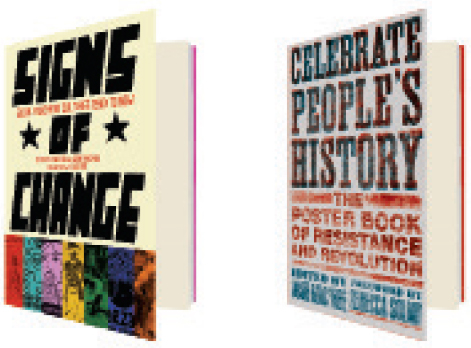

If you happen to be either a teacher in a progressive school or a politically minded college student, you may have spotted the posters in Celebrate People’s History: The Poster Book of Resistance and Revolution pasted to classroom or dorm-room walls. If not, now’s your chance to see the history of social justice interpreted by some of today’s most talented visual artists. To see rarely-glimpsed historical images and ephemera created by social justice activists across the world, look no further than Signs of Change: Social Movement Cultures 1960s to Now, Josh MacPhee and Dara Greenwald’s gorgeously designed catalog for the recent Exit Art exhibit of the same name. Taken together, these two books represent a departure from history as most of us learn it, both in form and content: Celebrate People’s History is a radical retelling of history by contemporary artists; Signs of Change is a visual record of historical events themselves.

Each full-page image in Celebrate People’s History comes from the full-size series curated by Josh MacPhee and celebrates “successful moments in the history of social justice struggles,” many of which fall outside the familiar canon. But these images aren’t what you’d expect—they’re not the old clenched fist pumping the air. “Rooted in [the] do-it-yourself tradition of mass-produced and distributed political propaganda,” the posters are stylistically diverse, each designed by an artist, including the likes of Jeff Stark, Swoon, Cristy C. Road, and Carrie Moyer. In the May Day poster designed by Eric Drooker, a celebratory army of figures with glowing red hearts and instruments clutched ecstatically in their hands rushes toward the viewer against a fish-eye backdrop of skyscrapers. The poster commemorates “the May 1st, 1886 nationwide protest for the eight-hour day and the following ‘Haymarket Affair,’ a pivotal event in the history of workers’ and anarchist movements in which four labor organizers were hanged by the State in Chicago.” Never celebrated May Day? Maybe that’s because it’s “a time of celebration and opposition throughout the world, except in the United States where it began.” These images are as much educational tools as they are aesthetic delights.

The posters offer graphic representations of everything from the Diggers to the Haitian Revolution, Eugene V. Debs to Wangari Maathai, Las Mujeres Libres to the Korean Peasants League. Many of these subjects have been overlooked, or actively erased, by mainstream history books. Take...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in