Kiev, November 2004. The streets are alive with the sound of protest, and three days after a rigged ballot, a local singer, Ruslana, expresses her support for opposition leader Viktor Yushchenko. As her press release put it, “Ruslana has announced hunger strike and decided to place a symbolic ribbon around her head upon the news from Ukraine’s Central Election Commission to announce Prime Minister Victor Yanukovich the next President of Ukraine.” But Ruslana isn’t your average buxom Carpathian activist: her engagement on behalf of Ukraine actually started earlier that year when, clad in Xena-like leather and backed by an armada of brawny percussionists, she performed “Wild Dances” at the Eurovision Song Contest—and won. With that success, she followed in the hallowed footsteps of such glorious exponents of pop music as France’s Serge Gainsbourg (author of the 1965 winning tune, “Poupée de cire, poupée de son”) and Sweden’s Abba (triumphant in 1974 with “Waterloo”). But with her activism, Ruslana, née Lyzhychko, also vividly embodied the dizzying conflagration of pop and geopolitics that is the Eurovision Song Contest.

Terry Wogan, who’s been commentating the annual live event for the BBC since 1971, once mused, “Is it a subtle pageant of postmodern irony? Is it a monumental piece of kitsch? Is it just a load of old plasticene?” It’s actually all of the above, with a few key elements Wogan somehow overlooked: nation-building ideals, behind-the-scenes drama, inane choreographies, conspiracy theories, costumes from outer space (or at the very least, outer Croatia), and of course songs that veer from blisteringly stupid to blisteringly brilliant and, just as often, hit both extremes. The ESC may well be the greatest invention in pop-music history.

*

Growing up in France, I faithfully watched the telecast every May. Later, I also discovered punk rock and baroque, German techno and Norwegian black metal; I went to the opera and underground clubs. You might say I expanded my musical horizons. Yet I never got tired of Eurovision. In fact, I started enjoying it more as American and English indie rock got increasingly self-referential, didactic, and joyless. The Eurovision contest is the exact opposite: it’s so garish that it makes Telemundo variety shows look like outtakes from a Bergman movie, and you can always count on surprises, whether it’s a singer suddenly flailing out of tune or one unexpectedly putting on the kind of electric performance that short-circuits TV sets from Dublin to Bucharest. Every time I think nothing can top a particular eye-popping display, another act is champing at the bit in the wings, waiting to get its chance to show the world that his or her country’s pop stars can shine as bright as any others, or maybe just as bright as those from powerhouse Ireland. (Eire has won the ESC more than any other country: seven times, including three times in a row from 1992 to 1994.) As for the songs, yes, many are mind-boggingly awful. But there are as many good songs as there are bad ones, and a handful every year regularly qualify as great pop. So while I can’t deny my enjoyment is somewhat ironic at times, it is also deeply sincere because the ESC offers plenty of what pop is best at: outlandishness, disregard for bourgeois standards of good taste, music as community-building enterprise, and of course lots and lots of disco performed by divas of all genders.

Now living in New York, I buy Eurovision contest CDs by mail order, read Eurovision contest websites (which can sport some of the internet’s most wickedly entertaining writing), and watch Eurovision contest broadcasts on videos mailed from France by my ever patient mother. And yet all this wasn’t quite enough, so I finally broke down and decided to attend the actual event, which that year happened to be the fiftieth-anniversary edition. Which is how on May 17, 2005, I found myself on a Ukraine International flight to the host city of Kiev. An attendant named Stalina poured me a Coke. I knew I was pointed in the right direction.

*

Let’s start by getting some pesky facts and rules out of the way so American readers—most of whom are sadly unaware of the Eurovision Song Contest—can follow. For the past half century, the ESC has been mixing cultural and political truisms faster than you can say “Lithuanian disco.” Inspired by the Sanremo Music Festival, running in Italy since 1951, Eurovision was hatched in 1955 by the European Broadcasting Union (EBU), an umbrella organization gathering public broadcasters, in an attempt to foster cultural exchange between European countries via the international language of pop music. The idea was that each country would nominate a song to represent it in a pacific battle every year. So far, so UNESCO.

