Maya Bookbinder and I are going to the Annual Taxidermy Convention, Competition, and Trade Show, a recurring shindig hosted most years by a red state and held this year in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, and to which folks drive in from miles, their rugged vehicles lugging trailer hitches stuffed with truncated deer heads mounted onto plaques of gleaming wood or badgers posed lifelike by pools of polyester resin or wildcats and mountain goats arranged mid-clamber up a fake boulder. Winners take home ribbons for the Champion Life-Size Mammal, the Noonkester Boar Award for best taxidermied boar, and the coveted Judge’s Best of Show. They hone their techniques at seminars such as “Fleshing and Tanning” and “Interactive Turkey” and shop for pelts, glass eyes, Critter Clay, and ear liners. They can sign up for a big game hunt in Africa or arrange to have their domestic pets freeze-dried for eternity.

Maya, a twenty-one-year-old art student at the Rhode Island School of Design, is firmly into “alternative taxidermy”—a blue-state hybrid born of art schools. When a professional taxidermist gifted Maya an imperfect coyote carcass, she skinned it and chopped the hide at the neck. Preferring the free-floating look, Maya didn’t attach the mounted head (in taxidermy-speak, to mount is to affix an animal hide to a premade animal-shaped form) to a plaque, as is typically done. A friend of hers really liked the result, so Maya gave it away. She last spotted “Scampers” leashed and attached to a wheeled board, being tugged around an art party in DUMBO by a stranger.

If realness is the aim of the average taxidermist attending the Annual Taxidermy Convention Competition and Trade Show, whimsy is the goal of the alternative adherents. But while their goals may differ—even contradict—the necessary skill set is the same. Most traditional taxidermists are mentored or self-taught, or are graduates of more official institutions such as the Second Nature School of Taxidermy in Bonner, Montana. Maya spent a few weeks living with Jan Van Hoesen, a Michigan-based, award-winning traditional taxidermist. Together they ate bear, cared for Jan’s pet bobcats, hit the regional taxidermy gathering, and worked on some animals. Jan was horrified to learn that Maya intended to use her newly sharpened skills to create weird-ass, fantastically reanimated animals. Traditional taxidermists have no truck with urban art schoolers fashioning coyote pull-toys from God’s majesty.

If realness is the aim of the average taxidermist attending the Annual Taxidermy Convention Competition and Trade Show, whimsy is the goal of the alternative adherents. But while their goals may differ—even contradict—the necessary skill set is the same. Most traditional taxidermists are mentored or self-taught, or are graduates of more official institutions such as the Second Nature School of Taxidermy in Bonner, Montana. Maya spent a few weeks living with Jan Van Hoesen, a Michigan-based, award-winning traditional taxidermist. Together they ate bear, cared for Jan’s pet bobcats, hit the regional taxidermy gathering, and worked on some animals. Jan was horrified to learn that Maya intended to use her newly sharpened skills to create weird-ass, fantastically reanimated animals. Traditional taxidermists have no truck with urban art schoolers fashioning coyote pull-toys from God’s majesty.

*

The week before we depart for the National Conference Maya brings me to meet Tia Resleure. Tia lives in a tucked-away Victorian in San Francisco, her street more a quaint alleyway. A slender white statue of a greyhound marks her staircase, and as I peek through the glass on her front door I spy a taxidermied rabbit standing on its hind legs, a hobo bag knotted on a stick slung over its shoulder. A taxidermist in her own right, Tia also owns an impressive collection of antique specimens, most hailing from Victorian England, where every village had its own taxidermist and it was common practice to preserve your pet. Beside the hobo rabbit stands a frightening morph of cat and bunny with a stunted tail and ferocious little teeth that looks very, very old.

Tia is intense and protective; having been the object of animal rights protests, ill will, and general misunderstanding, she is cautious. “I just got an email calling me a sick cunt,” she says shortly after I enter her house. Everywhere I look, there is taxidermy. A duck, its green head iridescent, balanced on a sparkling purple circus ball—Tia’s own creation. Taxidermied lapdogs pose in glass cases or beneath Victorian glass domes; some are freestanding, pastel bows ringing their necks. A cyclops fetal pig bobs in a jar of formaldehyde, which Tia says she received “from a really awful guy I dated.”

Tia is in her forties, with a strong-featured face, penetrating blue eyes, dark hair blasted with gray above her forehead and gathered in a scraggly ponytail. Her arms are wildly colored with tattoos and she discusses with beguiling openness her many strong opinions and shocking upsets. Like Maya, Tia had to delve into the world of traditional taxidermy in order to acquire the skills to work on her own vision, which includes, among other things, taxidermied winged cats. She enrolled in the John Rinehart Taxidermy School in Wisconsin. “When I was taking that taxidermy class I was so intimidated, because all the other students were bubbas that have been hunting their whole life,” she recollects.

We gather around a wooden dining table cluttered with half-completed projects. Through the smoke from Tia and Maya’s cigarettes I spy a fetal dog on a dinner plate. The dog’s head has come off; its interior stuffing of dry sticks looks like tobacco.

“Oh my god, the dog fell apart,” Maya says. I notice lots and lots of stillborn puppies around the room; a Victorian specialty called Roman Dogs, they look incredibly, magically miniature, especially all piled together, beribboned and frolicking beneath a glass dome.

“This stuff is called tow,” Tia says about the stuffing. “It’s like a plant fiber. The rest is plaster. That’s probably why it broke.” She guesses the dog dates back to sometime in the 1860s. “This is a wire from the tail,” she says, holding up a thin strip of rust. “I’ll try to repair it, and if not I’ll put a different puppy in here.” The mangled puppy’s diorama is a bleak, urban backyard; placing animals in scenes both fantastical and starkly realistic was common practice in the nineteenth century. “Obviously a theme was going on with brick courtyards and dogs,” Tia comments. “The industrial age. All these dogs are out in crappy doghouses.”

Behind the work-in-progress is another Roman Dog, this one eight-legged. Behind it is a stuffed duiker (a small variety of antelope). A deer is arranged on a velvet divan beside a slender Italian greyhound. The greyhound moves. The greyhound is alive. Tia, I learn, has worked as a veterinarian’s assistant and runs an Italian greyhound rescue. Her three pet Italian greyhounds are show dogs; they constantly strike dog-show poses around the house, further blurring the already fuzzy distinction between looks-alive and is-alive. The mounted head of Tia’s first pet greyhound hangs on the living room wall. “One of the things I think is so interesting about taxidermied pets is, it’s very controversial,” Tia says. Though the practice was so popular in Victorian times, many of today’s taxidermists either refuse to work on pets or charge an exorbitant amount. “They say the reason for it is people freak out when they see their animals, and they don’t get paid,” Tia says, and laughs cynically. “I think the reason they don’t do them is they don’t have the skill. They don’t make forms for domestic pets.”

These days taxidermy involves, essentially, the stretching of a fur coat over a foam mannequin called a form. You can buy forms of all commonly taxidermied animals, but if you are working outside the mainstream like Tia, you’ve got to make one yourself via a process called carcass casting. Using the skinned carcass of the dead animal, you make an intricate series of plaster molds. Segment by segment you work with the carcass, isolating the targeted area by submerging the rest of the body in sand. The molds are then tied together and filled with an expanding foam that hardens into a form for the pelt to be stretched over. It’s a lot of work.

“She’s the first dog I ever mounted,” Tia says about the slender, slightly distorted face jutting out from the wall. “Her euthanasia went bad, I couldn’t deal with it, so I kept her in the freezer for a few months.” When she eventually pulled the dog from the freezer, she was hit by a bolt of sadness that swiftly evaporated. “All the emotional stuff went away,” she says, “and it became pure science.” A live greyhound skitters nervously over to Tia and strikes a needy pose. “Oh, Simi, you’ll be up here, too,” she coos, “and we’ll adore you just as much.” Below the greyhound mount is a gigantic diorama featuring a monkey poised to shave a kitten with a straight razor. Strange dolls stand on painted cliffs behind them.

