In Brian Francis Slattery’s second novel, the collapse of the dollar has led to a slavery based society run by the new boss of Manhattan, a man known as the Aardvark. Facing off against the Aardvark is Marco Angelo Oliviera, a kind of killer’s killer whose stealthy-fast methods seem almost superhuman. Marco is a member of the Slick Six, a scattered and diminished gang of international criminals. Escaping a prison ship, Marco decides to re-form the Slick Six, resulting in a trek from New York to North Carolina, then to Louisiana and on through to California. In addition to tracking down his fellow Slick Sixers, Marco encounters, among others, the New Sioux (a group of Native Americans hell-bent on avenging injustices) and the Americoids (a group of hippie nomads led by Doctor San Diego). He and his cohorts also march deep into his own past, and the country’s past, aided by a psychic emanation called “the Vibe.”

If you think this sounds like Thomas Pynchon or John Calvin Batchelor territory, you would be correct. Slattery’s approach walks a tightrope between absurdism and a kind of accentuated Byzantine realism. The portrayal of Marco, for example, lies somewhere between outrageous comic-book antihero and true three-dimensional characterization. Surprisingly, it soon becomes clear that Marco’s need to bring the Slick Six back together is as much about a nascent sense of family—and proving that he’s still human—as it is about liberating the country.

Still, it’s not the characters so much as the novelist’s roving, restless eye as Marco travels west that gives the novel its true sense of poetry and purpose. Through a series of brilliant descriptions, Slattery writes a love song to a poor, multicultural America that survives on the debris of the past. Kids play with “a soccer ball skinned of its color, patched with duct tape, denim, and glue.” A “colony of dogs lives inside the rusting body of an armored troop carrier.”

These depictions of America transformed are often long, and, in another kind of novel, might have become unwelcome digressions. However, in Liberation most of these sections give the reader a crucial understanding of Slattery’s vision of the future and further illuminate Marco’s own complex past. They also provide the anchor for the reader’s belief in the new slavery that forms the heart of Slattery’s post-collapse economic system. As Slattery writes, “The places that used to sell stirrups, spurs, and license plates to tourists are now flophouses, whorehouses, stands selling heroin and whiskey in tiny increments. Men and women in dirty clothes, tattered cuffs, ragged hems, stand in a jagged line and wait for their fix, to call up their courage, blunt their terror at selling themselves into slavery.” True to the spirit of America, there are “men in sandwich boards selling binoculars, the woman festooned in colored foils selling lollipops, cotton candy, tin toys for the children.” The dollar may be dead, but a severely warped brand of capitalism is still going strong. As the Slick Six gets back together and Marco is stalked by the Aardvark’s enigmatic assassin, the novel’s pace quickens, gaining momentum at the expense of Slattery’s vision of a twisted American dream. The satisfying if inevitable final clash between the Aardvark and Marco is pulled off with skill, but the truly amazing moments come from Slattery’s vision of America, past, present, and future.

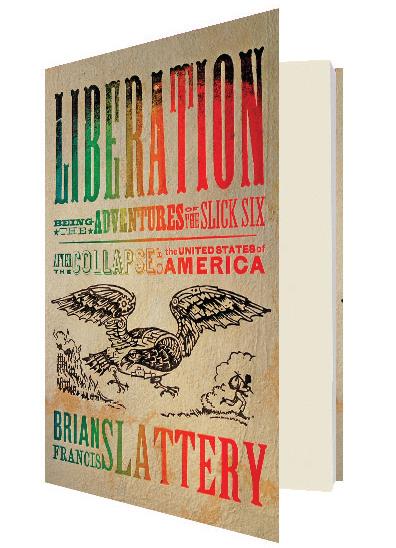

Format: 304 pp., paperback; Size: 5″ x 8″; Price: $14.95; Publisher: Tor Books; Editor: Liz Gorinsky; Print run: 7,000; Song on which the book is loosely based: Bob Dylan’s “Highway 61 Revisited”; Book’s full subtitle: Being the Adventures of the Slick Six After the Collapse of the United States of America; Reason the author had a run-in with police in McPherson, Kansas, while doing research for the book: He inadvertently photographed the town jail too many times; Representative sentence: “Write your anger on the surface of the world in letters of fire, and let them rage until the words have destroyed everything.”