In a roaring expanse of arid glacial till sits the Maryhill Museum of Art, a burly concrete building. It’s perched on the edge of the Columbia River Gorge, five hours southeast of Seattle, engulfed by a landscape that miniaturizes any architectural gesture. Most of its dozens of windows have bars over them, or have been cemented over, like closed eyes. It is as though this Flemish-style château stumbled along the Lewis and Clark Trail, stopped to rest in this valley where the wind blows as violently as a waterfall, and fell into a coma. Actually, Sam Hill built it as a house for his family, but they never moved in. He converted it into a museum at the urgings of a modern dancer named Loie Fuller and with the help of Queen Marie of Romania, and now people come to visit, but the building does not wake up. Time magazine called it “the world’s most isolated art museum” when it opened on May 13, 1940. Its nickname is Castle Nowhere.

Entering is like going inside a stone. Through the tall doors, past a gift shop, and into the creaky great reception room of the mansion, it dawns on you that the nickname has as much to do with the remoteness of the location as it does with the building’s persistent napping, its ability to remain unconscious in the midst of a rushing natural spectacle, to insist on not being here at all.

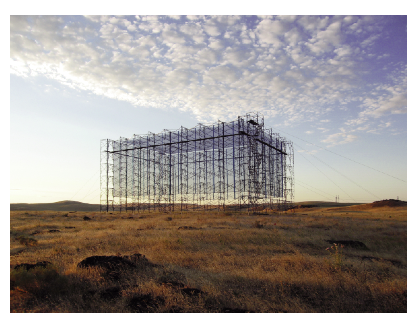

Weirder still, this summer the Maryhill Museum had a double. It was a real edifice, of the same shape and size as Maryhill, just across the canyon. You could walk in and around it and climb the stairs. Two artists named Annie Han and Daniel Mihalyo built it, out of metal scaffolding and blue construction netting, and then they tore it down again, leaving only a patch of worn grass, as if the double, too, had been a dream. Not only had it not seemed real, but the museum hadn’t wanted the double in the first place.

The Maryhill Museum is curmudgeonly in more ways than one. It has a faint regional reputation, mainly among tourists, predicated on the docile promise of classicism. On the surface, the estate is the perfect portrait of bygone aristocracy. The rigid building is outfitted with a collection of Rodin figures and fragments, and flanked by a manicured lawn and gardens that are home to a handful of strutting peacocks. With few notable exceptions, the world responds to the museum’s unconsciousness in kind, remaining blind to its evident oddity and its eccentric history of failures, disappointments, absurdities, and step-celebrities, and especially to the unhappy story of its founder, Sam Hill.1 He was great man and a crackpot, someone who could amass wealth and power but could not hang on to it, and who had an intense fear of invading hordes and a habit of commissioning highly irregular architecture.

The layout is simple enough. On the exterior, the only features that embellish the concrete box are driving ramps built like wings, each connecting to the building at a wide door. This design allowed visitors to drive right through the building—Hill was a pioneer road builder—as though it weren’t even there. Staircases at either end provide horizontal and vertical circulation through the three floors of the museum. Typically, museum interiors are conjoined to art chronology, but there is no logic to the displays at Maryhill. They are laid out like props in a perplexing dream: Romanian royal artifacts and American academic paintings on the main floor, plaster casts of famous busts in anterooms under the stairs, Romanian peasant costumes on the top floor along with contemporary figurative and landscape paintings, and an assortment of Rodins (mostly casts, some lightly erotic drawings) and Native American baskets on the carpeted ground floor, which feels like a basement. Somewhere, in storage, is a world-renowned collection of French haute couture made for mannequins one third the size of humans that was taken on a tour around the world in 1946.

Across the canyon, on the other side of the Columbia, the land is a mirror image of the place Hill came across 101 years ago, when he bought seven thousand nonirrigated, wind-punished acres, hoping foolishly that they would blossom into a Quaker community and a farming village. In the dry heat of July, the tiny blue shivering mirage called the Maryhill Double arose in the middle of the museum’s storied panoramic view.

