The auditory capacities of teeth may be demonstrated through a simple test. First, find a quiet room to sit in. If you are wearing an analog watch, remove it from your wrist. Open your mouth wide and suspend the timepiece inside your mouth without actually touching your teeth. You will hear a quiet ticking. But close your teeth upon the watch, and you will hear a loud ticking.

This is because you are hearing with your teeth.

The Austro-Germanic Era of Dental Music

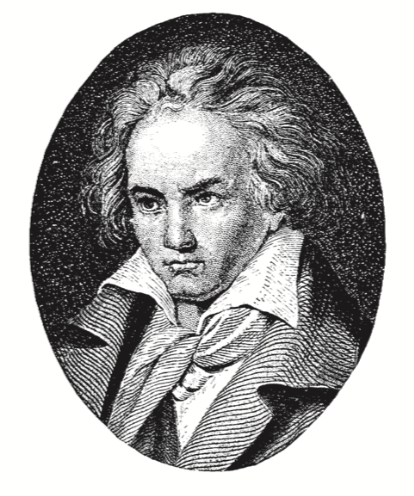

After the onset of hearing loss in 1798, Ludwig van Beethoven listens to his compositions by jamming a wooden rod between his teeth and resting the opposite end on his piano’s soundboard. The concept is known as bone conduction: by passing vibrations through his mandible and into the cochlea, Beethoven circumvented his damaged middle ear and routed sound directly to the inner ear. His method may have been inspired by a 1770 volume by countryman professor Andrew Elias Büchner, author of An Easy and Very Practicable Method to Enable Deaf Persons to Hear. Büchner, in turn, credited the discovery to a deaf merchant in Wesel in 1749. After finding that a tobacco pipe held against a piano soundboard would transmit sound right into a smoker’s head, the merchant also tried capturing sound from the air by clenching a hearing-trumpet in his teeth. This worked poorly; what worked well, however, was biting down on a thin and resonant scrap of wood. Buchner also notes that “the deaf person may hear very well by holding, by the lower rim, a beer-glass to the upper-teeth.”

After the onset of hearing loss in 1798, Ludwig van Beethoven listens to his compositions by jamming a wooden rod between his teeth and resting the opposite end on his piano’s soundboard. The concept is known as bone conduction: by passing vibrations through his mandible and into the cochlea, Beethoven circumvented his damaged middle ear and routed sound directly to the inner ear. His method may have been inspired by a 1770 volume by countryman professor Andrew Elias Büchner, author of An Easy and Very Practicable Method to Enable Deaf Persons to Hear. Büchner, in turn, credited the discovery to a deaf merchant in Wesel in 1749. After finding that a tobacco pipe held against a piano soundboard would transmit sound right into a smoker’s head, the merchant also tried capturing sound from the air by clenching a hearing-trumpet in his teeth. This worked poorly; what worked well, however, was biting down on a thin and resonant scrap of wood. Buchner also notes that “the deaf person may hear very well by holding, by the lower rim, a beer-glass to the upper-teeth.”

The Auditory Teeth Explosion of 1879

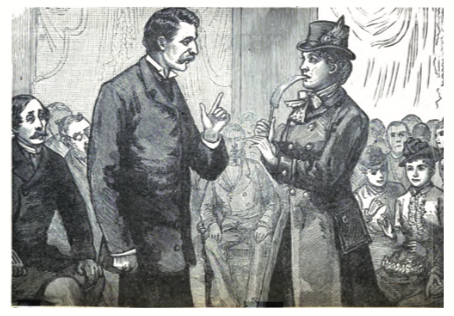

Buchner’s work on bone conduction is revisited by Viennese physician Ádám Politzer in 1864, but little more comes of the idea. Anecdotal usage abounds, however, with one Philadelphia doctor reporting of a deaf patient who bites railroad tracks to hear approaching trains. A more practical approach emerges in the 1870s, when deaf Chicago resident R. S. Rhodes experiments with a vulcanized rubber fan held by a wooden handle and clenched in the user’s mouth. By 1879 mail-order sales take off for Rhodes Audiphones at $10 each (or $15 for a Double Audiphone “for Deaf Mutes, enabling them to hear their own voices”). The invention is lauded in the press with heartwarming scenes of entire classes of deaf children, fans clenched in their mouths, hearing music for the first time.

Wooden rivals immediately follow: the Bostwick Audiphone uses a wooden rod connected to a telephone-style diaphragm, while Fiske’s Dental Attachment for Telephones actually connects a bite-rod directly to a working phone receiver. For those seeking convenience, Graydon’s Dentaphone is a pocket-sized hinged wooden paddle that can be unfolded and bitten to “catch” conversations. (The possibility of catching one’s lips in the hinge is left unaddressed.) There are also cheap imports—but for those who cannot even afford a Japanese Otacoustic Fan, one physician suggests a low-budget alternative: “The voice may be conveyed directly from the skull of the speaker to that of the deaf listener by simply bringing the heads themselves into contact.”