“It came from Bristol,” Tia explains, “and Bristol had an Arab slave port. So you got your Arab on the right and your two Africans on your left, and it was probably a display for a barbershop. It’s in the process of being restored.” Most of Tia’s vast collection was inherited from an uncle. It is extremely difficult to acquire such pieces otherwise. Animal protection laws make no exception for antique taxidermy, and pieces that were made long before any of the animals were protected are often confiscated and destroyed. Natural history museums, some of the only institutions licensed to own such works, don’t want pieces that are fanciful or ecologically incorrect, such as a flamboyant tree hung with species of songbirds that would never naturally share the same branch. So it is destroyed. There is no real movement to preserve these pieces as works of art. “I keep thinking that someday I’ll have official museum status,” she dreams. “Nobody is looking at taxidermy from a Victorian cultural perspective and valuing it for that.”

I wheel about Tia’s home, taking in a taxidermied wallaby, the shriveled head of its baby poking from its marsupial pouch. A terrier, its long hair sweeping the floor, encased in glass. Squirrels playing poker. A dome curves over a fluffy, fantastical array of stillborn kittens, incredibly small. “It’s easiest to do moderate-sized animals,” Tia says. “Working on little puppies and kittens—their skin is very delicate. Almost all kittens are like working with wet toilet paper. And rabbit fur falls out easily.” I ask Tia how traditional taxidermists view the old ways of stuffing animals, rather than stretching their hides over a form. “Oh my god, they so sneer down their noses!” she cries. “To them, stuffing equals the really shabby, really crappy, bad technique, and I’ve seen lots of beautiful things that have been stuffed.”

Tia owns a few pieces from renowned Victorian taxidermist Walter Potter, whose extravagant tableaux, often inspired by nursery rhymes, are the definition of playful taxidermy. Tia’s website, A Case of Curiosities, features a chronology of the artist’s life. His collected works, kept together for decades after his death in 1918, were broken up and sold at auction in 2003, an action viewed by Tia as scandalous. Her own Potter works include a diorama of rats escaping with stolen eggs, and a single, startling rat whose teeth, improperly maintained while alive, had grown into curving tusks.

“I’m looking for a charming deformity,” she says brightly, directing my attention to a spooky white creature. “That’s an albino mole. When I first started getting into the freaks I was really into albinos. Now that I’m running out of space the albinos seem kind of passé to me. But I’ve always been fascinated with the freaks.”

Tia’s childhood functions as a background swirl of impulse and inspiration, fantasy and horror, that feeds her current obsessions. “My interest in taxidermy kind of goes all the way back to being a kid and having parents that collected stuff. And the stories I would hear about my father before he killed himself—he made a headdress out of a whole zebra head. He was really queer in the ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s. He glued sequins to his Pekinese and had her sit next to him while he played piano so she’d sparkle.

“As a child I was disconnected from reality because my life was really crappy and violent,” Tia continues. “The family dogs were the only people that would talk to me. Everyone in my family has very intensive relationships with animals, but in very different ways. My one sister’s got a hole in her screen window so she can shoot the rats in the garbage. My other sister was trancing out in the winter and saying she had to rescue the worms on the street. There was a fly that she fished out of the pool and massaged its abdomen and brought back to life. There’s all this animal stuff. I worked for my vet. I loved doing surgeries. I’m fascinated by that.” Her narrative winds back to her family, an uncle that killed her grandmother with a hatchet in a hotel in Lafayette, California. “I got the honors for cleaning up the mess. Back then they didn’t have services.”

“For me taxidermy is playful,” she continues. “It’s being able to escape into another world. When I’m working I’m making up stories about them. I spent a lot of time as a kid hiding in my closet. I was reading the Lord of the Rings Hobbit book over and over and over again because I just wanted to be there. My mother gave me a whole batch of pot brownies. What kind of lousy mother would do that?”

Tia gets up from her chair and fishes a piece of plaster out from a jumble of taxidermy. “I’m the most normal one in my family,” she states, and shows me her treasure. “I did a death mask of my mother. This is Death Mask of a Martyr.”

Tia has a lot to say on the subject of animal protection laws. She differentiates between animal rights (no) and animal welfare (yes). “The hardcore animal rights activists don’t want us to have anything to do with animals, which includes keeping sheep for wool or bees for honey,” Tia says. Although Tia doesn’t hunt, and all of her animals died naturally or were necessarily euthanized, many animal rights activists find the spectacle of taxidermy inherently upsetting and offensive. “They were giving me shit and saying I was insensitive to animals and was going to hell because I did some fetal kittens. They thought it was disgusting, that I was objectifying them.” Other visitors to her home-based Italian greyhound rescue were shocked to find the breed among her stuffed menagerie. “I had a lady come over and say, ‘I thought you were a dog lover!’ And I said, I just love dogs more deeply than anyone you know.”

*

Maya Bookbinder phones me the night before we leave for Sioux Falls, to inquire how my packing is going. Maya instructs me to pack conservative outfits. It will be in our best interest to pass not only as heterosexual, but as culturally “normal.” Maya has a cute flop of hair on her head, a latter-day mullet. Twin silvery rings loop through her nose and she sports a schlumpy-cool layered look. Like me, Maya looks queer and artsy. I hang up from our conversation with despair in my heart. People don’t understand how hard it is for me to look normal. Or how traumatizing it is to even have to try. Every job interview, every meeting with a prospective landlord, is preceded by hours of freaking out before my sizable and wholly inappropriate wardrobe. Most every outfit makes me look like a child, a whore, or both.

I pull an American Eagle Outfitter corduroy skirt from my closet. I bought it at a church garage sale for exactly these sorts of demoralizing occasions. But what about the tattoos that stretch all the way down to my knuckles? I have a pair of cowboy boots, but they say fuck on one foot and yeah on the other. I try to scrub off the fuck with a slab of Scotch Brite but it doesn’t come off, and now the letters look brighter contrasted against the wet leather. I grab a pair of jeans and a blousy ladies’ shirt, sort of ’80s secretary, and a braided silver belt. Is it too flashy? I am going to look like Nick Rhodes. It is very New Romantic. With the cowboy boots? I’ll look like a fag. Can a girl get fagbashed? If anywhere, perhaps at a taxidermy conference. The temperature in Sioux Falls is approximately ninety degrees. I pack my bathing suit, and for a cover-up I choose an enormous T-shirt with a deer head silkscreened across it. If all else fails, I will just wear this shirt. Again I feel a wash of panic at my inability to gauge the situation. I will be in a hotel stuffed with dead animals and the Christian men who shot them. If I want to pass as normal I should probably be packing a gingham dress and a dainty gold cross to wear around my neck. Perhaps, I think, I am experiencing a certain gender dysphoria. Perhaps part of the problem isn’t just not understanding “normal,” but not understanding female. Which really isn’t normal if you’re a female, which I am. I zip up my duffel bag which, thankfully, has flowers all over it.

*

All afternoon, as my flight to South Dakota gets increasingly delayed due to the intense summer heat melting the tarmac at Denver International, I field phone calls from Maya. Already at our hotel, she excitedly details the multiple swimming pools, the miniature water park, the fish mounting seminar that’s already in session, the free back-issues she scored of the NTA’s official publication, Outlook. I finally touch down in Sioux Falls well past 10 p.m., and share a cab to the hotel with a lanky white guy dressed in shorts and sandals, shaggy light brown hair poking out from a baseball hat. His wire-rimmed glasses flash on his face, and in the dim light of the taxi I make out a shine of adult braces on his teeth. “You don’t happen to be on your way to a convention, are you?” he says hesitantly. Why yes, I am! “A taxidermy convention?” he asks skeptically. That’s right. He is visibly shocked. “Are you a taxidermist?” he asks. I tell him I’m a reporter from San Francisco and life makes sense again.