Getting to the Double from Maryhill meant meandering down toward the river, crossing the bridge, passing the Biggs Nu-Vu Truck Stop Motel, maneuvering along a loopy road up the Oregon side of the gorge, leaving the car by a huddle of Dumpsters where rattlesnakes like to congregate, and walking a dusty path for a quarter of a mile until the watery-looking Double appeared, floating like a jellyfish in the sky. It was possible to see both edifices simultaneously at certain points on the journey, out the front and back or opposing side windows of the car. But the view naturally flowed from the Double to the museum; the Double was a feisty apparition facing off against its more bodily form.

Based in Seattle, Han and Mihalyo are architects who also work as collaborative artists under the name Lead Pencil Studio. They’d studied at the University of Oregon and had been fascinated by Maryhill for years.2 They wanted to build their Double right on the back lawn of the museum, up against the building. The museum refused, claiming logistical difficulties. Another implicit reason may have been that the Double would freak out the tourists, bust up the historical facade of the place. Either way, the final placement of the Double was right. Maybe closest to the truth is that this is a building that does not want its portrait made.

*

“Sam Hill followed every idea until it completely failed,” said the realtor selling Hill’s mansion in Seattle this summer (price tag: $4.5 million).

It’s true. He rose to the top of his father-in-law’s railroad company in Minneapolis, then left abruptly (most likely he was forced out) for the Pacific Northwest, where he bought a gas business, lost money, and sold it, acquired a telephone company that was handily defeated by a competitor, and purchased the land to create his own cherished town next to the gorge. “Where the rain and sunshine meet!” was his sales pitch for Maryhill, where his own family mansion would be like the county seat. But nobody came. No Quakers. No farmers. Hill converted the land into a sleepy cattle ranch and seldom visited. Even the homestead was a bust. Hill’s wife left him, his daughter was institutionalized with schizophrenia, and his son disliked him. They never moved into the château, and neither did he.

Finally, his friend the dancer convinced him to turn it into a museum, and Queen Marie agreed to dedicate it. (Hill had earned the loyalty of the queen by helping Fuller raise money for Romania after the war.) In 1926, when the queen made her feted procession across the country to introduce the Maryhill Museum to the world, she found the repository of her long-hauled treasures unfinished, a home only to mud swallows and rats. It wouldn’t open for another fourteen years, nine years after Hill’s death.

Making a twin of Maryhill had an internal logic, since the museum is a twin of Hill’s neoclassical 1909 Seattle mansion. The Washington, D.C., firm of Hornblower and Marshall designed them both. But the replication extends further. The Seattle mansion, which Hill described as “Grecian Doric” but which is more like a dour version of the Parthenon in which all the spaces between the columns are filled in, is an imitation of Marie Antoinette’s pleasure dome, Le Petit Trianon, at Versailles. All this pharaonic classical copying is hardly surprising for an ambitious, nouveau-riche businessman such as Hill, whose story was pure Americana. From modest beginnings, he studied at Harvard and went on to dip his fingers into every futuristic venture of his era. He tossed off memorials the way some businessmen leave a trail of photocopies—the Seattle and Maryhill houses, the Peace Arch at the U.S.-Canadian border in Blaine, Washington, and a full-size concrete replica of Stonehenge three miles down the road from Maryhill, near which Hill is buried. Hill’s son, James, declared Maryhill “a big fake.”3

Like Hill was, the artists were determined4 to realize their plan regardless of the hostility of the environment. They tracked down the private owner of the empty parcel of land across the gorge from the museum and convinced him to let them use it. He helped them get the project zoned as a temporary billboard, advertising nothing except maybe the unbridled hubris of Sam Hill.