Combining musical performances and the judging thereof, the show—which is broadcast live to millions of viewers, not a single one of them in the U.S.—is split into two halves. First, the songs are performed, then there’s a ten-minute intermission during which tele-voting takes place in each participating nation (people can’t vote for their own country). The last hour of the contest is devoted to pure white-knuckle suspense as country after country calls in its points. To quote the EBU’s official rules for Kiev, each nation gives “12 points to the song having obtained the highest number of votes, 10 points to the song having obtained the second-highest number of votes, 8 points to the song having obtained the third-highest number of votes, and so on down to 1 point for the song having obtained the tenth-highest number of votes.… When called upon to announce its results, which must be done clearly and distinctly in English or in French, the spokesperson of each Participating Broadcaster shall first state the name of the country on behalf of which he is speaking and then announce the points allocated to each song in ascending order.” Best of all, the winning country gets to host the contest the following year.

On paper, this looks straightforward enough, but aesthetics and scoring frequently collide, forming an explosion of international intrigue and conspiracy theories, all of which are kept fresh by ever evolving geopolitics and constantly updated contest rules. Factoids, gossip, and reports from far-flung juries are analyzed by fans as obsessively as many men watch SportsCenter; think of it as Monday morning quarterbacking for women and gays, the contest’s most devoted constituency.

Much has been said about the fact that the contest has actually spawned few stars. It’s true that if you’re speaking about worldwide fame, only Céline Dion (winner in 1988 on behalf of Switzerland) and Abba would qualify. But actually plenty of Eurovision acts were doing well enough in their respective countries or in Europe as a whole before entering the contest, and others have parlayed their experience into flourishing careers: Sandie Shaw, Cliff Richard, and Olivia Newton-John have sung for the U.K.; Ofra Haza represented Israel in 1983; Julio Iglesias placed fourth on behalf of Spain in 1970. Now many entries come out of reality TV. (Commentating the 2005 contest for France 3, Guy Carlier introduced a pair of competitors by saying “They’re the winners of Bosnia-Herzegovina Idol. This sentence gives me vertigo.”) But in Kiev, pro or semipro entertainers rubbed elbows with amateurs in the original Olympian sense of the word, like Denmark’s Jakob Sveistrup, who teaches in a school for autistic children, and Slovenia’s Omar Naber, a dental technician whom I saw sitting outside the arena after the contest, talking forlornly on a cell phone all by his unstarlike self. It’s this kind of incongruous sight that made dealing with Ukraine’s idiosyncratic sense of organization worthwhile.

*

Flying to Borispol Airport capped weeks of angst, confusion, and nail-biting frustration. Going to Ukraine was easy enough; going to the ESC in Ukraine turned out to be a trial in which the weak of will and the light of wallet didn’t stand a chance. Securing a hotel room, a press pass, and two tickets for the final consumed weeks of my time in the winter and spring of 2005. It required calling and emailing France, Ukraine, England, and Switzerland, and eventually pleading for help from the diplomatic corps. It quickly became obvious that Kiev and the Ukrainian government took the contest as an opportunity to show the rest of Europe they could put on a show, while local businesses took it as an opportunity to make a quick hryvnia. Unlike other major events, getting a press pass didn’t guarantee access to the show. In fact, it turned out that nothing save perhaps a suitcase of unmarked Euros guaranteed anything: the ticket sale was delayed for weeks; the website was inaccessible; tickets mysteriously sold out even though nobody was able to buy them; a company that somehow seemed to have gotten hold of the tickets appeared overnight and started reselling them at an inflated price. Finally, some string-pulling and a wad of hryvnias secured two prime seats for the final. By then the trip’s bill had climbed to such an alarming high that my Australian travel companion and fellow Eurovision freak Trevor and I figured we’d have to survive exclusively on bowls of cheap borscht and cut the side trip to hot! hot! hot! Chernobyl.

Many of the Eurogroupies traveling to the show every year lacked our steely determination and gave up in 2005 because Kiev was just too chaotic. A Paris tour operator and experienced Eurovision goer told me he prayed a Scandinavian country would win so the contest would run smoothly in 2006. Hosting the ESC is no easy task in any year, but Kiev’s problems were compounded by the fact that thirty-nine countries were slated to participate, making the 2005 edition the biggest one ever.

