Scroll

Scroll

Border Acts

June 1st, 2021 | Issue one hundred thirty-six

1.

We were nearing El Paso when my phone rang. We’d been told someone would call with a location, and they did. Off the side of the highway, in a stretch of blight, a rusted shipping container read trump in white ten-foot-tall spray-painted letters. We were just two months away from the 2016 election. The voice on the other end told us to be at a street corner in Juárez at 4:30 p.m. Someone would pick us up.

The car ride was quiet, maybe because we were spooked. Along with the rest of the planet, we’d heard that, not that long ago, Juárez was the most dangerous city in the world. In the days leading up to our departure, I’d cycled through thoughts of calling it all off and then working up the courage not to. I imagined the others, my wife, and our university colleague Dominika, had done the same. I’d clicked through dozens of Mexican and US media stories and images of hyperviolence in the city—mutilated bodies hanging from overpasses, people slumped over in cars riddled with bullet holes, heaps of dead bodies in the middle of the day. All the stories presented Juárez as a charnel house, and the carnage a result of gangland violence rather than of a specific set of economic and geopolitical relations.

The plan was to cross the border at the Paso del Norte International Bridge, and meet someone—we didn’t know who—at the corner of Calle David Herrera Jordan and Rivas Guillén. Our understanding of Safari en Juárez was that it would not take place in a theater but in a variety of places across the colonias of Juárez, including in people’s homes, and that the performance would last approximately four hours. Six locals had each taken in an actor from a local theater company, and they’d lived together for approximately two weeks. They’d opened up their lives to one another and produced a text. Directors were then brought in to develop performances based on the texts. These were rehearsed, and then a run was announced.

It was four o’clock when we pulled in to a parking lot directly across from a pedestrian bridge at the US–Mexico border. As we paid the parking attendant—a spindly old man wearing a white tank top and pleated dress slacks—I remembered that the area around the bridge was where a Border Patrol agent named Jesus Mesa Jr. had shot and killed an unarmed fifteen-year-old boy named Sergio Adrián Hernández Güereca in the summer of 2010. I remembered that, on and around the day of the shooting, news reports had prominently featured information from official sources—a spokesperson for the FBI told the El Paso Times that the agent had shot the teen after a group of Mexican nationals “surrounded the agent and threw rocks at him.” The Associated Press reported on the boy’s alleged ties to illegal smuggling, and The New York Times ran a story that ended with two paragraphs about the supposed danger and seriousness of “rock attacks.” But cell phone video emerged of a scene that, to me, very clearly looked like a Border Patrol agent—who was not surrounded—executing a fleeing boy who’d stopped to look back at his captured friend. In 2012, at the conclusion of its investigation, the Justice Department reported what it saw: “insufficient evidence to pursue federal criminal charges.” And in February 2020, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that the Border Patrol could not be sued for the boy’s killing.

Halfway across the bridge, I stopped to look down for any visible sign of where the shooting had occurred, but saw only white graffiti on a concrete embankment that read berlin wall. There was chain-link fencing everywhere, and it felt very much like an open-air prison, not a bridge, which is usually a place of connection and exchange. This was all part of an apparatus of immiseration and ultimately death—something that would become brutally obvious in the next few years, when the Trump administration would refine an already abysmal asylum process in response to the migrant caravans. Asylum seekers attempting to present themselves to authorities would be turned away and left marooned in the limbo created by US law and neo-imperialist policies toward Latin America. Many of them would sleep at the bridge’s base, waiting months before they were able to be considered, only to be denied and turned away.

There were three or four people already gathered on the street corner when we arrived. We exchanged cursory greetings, and more people came every few minutes. Around the corner, a pack of black motorcycles cracked thick concussions into the air. Some of the bikers, a motley crew of men and women wearing black vests, sat on their bikes, while others smoked under a tree, and a few bought esquites from a street vendor. It soon became clear that all the others on the corner—except for a couple that lived in El Paso but were originally from Juárez—were locals. One guy was a professor at a nearby university, and an older woman, who’d come alone, was a homemaker. There was an art teacher and her husband, a salesman, two crew guys with clipboards, and us. Conversation was light, but there was a serious undercurrent that kept things from becoming too cheery, and brought to the chitchat a muted, discordant note. Most of them had lived through Juárez’s transformation into a city of foreign-owned assembly lines and a theater of the drug war. They’d lived through the local and federal governments’ capitulations to the maquiladora sector, and their collaborative wringing of optimal conditions from the city and its people, led by companies like North American Production Sharing Inc., or NAPS.

Headquartered at the end of a luxury shopping promenade in the wealthy coastal city of Solana Beach, California, NAPS hardly attempts to hide what it’s doing. It bills itself explicitly as a company that helps manufacturers “offshore.” On its website, one tab reads, “Why manufacture in Mexico?” The copy explains, “It all starts with the low cost of well-trained labor”—labor that is, “relative to the United States, and most other developed countries… approximately seventy percent less expensive.” The “NAPS operating model” capitalizes on NAFTA and “over forty-four other trade agreements” put in place by the Mexican government.

