The last published novel of Gilbert Sorrentino—his twentieth, though the math is complicated by his constant rejiggering of what, exactly, constitutes a novel—initially appeared to be A Strange Commonplace, published in 2006, shortly before his death. Nonetheless, the following year, the online magazine Golden Handcuffs Review ran the equivalent of eight or ten pages from a subsequent longer work. The author’s son Christopher (himself a novelist) arranged for the publication of this longer work with his father’s last publisher, Coffee House Press (to be released next month), and added an opening note, sharp yet moving, which claims that the book was finished, its final adjustments made by his father’s hand.

The Abyss of Human Illusion is an assemblage of prose shards, none longer than four or five paragraphs, each refracting some small light into another corner of Sorrentino’s imaginative homeland, the beaten-down working class of mid-twentieth-century Brooklyn. Yet Abyss resists easy characterization as urban realism, since each entry closes with a “commentary,” much of which is quite funny, masterfully spinning through rhetoric high and low: “He was no better, no cleverer, no more insightful than any shuffling old bastard in the street, absurdly bundled against the slightest breeze.” Gallows humor pervades the whole; an old writer, unnamed, laments the fraudulence of his calling. Like everyone here, he’s “left a lot of wreckage behind.”

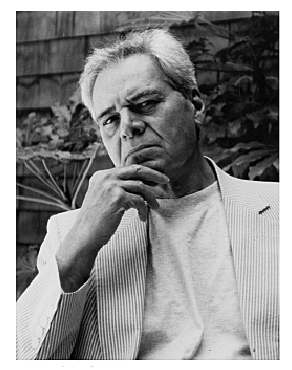

Gilbert Sorrentino dedicated a career to an assault on expectation. In some cases he attacked head-on: few other serious authors savaged, with such ferocious energy, the publishing industry. As early as 1971, referring to mid-Manhattan’s Powers That Be in Imaginative Qualities of Actual Things, he sneered, “You could die laughing,” and he went on dying in print for another thirty-five years. Nor was he reluctant to bite the other hand that fed him. Though he taught for twenty years at Stanford, his “Gala Cocktail Party” from Blue Pastoral (1983) was a brilliant skewering of academy phoniness.

In an essay on William Carlos Williams—his enduring inspiration—Sorrentino insists, “America eats her artists alive.” That is, the culture celebrates creative spirits who produce “trash.” “Writing is most admired when it is decorously resting… the more comatose, the more static a mirror image of ‘reality’ the better.” So the great majority of his countrymen “employ language and techniques inadequate” to the times, creating drama via hand-me-down emotional signals, interactions across “a sea of manners.” In the work of John Updike, to name one of his bêtes noires, catharsis was nothing but a papier maché of chewed-up and regurgitated convention: trash. Such contrariness finds its most direct expression, naturally, in Sorrentino’s essay collection Something Said, first published in 1984 (expanded and reissued in 2001). Getting beyond the sham that passes for represented reality also animates his dozen books of poetry—the best perhaps Corrosive Sublimate (1971)—as well as the stories collected in The Moon in Its Flight (2004, though a number had been anthologized elsewhere).

This innovative novelist never suggests, however, that a reading experience of two hundred pages or so can rely entirely on formal qualities. Well-turned phrases certainly please Sorrentino, but he recognizes as well that a book-length work in a language-based art form can’t help but engage the passions. His rave review for William Gaddis’s JR bears a title that’s all about the passions: “Lost Lives.” His complaint about the common run of contemporary novels lies elsewhere, in the notion that they perform a laughable emotional charade, as dated as the Gibson girls that decorate a creaky carnival ride (to borrow a pertinent metaphor from John Barth’s “Lost in the Funhouse”). All right, then—what does Sorrentino offer instead? Does his work construct a new apparatus for finding what hurts and making us share it?