My copassenger’s name is Stefan Savides and he has been a taxidermist for forty years. “I’m at the top of my career,” he boasts. Stefan lives in Oregon and is such an accomplished waterfowl taxidermist he is now routinely flown to competitions to judge them. That’s what he’ll be doing this weekend, inspecting the waterfowl for signs of shrinkage in the webbed feet, for symmetry in the placement of the feathers, for care taken to artful display. Stefan dabbles in other arts, and looks forward to moving out of taxidermy and into bronze sculpture.

Inside the hotel I depart from Stefan and wind toward my room. I pass through a hallway boasting a banquet table all set up for morning—rows of white coffee cups surround a centerpiece composed of a deer head, a sheaf of wheat wrapped in a red bandanna, and a couple of toy pistols. Around the corner are tables featuring items for the silent auction. A life-sized doll appears, at first shocking glance, to be a taxidermied eight-year-old in a Renaissance fair costume.

In our room Maya and I buzz through the list of seminars offered at the conference. Maya is on the hunt for specific skills and, really, I’m looking for the freaky stuff. There’s Crappie Mount, and Money-Making Whitetail sounds sort of hot, but we settle on the 8:30 a.m. Fleshing and Tanning seminar, perhaps followed by the Be a Pampered Chef “Ladies Seminar” later that afternoon.

Women, we will soon learn firsthand, are a cutesy minority in the taxidermy world. To its small credit, Outlook has a regular female columnist, Cindy Crain, whose photo shows a full-cheeked woman with a showgirl’s headdress of blond hair and a bunch of gold jewelry. Her columns are perky and religious: multiple relatives’ triumphs over cancer, possible cosmetic uses for taxidermy pastes, and a Christian treatise on adjectives that ends: “The words awesome, incredible, wonderful, miraculous and extraordinary are words that belong to Him.” I settle into my wide hotel bed. As we drift off, Maya tells me about a conversation she had with a friend of hers, a genderqueer person who doesn’t “pass”—who doesn’t look physically female enough to be perceived as such by the world at large.

“She’s doesn’t pass, and she likes it that way,” Maya says of her friend. “We were talking about queering taxidermy. Taxidermy is all about passing, passing as alive. It’s actually really gay.” Using ideas from queer theory, we talk about a radical, antiassimilationist school of taxidermy, taxidermy that, like Maya’s friend, uses the power of not passing to call ideas about realness into question. A punk taxidermy. “When the eyes don’t align,” Maya says dreamily. “Shit coming out of the nose, things peeling…” Tia’s Charming Deformity. We fall asleep.

*

In the morning we try to pass. Slurping a cup of brewed-in-the-room coffee, the curtains pulled against the nuclear glare of the South Dakotan sunshine, I twist my hair into three different hairdos before hitting on one that Maya affirms is subdued. I pull on my many layers, stretching the sleeves of my cardigan over my fingers. I am inoffensively earth-toned and makeupless. My cat-eye glasses may be unusual, but I couldn’t look any blander. Maya is wearing a pair of shorts and a couple of tank tops; she pretty much looks like Maya without a spiked belt. She seems unconcerned about her own tattoo, a work-in-progress of various laceworks inked in black on her forearm. I clutch my weak-ass cup of coffee and we walk out into the conference.

The taxidermy festivities dominate the entirety of the Best Western. We pass a booth selling T-shirts emblazoned with the silkscreen of a giant crucified hand, a bolt driven through the palm. Body Piercing Saved My Life reads the text above. A trail of kids are lined up outside the “Kid’s Seminar,” which I really wish we could attend, since the offerings are guaranteed to be at my skill level, but the only thing worse than suspicious outsiders are suspicious outsiders lurking around children. We grab some fruit and bagels from a banquet table and find the room hosting the Fleshing and Tanning seminar. Garish flourescent-lit panels are set flush into the ceiling. Bad casino carpeting twirls over the floor, and regulation hotel artwork—dappled streams, wild mustangs—hangs on the walls. Only a couple of men are settled into the aluminum folding chairs. At the front of the room are twin industrial machines, iron drums rigged rotisserie-style, affixed with wires and gauges. “It could be a type of tanning machine,” Maya guesses. She is unimpressed. “I just get a bucket and fill it up with acid.”

The instructors enter the room. Gerard Tessier is a sixtysomething Quebecois with a knee brace who is here to promote his fleshing machines. He wheels a sample into the room—a tall table of raw lumber with a motorized blade affixed to one side. There’s a hole in the table and a trash bag tacked there, to catch scraps. Gerard surveys the room, ignores me and Maya. “We got two brave guys!” he says, congratulating the men in the room—one dude with a badly sunburned head glowing purple through his military buzz cut, and another who looks like an aged and muscular Steve from 90210. Maya gawks at me with her mouth hung open. We cannot believe we have been dissed so soon, so early in the morning.

The second instructor, Dan Rinehart, seems embarrassed. He walks over and personally shakes our female hands. Dan is younger, late thirties. Like pretty much everyone here he is white and regular-looking. He’s wearing a polo-style shirt with a Calvin Klein logo and is the son of John Rinehart, as in the John Rinehart Taxidermy School John Rinehart. Dan was an instructor back when Tia attended his father’s school (Dan’s now the owner), and of course remembers her because the woman is unforgettable. “She was mounting chickens and putting them on disco balls!” he recalls. He’s shocked to hear that she’s in business, even more shocked to learn she’s currently working on Italian greyhounds. “Is there… a client base for that?” he asks. Maya nods, nonchalant. “Collectors,” she says. “She sells a lot.”

Dan is here to push the pressure tanners, those mechanical iron cauldrons. “Today I’m going to go over the physics of how the pressure tanner works,” he promises, and does he ever. He passes out a five-page, illustrated handout that explains the physical process of tanning in minute, excruciating detail. The coffee I am drinking and cursing turns out to be decaf; I am utterly lost. Dan is plugging a financing deal for his tanner, a mere $139 a month, $84 for the smaller model. The Fleshing and Tanning seminar is actually just an infomercial for expensive equipment.

Dan asks if anyone has used a pressure tanner before and sure enough, 90210 Steve has. But he doesn’t like the machines. The enamel comes off, they turned his hides purple, and they’re not big enough to do buffalo.

“A machine is only as good as its operator,” Gerard says. I wait for Steve to react but he just stares down at the psychedelic carpet.

“Kentucky Fried Chicken has their own pressurized cooking system,” Dan says. “This is similar.”

“The women are very used to, in the kitchen, a pressure cooker,” Gerard says with a nod to me and Maya. I set my useless coffee down with a hostile rattle.

Dan directs our attention to an older man who has walked into the room, ruggedly debonair with the look of a star of films, possibly Westerns—silver, styled hair, sharp blue eyes, and boat shoes. His name is Bruce. “We have a tanning expert in the room,” Dan says, excited.

“I’m a learning expert, Dan,” is Bruce’s humble reply. His voice is gravelly and low; you can barely hear him. He nods his head. “The pressure tanning system is a good system.” “I love that guy,” Maya whispers. His charisma livens the dull morning room. So does Dan’s next move. He cracks open a dirty cooler that’s been sitting on a table and removes a small plastic bag stuffed with something heavy and wet. Using a pair of scissors he snips open the sack and pulls out what looks like a long, wet donkey mask, its ears big and floppy. It’s a very fresh deer hide is what it is, and as Dan smoothes it out, flesh-side up, I realize I’m not breathing. I don’t want to smell the hide. Something that slick and raw has got to have a smell. It might not even be a bad smell, it may simply be a smell I haven’t smelled yet, but I am resistant. I take a hesitant sniff of the air. Nothing but Gerard’s pipe and my Judas coffee.

