“The entire world we live in is fabricated.”

—Guillermo del Toro, in an interview with Terry Gross

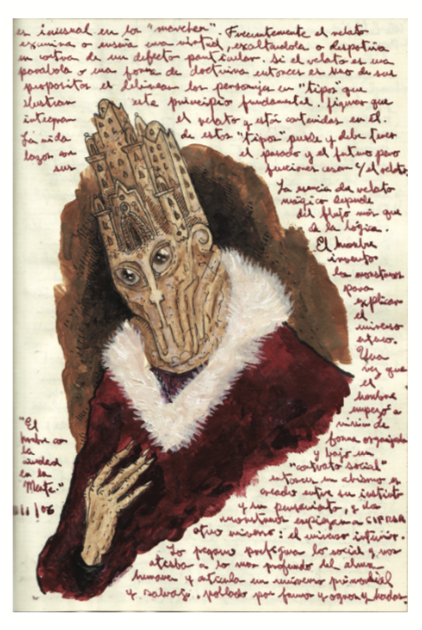

Among the dizzying array of grotesque entities crowding our vision in the Troll Market scene in Hellboy II, a creature in a red velvet fur-trimmed robe flashes briefly across the screen. Over its simian eyes and muzzle sits a miniature cathedral, complete with double towers and decorated archivolts, where a forehead should be. “Originally the idea was to have little humans running around the ramparts,” this creature’s onlie begetter, the movie’s writer/director Guillermo del Toro, cheerfully reported. “But the budget wouldn’t allow it.”

One of about thirty “throwaway” creatures del Toro created for a bravura tableau clearly intended to trump the cantina scene of George Lucas’s first Star Wars film, the monster called Cathedral Head is an emblem of its creator in much the same way the Troll Market sums up the manic whirlwind of a story it’s embedded in. Hellboy II, cowritten, like the first installment, with Mike Mignola from the latter’s graphic-novel series (and aptly dubbed “Pan’s Labyrinth on speed” by one of its producers), expands del Toro’s distinctive vocabulary of images in a baroque explosion of forms commemorated in a coffee-table book, Hellboy II: The Art of the Movie, published to coincide with the film’s release on DVD.

Currently del Toro is contractually committed to a two-movie version of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit; remakes of Frankenstein; Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde; and Slaughterhouse-Five; an adaptation of H. P. Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness that he has already drafted a screenplay for; a three-volume vampire novel; and assorted other screenplays and producing gigs. As the forty-four-year-old director embarks on this staggeringly ambitious slate of projects that will keep him busy through the year 2017, it’s instructive to take a closer look at the deeply Gothic worldview that informs his work.

What, exactly, is Gothic? In recent decades the word has been stretched thinner than the cosmetic-surgery addict’s facial skin in Terry Gilliam’s Brazil, but historically it describes two separate categories:

(1) What I like to call “Gothick,” the post-Enlightenment popular entertainments (bookended by Horace Walpole’s 1764 The Castle of Otranto and Charles Maturin’s Melmoth the Wanderer in 1820) that have morphed, through Victorian ghost stories and early twentieth-century pulp and comic-book horror, into today’s plethora of subgenres, including film, video games, “lifestyles,” and even new religious movements, and

(2) The actual historical period of the European Middle Ages, first dubbed “Gothic” (a word redolent of nasty barbarian Huns) by Renaissance architects anxious to distinguish their own work, inspired by Greek and Roman antiquity, from medieval sacred architecture. By the time of Walpole and his successors, it was a catchall label for a heady, nostalgic brew of decorative medievalisms served up in melodramatic novels and plays featuring illicit passion, secret crimes, nefarious Roman Catholic clerics, all folded into the suffocating embrace of an ancient abbey or ancestral home.

Del Toro’s films uniquely mix the old Gothic and the (relatively new) Gothick. Born and raised in Guadalajara, Mexico, he has often described his childhood infatuation with monsters and the scandalized reaction of his devout grandmother, who twice attempted to perform exorcisms on him. “It’s a spiritual reality as strong as when people say, ‘I accept Jesus in my heart.’ Well, at a certain age, I accepted monsters into my heart.” In his brilliant commentary track to the 2004 special-edition DVD of The Devil’s Backbone (2001), he defines the Gothick as a way of seeing that discovers beauty in the monstrous. Because it “celebrates, embraces, and cherishes the darkness” we’ve been raised to reject, he asserts, the Gothick is the “only genre that teaches us to understand otherness.” Of Hellboy II he has said: “I find monstrous things incredibly beautiful, in the way that the most beautiful carvings in Gothic cathedrals are the grotesque carvings. If I were a mason, I would be carving gargoyles.”