*

Born in 1929, the product of immigrant Brooklyn factory workers, Sorrentino studied the literature of the English Renaissance, before and after a stint in the army. He never earned a degree, however, and he’s best appreciated as an autodidact who served a remarkable apprenticeship in New York, amid “an incredible artistic ferment” (to quote from a 2001 article in the Review of Contemporary Fiction). A jazz buff and a regular at the Cedar Tavern (famed hangout of the abstract expressionists), Sorrentino moved in cutting-edge circles that included, by the end of the 1950s, both Williams and the other figure with whom he’s most closely identified, Hubert Selby, Jr. Sorrentino helped edit two avant-garde magazines, Neon (where Selby was co-editor) and Kulchur. His first collection of poetry appeared in 1960, and his debut novel, The Sky Changes, in 1966.

Though Sorrentino made revisions for a new edition twenty years later, from the first The Sky Changes was notable for its striking word combinations, coarse yet subtle, extending deep sympathy yet casting a cold eye: “They had another drink, and C told him how happy he was that his wife and P had finally decided to make it together, because he was good for the kids, and the husband agreed. So they lied warmly to each other and their friendship resumed where insanity and despair had cut it off.” Changes does without full names or direct quotation, while also toying with chronology and authorial intrusion. Nevertheless, the novel presents a recognizable crisis: a divorce story.

In 1970 and ’71 the author came out with Steelwork and Imaginative Qualities of Actual Things. Both novels establish the mode at which Sorrentino excelled: the portrait of a miserable community, from which he fillets any trace of bathos with deft cuts of hilarity and frankness. Also helping defeat sentimentality are the disrupted chronology and the absence of any central narrative. Both novels achieve the equilibrium of a great bebop workout, in which every fresh racket loops back eventually to the head. Not for nothing does Steelwork begin with the Charlie Parker rave-up, “KoKo,” its “great blasts of foreign air” disrupting the afternoon of two young men in Brooklyn, 1945.

Brooklyn, to be sure. Sorrentino’s writing would seem autobiographical if his work weren’t so discontinuous, the solos of Steelwork scattered across fifteen years of depression and war and amid half a hundred players (though Gibby and others occasionally recur). A more fitting model than the bildungsroman is the American immigrant tragedy, the stuff of Henry Roth, since for Sorrentino’s people pulling yourself up by your bootstraps only exposes you to worse punishment. But then Imaginative Qualities of Actual Things rejects even that typology, as it crosses the river to join the turn-of-the-’60s Manhattan art world, where everyone’s on a budget and most people prove to be frauds. Here Sorrentino works with a smaller group and a central consciousness, an unnamed narrator spinning the loose-limbed anecdotes. This author figure fully comprehends what a bunch of losers he’s got as friends (even before they begin to betray each other). He needs only a single paragraph from an old letter to realize that a member of the group, the short-story writer Guy, has genuine talent. But the narrator sees as well that Guy’s a tormented closet case, without the spine to stand up to the nabobs of publishing.

In both novels, Sorrentino interpolates all sorts of borrowed language into his natural poetic intensity. Sentences wiggle in and out of journalese, advertising jargon, ethnic slurs, whiskey blather, and the sweet nothings of loveless sex. The shreds in the latter novel’s patchwork tend to be more colorful, the combinations more gleeful, a difference implied in the titles. Imaginative Qualities of Actual Things comes from Williams’s Kora in Hell, and in the novel Sorrentino repeatedly references the earlier poet’s famed passage from “To Elsie”: “It is only in isolate flecks that / something / is given off.” Indeed, those lines might speak for everything Sorrentino wrote, though he would tap his old mentor for a title only once more, in his penultimate work, Strange Commonplace.