*

Thirty-nine? “I didn’t realize there were so many countries in the European Union,” you may wonder. Well, there aren’t. Let’s just say it’s easier to convince the EBU’s Geneva telemongers that you can shake your booty than to convince the EU’s Brussels Eurocrats that your balance of payments is healthy and your imams are library-bound pussycats devoted to scholarly research. Turkey, for instance, has been ringing the EU’s doorbell for years, but it first participated in the song contest in 1975 and won in 2004. The EBU’s ranks are even capacious enough to include North African and Middle Eastern nations such as Morocco (which participated in the ESC once, in 1980) and Israel (a three-time winner, competing regularly since 1973). In addition, the explosions of the Soviet Union and of Yugoslavia have created a slew of new nations, all of them dying to put on sequined pantsuits and sing. And so the ESC has grown from seven entries in 1956 to a record thirty-nine in Kiev—Lebanon, which was scheduled to be number forty, belatedly read the rule stipulating that each country must broadcast the concert in its entirety, and it withdrew rather than having to show the Israeli song. I wish the EBU had extended an invitation to Vatican City to fill Lebanon’s slot; after all, Vatican City’s got some great outfits, puts on fab pageants, and is used to convoluted electoral procedures—it would have been a cinch.

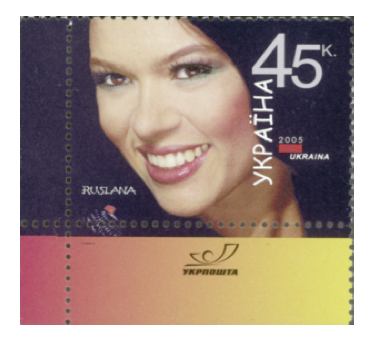

To handle the overflow of contestants, in 2004 the EBU created a semifinal, which takes place a couple of days before the final, in the same city. The top ten finishers in the semi repeat their songs at the grand showdown. They join the so-called “Big Four,” i.e., the countries that fork out the most membership dues to the EBU—France, Germany, Spain, and the U.K.—as well as the ten highest-scoring countries from the previous year, including of course the winner and current host. (Starting in 2007, there will be five “pool semifinals” all across Europe in April, bringing the potential number of countries eligible to participate in the elimination process up to a whopping fifty-five; a total of twenty-five will participate in the final in May.) And in Kiev, there was no way we could forget that Ruslana had triumphed in 2004, a feat seemingly as important in Ukraine’s cultural history as Mikhail Bulgakov finally completing The Master and Margarita around 1940.

*

The best thing in Kiev: buying Ruslana stamps for my postcards. Actually, buying Ruslana everything, from CDs to key rings to coasters. It’s a good thing the singer is easy on the eyes and a charismatic entertainer because she was ubiquitous: Ruslana beamed from billboards; Ruslana starred in TV commercials; Ruslana was sighted on Kreschatyk Street; Ruslana sang at the free outdoors festival; Ruslana was Europartying at the Euroclub; and of course, Ruslana was a guest performer at both the semi and the final, flanked at the latter by dancers who looked like Ming the Merciless’s bodyguards. It was as if she had won the Nobel Prize and an Olympic medal. Unsurprisingly, it wouldn’t be long until the singer switched to politics: in March 2006, she was elected to parliament after running on the Yushchenko list Our Ukraine. (Her bio on that list’s official site taught me that Ruslana got her college degree as “symphonic orchestra conductor” and that her husband is “physician-theoretic by profession.”) I wouldn’t be surprised if she ends up president one day. In the meantime, she is a genuine star and her presence at the semi took a bit of the sour edge off the event.

Not that anything went wrong that evening, technically speaking. Contrary to web gossip suggesting that Kiev’s Soviet-style concrete Palats Sportu (sports palace) would not be refurbished on time and the contest would have to be moved to Sweden, the arena was ready. And the Ukrainian presenters’ English was perfectly adequate, even if they sounded as if they had learned it by watching 1970s game shows. If only tele-voters had been as alert as Ukrainian contractors and made better choices that fateful night…. Holed up in our hotel room (giving up on attending the live semi was one of the purse-tightening measures), Trevor and I almost choked on our lukewarm Rosynka Super Colas when some of our favorites—Iceland’s Selma, Lithuania’s Laura and the Lovers, and Belarus’s Angelica Agurbash—didn’t make the cut. Was it because Selma’s red pedal-pushers were so hideous that they distracted from her nifty up-tempo number? Did voters eject Angelica (Miss Photo USSR 1991) because if the organization in Kiev was bad, everybody knew the capital of an impoverished police state would be worse? Did Laura fail because her official bio revealed she had once sung backup for the Scorpions? At least the four women in the wonderful Vanilla Ninja made the cut. Who cares if they were Estonian mercenaries representing Switzerland?!