The Electric Denture Revolution

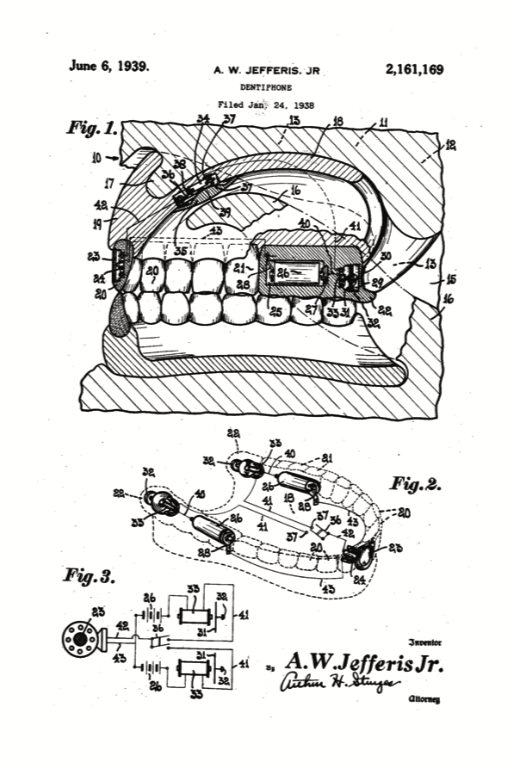

Decades of relative quiet pass after studies show that only one in ten cases of deafness actually benefit from dental audition, as the user must retain the inner-ear capacity to hear their own voice. The popularity of gramophones, however, usher in a renaissance: patents are approved in 1923, 1926, 1927, and 1929 for phonographic biteguard attachments, allowing vibrations to pass from the needle through the tonearm and up into the user’s skull. Several years later, the next logical step occurs: an electrically amplified dentaphone paddle is introduced by Quebec inventor Armand Veilleux. All of these devices required an external apparatus to be operated by the user—a problem leapfrogged in 1938 with patenting of electric dentures. Created by Omaha inventor Albert Jefferis, the dentures hide batteries inside hollowed-out molars, and embed a microphone in the front teeth. This, however, does require that users bare their teeth and smile disconcertingly whenever they want to hear something.

Decades of relative quiet pass after studies show that only one in ten cases of deafness actually benefit from dental audition, as the user must retain the inner-ear capacity to hear their own voice. The popularity of gramophones, however, usher in a renaissance: patents are approved in 1923, 1926, 1927, and 1929 for phonographic biteguard attachments, allowing vibrations to pass from the needle through the tonearm and up into the user’s skull. Several years later, the next logical step occurs: an electrically amplified dentaphone paddle is introduced by Quebec inventor Armand Veilleux. All of these devices required an external apparatus to be operated by the user—a problem leapfrogged in 1938 with patenting of electric dentures. Created by Omaha inventor Albert Jefferis, the dentures hide batteries inside hollowed-out molars, and embed a microphone in the front teeth. This, however, does require that users bare their teeth and smile disconcertingly whenever they want to hear something.

National Osteophonic Malaise

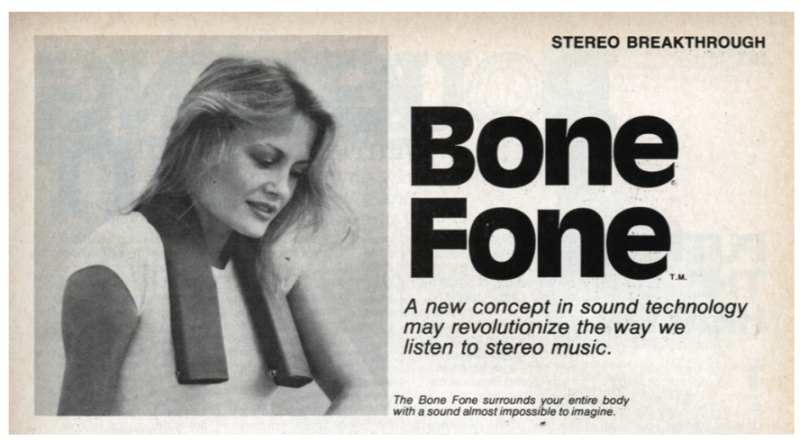

In 1959, Illinois inventor Irwin Cole updates the original dentaphone idea of the eighteenth century by patenting a working tobacco pipe with a microphone embedded in the front of its stem, directly below the bowl, with sound “transmitted through said bit to the teeth of the user.” It does not appear to meet with any further commercial success. Instead, osteophonic listening migrates down to the collarbone, when in 1979 national magazine ads appear for the Bone Fone. “You’re standing in an open field,” their copy begins. “Suddenly there’s music from all directions. Your bones resonate as if you’re listening to beautiful stereo music right in front of a powerful home stereo system.” The product, essentially a Lycra scarf stuffed with five pounds of batteries, radio receivers, and speakers, sells for $69.95 through mail-order outfits DAK and JS&A. The Carter-era Bone Fone ads promise that “now you can listen to beautiful stereo music everywhere—not just in your living room. Imagine walking your dog to beautiful stereo music or roller skating to a strong disco beat.” The device, however, is driven to extinction with the introduction of the Sony Walkman.