Approximately 85 percent of NAPS’s client base chooses to expand to Mexico “under shelter,” which means they operate under a Mexican corporation owned by NAPS. Because these foreign companies have no legal presence in Mexico, they avoid any liability associated with doing business there but still benefit from all government tax and duty-abatement programs. Below is a list of advantages NAPS claims are associated with operating under a Mexico shelter corporation.

- No Legal Liability in Mexico

- Reduce Labor Costs

- Payroll and Benefits Management

- Economies of Scale

- Labor Flexibility (Seasonality)

- Quicker Start-Up

- Immediate Access to Special Corporate Certifications (If Needed)

The low cost of labor is something NAPS both takes advantage of and helps produce, and it is, in fact, so low that a worker making the minimum wage during the Peña Nieto years was able to afford only 33 percent of the “Recommended Nutritional Basket,” an official metric recognized by the Mexican government that amounts to a collection of foods that represent the bare minimum necessary to sustain life. The metric once included other necessities like housing, provisions for cultural participation, and education, but after the liberalization of the Mexican economy in the 1980s—instituted by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, and precipitated by a global economic crisis and the predatory lending schemes of US and other Western commercial banks—these items were separated into their own indexes, which allowed many policymakers to regard them as inessential. In effect, the basket was stripped of the things necessary for life and left with only those necessary for bare survival.

At around 4:45, a pickup truck pulled up beside the ice cream shop across the street. Two crew guys with clipboards directed us into the bed of the pickup. We packed in and took off, winding through small streets lined with shops before pulling onto a main thoroughfare. My legs were pressed up against the salesman’s. Everyone was bouncing off one another, but no one said anything until the salesman motioned at a few nondescript buildings. “There,” he yelled over the speeding traffic, “is the neighborhood where I grew up.” A few seconds later, he signaled toward a large house. “And that,” he said,“was where Juan Gabriel’s mother worked as a cleaning lady.” He paused. “When Juanga struck it rich, he bought it for her.”

The truck banked a turn and lurched down a ramp into a broad concrete spillway. Buses zoomed by, their tires kicking up droplets of what was likely black water. Parts of the spillway were contained by walls covered in graffiti that ranged in skill and the level of duress under which it was painted. I’d always been interested in graffiti because I’d known a few writers growing up in Chicago, and from what I’d observed, it was an obsession. It seemed to arise from a profound sense of alienation, and it required the willingness to break and enter, trespass, be beaten or killed by the police, or otherwise die. And since the city of Chicago usually painted over throw-ups within a day or two, the truly dedicated enacted this willingness on a nightly basis. It was a transgressive art form that required no institutionalized training and, from what I’d seen, was practiced almost exclusively by those from the underclass. One piece on the spillway wall was a bubble-letter throw-up that looked especially rushed but nevertheless suggested a high level of skill. The letters were filled in by broad lateral sprays of white paint with some space between the strokes. They were outlined in red lines that were fatter and lighter in color where the writer had been reaching—except for the last letter, which was only the amorphous white fill and therefore remained indiscernible. I wondered what had caused the painter to run off, leaving his piece incomplete—what kind of willingness was required here in Juárez to make those letters.

We exited the spillway into a residential area with small houses that were made mostly of painted concrete and corrugated tin. Many of the streets were paved, at least partially. One of the others said we were in a southwestern colonia. The truck parked on a quiet block lined with houses and near a park. The crew guys directed us toward a two-story home with a white metal gate. A small woman in her fifties wearing a house apron welcomed us onto her home’s shaded side patio. An old skinny man in a cap leaned on the rail of the home’s second-story balcony, squinting down at us. A half dozen kittens slunk in and out of a tarp covering piles of construction debris. At the far end of the patio, painted onto the outside wall of an adjacent building, a black-and-white Jesus cast his gaze into the pale blue sky.

The woman led us into her house through a small, modest kitchen, where another woman rinsed something in a plastic colander. We walked into a dim, narrow room, squeezing between a wall and a teenage girl, who stood behind a folding chair clutching a seated boy’s shoulders, both of them staring into an illuminated computer screen. The final room was lined with short stools along two walls. There was an unmade bed in a corner, a drum set, and a large, incomplete rendition of The Creation of Adam painted directly onto the ceiling. A couple of us sat on the stools, and the others piled onto the unmade bed. The woman who’d been in the kitchen walked in with a plastic basin full of Styrofoam bowls of soup and passed them out. The hot liquid tasted like a simple broth my mom used to make when I was a kid—water boiled with a halved onion, a few crushed garlic cloves, and some blended tomatoes—and contained mixed beans and cut-up hot dogs. When you are invited to eat in someone’s home, often the host cooks something out of the ordinary, meant to impress, but this was the kind of meal our host might have made with things she had on hand, perhaps something she’d eat for lunch on any given day.