Extraordinarily enough, contestants don’t have to be from the country they’re representing at the Eurovision contest, a loophole that’s long been exploited by small nations—the odds of Andorra and Monaco unearthing a new pop star every year are pretty low. So nobody batted an eye when in 2005 the wily Swiss recruited a quartet of foxy Tallinn girls with a burgeoning career in Germany. And the Ninjas weren’t the only traveling Wilburys in Kiev: Belgium’s Nuno Resende was born in Portugal; Finland’s Geir Rønning was born in Norway; Andorra’s Marie-an van de Wal was born in the Netherlands; Turkey’s Gülseren was born in Turkey but has been living in France since she was seven.

Even Britain, which would appear to have access to a deep pool of homegrown talent, has always cast a wide net, recruiting Australian Gina G in 1996, for example, or Kansas-born Katrina Leskanich and her Waves in 1997 (they won). Like a busy Eurocuckoo, Katrina, now Waveless, even tried to find yet another nest and entered the Swedish national selection process, aka Melodifestivalen, in 2005; much to her surprise, she wasn’t picked. Still, perhaps this fluidity illustrates a great achievement by the European Union: the free circulation of people within a borderless continent—at least when it comes to singers, not Polish electricians or Kurdish refugees.

And so Vanilla Ninja went on to the final, along with Trevor and me. We were in exotic company: the twenty-four competitors hailed from countries as diverse as Moldova and Israel, Malta and Russia, an impressive range that helps explain why the contest is so entertaining. In comparison, Americano-American brawls come off as hopelessly self-aggrandizing and downright provincial. American Idol? Excuse me, but second-guessing intra-Baltic rivalries or post-Yugoslavian alliances is a lot more captivating than watching an Alabaman and a Texan face off while a trio of judges looks on. This is a simple fact of life that NBC obviously didn’t grasp when it announced in the spring of 2006 that its own version of Eurovision would include contestants from all fifty U.S. states. Whoop-de-do!

Yet nationalism remains decidedly good-natured at the contest. Waiting to enter the Palats Sportu, I spotted fans with national colors painted on their faces cheer denizens from rival countries. A gang of Swedes wearing matching IKEA T-shirts cordially posed with a man waving a fabulous red-and-black flag that looked as if it had been pulled out of the Tintin book King Ottokar’s Sceptre but turned out to be from Albania. A man holding a Turkish flag embraced a gaggle of Greeks, seemingly unconcerned by the fact that the two countries have been at each other’s throats over the Cyprus issue for more than thirty years. You don’t see that kind of effusion at a European soccer match, as anybody who’s ever fled from drunken hooligans can testify. At the Palats Sportu, sportsmanship reigned, and the only display of rowdiness came when Belarus was soundly booed for awarding twelve points to Mother Russia. This is what the world would look like if women and gays ran it, I thought, drunk on the excitement of it all.

*

But what does it all sound like? In 2005, Dr. Harry Witchel, a teaching fellow in Bristol University’s Department of Physiology, isolated the key elements making up an ESC winner. According to him, they are pace and rhythm; an easily memorable song; a perfect chorus; a key change; a clearly defined finish; a dance routine; and a costume (presumably something sparkly). As vague as that list is, it’s still easy to see that it pretty much rules out rock. In fact, the Eurovision contest embodies everything that is not rock and, by extension, America.

Like Bollywood, the ESC represents pop culture that happily thrives outside the U.S. Of course, both Bollywood and Eurovision integrate references to American-born idioms, but these idioms aren’t considered any better than any number of others such as schlager or variété (locally rooted popular musical styles from Germany and France, respectively). Both predate rock, and while I can’t deny that both carry a certain amount of cheesy baggage, they also can be supremely melodic. Over the years, many Eurovision-spawned songs—Séverine’s “Un banc, un arbre, une rue,” Lena Philipsson’s “It Hurts,” Baccara’s “Parlez-vous français?,” the aforementioned “Waterloo” and “Poupée de cire, poupée de son”—have held a special place in my heart because they are so irresistibly catchy. In fact, only three acts could have remotely been considered to have played rock in Kiev—and what rock! Zdob si Zdub may have been Moldova’s answer to the Red Hot Chili Peppers, but they also brought a drum-beating granny on stage; Vanilla Ninja sounded like Electric Light Orchestra covering “March of the Valkyries”; Norway’s Wig Wam looked like middle-aged glam sausages encased in silver spandex and topped with fright wigs. Americans may take this as yet another sign that Europeans can’t rock; I take it as yet another sign that Europeans don’t care about rock. Not the same thing at all.