“To Elsie” is, among other things, a miracle of empathy. Williams gives expression to a reality far more brutish than his own. So, too, do Sorrentino’s novels of ’70 and ’71 consistently forge a wincing connection with their battered inhabitants. The work moves us to pity and terror, no less—Imaginative Qualities especially, though none of the wannabes who populate the book possess what Aristotle would call “tragic stature.” A signal case occurs when the omniscient storyteller struggles to make sense of Bunny, a pretty hanger-on, briefly and brainlessly married to Guy:

It would’ve been better had I simply not got involved with Bunny, she’s hopeless. I’ll bet you a dollar that she gets a job in a publishing house assisting a hip young editor…. She’s one of those bright, lovely, intelligent people who should never have been born. We’ll finish with her postmarital career by putting her in a Connecticut motel one December afternoon, with a gang of young, creative professionals, half-drunk. She’s in the middle of a laugh, those perfect white teeth. They’re all watching the Giant game. Bunny, who is now called Jo, suddenly recalls Guy’s absolute contempt for football: “For morons who like pain.” She looks around at her friends and hands her empty glass, smiling, to her escort. Her heart a chunk of burning metal. She will marry this man.

The scene, in narrative terms, comes out of nowhere and goes nowhere. We never again encounter these young creative morons. Yet within the fiction’s abstract-expressionist whole, the moment’s a climax, its agony piercing. And within the career of the author, this pair of novels presents a creative peak.

Fifteen books followed, none of them much resembling what E.M. Forster would call a novel, but a good two or three often mentioned as Sorrentino’s greatest. Chief among those would be his next big project, Mulligan Stew (1979). His longest stand-alone work at nearly 450 pages, the novel afforded Sorrentino his lone brush with wider recognition, in part because the means of publication courted controversy. The book appeared from Grove Press, where Sorrentino had been employed, and the text was prefaced by rejection letters the manuscript had received elsewhere (names changed, but thickheadedness left untouched). Reviewers, predictably, couldn’t resist, and most were respectful. Almost thirty years following its publication, in a brusque New York Times obituary, the only Sorrentino book mentioned by name was this one. Mulligan Stew is also the lone title that Frederick Karl examined in his critical omnibus American Fictions 1940–1980. Karl’s response was mixed, but not when it came to the novel’s madcap lists. He understood the usefulness of this device, first indulged in Steelwork but exploited to the hilt in Stew: here enumerating the clutter of an old barn, there the inventory of mail-order sexual aids.

In Mulligan Stew, Sorrentino presents a classic metamorphosis, in which the novelist Tony Lamont declines into madness while his characters attain freedom and power. In a more ordinary Big Book, the reversal would take the shape of mounting tensions and dramatic confrontations, but this one embodies the breakdown of “lonely, lonely Lamont,” by and large, with lengthy rounds of parody. The lists function as part of the comedy. They free the man behind Lamont from the sort of narration he finds counterfeit and embalmed, even as they send him into verbal performances not unlike those found in a conventional climax. The novel closes with just such a bang, six pages of gifts (all to people never mentioned previously)—tokens, perhaps, for Lamont’s parting: “To Helena Walsh, the goatish glance of the cockeyed lecher; to Twisty Abe DeHarvarde, shimmering hose of glittering glows….”

Astonishing lists, and though Frederick Karl grasped their purpose, he found other elements of Stew disappointing, even “unimaginative.” The tangle of underappreciated authors, invented and actual, wore him out, as did all the “fraternity-house male-female antics.” Such misgivings, from our present perspective, seem right. Sorrentino isn’t comfortable spending so long with just one character, and his comic games, for all their brilliance, start to feel like mere nervous distraction—especially compared to the emotional impact of the novel that followed, Aberration of Starlight.