Dan is fleshing the hide the old-fashioned way, with a curved, dull-looking knife. “No gloves,” Maya notes, her face scrunched in the universal expression of Gross. Dan’s bare hand grips the pelt—called a “cape” in taxidermy lingo. He runs the fleshing knife over the reddish stretch of deer, methodical, each brush bringing up a ridge of fat and meat. When the ridge gets too tall he dumps it onto the bare table, a little whitish pink pile. He lifts what appears to be an ear and turns it inside out like a soggy sock. With a smaller tool he begins to whittle the flesh away. Aside from my fear of the smell, I’m surprisingly not grossed out. The most brutal part would have been the killing of the animal, and, as it is with the meat I eat, I am spared from that. Dan’s bare-handed handling of the fleshy cape reminds me of nothing so much as my mother making meat loaf, plunging her own raw hands into a bowl of ground beef, mixing a slick run of egg into the mess, making dinner.

“He’s doing cool stuff over there you can’t do with a machine,” says Maya, a sort of taxidermy Luddite. “The nose and eyes and ears.” Dan reaches the part of the ear that is tight with cartilage. He flips it back and inserts a long metal tool. You can hear the slight tear of the cartilage. The room has begun to fill up some. An older Southern man with a name tag that says Melvin rises from his seat in the front row and offers to help Dan. Dan gives Melvin the other ear, and he eagerly slides the tool inside it. This is called “turning the ears.”

Meanwhile, Gerard brags about his fleshing machine. “I predict that this machine will be the machine of the future. I have made miracles, I think.” He brandishes a cape that is ready for the machine. It is dry and looks way less recently dead than the cape Dan and Melvin continue to pick clean. This one is long-haired, a Canadian deer. As Gerard plops it onto the fleshing machine I can see the head, collapsed in soft folds. The nose is dark. He brings the blade to life with the flick of a switch and brings the hide of his pelt, lumped with yellow chunks of dried fat, to the spinning edge. He stretches the pelt back and forth over the blade, shaving off thick ribbons of rubbery skin, which he knocks down the hole into the trash bag. The motion of his hands and the whir of the blade produce a slight wind, which wafts a new odor my way. It’s the smell of the pelt, a faint smell, not terrible but I’m still phobic of it entering my body. Then Gerard lifts the shorn hide and brings it over to us, the girls, for a look. I decide to breathe. The smell is unfamiliar but not rancid. Scraps of yellowy corium, the outermost layer of pelt, dangle like jerky around a perfectly smooth, finished hide. “Nice,” I say.

The seminar divides between dudes who gather around the fleshing machine to give it a try, and Maya and I, who get up close to Dan. “What are you doing?” I ask him. “Just getting the membrane off,” he says. “This is a whitetail deer.” The inside of its ears, now fleshed, are a deep purple-blue. I ask Dan, whose girlfriend is a vegetarian, about the taxidermist’s life. “If a hunter doesn’t get taxidermy done, this is wasted,” he nods at the cape he’s

just prepared. “This way, the beauty is preserved. It’s not us that’s taking wildlife; we’re preserving it. Our artistry is not understood. You have to attend the shows to see it.”

*

The taxidermy that has been submitted for prizes is arranged in a great hall behind the hotel, but no one is allowed in to view it until the judges have made their decisions. Maya and I trot across the street, which sends up wavy shimmers in the heat, so

I can grab a Red Bull from the gas station. Back outside the hotel we sit on a bench in the shade so Maya can smoke. She tells me about her job working at Evolution in New York City. “It’s a natural history store for celebrities,” she says of the place which sells, among other things, tanned frog change purses, raccoon penis bones, and pinned insects. “Robin Williams came in a lot, Angelina Jolie, the guy who plays Mango on Saturday Night Live. The owner was in jail for a year for selling illegal Indian skulls. He sold elephant paw ashtrays that were illegal. And the Indian skulls—these different tribes made him send them back so they could bury them. The second I started working there I was like—I want that, I want that.”

Maya lives in a vegan household, with at least one roommate who is a passionate animal rights activist. Although she was vegan when she moved in, her resolve is slipping. “It was definitely easier to taxidermy vegan,” she admits. “I think identifying as a vegan taxidermist helped with my guilt. Plus, I got a lot more creative with cooking, and I found it much cheaper. And I felt a lot healthier.” I tell her about my own tango with veganism, when I was exactly her age and deeply stunned by the world’s rampant injustice. I tell her how I slowly cut away everything that I thought might assist the destruction of the world and its people. I was slowly starving to death, eating raw organic bell peppers. I was going to live in the woods and grow vegetables, only I didn’t know how to garden, didn’t really know where any woods were, and didn’t know what to do about the synthetic fibers in my sleeping bag. “I can’t care about things in moderation, like a normal person,” I told her. “So I have to not get too riled up about anything.” An attitude, I am sure, that helps me be relatively comfortable here at the taxidermy convention, which is filled with people who do things I’d rather they didn’t, like shoot elephants and vote Republican.

Back inside the air-conditioned hotel, we poke our heads into various empty seminar rooms. One holds a deer head, the hide freshly glued to the mount. Tubs of Critter Clay sit on a table, and the air holds that cold, wet smell—part chemical, part organic. “Critter Clay is so great,” Maya says. She brings my attention to the animal’s eyes. The eyes are perhaps the hardest part of taxidermy; it is difficult to realistically set the glass eyes, but the skinning process is even more arduous since the delicate skin of the eyelid is easily torn. A torn eyelid is skinned away entirely and a fake one sculpted with clay, to lesser effect. “You gotta keep the eyelids to make it look natural,” Maya says. She directs me toward the ears, which, unlike the floppy pockets I just saw Dan Rinehart scrape empty, are erect on the mount’s head. “When you skin the animal it’s all cartilage up in the ears, but you got to get rid of cartilage because it rots,” she explains. Plastic inserts called ear liners, which look like thin shoehorns, are slid into the ears to hold them upright. “You can feel the ear liner go all the way to the edge,” she says, inviting me to feel the furry tip. I notice a pin jammed in the deer’s head. “To pin it down and keep it in place,” she explains. “I think this was done like thirty minutes ago.” In fact, we are standing in the debris left behind by the Money-Making Whitetail seminar.