While most of the Kiev songs would be anathema to Smithsonian-addicted world-music purists, enough of them kicked plenty of ass by glorifying melodicism and arrangements descended from Phil Spector’s “bigger is better, more is more” school. The Kiev contestants also relished mixing and matching pan-European influences with exotic spices, often producing stunningly lumpy stews. Christof Spörk, from Austria’s Global.Kryner, explained that “the concept of our music is Alpine music…. It combines Austrian and Slovenian music with Cuban music.” In its press bio, Hungarian band Nox stated that “we build a bridge between the ancient Hungarian pentatonic scale with the world of contemporary music.”

Indeed the biggest ESC trend over the past few years has been the incorporation of ethnic flavoring in both the music and the ubiquitous dance routines. Ruslana’s “Wild Dances” drew from the folk stomping of Carpathia’s Hutsul people, and her victory in 2004 led the following year to a veritable epidemic of tribal drumming and traditional outfits customized for maximum garishness. A couple of acts mining the turbo-ethnic vein did stand out in Kiev: Nox benefited from a catchy song and a group of black-clad dancers looking like Riverdancing Darth Vaders; Sistem, the backing band for Romania’s singer Luminita Anghel, ended its set by power-sawing the oil drums it had been banging on, Einstürzende Neubauten–style. At least disco—which has been a constant at the contest since the mid-’70s—is likely to remain after the ethnic fad wanes.

No matter the style, however, covers are forbidden. My favorite Eurorule among many, many Eurorules is that songs cannot be longer than three minutes; think of the rules as pop’s answer to the constrained writing favored by the French collective OuLiPo (Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle). This constraint makes the songwriters contort themselves in order to stand out within a strict time limit, though whether they write a power ballad or a dance-floor scorcher, they somehow all end up writing in a bridge at around the second minute, following it with a key change, and concluding with a grandiose finish. Brilliant! This is enough to make up for the fact that no more than six performers are allowed onstage for each country, and that the magnificent orchestras of yore have been replaced with backing tracks (all vocals are performed live, though).

*

The language rules are a lot more flexible. Contestants have been free since 1999 to sing in whatever language they want; essentially this means they are free to sing in the unique tongue known as English as a Second Language. The lyrics aren’t usually completely wrong, but they often feel slightly off and aren’t helped by deliciously accented pronunciations. Watching the semi, for instance, I was delighted to hear Vanilla Ninja sing “I can see the danger eyes / In your eyes,” though it later turned out they were singing “I can see the danger rise / In your eyes.”

Save for pockets of resistance in the Balkans, the biggest exception to the ESL tsunami remain the French. These days, France stands tall (or not so tall, actually, since its candidate, Ortal, was next to last in Kiev) in a depleted Francophone field—especially after neither of 2005’s other Francophone entries, Monaco and Belgium, made it to the final. As Bruno Berberes, head of the French delegation, put it, “In France, we want every country to be made to sing in its native language. It makes it more interesting. [In 2004] we had twenty-four countries in a row singing in English, and so songs in French have no chance.”

Bruno, please! I can guarantee you that the Palats Sportu’s semi-catatonic state during Ortal’s performance had nothing to do with her singing in French and everything to do with her singing a bummer of a tune that mysteriously lacked anything resembling a chorus. When I went to buy ice cream and dumplings from the concession stands during the endless point-attribution segment, I overheard a French delegation member hiss to another, “It was the dress! That dress was terrible!” But perhaps Ortal’s dress wasn’t terrible enough. Perhaps we would have a chance if the exception française could just stop trying to be so classy, give up on the thoughtful lyrics and the meaningful choreography and just go for the sequins, the Hi-NRG, or, if all else fails, the pentatonic-tribal combo. But no: following its pattern of inventing institutions only to grow bored of them (RIP countless constitutions including the European one), France has been dragging its Eurovision heels for the past fifteen years or so. Perhaps we should submit an entry in Volapük or Esperanto. At least there would be an element of surprise, because surprisingly for a contest where stunts are common, nobody’s ever performed an entire song in either language. But then some contestants’ English is so… unique, it might as well be Esperanto.