What’s impressive about this gloomy little masterpiece isn’t so much that it was published by Random House with a blurb from Philip Roth, or that it made the short list for the 1980 PEN/Faulkner Award. What stands out is its very nearly straightforward realism. The prose is as flexible as ever, but within careful restraints: the present action occupies a single weekend in New Jersey, and the voices, both interior and spoken, are those of a few New York wage slaves at a cheap resort. It’s the end of summer 1939, and a Holocaust looms for these people as well, though Aberration generates suspense not with war stories but via a literary experiment—its devastation coheres only as we work through four successive points of view. Their order contains the inevitability of aging: first a boy, then his divorced mother, then her Saturday-night seducer, and finally the boy’s grandfather. The brief spate of pornography feels apropos, unlike in the previous novel, as the character enjoying the fantasy is a salesman on the road. As for the actual sex, it may be the most fully rendered in Sorrentino’s oeuvre, though unhappy and deluded: “She was covering herself up too, smoothing her dress.… ‘I love you,’ he whispered, and they kissed again, chastely, but… [h]e wasn’t complaining, hell no. A hand job from a doll who’s almost a nun on the first date? Tom had no beef, kiddo.”

For the author, what mattered proved to be the experiment. Over the next twenty years, Sorrentino’s prose not only embraced radical alternatives to plot, but also eschewed character tensions or other sources of empathy. Granted, he’d always flirted with such extremes. Between Imaginative Qualities and Stew, in fact, he brought out the pamphlet-sized Splendide-Hôtel (1973), an emphatic rejection of story and mimesis, its form based on the alphabet. Hôtel has a satisfying zaniness, but Sorrentino took his recreation far further throughout the ’80s and ’90s. With all due respect for Robert Coover (who was more respectful about narrative) or Kathy Acker (who was more of a social critic), it’s fair to say that, starting with Crystal Vision in ’81, Sorrentino subverted expectations for fiction more thoroughly than any American writer of his stature. By 1997, the late philosopher-critic Louis Mackey (himself a boundary-blurring figure, with cameos in two Richard Linklater movies) claimed that Sorrentino had brought off “the ultimate postmodern novel.”

In Fact, Fiction, and Representation: Four Novels by Gilbert Sorrentino, Mackey provides an exegesis of the ’80s threesome Odd Number, Rose Theater, and Misterioso, and he argues that these small- and smaller-press publications amount to the “culmination” of the author’s project. The novels have since been repackaged by Dalkey Archive as the opus Pack of Lies (Dalkey keeps most of Sorrentino’s work in print). These scattered shards of a murder mystery prove delightful at the level of the sentence, full of panache in a breathtaking variety of tonal hues. Any number of passages set you laughing aloud, and comedy is part of the trilogy’s raison d’être, given how Sorrentino’s downbeat vision tended to constrain him whenever he worked in a realistic mode. But it’s comedy without humanity, and as a whole has a sterile affect. The sexual hijinks never involve actual people, but rather mere names, often recycled from earlier books. An attentive reader may detect traces of coherence, but it takes an acolyte like Mackey to divine each fiction’s organizing principle. The climactic Misterioso is nothing so inviting as the eponymous Thelonious Monk tune. It’s arranged according to an obscure seventeenth-century catalogue of demons, their names and others’ worked into a double-alphabet, one proceeding backwards and the other forwards.

Pack of Lies does amount to a culmination, but one of baroque idiosyncrasy. For my money, the more rewarding distillation of this author’s sensibility came a few years later, in his last three-pack of book-length prose preceding Abyss. Little Casino appeared in 2002 and Lunar Follies in 2005, followed by A Strange Commonplace. Each seems a legitimate candidate for that hard-to-determine honor, the Best of Sorrentino. Little Casino returned him to the PEN/Faulkner short list, and on first reading Follies and Commonplace may pack an even greater wallop. What distinguishes these last books is their reassertion of an emotional content, even in fictional constructs that have no truck with convention.

Each exhibits great skill at stylistic modulation, but none indulge the excesses of Stew or Lies. Each presents a plot-surrogate at once sophisticated and apprehensible, so the reading delivers that central pleasure of a text—perceiving and completing a whole. Overall, this tireless innovator opens himself anew, four decades into the vocation, to the passions engaged by an art made of words. Sorrentino’s final work remains prickly about those passions, to be sure, but it nonetheless reveals a respect for how the best prose can embody what we call insight. In Abyss, the unnamed old writer can’t quit writing, despite his sober awareness that his work “proved nothing, changed nothing, and spoke to about as many people as one could fit into a small movie theater.” Still, he continues “to blunder… until finally, perhaps, he would get said what could never be said.”