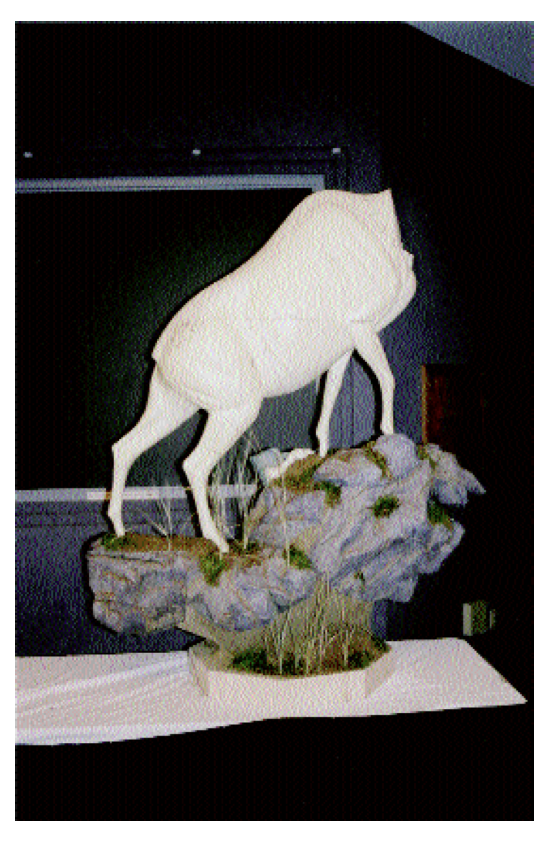

Outside in the lobby, a man named Dave Hale—scrappy in a biker sort of way, with dark hair and a mustache—is creating a majestic deer antler from scratch, using plaster and wire. Still an unfinished, chalky white, it’s rigged up on some poles, drying. Dave sits on the arm of a stuffed chair, watching it. “This way you can do anything you got for an idea,” he says of the do-it-yourself advantage. “You’re only limited by your imagination.” You’re also less limited by income, as a real whitetail antler can cost upwards of $15,000. He talks to me, as others will, about how hunters have done more than anyone to preserve wildlands in America. “A lot of the tree-huggers, all they have to do is start looking at statistics and see how much more we got. But that’s human nature,” he sighs. “Everyone can’t get along. Taxidermists used to be considered the right hands of kings. Now, it’s like you’re some redneck, drunk, living off the dirt of the land.”

I hear my named shouted behind me, and turn into the crowd that has gathered to listen to Dave. “You have friends here?” asks Maya, confused. I do. It’s Stefan Savides, waterfowl judge, and he has gotten us a special clearance: we can enter the competition room and look at the work, now, while the judges are determining their favorites.

*

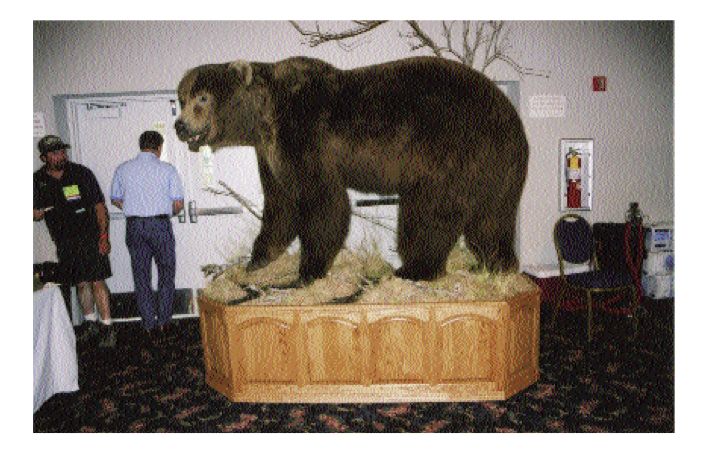

Everywhere I look there are animals—freestanding, mounted onto pedestals and decorative furniture. Smaller pieces are grouped on wide tables, larger pieces are mounted onto the walls. The room is softly carpeted and the lights are mild, not fluorescent. Everywhere is shining fur and shimmery feathers and those glassy, glassy stares.

Stefan likes to begin with evaluations of crappier pieces, steadily moving through the entries, saving the work he admires for last. He inspects a pair of subtly misshapen bluewing ducks mounted on stylized steel waves with the aid of a green plastic flashlight. With the assistance of Stefan’s expert eye I notice the asymmetry of the ducks’ backs, the shriveled cast to the dangling webbed feet. Then there is the problem of the base, a simple wooden table painted black and gobbed with shellac. A shelf at the bottom is piled with heavily glossed “rocks” that look like charcoal, or turds. “Looks like a horse came by,” Stefan remarks.

Stefan has handed me his judging paperwork and a pen and, under the guise of aiding me in my reporting, has employed me as his little assistant. “Mark that box,” he instructs quickly. “Mark that box there.” He hovers over the birds with his flashlight. He catches me taking notes. “Hey, you’re supposed to be making marks for me,” he scolds. I’m grateful for the backstage peek at the taxidermy but do not want to be Stefan Savides’s intern. I pass him back his paperwork and drift into the animal maze. A local television show is filming a spot for the evening news. The newscaster—a gray-haired man stuffed into an ill-fitting suit—is crouched beside a deer mount. Raccoons dangle from branches behind him. “These aren’t stuffed animals anymore,” he croons in a classic newscastery voice. “They’re works of art.” I walk over to Maya, who is gazing at a taxidermied bear cub slumped on a tree branch. “Did you see how they all have a wet nose?” she asks, pointing to the realistic moist sheen on the cub’s snout. “A lot of them have weird things in their mouths too, little leaves and stuff.”

Judges, clustered in groups or working solo, huddle intensely over various works. I breeze by Stefan, who has moved on to the next substandard effort, a humble black and white seabird on a rock. “The color of this bill is too dark,” he mumbles, and makes the corresponding mark on his paperwork. I see not a too-dark bill but a tactile lump of cuteness and sadness, inspiring within me the urge to pet and, foolishly—belatedly—protect. I feel somewhat ashamed of the reactions the taxidermied animals elicit from me. They aren’t so different from the feelings stirred by my living pet cat. I like to think I have some sort of relationship with the domestic shorthair I call Petunia, but if this dead bird, this statue, triggers the same emotions, what does that say about the integrity of our feline-human connection?

Stefan’s next piece is an extravagant diorama—three ducks splashing in a wide resin lake. Beneath the duck’s feet, suspended in the resin, is a full underwater scene, replete with fish swimming around and eating each other. Stefan is distraught. He has in fact scored this exact piece in a previous competition, and if he gives it a markedly different rating today it will make him look inconsistent, his opinions perhaps less valid. I leave Stefan to his struggles and move toward one of my favorite pieces, a pair of black squirrels with crazy tufted bat-ears. I have never seen such an animal before, not in a zoo or on an animal-centric cable station, which is where I experience animals. The squirrels are mounted upright in a pile of autumn leaves and I love them. Maya pulls me over to observe a fish mount. It is a brook trout, which is no big whoop except it is gripped in a fake human hand. A male hand wearing a watch at the wrist, sparse black arm hairs curling out from under the cuff of a flannel shirt. Throughout the course of the day the piece is surrounded by groups of admirers who gasp and murmur appreciatively. One such admirer is a blond woman named Kim Owens, who co-owns a taxidermy business with her husband in Lubbock, Texas. “I like it,” she nods. “It’s a beautiful paint job. Hands have been done for years, but this is the best one I’ve seen. Notice how the hand is wet up here,” she points, to a splatter of resin, “not up here?”

Kim, like most of the other taxidermy women I’ve observed, has a working-class hardness that feels familiar. She’s not so different from the women in my family who make their living doing the difficult work of caretaking the malfunctioning bodies of the elderly in nursing homes. Both are labor-intensive, both involve the gross realities of physical bodies. “Taxidermy’s a hard business,” Kim says. “So many people get into it because they like to hunt and fish, but it’s completely different from what you think. It’s extremely expensive, overhead-wise. Your labor. Rent and electricity. In this day and age, you can’t do a $225 deer head and make any money.

“What people don’t understand—the layperson or regular laborer who does his first deer hunt—is that taxidermy is expensive, and it’s a luxury. If you don’t have any milk or any bread, I don’t want you to bring something into my shop. Because you’ll never come back for it. We’re all constantly waiting for people to pick stuff up.” Kim attempts to minimize visits by these deadbeat hunters by keeping her prices high. “You’ll do more work for doctors, lawyers, and Indian chiefs,” she says.