One of the crew handed out beer cans with the tops cut off and filled them from caguamas he retrieved from a cooler. For a few minutes, we all ate and drank, and I noticed the fear I’d been feeling out in the street was gone. Everyone was chatting, joking, and the caginess that had pervaded our interactions dissipated. Just as people were putting down their bowls, two men stomped into the room wearing only boxer briefs. The shorter and darker of the two, who we’d later learn was named Julián, opened a stepladder and climbed to the top. He grabbed a palette, dabbed at small mounds of paint, and then at the painting of God on the ceiling. The other nearly naked man, Alan, was one of the two crew guys who’d picked us up earlier. He told us we were in Julián’s home, where he lived with his mother, the woman who’d greeted us at the gate. The men began to speak the text they’d produced together, which had the quality of an impassioned late-night conversation. As he blotted paint on the figure of Adam, Julián told us that as a kid he’d gotten into graffiti and murals, that it had allowed him to move throughout different parts of the city that are usually segmented by closely held affiliations. People with different affiliations hired him to paint things they wanted to be visible, so he did. But he also painted his own stuff most days—a practice he had cultivated. It was time alone, usually under the anonymity of night, that belonged only to him, and that wasn’t dictated by a boss or the strictures of the city.

Julián traced the room, walking inches from us, while staring into our faces. The veins in the whites of his eyes were visible to us, as ours were to him. I could smell his breath and feel the heat emanating from his body as he leaned in. It occurred to me that what both men were saying and doing was predetermined, as most conventional theater is, but they were also playing themselves. I wondered if their performance was closer to that of fictional theater, or to the predetermination we enact in most of our daily speech and movement. The script, after all, carried their experience, as they understood it and as they’d chosen to show it to us. There was no stage, which meant the lines between performers, play, and audience weren’t static or preestablished but left to us to draw. This made it feel less like watching something external and more like being in a confrontation with someone, an “other,” who, unlike a character in a play, contained a world of their own, one that extended beyond the boundaries of the performance. All this produced the sense of being implicated.

Alan began aggressively dressing himself in a button-up shirt, slacks, and a jacket. He told us he’d been going to school in order to break into the professional class to appease his family, but that his real passion was theater. Julián helped tighten his tie, and as he did, Alan told him he felt unable to tell his family who he really was. Gradually, he revealed that he was referring not only to theater, but also to his sexuality—that he was gay. He communicated the steep cost of hiding those aspects of himself from the people who were supposed to be a source of unconditional love. As he did, his eyes welled up, but I could sense a quality in his behavior that was absent from Julián’s, something like a residue of acting that I can describe only as akin to telegraphing a punch, which usually manifests as an unconscious and almost imperceptible physical tell—the loading of weight onto the front foot, for example—that reflects a mental process. It was almost as if Alan, despite playing himself, couldn’t help but run his own experience through his training as an actor.

Across the room, Julián, the non-actor, sat down at the drum set and began riffing as he commiserated with Alan’s revelation. At first, he beat the drum slowly and quietly as he found his groove. A few times, he slammed down the sticks, stood, and paced the room. Then he would sit again and commence beating the drum more violently. In fragments, Julián started telling us a story, yelling over the drumming. He told us he had a child, and that something new had grown inside him when he felt his baby’s weight for the first time. He slammed the sticks down and paced, his body becoming a collection of knots, and when he came back, he said he had been offered money to carry a bag from place to place. Because of that, he’d spent a year in jail. He didn’t have to say it: it was clear to me, as I suspect it was to others who’d grown up with some level of deprivation, that his decision to accept the offer had come, at least in part, from loving his child.

By the time Julián revealed that he’d been a small, disposable part of the drug trade, we’d already eaten his mother’s soup, inhaled his smell from his bedsheets, seen his almost-naked body, and felt the depth of his love as a father. It wasn’t so easy to draw the usual lines. His person cut against the official narratives that the intense violence of the drug war was visited upon and perpetuated by criminals who were categorically different and distinguishable from us, the innocent; that those who suffered this violence had it coming; and that the best rubric through which to understand all of it is crime—the illegal actions of individuals, or groups, predicated on bad choices, that call for extermination by the police. He reminded me of so many of my childhood friends, kids whom I shared popsicles with in the summer, whose mothers I knew, who would go on to take up the place society had made for them.

Before, when he’d been riffing, Julián’s emotions came through in the varying force with which he’d hit the drums. But now all his strikes came as hard and fast as his arms could muster. Now his violence and anger rattled the windows, climbing and climbing until, at the moment the drumbeats reached an unbearable peak, he threw the sticks to the ground and stood, panting. What would have been an abrupt silence was filled with ringing. He scanned the faces in his room and told us his daughter had died.

Low in the sky, the sun drove through the windows in columns of light. For a moment, all I could do was stare into it. Then someone, I don’t remember who, took us away, led us out to the side patio. I felt I was not in control of my movements, as though I were being pulled along by a magnet, and as I passed the threshold of the home, something ruptured. It seemed like maybe others felt this, too, because as we left, several people started crying. I couldn’t stop thinking that Julián had been locked up for what must have been the majority of his baby’s life. Everything cast a long shadow the color of a deep bruise.