Del Toro’s insistence that the monstrous is sacred is closer to the spirit of premodern Catholic Europe than his grandmother may have realized. Medieval Christianity embraced a more inclusive vision than post-Reformation and Counter-Reformation Protestants or Catholics do. “There are monsters side by side with angels in cathedrals for a reason,” del Toro explained to David Cohen in a Variety interview. “They occupy the same parcel in the imagination of mankind that angels occupy.” One thinks, for instance, of the virgin martyr Saint Wilgefortis, who miraculously grew a beard to protest her marriage to a pagan king and was promptly crucified by her father. Depicted as a bearded hermaphrodite on a cross—in effect, a seditious female Christ—Wilgefortis became the very popular patron saint of monsters in the fifteenth century.

To create his distinctive production designs, del Toro draws from a wide palette, including old-Gothic architecture; Piranesi; the symbolists Arnold Böcklin, Caspar David Friedrich, and Odilon Redon (there’s also a nod, of course, to Christina Rossetti in the “Troll Market” conceit); and the surrealists. His monsters, however, follow the aesthetic conventions of video-gaming creature design and the Hollywood horror-movie canon. As a child, he reports, he gave his heart equally to comic books and art books. This joyful mixing of high- and lowbrow shows the same all-embracing sensibility we find in medieval illuminated manuscripts, where the margins of devotional texts display, among other images, tiny nuns carrying bowls of turds and men defecating eggs. Del Toro also references the Mexican folk tradition of alejibres, made-up creatures drawn from the individual artisan’s own imagination, styling his movies “my personal bestiaries of fanciful creatures.” But medieval bestiaries, he stresses, were also important for their “cosmological, symbolic, and spiritual meanings,” and he wants his creatures to carry this deeper significance.

To understand what these spiritual meanings were, we need to look at the worldview shared by Westerners of the Middle Ages. People of this era saw themselves situated inside concentric dimensions of reality within which they, their dwellings, their villages and cities, and all the plants, animals, and natural landscapes around them were little worlds that imperfectly mirrored the attributes of the larger immortal world and also drew down its wrath or blessings. This top-down relationship between the eternal realm and our finite material lives is summed up in a well-known dictum of medieval alchemy, “As above, so below.”

In the old-Gothic way of seeing things, our natures down here, our little worlds, rub up against and resonate with all the other little worlds around us and the world above. A person’s defects or evil acts can show up in withered crops and lightning from the heavens. Robert Bly comes close to capturing the animistic spirit of this worldview in his poem “My Father’s Wedding”:

[…] If a man, cautious,

hides his limp,

somebody has to limp it. Things

do it; the surroundings limp.

House walls get scars,

the car breaks down; matter, in drudgery, takes it up.

The difference between Bly’s modern perspective, which is human-centric and psychological, and that of a person of the European Middle Ages is that for an old Goth, a limp down here on Earth doesn’t necessarily produce all the others. Rather, everything limps by virtue of an acausal principle emanating from a higher level of reality that modern Westerners call synchronicity and our cultural ancestors called the law of correspondences. In this scheme, all things in the physical world are bound up in an invisible web of influences ruled by forces in that other dimension outside time and space.

These old-Gothic notions insinuate themselves in the Gothick terrain of del Toro’s films. The Devil’s Backbone, a ghost story set in a remote orphanage during the Spanish Civil War, seems at first glance to be a classic Gothick romance, which, as del Toro reminds us in his commentary, focuses on the house, the domicile, as an emblem and warped container of the human self. This symbolically charged structure, he says, always conceals a “dark secret,” linked to a treasure and deep passions, “that is buried in the past and affects the people living in it.” At the center of the darkness stands “a very pure hero—a new set of eyes to explore the secret and through the purity of his heart unravel the mystery.”

Looming over a desert wasteland much like the palace of the dead in Herk Harvey’s 1962 Carnival of Souls, the orphanage does conceal a secret (the murder of one of its young charges), along with thwarted love and a hidden treasure in gold ingots. The opening scene frames the imposing structure’s empty entrance: an unknown voice (that, we later learn, of its dead physician) asks, “Qué es una fantasma?” (What is a ghost?) as the newly orphaned Carlos, the pure soul of The Devil’s Backbone, arrives at its gates by car. As the story unfolds, the deceased doctor’s rhetorical question frames our sense that all the characters, living and dead, are imprisoned in this edifice, “frozen in time” like “insects in amber,” a key del Toro image.