*

It’s midafternoon and Maya and I drift over to the ladies’ seminar, “Be a Pampered Chef.” In the same room that once held Dan Rinehart, his bare-handed fleshing rendering drifts of fat and membrane, there is now a cooking class hosted by a super-bubbly young woman with a Kewpie doll face. And, much like the Fleshing and Tanning seminar earlier, this class is really a giant infomercial for the Pampered Chef line of cooking utensils. She pulls out a six-inch knife and quips, “This is also a home security device!” She personally greets Maya and me as we slide into our seats, but instead of making me feel included I feel instantly trapped. The woman is demonstrating a newfangled cheese grater. “Isn’t that grate?” she puns. “Get it? Grate! And on a bad PMS day you can throw some chocolate in it and…” she angles the device over her face and pantomimes grating a fall of chocolate into her open mouth. The talk of chocolate and cheese remind us that we are starving, and we decide to ruin Maya’s vegan intentions at the Mustang.

“All the children here look so Aryan,” Maya says with a shiver. “They’re so fucking blond. Did you notice the one person of color?” I had. In an earlier seminar a single teenage black boy sat, bored, in a sea of whites. We refuel with some nonvegan chicken quesadillas that are the best thing I’ve ever tasted. The key to eating good where the eating is bad is to starve yourself to the point that iceberg lettuce and sour cream taste exotic. Sated, we hightail it over to the trade show, as yet unexplored. I am drawn toward a wide area advertising a certain freeze-dry taxidermy business. A hand-lettered sign reading Follow your passions—I did hangs on the wall above small, freeze-dried animals—a mole, a squirrel. On the floor, curled in the corner beside where the proprietor sits on a stool, is a freeze-dried, rust-colored pit bull. A sign above it reads Beware: Let sleeping dogs lie. “He’s been to a lot of shows, dragged around and not taken care of,” the man apologizes for the specimen, which looks fine to me. It looks just like a snoozing pit bull, maybe a little long in the tooth but not too shabby. I ask him if he positioned the dog in that sleepy, fetal roll and he nods. “Once they’re frozen they’ll stay in that position,” he explains. “It’s slow, ’cause you’re working at a hundred degrees below zero. When it comes out there’s no moisture, so it can’t thaw. You can get really creative.” A second freeze-dry outfit is set up at the other end of the hall. Let us freeze dry your pets, a sign suggests. I watch a small boy, maybe six years old, approach a freeze-dried cat with a smile. “Awwww,” he smiles. He is one of the Aryan children Maya was speaking of, and truly they are everywhere, a legion of towheads. The boy reaches out and strokes the cat. He stops abruptly and moves away. “It’s dead,” he says. His voice is blank, not grossed out or scared or surprised, just informing himself of the state of the cat. He runs off to join a gang of children, blond.

Walking down the aisle, I come upon Maya before a booth lined with industrial glass bottles, like a strange apothecary. There are bottles of reptile stain, bottles of bird feet injection. Across the way is Dan Rinehart’s booth. Mannequins crawl across the booth’s back wall, looking alien and larval, sleek mammalian creatures with no skin, no ears, no definition. Gerard Tessier is there, demonstrating his fleshing machine. “He’s got some serious man-titties,” Maya nods at Gerard, reading my mind. In fact, when I first spotted Gerard, with his grown-out silver brush cut, lavender T-shirt, and lanky frame sporting undeniable man-breasts, I thought he was a butch lesbian, and a rather handsome one at that. My heart leapt. Then I realized it was Gerard. He notices our stares and looks away. “I think he thinks we’re creepy,” Maya whispers. “Oh, the irony,” I say, but it’s true that we’re being a little creepy. We move on, past a table of gun racks fashioned from deer hooves. We are both collecting whatever free swag we can get our hands on, such as complimentary Hershey’s Kisses, notepads from a company that sells flesh-eating insects to clean flesh from skeletons, and an enormous book that profiles award-winning hunters. We walk back to the hotel, enter over by the silent auction, and are immediately assaulted by a rancid, meaty stink. It smells, I am sorry to report, like a dirty menstrual pad. “Like carcass,” Maya says with grim authority. Something is rotting somewhere. Our noses adjust and soon we can’t smell it, which is equally disturbing.

The immediate question is whether or not to attend that evening’s picnic at the zoo. Soon a fleet of yellow school buses will pull up to the Best Western and drive folks over to look at some real, live animals. The zoo also houses an extensive taxidermy collection, upping the allure for this crowd. We walk over to the ticket booth, where I spot none other than Cindy Crain. I get flooded with excitement, like she’s a big celebrity, which she sort of is here at the Best Western. Her photo did not exaggerate: her hair is giant and bleach-blond; she is hung with gold jewelry and moves with a mincing strut, taxidermy’s Mae West. We catch each other’s eyes. “I love your column!” I gush, wondering if this is even true. It feels true in the moment. She gives me a weak, suspicious smile. My first request for a press pass to this event was rejected on the basis that I might be an animal rights activist looking to fuck shit up. It was rejected by an NTA employee named Cindy and I can be reasonably certain that this is her. I don’t think she’s convinced of my benevolent—or at least neutral—intentions. I smile wide, hoping to crack that tanned face, that frosted pink mouth, into a friendlier expression. It doesn’t happen. I turn to the woman at the ticket booth. Her name tag reads Cindy’s Mom. “How much are the tickets to the zoo picnic?” I ask her. She hesitates. “Five dollars,” she says. Perhaps she would rather we didn’t go, me and Maya, but she can’t really prevent it. “Five dollars!” I say to Maya. “For the zoo, the picnic, and the bus ride! We can’t afford not to go!”

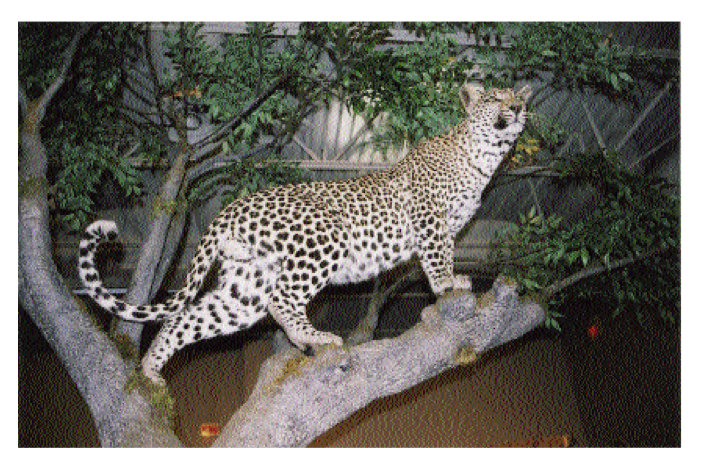

Which is how I come to be, an hour or so later, gazing in stupefied awe at a goatlike animal native to Tibet, the argali. Posed in a sparse diorama alongside other taxidermied beasts of its region, it is a noble animal with the most insane horns; dense, wide horns that curl far down its neck like the luxurious female hairdo of another era. An informational plaque states that the horns account for 13 percent of the argali’s body mass. I decide the argali is my new favorite animal. Some men cluster to my right, also studying the animal. Like everyone here at the zoo-slash-natural-history-museum, they are from the taxidermy convention. It is after-hours and we rule the place.

“Can’t hunt in Tibet,” one guy says wistfully, shaking his head. He loves the argali, too, so much that he wants to shoot one and is sad that he can’t. This is strange to me. I try to understand it. Perhaps it is like flowers. I see a pretty flower growing somewhere, I want to pick it. I want to own it, I guess. Maybe the guy wants to own the argali. But why not try to have one as a pet? Too much bother, the way caring for the plant is more hassle than simply clipping a bloom? I move away from the men. I can understand the urge to create from the pelts of slain animals, but the urge to take one down still makes me uncomfortable. Maya sidles up beside me as I look at a dusty giraffe. “I’m ready for some live stuff,” she says, and we follow the confusing signs that lead us out to the zoo.