The two men emerged from the house and led us out into the street, where the same fleet of rumbling black motorcycles idled. Down the block, a white car suddenly appeared, sped toward us, then screeched to a stop. The driver, a young guy, burst out with something in his hand, charging at Julián, whose back was turned. The guy swung the object, a bottle, at Julián’s head; Julián somehow managed to duck. The bottle shattered, and all at once a scrum erupted. We were shoved onto the backs of the motorcycles by the crew, and before I knew what was happening, I was clutching a burly stranger as we tore uphill, away from the melee. It would be a long time before I’d discover that the fight we’d witnessed had also been witnessed by other groups on other days of the performance.

We were dropped off at a park with a small soccer pitch and basketball courts, where several dozen kids of all ages ran around laughing and playing. It was impossible to reconcile this scene with the reality that six years ago, in 2010, violence peaked, with almost 3,700 homicides occurring throughout the city, but there we were. Julián appeared in a far corner of the park and waved us over. His face was painted white, and he lit a small torch. He took a swig of liquid from a bottle and sprayed it through the flame into the air, producing a huge orange plume. Another young man appeared holding metal orbs on chains. He passed them over the torch, which lit something in their centers. He held the ends of the chains while swinging them violently, making impressive trails of fire in the diminishing sunlight. It was a variation of a show I’d seen in many urban centers throughout the so-called developing world. I’d seen it in Veracruz, and also in Manila. Even more striking to consider than the identical aesthetic dimensions, was the reality that the places were all formerly colonized countries that had then been dominated economically and militarily by the West. They were places that lived, today, with some of the world’s most severe inequality. The performers came from the swaths of racialized working-age people for whom there was no place in the domestic labor markets and global economy. They fought for survival by selling, to tourists from the West, a sense of awe they could generate with their ingenuity and next to nothing. When Julián breathed fire into the evening’s darkness, the plume made the sound of a barreling train.

2.

With one hand white-knuckling a bus seat, and the other wrapped around a microphone, the man in the aisle said he was a historian at the city university. Over his shoulder, hand-painted directly onto the metal sheeting of the bus, were the words la bella y la bestia (beauty and the beast). He launched into a five-minute description of political economy that spanned more than fifty years. It was wholly inadequate, but at the same time necessary, and depicted a world beyond what most bourgeois US artworks, even those that grapple with injustice, allow for. In the US, when the voices of the oppressed are allowed onto even modest platforms, it’s almost always in the form of commodified narratives of dramatized suffering, which come at the exclusion of any concrete, precise, critical analysis of the structures that order our social reality. Here, the historian was attempting to contextualize what we had just witnessed in order to create the kind of dimension that would allow us to think about and feel how the individual tragedies and joys of life are never separate from the social realities from which they arise and upon which they play out.

He began his narrative in 1942 with the Bracero Program, a set of agreements that institutionalized the practice of Mexican laborers going to work in certain US sectors on a temporary basis. Millions participated, and the program was largely billed as necessary because of US labor shortages during World War II, but historians have cast doubt on the scale and veracity of those shortages. Many alternative explanations for the lack of available labor have been offered, like the flight of US workers from horrendous jobs in agriculture to higher-paying jobs in the war effort, knowing they could rely on support from welfare programs initiated during the New Deal. There are examples of the worker shortages being exaggerated or outright fabricated in California and Texas. In his book Agrarianism and Nationalism: Mexico and the Bracero Program, David Lessard writes: “Investigations by the War Food Administration and the War Manpower Commission showed that there actually was no labor shortage in Texas in 1943. Both agencies were convinced that Texas growers wanted to flood the labor market with Mexican workers to maintain low wages.” Alongside the Braceros, uncontracted Mexican laborers continued to migrate to the US for work. The program was extended until 1964, perhaps because, in addition to ameliorating legitimate labor shortages, it allowed US growers to subvert the intensifying efforts of US trade unionists by strengthening growers’ control over a hyper-exploitable, contingent labor supply. The Braceros themselves suffered horrific working conditions; the destruction of their families; government and employer surveillance; and racialized violence. When the program ended and the workers were repatriated to Mexico, the 10 percent of their checks they’d been paying into retirement accounts kept by the Mexican government disappeared.

Toward the end of the Bracero Program, the population in Mexican border cities exploded. Juárez’s population grew from 48,881 in 1940 to 424,135 in 1970, the highest rate of growth in its history, occurring in large part because of repatriating Mexican laborers. As historian Lawrence Douglas Taylor Hansen has noted, this mass influx also resulted in about half the population being unemployed. Many of the people who settled in Juárez had been part of the rural working poor. They were drawn into and preyed upon by the US, after having been failed by a Mexican state, and economy, that was itself at times coerced by the US, and at times complicit in its neocolonial ambitions. In 1965, Mexico’s policy response was to join the emerging global trend of “production sharing,” which consists of companies breaking up manufacturing operations and locating the components in countries with the most favorable conditions for generating profit. Under the Border Industrialization Program, Juárez became a city of assembly lines, or maquiladoras—facilities where duty-free components are imported, assembled, and then exported to be sold in the United States. Moving US assembly across the border meant tapping into a labor force that could be paid a fraction of what workers in the US would accept, while keeping ownership and research and development elsewhere.