*

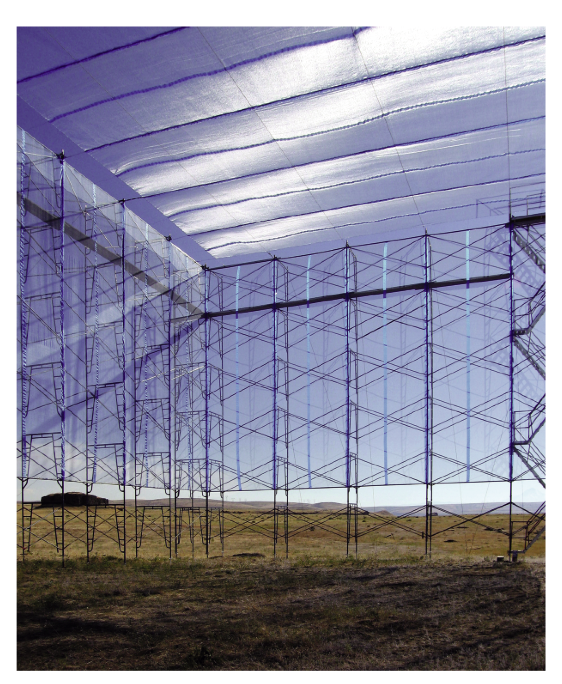

Unlike Maryhill, the Double was one with its environment, with the colored sky, the hilly miles of yellow-brown brush in every direction, the river below, the incongruous snowcapped mountains in the distance. Whichever way it faced, that’s what it looked like from within. In place of concrete walls and a roof, it had a translucent skin of azure construction netting that sparkled in the sun and moonlight, attached to Xs of metal scaffolding and pulling against them in the wind. The netting did not stretch all the way to the ground but left a roughly human-height opening all the way around the base—an implied door, and then, from the inside, the ultimate picture window. The membrane between indoor and outdoor was permeable; air, insects, and vision passed at will. Interior was still exterior. This was like Maryhill-vision—what Maryhill would see if ever it opened

its eyes.

This porousness would have been Hill’s nightmare. He liked to build bars on windows, but these were bars as windows, sectioning the land and creating a multifaceted lens. The views proliferated, as if providing rapid eye movements to accompany the museum’s dream, and the sapphire screen added a dimension of reverie. The Double kept a frontal face toward Maryhill, but the real museum was only one view, taken in all at once, and so diminutive from this distance that a single small section of scaffolding bars formed a frame around its entire concrete hulk, as if capturing it in a photograph and setting it aside as a decoration. Meanwhile, all the other “windows” of the scaffolding diffused and diffracted the landscape, and dematerialized the implied volume of the empty Double. In the wind, the bars cast a curving shadow on the slightly puffed-out netting, as though the whole structure were melting.

The Double swayed gently, which was unnerving for those who climbed the staircases at either end to get to the bird’s-eye view from the top. Scaling the structure to see the climactic panorama was a reward tossed to the intrepid art tourist, but in fact, there’s no roof access at the original Maryhill, and that narrative of completion was totally beside the point. The Double was about seeing in all directions at once, including through walls. The artists had smashed in the windows of Maryhill, torn down the walls, and the views that came spilling out were like the light that rushed through the crack when Gordon Matta-Clark split derelict buildings down the middle in the 1970s, releasing their inner lives. All that was left of the original were its plans, its origins—the sight of virgin scrubland, the dream of a place, the architectural drawings, and, finally, the scaffolding. As the poet Lisa Robertson has written, scaffolding is a process, not an object, “a system, not an organism,” “an analogy,” “architecture’s unconscious displayed as a temporary lacework,” a rabbit hole through which we “glimpse volition tarrying in the visible.” Lost volition remapped onto the original in this resounding stereovisual process was like the kiss of a prince. Maryhill awakened, and came rushing into the empty Double. Sam Hill came back to life, if only for a summer.

*

“Are you in the market for a castle or a mansion?” the Seattle realtor asked me when I called. I lied, told her my parents on the East Coast might want to buy something like this, and that I was scouting for them, because I knew that as soon as she saw me she’d know I don’t have $4.5 million. She didn’t believe me for a second and she let me in anyway.

It was serendipitous that the house was up for sale during the run of the Double: all three of the relevant structures were taking visitors simultaneously. The entrance to the Seattle mansion is a short, curving concrete staircase set away from the street in a sylvan residential neighborhood. Inside, the house is nothing like Maryhill; it has low ceilings and smaller rooms, having been cut up and rearranged several times.5 The reason the interior is so flexible is that all the weight of the building lies on the exterior walls, which are ten inches thick and made of steel and concrete. “This is the most overbuilt place in the world,” the realtor said. (Hill would have dismissed such claims; he, unbelievably, called it “a plain substantial affair.”) The original bank-sized vault is still on the ground floor. On the top floor is a marble fireplace taken from the home of Louis XIV; above it is a large flat-screen television and across the room is a hot tub with an almost 180-degree view of Lake Union snaking out under bridges and the white, bony masts of sailboats on Puget Sound.