In 1959, Illinois inventor Irwin Cole updates the original dentaphone idea of the eighteenth century by patenting a working tobacco pipe with a microphone embedded in the front of its stem, directly below the bowl, with sound “transmitted through said bit to the teeth of the user.” It does not appear to meet with any further commercial success. Instead, osteophonic listening migrates down to the collarbone, when in 1979 national magazine ads appear for the Bone Fone. “You’re standing in an open field,” their copy begins. “Suddenly there’s music from all directions. Your bones resonate as if you’re listening to beautiful stereo music right in front of a powerful home stereo system.” The product, essentially a Lycra scarf stuffed with five pounds of batteries, radio receivers, and speakers, sells for $69.95 through mail-order outfits DAK and JS&A. The Carter-era Bone Fone ads promise that “now you can listen to beautiful stereo music everywhere—not just in your living room. Imagine walking your dog to beautiful stereo music or roller skating to a strong disco beat.” The device, however, is driven to extinction with the introduction of the Sony Walkman.

Millennial Mandibular Sound Transmission

Claiming that “recently, a mechanism for transmitting sound to the ears that bypasses the air and external ears has been determined,” in 2000 a Marin County startup, Sonic Bites, patents a Denta-Mandibular Sound-Transmitting System intended for children’s eating utensils. That same year, Lucent Technologies files a patent for an internal phone headset that operates through a Bluetooth-enabled retainer placed against the roof of the mouth. While wireless spit-covered retainers do not find an immediate market, the concept of Denta-Mandibular Transmission is taken up by Hasbro, which in 2006 releases Tooth Tunes toothbrushes. TV ads promise “a totally turbo tooth experience with music maximized in your mouth…. Boost two minutes of tunes through your teeth and into your head!” Song selections include numbers by Kiss and, disturbingly, Smashmouth.

The Future: Skullphones

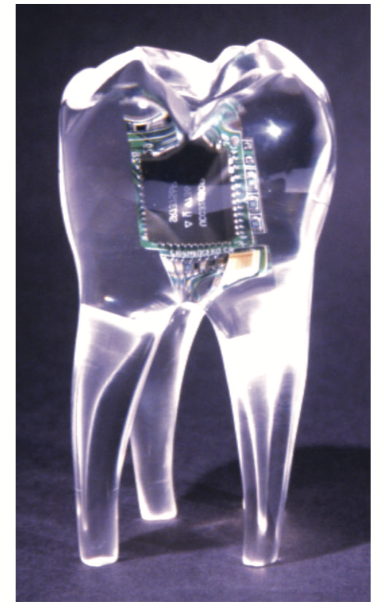

In 2004, Sanyo introduces the first bone-conduction Bluetooth headset, which mounts over the ear without actually blocking it; airport concourses fill with business-class passengers talking schizophrenically into thin air. Two years earlier, however, an even more ambitious prototype was unveiled by two Royal College of Art students: a cell phone surgically implanted in a tooth. The invention was a sensation, receiving worldwide media coverage and making the cover of Time magazine. It was not until April 2006 that Wired magazine discovered that the prototype was a student gag—a Lucite tooth with an old TV-set chip inside. Time had never called to verify the invention, and indeed one hoaxer recalled to Wired that the only person to catch on was a TV cameraman: “He said, ‘You ain’t fucking scientists.’”

In 2004, Sanyo introduces the first bone-conduction Bluetooth headset, which mounts over the ear without actually blocking it; airport concourses fill with business-class passengers talking schizophrenically into thin air. Two years earlier, however, an even more ambitious prototype was unveiled by two Royal College of Art students: a cell phone surgically implanted in a tooth. The invention was a sensation, receiving worldwide media coverage and making the cover of Time magazine. It was not until April 2006 that Wired magazine discovered that the prototype was a student gag—a Lucite tooth with an old TV-set chip inside. Time had never called to verify the invention, and indeed one hoaxer recalled to Wired that the only person to catch on was a TV cameraman: “He said, ‘You ain’t fucking scientists.’”

Their hoax may simply have been ahead of its time, however. Recently, professors Lin Zhong and Michael Lieb-

schner of Rice University proposed using bone conduction as a skeletal intranet for cell phones and medical devices. Binary code transmits across the skeleton with a low error rate and with notably higher security than wireless systems, as hacking in requires physically hugging the user. “People could even swap information between devices through a firm handshake,” New Scientist reports Zhong suggesting. Zhong’s line of research also suggests another possibility for future adolescent orthodontic data transmission: secret communication by kissing and locking your braces.