But when an enormous bomb lands in the orphanage courtyard immediately after a child’s death, our minds connect these two events not by the genre conventions of Gothick storytelling but rather by the folkloric logic of the old worldview. The two acts have no cause-and-effect connection; what they do is resonate with each other’s violence. “Like the best fairy tales of my childhood,” del Toro says, “what’s inside the castle reflects what’s outside.” The bomb—a nod, the director tells us, to the enigmatic giant’s helmet that drops out of the sky to land in a castle courtyard at the beginning of The Castle of Otranto—never explodes, but “all the characters will reenact the savage nature of the war within the [orphanage’s] walls,” and the child’s ghost will penetrate the material realm to exact vengeance.

In del Toro’s awards-laden Pan’s Labyrinth (more precisely, El Laberinto del fauno, “The Faun’s Labyrinth”), also set during the Spanish Civil War, the pure hero is the young girl Ofelia—a name resonant with doomed maidens who return to the elements—and the orphanage is replaced by a rural mill deep in a forest in northern Spain where Ofelia’s evil stepfather, one Captain Vidal of Franco’s army, has established his headquarters to fight the last-ditch post–Civil War Republican guerrillas. Del Toro has described this film—and it was interpreted by critics, and received by international audiences—as a political parable about the Spanish Civil War. From this perspective, its fantastic elements (a faun, fairies, other denizens of a supernatural underworld to which the main character seems to return upon her death) are either figments of the young heroine’s imagination or simply a secondary set of metaphors for the violent events that unfold in the story’s “real” world. The essence of Pan’s Labyrinth, however, lies more in medieval metaphysics than modern politics. The fairy-tale characters are deliberately unshaded; the politics are black and white. And because del Toro devised the story himself, it’s a key—a golden key—to his old-Gothic/Gothick personal mythos.

Pan’s Labyrinth begins literally in darkness with the labored breathing of the dying Ofelia. She is lying inside the old stone labyrinth behind the mill, at the edge of a hole in the earth that, we will learn, is the last open portal to the underworld. As in The Devil’s Backbone, an unknown supernatural voice (in this case, the Faun’s) speaks first, this time the familiar words that open a fairy tale: Once upon a time, he says, the great Princess Moanna came to live among humans and forgot she was an immortal being. As the camera closes on Ofelia’s open eye, the blood running from her nose reverses its flow, a startling antirealist signal that the story is moving into a flashback.

After this quick opening frame, incomprehensible until the movie’s end, the story begins with Ofelia’s own journey by car with her pregnant mother to join Captain Vidal in the country. Ofelia discovers a carved stone eye by the wooded roadside and reinserts it into the crudely carved trailside stela of a faunlike creature, an act that seems to animate two magical flying stick bugs, who follow the entourage to the old mill.

Del Toro’s choice of a mill as this story’s dysfunctional Gothick house of self also reminds us that in the old fairy tales millers are tricky characters who sell their daughters to the devil—and that in myth and folklore generally, the demonic is often represented by mechanical, endlessly repeating movement that never reaches completion (think Tantalus and Sisyphus). The mill’s ancient cog-and-wheel innards, visible in the room where Captain Vidal is camped, are equivalent to the mechanism of the watch he obsessively rewinds, endlessly resuscitating it from mechanical death. The watch’s cracked face in turn not only is equivalent to the Captain’s fractured personality—note that the old-Gothic worldview does not recognize “symbols” or “metaphors,” only equivalents operating at different levels of reality—but also serves as a kind of tombstone for his father, a general who deliberately smashed it as he fell in battle in Morocco so that his son would know the exact moment of his death.

Like all things mechanical in a del Toro movie, the Captain’s watch exerts an irresistible fascination even as it also carries the negative charge of unredeemed repetition-compulsion that is the dark side of the underworld. In the same vein, the centerpiece of del Toro’s first movie, Cronos (1993), was a cog-and-wheel clockwork device made of gold that houses a magical insect whose bite inoculates victims with its own blood, bestowing eternal life and a vampiric need to drink the blood of others.