Like Maryhill, the Seattle mansion was intended for Hill’s family, but they didn’t live there. His wife and children returned to their native Minnesota less than a year after they came to Seattle, and the marriage seemed to disappear into thin air. No records explain why. But Hill kept making buildings that he hoped would be family homes, as if the appearance of familyhood erected in a material as strong as concrete might will the real thing into existence. Hill had three illegitimate children with three other women, at least one of whom he put up very comfortably, but never in his family homes. They were for the family that wasn’t.

The homes were also for protection, protection Hill never needed. He was afraid of attackers: German, Russian, or Japanese, depending on the period. From his lonely bedroom in Seattle, he had a switch that turned on all the lights in the mansion at once. If this place was an unspoken fortress for him, Maryhill was the real fortress, a place where the thick roof could be packed with heavy artillery in order to defend the country’s borders. He announced this intention publicly, although a location that far inland would never be of use. (No wonder the locals called Maryhill “Sam Hill’s Folly.”) Hill’s ostensible reason for building the mansion in Seattle, aside from sheltering his family, was “to help the town entertain the Crown Prince of Belgium on his visit here to the Exposition, that’s all—just to help out,” as he told the Seattle Daily Times in August 1909. That was another disaster: the prince didn’t make it, “because of complications in the Congo,” as Hill told the newspaper. The evidence of this disappointment and the elaborate buildup to the royal visit remains carved into the building: small holes in rows all the way up the sides of the facade denote the places where Hill attached the ivy plant that he cut down from an overgrown lean-to in the Cascade Mountains, hauled into Seattle, and planted in a moat of soil he had dug around the mansion for the occasion. He needed his mansion, after all, to look like it had been there, growing ivy, for a hundred years or more, like a proper aristocratic home—not something newly built by a wheedling American. No wonder he never felt at home there. Instead of staying at the mansion when he was in Seattle, he often took up residence at a local gentlemen’s club for no reason at all. His home was on the road, on the go, making things happen, driven perpetually by the fact that his failures were almost exactly equal to his successes. He must always have felt that the next thing would be the thing.6 He died in Portland, Oregon, in the middle of a business trip.

What Hill couldn’t do that Han and Mihalyo did was let go. They happily built scaffolding that wouldn’t ever become a building. They put up a rejected architectural plan. That’s not to say it was easy; they slept lightly the whole run. Winds up to fifty miles per hour slapped at the visitors, some of whom made the dangerous choice to walk the flimsy planks around the top. There were no signs; like Hill and Han and Mihalyo, you had to make your own decisions about how to behave in this wild place. An eighty-nine-year-old woman with a cane went all the way up the stairs. Children monkey-barred from great heights. A 150-foot black dust devil rose from near the rattlesnake Dumpsters one day, swept across the short distance to where the artists were sitting to welcome visitors, and ripped the roof off the welcome hut as locals continued to chat nonchalantly. One night, 5,700 lightning strikes hit the area. Visitors experienced something like Stendhal Syndrome, telling the artists things like “I really get it” and “This changed my life.” The artists didn’t ask for elaboration. On the last day of the installation, October 1, visitors started coming at sunrise, and they formed a steady stream all day. Shots rang out and a man walked by, pushing a bloody deer in a wheelbarrow: it was the first day of hunting season, and the artists were tired and ready to leave.

The Double was three years in the making and three months standing. Dismantling it took three days. The artists climbed the scaffolding and cut the roughly eight thousand zip ties that attached the netting, one by one. They didn’t try to catch the ties or the blue fabric. Instead, they made their cuts and leaned back, letting the wind carry each piece up to one hundred feet until it dropped to the ground, like the Double was exploding in slow motion. Then they took down the scaffolding, gathered everything up, and drove away.

For a few summers, the artists plan to return to see the worn grass, to remember the Double like an animal that sat there for a while and then ambled off. Eventually, even that will be gone. All that will be left is Maryhill, asleep again.