What should a couturier wear? It’s a question Edmund White put to me during the course of this interview, and the answer is complicated. While a couturière can wear her own creations, a couturier depends on other designers for his clothes. What should a fashion writer wear? A writer’s concern is stylish sentences, which can’t be worn, alas. What does fashion care for words?

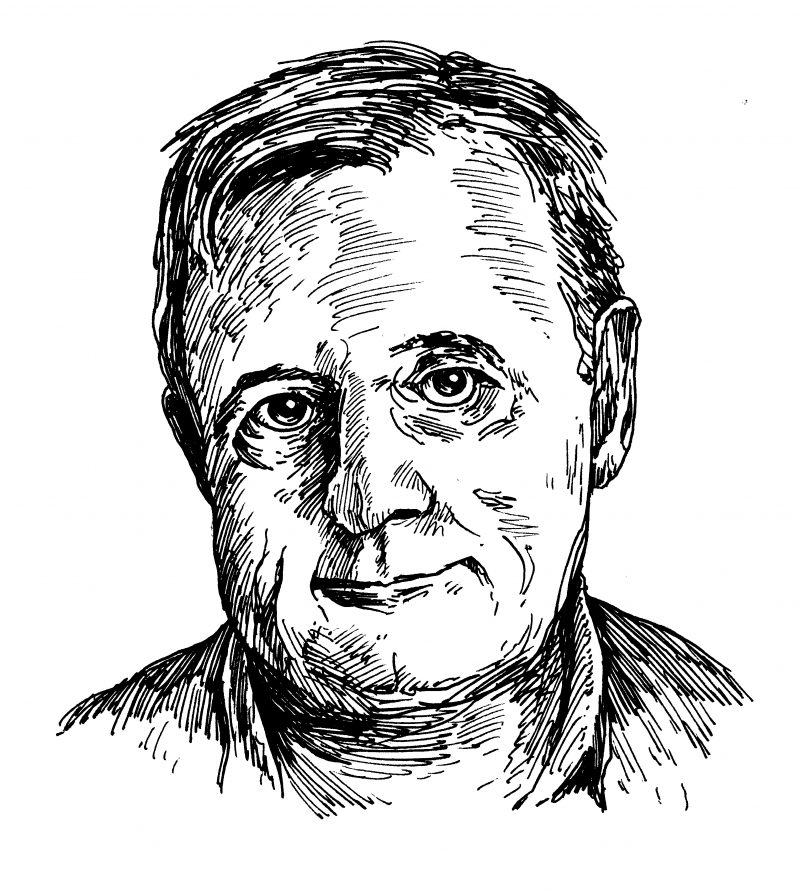

Since he began publishing, in the early 1970s, Edmund White has put out novels, short stories, and all manner of belles lettres. Many are classics: the coming-out novel A Boy’s Own Story, the AIDS-inflected The Beautiful Room Is Empty. His biography of Jean Genet, Genet: A Biography,won a National Book Critics Circle Award.

Inside a Pearl: My Years in Paris is White’s most recent work. It’s a memoir of the decade and a half—from the early 1980s to the late 1990s—that he spent in the capital of fashion. During that time he befriended some of the great couturiers of the day. I asked him about them, and about fashion, and about fashion and writing. I asked him for gossip. He obliged me.

—Derek McCormack

THE BELIEVER: I first saw your work in an issue of Vogue; you were writing from Paris.

EDMUND WHITE: When I was there I wrote for all the Condé Nast magazines. I think they gave me a monthly stipend. It was enough to pay the rent. One of the first things I did was interview Éric Rohmer, and it was absolutely insane because my French wasn’t very good, but I lied about it and said that I spoke perfect French. I could ask the questions, but I didn’t know what he was saying back. I couldn’t ask follow-up questions.

BLVR: You covered fashion stories, too. And you were friends with Yves Saint Laurent?

EW: Yves Saint Laurent was very drugged and drunk and just out of it. He was a fascinating man who could sort of get it together to produce these shows every year, and he probably had the best sense of color of anybody in the twentieth century. But Azzedine Alaïa was my favorite—as a designer but mostly as a person. One of the biggest problems that any couturier has is: what is he himself going to wear? Many of them go for this sort of business suit. That’s wrong, because it looks so common. Savile Row, that’s not right either. Azzedine’s solution was to wear these black silk Chinese pajamas.

BLVR: They’re his signature.

EW: He liked to work all night. I remember he’d have the sixteen-year-old Naomi Campbell—who was a dream, so sweet—on a dais, and he’d run around like Nebuchadrezzar with pins in his mouth, and pin her together. He’s called the architect of the body, unlike Lacroix, who would sort of do a sketch with very little idea of how it would look on somebody, and would hand it over to les petites mains, whose interpretations of the sketch were half the work. Azzedine, he’d do the whole thing himself on the body, sort of like Balanchine, who’d say he created a ballet on a particular dancer.

BLVR: It’s often said that gay fashion designers don’t know how to make women beautiful, or don’t want to.

EW: The myth is that gay men are hostile to women and want to undermine them, want to flatten their breasts and put them in men’s clothing and make them look ridiculous, want in every way to desexualize them and make them ugly. The gay male’s revenge. It’s a pre-1960s view of gay men, based on the idea that gay men were competing with women for men. It’s crazy if you think about it.

BLVR: When you were starting out as a writer in New York, what were gay men wearing?

EW: There was a dichotomy: it was man and boy. The boy was the object of desire. He was slender and starved himself. He wore black pegged pants, black shoes, a powder-blue cashmere sweater, and lots of perfume. He wore his hair long.