The dark secret of the classic Gothick story is often found underground, in the basement or crypt of the house/human psyche, but in del Toro’s universe the region belowground always opens onto another dimension, the old-Gothic supernatural reality of the underworld. In The Devil’s Backbone, this is the vaulted cellar of the orphanage haunted by the ghost of Santi, the murdered child. The underworld of Pan’s Labyrinth is located beneath the old stone maze behind the mill, a site Ofelia is immediately drawn to. At the center of this ancient labyrinth, itself an emblem of immortality, she finds a dried-up stone well with a winding staircase inside that she follows to the bottom. Here Ofelia encounters a fantastical man-goat, the Faun, who eagerly welcomes her home as “Princess Moanna” and instructs her in three tasks she must complete to regain her status as an immortal.

Beyond the Faun’s antechamber, the underworld of Pan’s Labyrinth unfolds as a series of vaulted old-Gothic corridors and chambers suffused in a womblike red-gold aura. This warmly lit space is a sharp departure from the Gothick urban grottos and crypts that served as del Toro’s underworlds in his earlier movies Mimic (1997), Blade II (2002), and Hellboy (2004). In Mimic (a film removed from the director’s full control), giant man-eating mutated insects and humans mirror each other in manifold ways in abandoned tunnels of the New York subway, where the dripping stalactites that are the insects’ enormous turds hang from rusted-out subway machinery, making this subterranean grotto as anal as the Pan’s Labyrinth underworld is uterine. The opening portal to the underworld in the first Hellboy is located in that Gothick staple, a ruined abbey in Scotland, but del Toro’s trademark juxtaposition of uncanny organic with uncanny inorganic plays out more fully in the underworld beneath the reanimated monk Rasputin’s tomb, a Piranesian nightmare where formidable death-dealing, perpetually wheeling mechanical devices are paired with tentacled Lovecraftian entities who seek domination of our world.

More than any other element of the old-Gothic worldview, however, the imagery of the medieval science of alchemy permeates del Toro’s films. The frame story of Cronos concerns a sixteenth-century alchemist (probably modeled on Nicholas Flamel) who turns into a vampire to sustain his eternal life. Also running through all his work is the pervasive image of the fetus in a glass jar—referencing the famous homunculus, a microcosmic “little man,” transformed within the vessel into a bringer of new life and possibilities. As in Cronos, the alchemical crucible of The Devil’s Backbone imprisons rather than transforms: the impotent Dr. Casares pickles embryos deformed by spina bifida (the “devil’s backbone” of the title) in liquid that he bottles and peddles in town as an aphrodisiac. Far from carrying hope of a new life, in the universe of this story the dead babies are equivalent to (again, as distinct from metaphors for) the lost souls, adults and children, trapped in the orphanage along with the children. These broken characters are the product of a human development process that del Toro has vividly compared to that of the deformed beggars of Victor Hugo’s The Man Who Laughs, grown inside jars as babies by human traffickers. “I think that’s what the world does to kids,” he said to an Australian interviewer. “You are born into your family jar and you grow into the shape of it, and the rest of your life you are limping like a motherfucker.”

Pan’s Labyrinth leavens this Gothick darkness with the brighter atmosphere of fairy tales that is closer to the old-Gothic spirit. According to the laws of spiritual alchemy, an alchemist can transform materials in the world outside him—turn lead into gold, find the lapis or philosopher’s stone—only if he is working on a similar moral transformation inside himself. The prime alchemist in Pan’s Labyrinth proves to be Ofelia herself, and most of the transformations in both worlds, material and supernatural, mirror her own moral development toward goodness. When she first encounters the stick bugs, the enchanted world is in as much disarray as the human one; it is, in del Toro’s words, “a magical universe that’s been left out in the rain too long.” It starts to change for the better, however, as soon as the former immortal enters the picture; the stick bugs morph into Victorian sprites after Ofelia asks them if they are fairies like the pictures in her storybook. Though mainstream audiences are quick to interpret this transformation as Ofelia’s own make-believe fantasy, it can also indicate that she has already gained the magical ability to change objects in her surroundings simply by focusing her awareness on them.

Performing the three tasks brings more of the same kind of benefits. When Ofelia retrieves the golden key from an enormous toad who vomits up his whole body inside out, she is following the alchemical principle of in stercore invenitur, finding physical and spiritual treasure in the least likely place via the attraction of opposites.