The first pen is a stone wall enclosing a trio of heat-sick pronghorns. They sit plainly in the sun, hyperventilating, one of them rather violently. A young boy hangs himself over the rock wall to get a closer look. “I’ve never seen that live,” he says. I breathe in the smell of pronghorn shit, finding I much prefer it to the cold chemical smells of preservatives and rot. But the pronghorns inevitably make me sad. Are these my animal choices? Poorly captured or skinned and reconfigured? Of course not. There’s also Animal Planet and the Discovery Channel.

The indoor enclosures provide shade, but still there is the stifling heat. Gibbon monkeys sit listlessly in their bare, cinderblock habitat. It looks like a bad institution, monkey jail. “There is nothing alive about them,” Maya marvels. “If I saw them at the competition I’d be like, that’s a really bad mount.” She shakes her head at the dusty plastic vines decorating a bird environment across the way. “I cannot believe they have fake plants in here.” A ground squirrel dashes into the gibbon cage and nibbles at a banana smooshed into the floor. Soon there is food served, an American cookout with hamburgers and hot dogs, cole slaw and lemonade. Large speakers blare jungle noises and employees from the Best Western, clad in subdued safari costume, walk around collecting dirty paper plates. The food is delicious, but again, maybe we’re starved. “Look,” Maya nudges me. At first I think she means a hot safari worker in tight pants. “She’s the Chloë Sevigny of South Dakota,” I say. “No, them.” Maya redirects my attentions to a mother-daughter couple eating alone at a picnic table. There is a strange, withdrawn sweetness about them. At a conference where everyone clearly knows each other, mingles and joshes and shoots the shit, these two seem set apart. Nobody talks to them. The girl, a teenager, has a blunt blond haircut and an Amish vibe. I saw her shyly manning a latex turkey head booth at the trade show. Her mother has a curly brown hairdo, streaked with gray, cut short and modern. She wears a crisp denim shirt and capri pants. They look different, the way I imagine we do.

The Mayor of Sioux Falls shows up to thank the taxidermists profusely for coming to his city. He plugs Mount Rushmore and leaves the mic. Maya and I stroll the grounds, spotting tigers and snow leopards, flamingos and red ibis, goats and cows. The heat has wasted us; we’re happy when the school buses return to take us home. A bad night’s sleep, an early awakening with no caffeine, and an exhausting, scorched day. We sprawl on our respective doublewide beds and fall asleep to reruns of The Daily Show.

*

Today I take no chances with caffeine. I arrange for the hotel shuttle to drive us to a Starbucks. The nearest is at a Sheraton, and I am deflated to find it is not an actual Starbucks but a hodgepodge hotel gift shop brewing weak pots of Starbucks-brand coffee. I get a big one anyway, and in the van on the way back Maya slips and mentions that she’s majorly queer. I slap her leg and she slaps her hands over her mouth. The driver turns and looks at us. “I’ve heard worse things,” he says. He seems sort of homosexual to me, but I expect by the time

I leave this place the gnarliest hunter will have come to resemble a Village Person. It’s what happens when I’m in hiding and out of my element. My brain struggles to queer up my environment.

Slightly caffeinated, with a chewy hotel bagel tucked into a Styrofoam hamburger container, we hit Jan George’s seminar. Jan George is a lady taxidermist, a friend of the Jan whom Maya studied with in Michigan. Her seminar is titled Interactive Turkey, and when we enter the room I see a woman with fluffy, permed hair, wide eyeglasses, and a light blue polo shirt wielding a giant pair of pliers. Before her is a headless turkey, splayed out on its back, its wings stretched into wide, feathered bowls. Its thick and scaly turkey legs stick straight upright. I set my breakfast down next to a teenage boy who is perhaps sleeping, his head plunk on the desk before him. In front of me is a man in a God Bless America T-shirt. “What I’m doing here is I’m pushing these feet down flush,” Jan says, lifting the bird and setting it into a faux rock base.

“I gotta see this,” says a dude in a Van Halen shirt, who gets up and bounds onto the stage next to Jan for a close-up. After all, this is Interactive Turkey. An old woman helps Jan with the wings, which are twisted around “like a steering wheel” until they make a sickening click. The bird is upright and looking more Ichabod Crane than ever. Jan is holding a freeze-dried turkey head mounted onto a foam base.

I saw the freeze-dried turkey heads at the trade show; in their natural state they are drained of color, shaded dead winter hues, brown and beige. They are then painted the insanely vibrant colors of live turkeys—impossible blues, vivid crimson. Jan takes a paring knife and slices the protrusion of foam at the base of the head so it will be flush with the neck. She slides the head onto a wire jutting out from the form. Et voilà—a turkey.

When the audience files out me and Maya bound down to the stage and speak to Jan. “I wanted to be a vet when I was a kid,” she says. “I even started out, I took pre-vet for one year. Then I got mono and I had to drop out and I never did follow through.” She taught herself taxidermy from a book, entered a competition on a whim, and surprised herself by winning an award. I ask her what she likes about taxidermy. “Just making it look like it did before it died. And that it didn’t go to waste. That it didn’t just get skinned and eaten.” I think that I eat turkey more than any other animal. And if I were asked to conjure an image of turkey in my mind it would be the pepper-encrusted loaf behind the deli case. It would not be the breathtaking, magnificent creature arranged before me. The turkey’s feathers are relentless. They are aggressive; they sprout from the body in different styles and angles. The feathers are brown but in the light they have a bronzy iridescence. I think I understand why Native Americans wore headdresses. How could you share the land with such an animal and not want to emulate it? The magnificence of tail feathers. The bizarre droop of what looks like thick hair from between its breasts. Astounding.

I ask Jan the one weird question on my list, inspired by a conversation Maya had with a boy she’s dating, about whether you find your occupation sexy. The boy, a motorcycle mechanic, thinks his work is very sexy, and truly both mechanics and motorcycles occupy key places in the culture’s sexual psyche. But taxidermy? Maya has been musing on it. I myself think indeed it is sexy—it is posing at you, asking you to believe the beautiful illusion it is putting forth for your purely aesthetic pleasure. It is mysterious and dark, objectified and a little scary. Sounds like sex to me, but then, I was raised Catholic. I ask Jan if she thinks there’s anything sexy about taxidermy.

“Yeah, me!” she crows and flexes. “See my biceps?”

“Oh, you ought to see us in the shop with the doors locked,” her husband Brent says with a wink.

*

Our first day in Sioux Falls, my plan was to simply walk around and observe. Today I go in for the kill. Today I will interview Cindy Crain. I will not be intimidated by her sass and her sparkle.

Cindy is from Louisiana. She “married into” taxidermy, meaning her husband was a taxidermist and she has come along for the ride. In addition to being an employee of the National Taxidermist Association and penning her column for Outlook she does some writing for Safari Club International. Cindy speaks poetically about the power of taxidermists. “We are movers of skin,” she says breathlessly. “I consider myself a caretaker of animals. I consider myself a steward.” I ask her what she does to take care of animals, and she tells me about holding “sensory safaris,” where blind people get to run their hands over the forms of taxidermied animals, getting a sense, perhaps for the first time, of what the animal looks like. “That’s great,” I say, “but how do you caretake animals?”

“When a client goes out on a hunt, they come back to us as artists and they trust us with the trophy,” she explains. “When we mount an animal, we are the caretaker and the steward of that animal.” She smiles. I get that sense, as I got from the men admiring the argali, that an animal is more meaningful to these folks dead than alive, or at least that an animal’s aliveness is nothing special, is perhaps even a barrier to their adequate caretaking of the beast. “When that client looks at that finished piece of art we want it to be a good memory,” she continues. “It might be a daughter’s first deer. We want to have that family memory forever. When you stand back and you look at a finished mount you want it to tell a story without ever having to open your mouth up. You can look at something and no one has to say a word because it speaks for itself.”