*

Much mirth has derived from the inane lyrics of Eurovision contest songs. The Kiev rulebook stipulated that “the lyrics and/or performance of the songs must not bring the Eurovision Song Contest into disrepute.” Ahem. Over the years, many countries have played it safe by finding refuge in onomatopoeia or filling verses and choruses with an abundance of la-la-las. Most eschew intentional irony; only a few have dabbled in anything that could be construed as postmodern (when you’re from Moldova or Belarus, two of continental Europe’s poorest countries, you’d very much like being modern before you can even consider being post); even fewer have had political lyrics.

Politics are officially unwelcome at the ESC. In the past, some countries have withdrawn to make a point; in 1969 Austria, showing the kind of spine it lacked in 1938, refused to go to Franco’s Spain. On the other hand, messages in songs have tended to be couched in hazy rhetoric. In 1977, for instance, Austria’s Schmetterlinge attacked the music business in its entry “Boom Boom Boomerang,” which opened with “Music is love for you and me/ Music is money for the record company.” Of course it then went on to a biting Eurochorus of “Boom boom boomerang, snadderydang / Kangaroo, boogaloo, didgeridoo / Ding dong, sing the song, hear the guitar twang / Kojak, hijack, me and you.”

There wasn’t anything remotely that poetic in Kiev. Ukraine’s Greenjolly had to change the lyrics to its entry, “Razom nas bagato”—a popular chant during the Orange Revolution a few months earlier—after the EBU’s Song Contest Supervisor, a Swede named Svante Stockselius, expressed his disapproval. Greenjolly obligingly tweaked its lyrics, though its Midnight Oil–style anthem still kicked off with the line “We won’t stand this—No! Revolution is on!” and its singer wore a Che T-shirt. Meanwhile Russia’s “Nobody Hurt No One” started with “Hello sweet America, where did your dream disappear? / Look at little Erica, all she learns today is the fear / You deny the truth, you just having fun / Till your child will shoot your gun.”

Of course, being political very often has nothing to do with lyrics. Echoing Bollywood’s signature style, the ESC represents music as a vessel for liberation and identity through over-the-top performances, larger-than-life singers, and the idea that every number should be a friggin’ show. Is it any wonder, then, that the more flamboyant fringe of the gay community likes the contest so much?

While same-sex love songs haven’t been entered, at least officially, the ESC is more gay-friendly than most international competitions. The turning point came in 1998 when Israeli transsexual Dana International won with “Diva.” Israel’s Orthodox community didn’t appreciate being represented by a statuesque tranny, but millions of Euroqueens rejoiced. In 2002, Slovenia picked three men dressed as female flight attendants to go to the contest in Tallinn. The following year, the two surly mock-bians of t.A.T.u briefly held hands onstage while singing for Russia, and in 2004 Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Deen lispily performed the unofficial anthem of the crystal generation (“I’m lying, I’m late, I’m losing my weight / Because I want to dance all night / Because I want to stay all night / In the disco, in the disco”) in what may well have been one of the gayest performances of all time.

In their book The Complete Eurovision Song Contest Companion, Paul Gambaccini, Jonathan Rice, Tony Brown, and Tim Rice muse that “MTV, the cultural glue of the younger generation of European music followers, has nothing to do with Eurovision: the culture gap seems to be not between Estonian and French but between those over thirty and under thirty.” I would actually argue that the gap is between those for whom pop is a way of looking at the world and those who dismiss it as pap.

In contrast with rock’s constant search for “authentic” roots and worthy artistes to bring them forth, pop and disco celebrate artifice and masquerade. Just look at Eurovision 1982, when twelve of the eighteen contestants had one-word names that reeked of time-shares in Bratislava: Nicole, Stella, Svetlana, Bardo, Chips, Mess, Lucia, Doce, Aska, Neço, Brixx, and Kojo. If you find this list appallingly dumb, there’s no way you could ever enjoy the ESC; if it makes you laugh in delight, you’re also the kind of person who knows that Nicole remains Germany’s one and only winner.