By the end of the 1960s, despite the huge influx of returning male Braceros, the majority of maquiladora employees were young women. According to reporting done in the ’90s by Debbie Nathan, maquiladora managers, most of whom are men, believed women workers “have more nimble fingers, deal better with boredom, and are ‘more docile’—i.e., less inclined to engage in disruptive behavior including union organizing.” This kind of logic goes all the way to the top. In 1971, US beltway scholar Donald W. Baerresen authored a book titled The Border Industrialization Program of Mexico, described in The International Executive (a now-defunct journal of business, political science, and international relations) as “written mainly as a guide for firms in setting up plants in Mexico’s northern border region and for governmental thinking about the program.” The book provides “information designed to help companies pick the best location for factories,” like wage and unemployment differentials by precise locality, so that, for example, garment industrialists in Los Angeles could see that, rather than set up an operation in Baja California, they should go a bit farther south to Sonora, where “labor costs are about 25% less.” In addition to this economic data, the book includes intelligence on “other factors useful in determining optimum locations.” Baerresen writes that “it is often the daughter working in an industrial plant who becomes the main source of family income. Some families are supported almost entirely by the income of such a daughter. When the father does work, it happens not infrequently that the daughter earns more.… Loss of a woman’s factory job can represent a serious financial blow to her family. Thus we find that the members of a worker’s family cooperate to ensure that she performs properly.”

Mexico’s place in the global economic order meant that US companies could count on the border zone embarking on a decades-long competition with other poor localities to do whatever it took to keep operations there: eliminating duties, slashing tariffs, degrading worker protections, skirting environmental laws and standards, creating loopholes to circumvent the Mexican constitution’s restrictions on direct foreign ownership, and stratifying labor by any means available, like marshaling misogyny and racism—in other words, creating the conditions under which violence, human degradation, and misery become endemic.

Molly Molloy, a research librarian and chronicler of border issues, and Julián Cardona, a former Juárez maquiladora worker turned photojournalist, worked out a rough comparison between the “economic activity generated by wages in the maquiladora sector” and earnings made in the city’s illicit drug market. They concluded that “on average, maquila workers in Juárez earn the lowest salaries in the industry and 90% of the employees in this sector in Juárez are line workers—the lowest paid of all maquiladora jobs,” and that “the domestic drug market in Juárez generates about 85% of that generated by the maquiladora industry, which is by far the largest employer in the city.”

3.

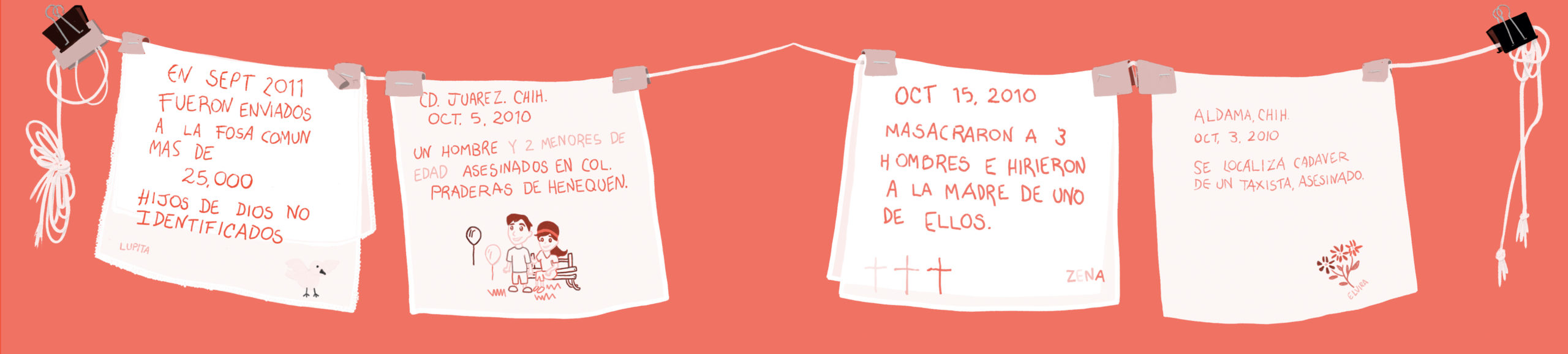

EN SEPT 2011 FUERON ENVIADOS A LA FOSA COMUN MAS DE 25,000 HIJOS DE DIOS NO IDENTIFICADOS LUPITA (IN SEPT 2011 OVER 25,000 UNIDENTIFIED CHILDREN OF GOD WERE SENT TO MASS GRAVES LUPITA)

(Small white dove in the bottom right corner.)