The line between inside and outside, ordinary life and the supernatural, blurs as the two realms of Pan’s Labyrinth, the real world and the underworld, begin to mirror and alchemically transform each other. The Faun gives Ofelia a mandrake-root homunculus that comes to life as a plant-baby when Ofelia bathes it in milk. The mandrake-root baby’s exuberant health calms its coequal, the unquiet baby in Ofelia’s mother’s womb. But when the Captain discovers the root and throws it into the fireplace, the healing link between the two congruent life forms is broken and Ofelia’s baby brother bursts out in a murderous rush, killing his mother.

Roger Ebert has made the excellent point that del Toro transitions between these two dimensions of reality in Pan’s Labyrinth with a “moving foreground wipe,” namely, “an area of darkness, or a wall or a tree that wipes out the military and wipes in the labyrinth, or vice versa. This technique insists that his two worlds are not intercut, but live in edges of the same frame.” Swapped back and forth between the two realms is the vexing issue of unquestioning obedience to untrustworthy authority figures: the Captain shoots the village doctor for euthanizing a tortured rebel against his orders; the Faun, an obsequious, morally ambiguous trickster, bars Ofelia’s return to the underworld when she refuses his command to give him her baby brother as the blood sacrifice of the final task. Just as the Captain’s soldiers riding horseback up the hill start to look more like centaurs than men, the Captain’s dinner table, where he entertains corrupt local functionaries, echoes the ghastly dining table in the underground lair of the Pale Man.

An archetypal negative father figure and the Captain’s underworld coequal, the Pale Man is the Saturnian alchemical king who devours his sons in the process of mortification (melting or killing) of metals; del Toro references the Goya painting of this god swallowing his son as his inspiration. When Ofelia breaks a taboo and eats grapes from the Pale Man’s table, she brings the hibernating cannibal back to life. Popping his disarticulated eyes into slits in the palms of his hands (further elaborating this film’s eye motif, to grotesque and sinister effect), he staggers after her, devouring one of the unfortunate stick-bug fairies on the way. This violent act sends an alchemical ripple back into the upper world, where his alter ego, the Captain, in effect murders his wife by ordering the paramedic to save the baby over the mother, then murders Ofelia, whose death in turn becomes the paradoxically “blessed” act that fulfills her third task (shedding the blood of an innocent) and frees her to return to the land of immortals.

Pan’s Labyrinth ends much like Ingmar Bergman’s medieval-folktale-inspired The Virgin Spring, including a similar hint of local legend: just as a spring erupts on the spot where Bergman’s maiden was raped and murdered, the dead fig tree in the forest sprouts an incongruous flower after Ofelia’s death. The striking difference between the stories is that the double worlds of Pan’s Labyrinth are presexual. Though the figures of Ofelia and the Faun trigger echoes of Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast, the Faun does not woo Ofelia. In del Toro’s vision, this lascivious mythological figure has no genitals; neither does the Pale Man, nor do the fairies. Even though the Captain is almost exaggeratedly “Vidal”—full of life, sexual energy, violence—he sleeps downstairs, apart from his pregnant wife, to protect his unborn heir. When Ofelia crawls out of the ground under the fig tree after retrieving the golden key, her immaculate Alice in Wonderland dress and pinafore are smeared with dark mud, and she’s as distraught as if she had been raped. In the alchemical container of del Toro’s story, however, she’s gone through a chthonic initiation in the underworld that does not include sex—though, recalling the toad’s regurgitation, it’s worth noting that in the Middle Ages one emblem for a woman’s vagina was a toad skin turned inside out.

So far, this absence of eros is faithful to the tradition of children’s stories—and their deep roots in medieval folklore and romance—even as it avoids the racy Gothick eroticism we moderns are accustomed to. Where del Toro departs even from fairy-tale convention, however, is in denying his princess a mate. Pan’s Labyrinth ends regressively as Ofelia/Moanna’s prince turns out to be her baby brother, just as the servant Mercedes’s beloved partisan is no lover but also her own brother. Instead of marrying a prince in the underworld, Ofelia is reunited with a fairy-tale “father” (a wise old king with a white beard) and her aboveground mother, both now revealed as the rulers of the underworld, and ultimately makes her baby brother a prince—a chaste family constellation echoed in Hellboy II by the characters of Nuala and Nuada, the good sister/evil brother twin fairies who rule the autumnal underworld of this film when their father dies.