And instead of being defensive, fans fight back. Before and even during my trip, I prepped by reading several Eurovision websites—some, like esctoday.com or eurovision-fr.net for their straightforward news; others, like the Schlagerboys’ entries at popjustice.com, for their cheeky humor. Many of the writers on these sites dismantle rockist pretension with humor and verve. They know perfectly well how surreal it is to be mocked by guardians of musical purity who then go on to worship acts as jejune as the Arcade Fire or Arctic Monkeys.

*

Many countries don’t mind being represented by, say, a campy dude wearing a gold lamé cowboy costume (Germany, 2000). Said nations care even less if they used to be communist. In a 2005 New Statesman article, Tim Luscombe wrote: “In recent years, Estonia, Latvia, Turkey, and Ukraine have taken Eurovision extremely seriously. Estonia and Latvia realized that membership of the EU lay beyond the gates of Eurovision triumph. These countries saw winning Eurovision (which would make them the contest’s hosts in following years) as a chance to showcase their European credentials and hasten EU membership. And they were right.” Or, as Marcel Proust once put it, “That bad music is played, is sung more often and more passionately than good, is why it has also gradually become more infused with men’s dreams and tears. Treat it therefore with respect. Its place, insignificant in the history of art, is immense in the sentimental history of social groups.”

The contest is a huge deal for postcommunist, poorer nations. The Ukrainian authorities and the Kiev municipality went to great lengths to show their capital city could host a major event. The streets were spotless, even during street fairs at which beer cost about seventy-five cents a liter; kiosks manned with English-speaking students were set up at popular spots to help lost tourists; we could not have asked for a nicer frisk from the Palats Sportu’s impassive, high-cheekboned security force. And once we reached our seats in the arena, we could glimpse President Yushchenko, who handed out the trophy at the end. In a brochure distributed to journalists in Kiev, Belarusian Minister of Culture Leonid Guliako asserted that his country’s participation in the contest “is certain to be a worthy contribution to the process of Belarus’s integration into the European cultural space.” (Although while the power of disco could integrate pretty much anybody into the European cultural space, a move into the European political space would be greatly facilitated if President Aleksandr Lukashenko weren’t so keen on keeping his country under a dictatorship.)

Because the stakes are so high for so many, outlandish behavior isn’t limited to the stage: the machinations start with the national selection processes, which are administered by the companies broadcasting the Eurovision contest in their respective countries. Typically, the road to Kiev was littered with histrionics as exquisitely colorful as what took place at the Palats Sportu. During its selection process, for instance, Russia’s Channel One was said to have manipulated the SMS results so that its favored candidate, reality-show contestant Natalia Podolskaya, would be picked. In Bulgaria, runner-up Slavi Trifonov accused winning band Kaffe of rigging the SMS votes; then Kaffe’s song “Lorraine” (and its immortal line “I can still remember Lorraine in the rain”) was accused of plagiarizing a 2001 song written by… Trifonov’s company. Things got a lot more serious in 2006, when the Serb and Montenegrin factions of Serbia and Montenegro clashed during their national selection process, leading to a nasty feud that almost eclipsed the concurrent death of Slobodan Miloˇsevicˇ and led the country to withdraw from Eurovision altogether when it couldn’t agree on a candidate.

*

But in truth, most of the conflicts swirling about the contest don’t arise from the songs or from the singers’ sexualities but from the voting—or more precisely from the way the voting is interpreted. Indeed for many ESC aficionados, the allocation of the points by the participating countries is just as fun as the performances.

In a 2005 paper titled “How Does Europe Make Its Mind Up? Connections, Cliques, and Compatibility Between Countries in the Eurovision Song Contest,” four Oxford scholars noted that “Irrespective of whether it contributes anything to the advancement of music per se, the Eurovision Song Contest does provide a remarkable and unique example of an annual exchange of ‘goods’ and opinions between countries. Going further, it is arguably the only international forum in which a given country can express its opinion about another, free of any economic or governmental bias.” Which doesn’t mean it’s free of controversy, as every single year, accusations of bloc voting surface. Frankly, they are getting a bit tiresome, and I for one just don’t believe they explain either poor showings or victories anymore, if in fact they ever did. Yes, countries often end up voting for their neighbors or for nations with which they have a cultural affinity. Yes, Cyprus will give twelve points to Greece, which is likely to return the favor. Yes, nobody will blink if the Scandinavian countries give each other a fair number of points. But Malta, to name but one, doesn’t have many obvious allies and still made it to No. 2 in 2005, while Sweden was so mediocre that even its Scandi neighbors deserted it and let it sink to an ignominious No. 19.