CD. JUÁREZ, CHIH. OCT. 5 2010, UN HOMBRE Y 2 MENORES DE EDAD ASESINADOS EN COL. PRADERAS DE HENEQUEN MAGDA (CD. JUÁREZ, CHIH. OCT. 5 2010 ONE MAN AND TWO MINORS MURDERED IN PRADERAS DE HENEQUEN MAGDA)

(Along the bottom, two cartoon figures sitting on a bench. One presents as a man, the other as a woman. Two balloons float nearby.)

MASACARON A 3 HOMBRES E HIRIERON A LA MADRE DE UNO DE ELLOS ZENA (3 MEN WERE MASSACRED AND THE MOTHER OF ONE OF THEM WAS INJURED ZENA)

(Along the bottom, three crosses made simply of two intersecting lines—one yellow, one blue, one green.)

ALDAMA, CHIH. OCT, 3, 2010, SE LOCALIZA CADAVER DE UN TAXISTA, ASESINADO ELVIRA (ALDAMA, CHIH. OCT, 3, 2010, LOCATED: THE BODY OF A MURDERED TAXI DRIVER ELVIRA)

(Green stem that branches into three flowers: one purple, one fuchsia, one orange.)

CD. JUÁREZ, CHIH. OCT. 11, 2010, UNA PAREJA FUE ACRIBILLADA CUANDO ARRIBABA A CENTRO COMERCIAL (CD. JUÁREZ, CHIH. OCT. 11, 2010, A COUPLE WAS RIDDLED WITH BULLETS AS THEY ARRIVED AT THE MALL)

(No signature line. No image.)

The messages were strung together and arranged into a kind of tunnel on a sidewalk bordering a community center in a residential neighborhood. One side of the string was attached to a chain-link fence topped with barbed wire, and the other to a series of metal poles sticking out of buckets filled with rocks. This is where we were let off the bus. Looming overhead, a hillside was painted with the command cd juárez la biblia es la verdad leala (the Bible is the truth, read it). The sun, no longer visible, slumped behind the hill, casting a pale gray light onto the neighborhood.

When I entered the tunnel, I had no idea what it was. The extreme dissonance of cartoon animals sewn in colorful yarn, accompanied by truncated descriptions of people’s violent deaths and anonymous mass interments, sunk me into a deep gloom. Each message was stitched onto a kerchief, in idiosyncratic lettering that communicated a human touch, even though the messages themselves were composed in the sterile language of sound-bites or a police blotter. I imagined someone sitting and stitching them, taking a source material meant to transmit information in a way that launders reality, annihilates what it’s really saying, and revivifying it. The process of stitching itself prolonged the way the words were experienced. And stitching the words onto a quotidian object like a kerchief somehow estranged them, once again making their horror, and the horror of their naturalization, visceral.

We exited the tunnel and emerged into a three-way intersection abutted by a huge mural. Its background was painted to look like a cloudy blue sky, and in the foreground it featured the faces of eighteen young women, rendered in black and white. In the center, the face of a nineteenth woman was painted within a heart-shaped rosary and flanked by an angel and the Virgin of Guadalupe. Before I could put the images together, a crew person said the mural was a tribute to women from the area who’d been murdered and/or disappeared—victims of what’s come to be known as femicide.

We were led to the door of a community center, where we pushed past a heavy curtain into pitch black. As I entered, an unseen hand grasped mine, guided me into the darkness, then lowered me into a supine position on the floor. The room, which I could tell was large, was silent except for the faint shuffling of the others being guided into the space. After a few moments, I could hear gentle breathing as someone lay next to me. A bright video image suddenly appeared on the wall. In it, a young girl, maybe eight or nine, had her hands raised above her head, and her voice cut through the room: “Nadie puede encontrar a mi hermana, pero yo sí.” (“No one can find my sister, but I can.”) Her face was covered by a T-shirt that read i ♥ the beatles. She uncovered her face and walked over to a framed poster of the Virgin of Guadalupe. Two photographs of a teenage girl were wedged into the bottom corners of the poster’s frame. She pointed at them, smiling. For the rest of the short video, the girl jumped on a bed and moved throughout her small home, retrieving photos of her sister from various places. She told the camera repeatedly that they were of her sister, Jocelyn. The last photo she held up was of a baby sleeping on a blue knit blanket with one fist clenched above its head, its eyes pressed closed. “Mi hermana, Jocelyn.”