Before I blunder myself, turning too warm and fuzzy, I need to test my ideas against Lunar Follies. If I mean to say that in his final novels Sorrentino recommitted to something like opening a window on the soul (the very idea!), then this effort from ’05 presents my steepest challenge. As the title implies, the book is out there. Plot, protagonists, and chronology are nowhere to be found. Casino and Commonplace at least revisit the broken families of mid-century New York. No one emerges as dramatis personae, as meager lives undergo biopsies of two and three pages each, but nonetheless we visitors share their suffering. In particular, A Strange Commonplace brims with personality, its plans for suicide and its dream passages genuinely haunting; the novel makes a lovely valediction. But Lunar Follies hardly has people in it at all.

The book collects trash, actually—the kind of thing Sorrentino spent a lifetime warring against. The “folly” here refers to the detritus of the art world, as Sorrentino dreams up catalogue copy for exhibits beneath contempt, as well as numbskull reviews, trash gossip, and so on. There’s also an academic deconstruction, hopelessly clotted. Stranger still, each “chapter” (or whatever you’d call it) is titled with the name of some lunar landmark, fifty-three mountains and seas arranged alphabetically. From the first page, “It’s on to the snow-chains story; the heat-wave story; the story of the tough coach and his swell young protégé; the killer-hurricane (with puppy) story…”—it’s on, that is, to brief but scorching rounds of parody. One piece of poshlost after another, the book exposes the con games that can poison a life in the arts. The jokes, however, cluster and explode quickly, and in contexts easy to grasp; as Sorrentino’s moon illuminates his detested “sea of manners,” it’s more satire than parody, and invites participation. Likewise, though the book is densely intertextual (as one might expect given the subject), a reader doesn’t need to catch all the isolate flecks to appreciate the fun or see the system. Consider, for instance, the list of personalities in what appears to be a photography exhibit titled “Our Neighbors, the Italians”:

Familiar Carmine, who cursed out a Puerto Rican mother, hey, why not, they breed like animals.

… Benign Giannino, who once read a book for fun.

Garish Richie, who has a mouth he shoulda gone to law school.

Exuberant Frankie Hips, who don’t mind moolanyans if they mind their fuckin’ business.

No-nonsense Gil Sorrentino, who worked a dig at ethnic solidarity into nearly every one of his books. Wisecracking Sorrentino, who was rarely so eager to have you follow his snarling tune. Yet it’s the structure rather than the rhetoric of Follies that demonstrates how Sorrentino developed a new apparatus for catharsis (or at least one that’s rarely been so well-used). Most of the book’s longer pieces occupy the passages named after those wide-open spaces called the moon’s seas, and since these start with the letter S, the novel reaches a kind of climax with some of its most complex entries. With some of its least comical, too, for entries like “Sea of Moisture” and “Sea of Tranquillity” offer little or no satire. Rather, they cast shadows of mortality over whatever project they’re concerned with, and so create—of all things—an epiphany, a pang of insight and identification. The “sea” chapters dramatize how paltry is the gain, just a few bucks or a few strokes, from even the oiliest con. They assert, with Flaubert, that of all lies, art is the least untrue.

To argue that Gilbert Sorrentino’s book-length prose was ultimately about what’s true might seem a dubious exercise. To him, the T-word was a signifier long perverted by abuse, and so he constructed his novels to enlarge the field of discourse, to put as much distance as he could between himself and that abuse. Maybe, by dint of that wide-ranging exploration, he also located some fresh ground where once again truth could be itself, vulnerable and volatile. That’s my contention, anyway: that this author came back home now and then, and when he did he found it a place of greater power and durability precisely because he’d first traveled on so far an odyssey.