“What’s the hacksaw for?” I ask Mark Twain. “For these.” He grabs a stack of bamboo rods from the back of his car, and adds a large butterfly net, thick rolls of duct tape, a hammer, poster board, ribbons, and a stapler. The early evening by Capitol Hill throws the ineffectual shadows of office buildings across us, the air convecting heat up from D.C.’s sidewalks; you can smell the gypsum getting baked right out of the concrete.

“OK,” says his friend Tim, rubbing the sweat from his mustache and adjusting his glasses. “Let’s go.”

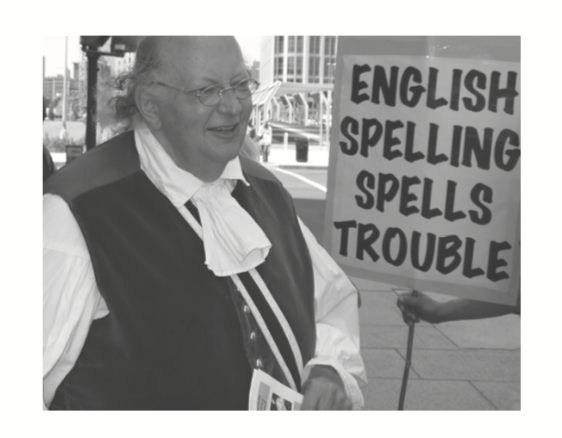

We slip unnoticed up to room 606 of the Grand Hyatt. Canasta cards lay untouched on a side table, along with Ziploc bags of metal badges and boxes of brochures. An international team of eight protesters is waiting, representing the London-based Simplified Spelling Society, New Zealand’s Spell 4 Literacy, and both U.S. and Canadian members of the American Literacy Council. They’re engineers, retired teachers, temporary Mark Twain impersonators—and they are all spelling activists.

One of them examines the goods.

“A net?”

“It’s for catching bees.”

Out comes the hacksaw and they all set to work, cutting down the bamboo to the right size, and duct-taping picket boards to the slender rods. The average age here is about sixty-five; after traveling thousands of miles from around the globe, grandparents are getting stumped by a craft project. Pete Boardman, a retired bus driver from Groton, New York, reddens as he relives every bad art day he had in second grade. He hacksaws unsteadily, tries unsuccessfully to staple into the bamboo, and then he tangles with the tape.

“Use rubber cement,” counsels Niall Waldman, a Glaswegian transplant to rural Ontario. He grew up in the same area and time as comedian Billy Connolly, and he retains the same mischievous burr as he warns that the signs will need to be strong. “Some of the parents can get pretty testy. They’ll break your pelvis.”

A cardboard box of a thousand brochures bearing ALC and SSS acronyms stands at the ready, illustrated with portraits of Benjamin Franklin and Mark Twain and proclaiming: helping more people learn to read, write, and spell. Both organizations descend from spelling reform groups dating to the 1870s. At its peak in 1919, the SSS alone had as many as 2,972 members; it now has only 82, and the ALC has just 12. But like their mighty forebears, they’re on a crusade against illiteracy, delinquency, and poverty—all traceable in some degree, they believe, to the English language’s inhospitality to new learners among children and immigrants....

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in