Amnesty International puts the number of women killed in Ciudad Juárez and the city of Chihuahua between 1993 and 2005 at 370. The exact number is contested, but most reliable sources indicate that it began to rise precipitously after 2005. Working women, scholars, and organizations began mobilizing. For years, the national and international media mostly ignored them. When they finally did begin to take notice, it was to focus on the most brutal cases, in which women were sexually violated, murdered, and mutilated by assailants unknown to them. Sensationalized stories parroted wild speculations about the possible culprits—serial killers, bands of murderous bus drivers, and cartel snuff film producers—while ignoring the more horrifically mundane cases in which the women were subjected to domestic violence or killed by members of their families, communities, or workplaces. The term femicide, or “the misogynous killing of women by men,” popularized by feminist author Diana E. H. Russell in the early ’90s, gained traction globally. In Juárez, the groups working to eradicate femicide were also engaged in a movement to conceptualize it concretely. Many understood that the stakes of both of these struggles were life and death, because the application of different conceptual frameworks would result in radically different prescriptions. It mattered whether this violence was understood as the work of monstrous, pathological, and therefore easily circumscribed “others,” or by more ordinary men; whether police impunity was the terminal point of the analysis or one vector in the horrible matrix of power relations in this export processing zone; whether the analysis would center on the actions of granular individuals or whether each person’s actions would be contextualized by the social, economic, political, historical, and cultural factors that determine so much of how we live and how we die.

The room went black again. I could sense movement to my left, and then a gentle breath on my head and neck. The darkness was so absolute that our eyes swelled with shifting splashes of light. After a few moments, a man began to speak softly into my ear. His words were gentle but labored, as though they were being pulled by something anchored deep within his core. In a few sentences, he told me the story of a world obliterated, a daughter who left one regular morning and never came home—his voice breaking against his teeth. And then he whispered her first name into my ear and told me to carry it with me everywhere.

4.

On September 30, 1994, a seventeen-page ad paid for by the Mexican government was published in USA Today. It read, in part, “The opening of the Mexican economy has turned the country into one of the main destinations for investment around the world, one of the best [US] commercial partners and one of the most appreciated stock issuers within the international value markets.” Nine months earlier, on January 1, a plurality of Mayan Indigenous groups and their allies declared war against the Mexican state. The same policies that had made Mexico such an ideal commercial partner, valued stock issuer, and site for foreign investment had also, predictably, immiserated vast swaths of the Mexican population, affecting Indigenous communities most brutally. The chasm between rich and poor was so extreme, the piece in USA Today admitted as much: “the benefits are yet to be distributed evenly across Mexican society…. The number of citizens living below the poverty line… increased from 13 million in 1990 to 24 million in 1994.” A Washington Post article, also from 1994, titled “Mexico’s Billionaire Boom,” outlined how “during the Salinas regime [1988–1994], 24 individuals or families landed on the list of the world’s billionaires published by Forbes magazine in July, and at least four more billionaires have been identified since then. In 1991 Mexico had just two billionaires.” By 2016, 71.9 percent of Indigenous people, or 8.3 million, lived in poverty, with three out of ten living in poverty so extreme they “presented three or more social deprivations,” as measured by the National Council for the Evaluation of Social Development Policy, and lacked the “capacity to acquire the basic food basket.”

From the community center, we walked into a hillside neighborhood with unpaved streets and houses made of repurposed scraps. A few mangy dogs tore at food in a pit. The sky was the color of a ripe plum. We turned onto a steep grade partially lined with hexagonal pavers and a few stretches of stairs, one made of concrete, others of scrap wood. Fenced-off parcels contained houses; one was nothing more than a few pallets hammered together and topped with plastic sheeting, while others were made of cinder blocks and corrugated tin. One had a large brick-and-rebar planter from which sprung an unruly white oleander that looked like an exploding firework.

We were invited into one of the homes by a middle-aged woman in blue scrubs. Inside, chairs were pushed along the wall of a small room that must have served as a living and dining area, kitchen, and perhaps even a bedroom. A stove and some cabinets lined the opposite wall, and an old fridge was tucked into a corner. At the center was a table with a peculiar wooden box on it. Looking over the rim of her glasses, the woman introduced herself as Lidia and motioned for us to sit. Another woman, perhaps in her early twenties, passed out cups and tortas made of pickled pork skin and chiles in vinegar. Lidia began telling us about her work at a community center as she poured soda for us. She said what we were eating was one of her comfort foods, something she desperately needed during her lunch breaks. The rest of her day was spent trying to figure out ways to alleviate the suffering of the women who came to see her, women who suffered the brunt of multiple kinds of violence and upon whose backs someone else’s prosperity was built.

The younger woman, Claudia, stood at the screen door and looked out toward a cluster of homes across a dirt lot. Lidia asked her what sickness she thought was ailing Juárez. Claudia turned to her but remained silent. Lidia then walked to the door and motioned outside. “Juárez is sick with death—death and impunity,” she said. She told Claudia that even though death hadn’t reached her yet, it was getting close; it had reached people she knew. She motioned with her head toward a house on the hillside about a hundred yards from where we sat, and said that the neighbor’s son and husband had been killed, despite their not being “involved” in the drug trade.