After her stepfather shoots her in the maze, Ofelia reappears in the underworld, inside a faux old-Gothic cathedral decorated with Celtic symbols (the screenplay says “vast hall,” but the vaulted interior boasts a spectacular rose window). Here her transformed mother and father sit on impossibly high golden thrones perched on spindly, Gaudí-esque columns. To complete this heretical Sagrada Familia, a third empty throne between the royal pair awaits the newly restored Princess Moanna. In this ritual reunion, as distant emotionally as it is physically, the princess’s parents are way too far above her for a hug—but of course none of these three immortals is human anymore.

We return to the dying Ofelia as we saw her at the beginning. The extended flashback that lasted the entire movie has taken up only a second in the “real” time line of this story—a neat demonstration of the collapse of space and time in the supernatural reality that del Toro has situated below, not above, the material world—and now the blood is running its natural course from her nose. At the moment of her death the camera closes once again on her staring eye, signaling either the end of Ofelia’s fantasy (if you’re a secular humanist) or (if you’re something else) the ancient Egyptian belief that the eye is the portal through which a dead person’s soul escapes into the afterlife. The Faun tells us that the princess ruled wisely in her realm for many years. And some of her goodness, he says as the discreet white flower blossoms on the dead fig tree in the forest, even had a small manifestation in the world above.

It’s tempting to insist, because it’s so psychologically authentic, that the true frame of this story is that of a suffering girl in flight from unbearable reality who is desperately imagining a happy ending in the last seconds of her life. Tellingly, when Terry Gross interviewed del Toro on National Public Radio, she described Ofelia’s “fantasy life” in just these terms, passing over the director’s rather astounding statement that although the story is set up to allow either of these two positions, he believes the reverse: that the other world Ofelia sees is “a fully blown reality—spiritual reality.” Gross for her part was expressing the psychologically oriented assumptions of most older mainstream viewers in the West—namely, the materialist side of the “Is this real or am I crazy?” conundrum so ubiquitous in genre horror film. In this equation, when something uncanny happens, the main character experiences it as a supernatural occurrence, but everyone else thinks that person is crazy for believing so. Though the original model for this archetypal setup, Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw, actually left the question open, the typical late-twentieth-century popular horror film went on to provide many independent proofs vindicating the main character: the supernatural is real, and he/she is not crazy.

Up until very recently this outcome has been considered acceptable only in popular entertainments, not in “serious” art, a fact that may offer one reason, finally, for Pan’s Labyrinth’s favorable reception with older art-house film audiences as well as horror and fantasy fans. Because this film allowed The Turn of the Screw’s double possibility—the underworld is real, or Ofelia is crazy—it could safely be labeled a political parable rather than that far more troubling animal, a story that positions the supernatural as a more powerful dimension of reality than ours in a hierarchical universe. Meanwhile younger audiences, more comfortable (in movie theaters, anyway) about accepting the supernatural as objective reality than as subjective delusion, were more likely to share del Toro’s perception—that on her throne in the alternate-world cathedral, Ofelia has become an immortal entity in a realm apart from ours.

There’s a contradiction here. Old-Gothic cathedrals are the diametrical opposite of scary Gothick haunted houses. They are places of light, not darkness, haunted by holy forces, not evil ghosts. A Gothic cathedral takes us from the shrouded porch of everyday life to the “unveiling of absolute light” (in Georges Duby’s phrase) in the magnificently vaulted nave. Part of a wider trend toward a new “bright” twenty-first-century Gothick, Pan’s Labyrinth retrieves the full spiritual universe of the old-Gothic Middle Ages, balancing the forces of light and darkness and accessed via the monstrous as well as the angelic. In its underworld cathedral, del Toro, like the twelfth-century Albigensians of Toulouse, has fashioned an entire parallel divine hierarchy, and one in which the feminine principle is given power.

Which brings us back to Cathedral Head. The idea behind it, the director has said, was of “somebody that, instead of talking about his home city, carried it around.” I don’t know how closely this creature’s forehead resembles Guadalajara Cathedral, but it’s fair to say the edifice del Toro carries around in his own head has been permanently molded, baby-in-a-jar style, by the Catholic church—and inside its sacred space I like to imagine there is a tiny chapel dedicated to Wilgefortis, patron saint of monsters. Where his hero, the twentieth-century master Luis Buñuel, could proudly proclaim, “I remain an atheist and a Catholic, thank God!” Guillermo del Toro can say, “I am a heretic and a Catholic, thank God!” And mean it.