BLVR: He was Audrey Hepburn.

EW: This was even before the Beatles. It was OK to be twinky and feminine—he’d have one hand on his hip to excite the men. I straightened my hair to have a surfer look and starved myself a little to be thin. The ideal was the ephebe. Of course, this all came to a crashing end when you were thirty. At thirty, you were no longer attractive. [Laughter]

BLVR: I really shouldn’t laugh. How did you dress when you went to Paris?

EW: I was a Village bohemian who wore jeans with holes in them and leather jackets and T-shirts. In America, it was definitely the Village People look that was considered hot. The hard hat, the jeans and leather vest. I remember David Rieff—he told me that in Paris, just to go to buy a loaf of bread you had to put on a coat and tie, so you better change your ways. I did change my ways. I tried to dress nicely. I had just lost a lot of weight and I could fit into nice clothes. In America, the only sexy image for men was working class men. In Europe, businessmen, intellectuals and professors, artists—all those people could be considered sexy. When I came back to New York, there was a very hot gay guy living above me on Lafayette Street. I remember he said, “Oh, my god, you smell like cologne, that’s so revolting; if there’s one thing I hate, it’s cologne on a man.” And I thought, Oh boy, that takes me back. It took me back to the rules for getting into the Mineshaft: no cologne. Everybody was supposed to smell like old sweat. That was supposed to be hot. [Laughter]

BLVR: Fashion and writing—do you see any similarities between them?

EW: I don’t think it’s so different from painting. It’s painting from fabric. And is painting like writing? I think so. I suppose in some ways fashion is a little more like high-quality journalism, in the sense that it was meant to be ephemeral from the beginning.

BLVR: There’s not very much good fashion literature.

EW: Very little.

BLVR: It’s hard to capture the fashion world.

EW: People don’t really know that world. And I’d say that most novelists are professors on little campuses somewhere; they don’t seem to know much.

BLVR: There’s Zola’s novel The Ladies’ Paradise.

EW: Au bonheur des dames. I know it well. It ends with a great white sale!

BLVR: There’s Mallarmé’s writing on fashion, and there’s Baudelaire.

EW: I’d like to write a book about Baudelaire, but nobody wants me to. I can’t get anybody to commission me, because nobody knows who he is in America.

BLVR: He had such an impact on how we think about perfume, jewelry, fashion.

EW: If you read the history of aesthetic ideas, it is the dullest thing ever written. They repeat themselves endlessly, and they all say only one thing, which is “Imitate nature.” Finally you get Baudelaire, who says, “I despise nature and nothing is worse than a woman who’s natural looking. Women should look artificial and sick.”

BLVR: In your novel Hotel de Dream, Stephen Crane discovers drag queens at a bar in downtown New York. The description of the drag queens is very detailed. You go to town on those girls.

EW: When I first came to New York, I would go to that bar without knowing that it was the Slide, which had been the first publicly acknowledged gay bar in New York. It wasn’t a gay bar when we went there. It was called the Bleecker Street Tavern and it was around the corner from where I lived, on MacDougal between Bleecker and Houston. We’d go there every night. It had these rickety stairs leading up to a condemned balcony. The whole place was almost completely empty. There was this one very tired old waitress, very sweet, waiting on everybody. She had dyed black hair. She was probably a lesbian—she always seemed to perk up when we’d bring girls. Then it became a run-down, awful place called Kenny’s Castaways. I was standing one day on the sidewalk in front of it and I started talking to the owner. He said, “Come with me and I’ll show you downstairs.” There are these little rooms where the prostitutes would take their customers.

BLVR: In gay culture, time is out of time. A writer could describe gay culture to death and not capture the greater culture at all.

EW: It’s like black culture would be.

BLVR: It has to be described.

EW: That’s partly what fascinated me. It’s so different from ours. When I was a boy in the 1950s, the whole idea was to get trade, straight trade, and if they got mean and beat you up, then you’d say, “My trade turned dirt.” It was assumed that no gay person would want to have sex with another gay person. People would say, “What would we do, bump pussies?” That was the thing to say. “What on earth would we do in bed?”

BLVR: I associate you with a certain classic American style. When I see you, you’re often in navy blazers and chinos, or in jeans and a T-shirt. You’re preppy.

EW: Well, I went to a prep school. I’m very middle-class that way. My idea was to blend into the background. I don’t really want to be noticeable.

BLVR: William Burroughs said that the best thing was not to be noticed—the best way to operate in our culture was to blend in. Though he hardly blended in: his suit and tie became a signature style.

EW: Certainly writers want to blend in. I believe that, especially after a certain age, you long for anonymity. Jean Genet felt that you couldn’t be effeminate after thirty without risking ridicule. You had to turn yourself into something butch if you were going to survive as a sexual being, or even as a social being. So he did this major operation on himself. He butched himself up: his clothes, his manner. He shaved his skull. I think he tried to look tougher than he really was.

BLVR: Which a lot of gay guys do.

EW: Genet had pretty much been a feminine prostitute when he was very young. Sometimes, when he was older, he would take lots of Nembutals, eight or nine of them, and he would revert to his feminine side. I met a straight French photographer who had followed Genet around in America. He said, “I don’t want to talk about that guy.” I said, “Why not?” “Oh,” he said, “he was my hero but he disappointed me. If you must know: he’d put on a pink fucking nightgown and dance for the Black Panthers.” I thought, This can’t be true. Genet was so careful about being butch. A year went by and then I interviewed Angela Davis. She said, “Oh, Genet, he was a great man, he was the original gender bender. I remember when he’d wear a pink nightgown and he’d dance.”