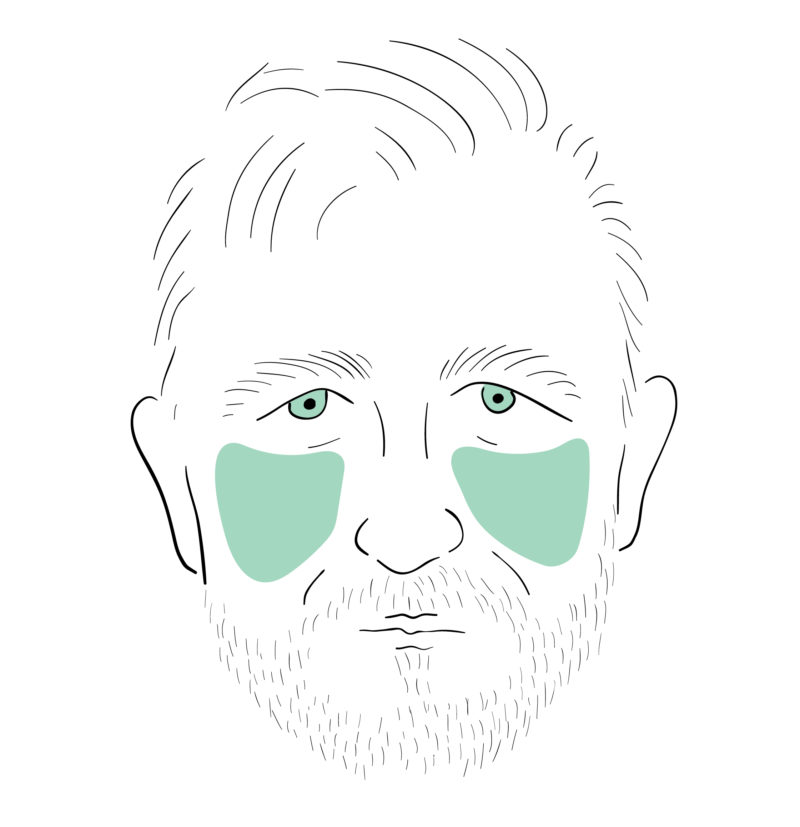

In the early nineteenth century, when dermatology was being institutionalized as a discipline—around the same time, it should be said, that Western imperial activity was strengthening overseas—many physicians in Europe became concerned with the question of whether dark-skinned people could blush. As Sujata Iyengar notes in Shades of Difference: Mythologies of Skin Color in Early Modern England, “Black Ethiopians and tawny Indians were thought to be unable to blush and therefore to experience shame.” If the blush signaled moral refinement, its absence was proof that certain groups did not possess the sensibility necessary for upright conduct or civilization. Mostly, the racist fixation on blushing among thinkers seemed to indicate a failing of aesthetic imagination, which compulsively seized, again and again, on white and red as the central tropic pairing. This myth had seeped in over centuries, abetted—again—by narrative. Shakespeare: “’Tis beauty truly blent, whose red and white / Nature’s own sweet and cunning hand laid on.” Virgil: “When lilies mingled with many roses grow red, such colors did the maiden’s face give forth.”

I do not know what it is to be legible in this way, in fiction or in person. The prized reds and whites of femininity remain inaccessible to me, though perhaps I do not want those as much as something simpler but harder to wrest away, which is space in the text. The blush, like other narrative signifiers of whiteness and white beauty, is a truth universally acknowledged by most works of art. My own skin, however, is mute, unchanging, and unerotic. My fascination with blushing does not seem out of step with ongoing conversations among non-white Americans about the issue of representation, though this term is vague, and I am sometimes suspicious of its designation as a political imperative. I mostly believe that it is an emotional fact, which shouldn’t reduce its urgency, and that people generally want to see themselves reflected in narrative convention because narrative convention is a safe and warm place to be.

Literature resides within an edifice of tropes and writerly tics and gestures, most of which pertain to whiteness. (Note that I am not talking about stereotypes. Note the difference between stereotypes of the Other and mainstays of the unmarked universal, which anyone who has had to read themselves into a canon will recognize immediately.) I know, already, how my body is described in most books, if it appears at all. I know the double meaning in the quip, taken from a nineteenth-century treatise on physiognomy, that “nothing is so detestible [sic] as a woman’s face which is never guilty of a blush.” I know that a simpler, better word for illegible is unread.

In The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, Darwin claims that non-Europeans do indeed blush, providing examples he sourced from a wide network of contacts: missionaries and officials within British imperial holdings who claimed to see, in their colonial subjects, faint signs of flushing. A “Mr. Scott” alleged that Lepcha people in Sikkim, India blushed when he “detected them in a falsehood” or “accused them of ingratitude.” A Chinese laborer was also described as blushing slightly when asked by his white employer “why he had not done his work in better style.” After a certain “Mr. Stack” laughed derisively at the news of a Maori man letting his land to an Englishman, the Maori man, who was present, blushed “up to the roots of his hair.” In all three cases, the body of the Other became legible only once it encountered and acknowledged the reality of white colonial power. It does not seem insignificant to me that on maps from the time, territories of the British Empire were traditionally colored pink.

The joke is that by Darwin’s era, the blush no longer had the currency it had before, when it was taken as an earnest expression of modesty. The spread of cosmetics throughout most levels of European society ensured that women could blush at will, applying to their faces carmine, alabaster, talcum oil, and other pastes in order to evince a plausible flush against a whitened complexion. That carmine was also used as a painting ingredient in portraiture was not lost on social commentators of the time, who wrote ripostes and editorials that attributed women’s “painted faces” to the wicked deception of an artistic hand. Because many ingredients in cosmetics were sourced from the Middle East and Asia, worries circled, like birds overhead, about the consequences of white women entering into intimate contact with foreign substances.

Now bloodless, the blush recurred without meaning even in the forum that had once leveraged it to such effect: the novel. O’Farrell describes how the codification of narrative strategies for the Victorian novel made the blush a rote and unconvincing addendum in romantic prose. No longer exposition, it had become cliché, “debased and robbed of expressivity.” Writers continued to use it, but even they seemed weary of the expression. “Good gracious, look at her blushing again all over her blushes,” one character complains of another in The Age of Innocence, the novel of manners’ best-known hangover. The blush had become cynical. Today, we can digitally enhance the rosiness of our cheeks, and it seems increasingly unlikely that from behind the artifice, curation, and willed affect of the Instagram era, our bodies communicate any truths at all.

Do I still believe in the blush? Even though I cannot blush—even though no one really can? Hand on my heart, I do. I want the blush not because of its beauty or narrative flair, but because it tells us something about ourselves as social beings. An evolutionary reflex, it proves that we are always oriented toward one another, that our bodies know and care whether or not they are being watched.

My favorite old-fashioned trope is the suitor who, seeing the beloved flush with modesty, turns red himself; I like that embarrassment circulates and is liable to move contagiously from face to face, enacting what Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick called the “fantasy of the skin’s being entered.” We blush before death, as Carson writes, because death—like the blush—hints at the dissolution of our physical bounds. Or, per Georges Bataille, “Death opens the way to the denial of our individual lives,” to a future “unconfined within the trammels of separate personalities.” Bataille claims there are primordial channels that run between our varied selves and give us “a feeling of obscenity,” which folds ultimately into the erotic. Mortality is one channel; the blush, another. These channels can never be fully actualized—true and lasting union remains inaccessible to us—but their fictions can still be powerful, especially when they point beyond the tyranny of the individual ego. The blush brings us closer to one another and further from ourselves. It is but a prelude to the hand that, reaching out, touches the cheek of the Other to measure its warmth.