According to a Mexican government database, 34,162 people were massacred in drug war killings between December 2006 and December 2010. Of those, 6,437 were killed in Juárez. The numbers are, in all likelihood, much higher. As feminist scholar Melissa W. Wright notes, almost two decades after the city gained “infamy as a place of femicide,” its reputation shifted to “a place of unprecedented drug violence.” Among the many differences between these forms of brutality, Wright noticed some essential similarities: the brutalized all came “from the city’s working poor, whose productive labor established Ciudad Juárez’s reputation as a profitable hub of global industrialization in the era of the North American Free Trade Agreement”; and both femicide and drug violence relied on gendered stories to explain away the responsibility of the states and multinational corporations for the bloodshed. In the ’90s, the ruling class of Juárez took advantage of a long-standing cultural antipathy toward women who stray from the domestic sphere to blame murdered women for their own killings. Similarly, the violence of the drug trade was rewritten as a story about rational businessmen engaged in a competition appropriate for their illicit economy. The government alleged that the escalating violence had an internal coherence, that regular people had nothing to worry about, because those who were massacred were criminals killed by other criminals. At first, this story was used to justify the government’s inaction, but after former Mexican president Felipe Calderón’s 2006 escalation of the war on drugs, it was redeployed to maintain support for a drug war that had only intensified the carnage, and for a military that was accused of human rights violations. When the government numbers were released, the Calderón administration portrayed the violence as not only contained among criminals, but also as geographically isolated, claiming that “in 2010, out of all the homicides linked to organized crime, half of them took place in only three states: Chihuahua, Sinaloa and Tamaulipas.”

But the numbers are almost certainly wrong, and depending on the methods used, tell any manner of different stories. The underreporting of crime is rampant, but even more than that, the criteria and circumstances by which someone’s death counts or doesn’t count as drug-war-related are arbitrary. Molloy has kept her own detailed accounting of violence in the border region and beyond. Though her tally of the dead is much higher, she observes that “while there is a lot of criminal-on-criminal killing, a lot of people are getting killed by paramilitaries, death squads and security forces.” Like Wright, Molloy observes that, by and large, it is the poor who are killed, and that “most of the victims are ordinary people, exhibiting nothing to indicate they are employed in the lucrative drug business.” While this is necessary to point out in order to counteract the official government story about who’s doing all the dying and who’s doing all the killing, it’s also important to face the reality that it is people—in all their ordinariness—who become involved in the drug trade.

Claudia thrust a photo into my hand—it appeared to be her family’s. It was nondescript: an older photo, maybe from the ’70s, of a young man standing beside a truck. The way he smiled suggested something exciting had just happened, or perhaps an electricity between himself and the photographer. As we looked at the photos, Claudia paced and told us about her childhood, about her strained relationship with her father. She managed to suggest a deep injury their relationship had suffered without telling us very much about it. At one point, her pacing abruptly stopped and she sat at my feet and clutched my hand. She began speaking to me as though I were her father, perhaps telling me all the things she wasn’t able to tell him, and before long she was overtaken by grief. She stood, collapsed into my lap, and wept. She was small, but the weight of her person felt immovable, like a cistern full of water. She broke a tension I hadn’t sensed accumulating all afternoon. I found myself weeping, too, at her grief, but more so at the sum of it all. When I looked around the room, the others were weeping too.

Lidia walked to the table and opened the small wooden box. It was full of tiny glass bottles that contained the essences of desert plants, whose properties she used to offer some degree of healing to the women who came to her in pain. “Desert people are cured with desert flowers,” she said. Her words reminded me of a moment I’d had a few years back in a saddle between mountains in the Sonoran Desert. I’d seen a lone purple flower the size of a grain of sea salt emerging from between two stones. I reasoned that the austerity of the landscape accounted for its size and loneliness, that nothing much could survive such harsh conditions, but when I stood and looked out into the valley, I saw waves of purple in all directions, spilling over the horizon.

By the time we left Lidia’s home, the streets were dark. As we wound back to the bus, the crew members shone flashlights on the uneven ground, creating a chaos of images in shaking triangles of light. A dog’s bark threaded itself between the houses in the valley. My mind tried to hold things together, but couldn’t. On La Bestia, the night rushed in through the open window. A few minutes into the ride, colored lights strobed against buildings in the distance. My first thought was that we were approaching the aftermath of some violent incident, but music, at first distant and indiscernible, swelled as we arrived. The bus deposited us into a crowd of several hundred people, many dancing to a live band, others clustered up and down the block, and several dozen lined up at a few plastic tables, where women were making plates of food. The night would end with a party. I pushed through sweaty bodies until I came upon Julián, who looked dazed. He was smoking a cigarette and drinking a large beer. We shook hands and bumped shoulders in greeting. He took hard drags from his cigarette, like he was trying to finish it with each inhale. I asked how he was, and he said he was tired because these performances took away his ability to sleep. We like to imagine that danger sits obediently behind the lines we draw around it, that we know its coordinates, but most of us don’t have a clue. I looked down at the concrete, and as I searched for something to say to him, the crew began pushing the crowds onto the sidewalks. The band’s brass section started playing a raucous version of “The Blue Danube.” A few people sprayed lines of an accelerant along the length of the street and set them on fire. The fleet of motorcycles, wrapped in Christmas lights, rounded the corner and drove slowly along the lines of flame with the brio of parade horses. I turned toward the crowd, looking for Julián, and caught the moment he disappeared into the mass of people.