While phone voting is seen as more democratic and less riggable than the previous system of local juries (two words: ice skating), it’s also led to intense lobbying as many participants make promo appearances all across Europe in the weeks leading up to the contest in the hope that tele-voters will be familiar with them come final time. Many continued to try to gain visibility in Kiev. There were meet-and-greet parties almost every night at the Euroclub, and contestants tirelessly worked the streets. Everywhere Trevor and I went, for instance, we ran into Spain’s Son de Sol, aka the triplets from Seville, filming spots and chatting up vendors at local markets. The effort didn’t pay off for them, but lobbying for weeks definitely is the wave of the future. In a refreshing change from the usual sour grapes and mud-slinging, Swedish TV producer Anders G. Carlsson admitted, “We’re impressed with how the Eastern Europeans have approached the competition. Down here we almost feel like country bumpkins. We should try to adopt their methods.”

The former Eastern countries tend to be the most active in pre-contest legwork because the Eurovision contest means a lot more to them than to the jaded French or Brits. Belarus was rumored to have spent one million Euros on a months-long campaign during which its candidate, Angelica Agurbash, visited several countries. Accredited journalists were deluged with promotional material aimed at helping us fully grasp the subtleties in Angelica’s song: “It has been a longstanding tradition of the Belarusian pop scene that composers collaborate with the best contemporary poets.” One can only assume it’s the latter who, in an act reeking of pure Soviet realness, translated what Angelica sang (“I’ve got no hesitation / It’s my infatuation / Your touch is an obsession / I’m addicted now,” etc.) into what appeared in the official transcript of her song in the Kiev press handbook: “She was standing near a window, / And her beauty was like a trap, / She was shot by sunny beams, / And gave herself up with an open heart, / With all her essence: / All that she took / Was working and boiled, / And only an adult dream / To feel the woman in / Was realised when / They’ve decided to be tied up by Hymen.” (Laugh, hipster, laugh! After all, it’s easier than admitting that these lyrics are no more ridiculous than “I make trips to the bathroom / Yeah my friends all have true grit / I am speckled like a leopard / I’m a specialist in hope and I’m registered to vote / Why don’t you come into my barrio / We’ll see if you can float.” Perhaps Interpol should consider calling Minsk’s best contemporary poets.)

Unfortunately, despite two costume changes and the gayest dancers in the entire contest, Agurbash failed to make it to the final; the chink in Belarus’s diabolical plan was that its singer turned out to have a grating, metallic voice. She was last seen right after the semifinal debacle, leaving the Palats Sportu in both a huff and a van with black-tinted windows. At least Belarus made up for this failure when its representative, the terrifiying moppet Ksenia Sitnik, won the Eurovision Junior Contest later that same year. Yes, despite having reached middle age, the ESC spawned a love child in 2003: the Eurovision Junior Contest, which is open to kids aged eight to fifteen. I was particularly taken by Spain’s Maria Isabel Lopez Rodriguez, who won in 2004 with “Antes Muerta que Sencilla.” That title translates as “Better Dead Than Banal,” which might as well be Eurovision’s unofficial motto.

*

While losing countries complain of bloc voting, they should look closer not only at the realities of modern promotion but also at the fact that England, France, or Sweden won’t always define the parameters of European popular music, and the burgeoning idea that these old-school powers won’t always define the parameters of European politics. The pendulum swung westward once; it can very well swing the other way: in his New Statesman article, Luscombe pointed out that “the political topography of Europe (and the ESC) has changed. The center has moved east. And some people are scared of that.”

It was not all that surprising, then, that Greece triumphed in Kiev, bringing the trophy back to the cradle of civilization. Even less surprising, Helena Paparizou stormed to the top with a classic formula in which a turbo-ethnic vibe was laid onto a strong dance foundation; the news that Paparizou was raised and lives in Sweden came as no big shock, either. Call me utopian, but to me this is precisely why there may be hope for Europe after all.