OK, but is it sexy? “I tell you what,” she responds. “I’ve seen some taxidermists that are sexy. There is nothing more appealing than a man that is in camouflage or NASCAR suits! What else is there but turkey hunting and fast cars? But it’s not all about looks, it’s about what’s inside.” Truly, I love Cindy Crain. I ask her about animal rights, a subject that makes most taxidermists bristle. “If they had their way you would not own pets,” she says, echoing Tia. “You probably wouldn’t be able to drink milk. A lot of the same people who complain about hunting and fishing, they don’t think nothing about driving to McDonald’s.” I nod my head. It’s true. Though the urge to kill an animal can and does disturb me, it’s not like the meatballs I eat grow on little meatball trees. I know this. I can’t judge a person for shooting his or her dinner. I’ll reserve my judgment for those who hunt for pure sport and trophy, but the ones who kill what they eat I exempt. I’m happy to have carved out this little moral area for myself. I have felt, at this convention, ethically adrift. At one point in my life I wore only synthetic fabrics and protested rodeos. It felt great to have such convictions. But as life reveals its complexities, as the real lack of balance between humans and animals, humans and nature, becomes undeniable and seemingly irreparable, a moral stance is increasingly elusive.

If I really want to talk about animal rights, Cindy’s got the man for me. She calls over John Janelli, a former NTA board member and part of the association’s inner circle. John is a big man with a wet lisp who hails from New Jersey. “My philosophy has always been on human rights,” he says, immediately fired up. “Our basic human rights and freedoms. We’re living in a country that kills millions of unborn humans a year. We’re living in a day and age of homosexuality and all kinds of different lifestyles. Taxidermists today, we are really interested in basic human rights and freedoms.” I don’t understand how a person interested in basic human rights and freedoms can take issue with a person being a homo, but much of America does not trouble themselves with this apparent contradiction. Plus, with John’s steamroller narrative there’s not much gap for questions.

“Do we want to see everything killed?” he asks. “Certainly not. We pursue the balance of wildlife in the world today.” He goes on to list which American presidents were avid taxidermists, naming Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson. “Did you know Theodore Roosevelt mounted birds in the Oval Office?” he challenges. I did not.

“As Christian people,” he says, “we have the ironclad approval of God himself. In the very beginning of time, when Adam and Eve first committed a sin, Adam picked a fig leaf—the vegetarian way out.” John clearly thinks Adam was a big pussy. “God made for them the clothing from the skins of animals!” he exclaims. “If we’re going to believe the Bible, that’s what took place. God in his compassion and mercy for his children—I believe it’s in Genesis 9—” Now John is up and off in search of a Bible. He is going to find the exact passage that promises man dominion over the animals and put this moral quandary to bed. “Look up Genesis 9!” he is hollering to a group of men nearby. A man named Wesley rushes over with a computer printout. He hands it to John. “This is what guarantees us the use of the animals without going up there and meeting God with a dirty conscience,” John smiles. “Where did you get that?” I ask Wesley, confused. “I pulled it off the computer,” he tells me. “I got a Bible on the computer.”

“But anyway,” John prattles on, “hunters share a much deeper feeling of creation. The New-Age people tend to worship the creation, while hunters worship the Creator.” It’s a good sound bite, but more than anything it sounds like arrogance, possibly blasphemous to boot, like trying to sit in the seat of the Christian God himself. I ask him if he thinks taxidermy is sexy.

“Oow!” he slaps his knee and honks like Tony Soprano. He turns to a cluster of men drawn near by the Bible commotion. “Steve, do you think taxidermy is sexy?” He shakes his head. “I can’t go there.”

Steve thinks a moment. “When my wife’s doing it naked,” he joshes.

A woman standing by Steve, who may or may not be his wife, remarks, “I feel it’s more powerful than sexy.”

Good Answer, I nod. “I don’t think it’s as sexy as much as sensual,” Steve concludes. “When I’m painting a fish…”

“Absolutely!” chimes in a man with a name tag reading Mark. Our conversation is interrupted by a man who wants to purchase a Team Jesus shirt.

John then launches into a truly bizarre rant that likens the media’s use of the word kill in regard to hunting (he prefers harvest) to the use of the word nigger in reference to black people. He is insulted that the media protects people from the N-word by listing it as n—, while flagrantly using the K-word—a word, in John Janelli’s opinion, as hurtful as any racial slur. “The hunter is discriminated against more than any other race in the world put together,” he says. I feel I have spent too much time around John Janelli and I’m starting to lose my mind. I pull myself up from the armchair I was sunk in and walk off, shaking the bad vibes off me like a dog shaking off wet. I find Maya and pull her into the Mustang. It’s time for another round of quesadillas.

After lunch we hit the competition room again. In a few hours the doors will be opened and the room will flood with people. Now the judges hustle and confer, the clock ticking. We spot Stefan Savides judging a duck amid the kids’ entries. Maya wonders aloud if the kids killed the animals, too. “May have,” Stefan shrugs. “They all have hunting parents who take them out hunting as soon as they’re able to shoot.”

I cruise by a bank of deer mounts and meet a mustached deer judge named Fred Vanderburgh. “What do you think of that one?” I ask about a deer head mounted beside a wreath of rusty barbed wire. A shred of material is snagged on a barb; the deer appears to be sniffing it. Below it, spelled in wire, is the word Intruder. “It’s a little tacky,” Fred admits. “There’s a hunter in the area, is what he’s trying to say.”

I find Maya mesmerized by a giant turkey. I dismiss the argali and decide that turkeys are absolutely my new favorite animal. They are spectacular. “This reminds me of a fat drag queen,” Maya says. “Like Divine.” Maya crouches down and strokes the bird’s sturdy pink legs. “You’ll never get to touch turkey legs again,” she says. I join her. We hover over a sign reading Please do NOT touch mounts, fondling turkey legs.

Behind us a gang of judges are working together to determine the Best in Show. “Do we all agree that the quail is No. 1?” a man asks. Stefan Savides shakes his shaggy head. “I’m not there yet.” They move on to consider a grouse, its neck feathers puffed up to form a fierce-looking black heart. It looks like a glamorous baby dinosaur. “There isn’t anything that isn’t busy about this piece,” Stefan complains. “The grouse is busy, the birch is busy,” he points to the birch trim on the pedestal.

My gaze swings upward to the underside of a giant mountain goat, mounted on rocks and hung on the wall. I have walked by and admired the piece more than once, but never had I caught it at this angle. “Oh my god,” I say. There is its rather large, taxidermied penis. Maya follows my gaze and laughs. “I love stuffing balls,” she says. “I try to make them as massive as possible. You should see my fox. His balls are massive.”

*

It’s our last day at the convention and I say to hell with passing. To hell with my layers and layers of hot clothes, my smooshed-down, lifeless hairdo, my dull face. I twist my hair into twin pompoms on my head and slick my lips with gloss. I wear a thin T-shirt that exposes my arms and their many tattoos. I wear flip-flops. Maya stares at me. “What the fuck?” I say philosophically. “Who cares?” But the reactions I get are quite different from those of the past couple of days. Though I looked a little off-kilter, my attempt at modesty was rewarded by the others: they overlooked me. Now I get stares, some curious, some hostile. Cindy’s Mom grabs my decorated arm with her elderly hand as I pass her in the hall. “What have you done to yourself, child!” She gives me a severe face.

Maya and I spend our last hours before the airport shuttle shopping for souvenirs at the trade show. I contemplate bringing a taxidermied chick home to my boyfriend but am afraid it will depress him. He really loves chicks. I don’t know if that means he’d love or hate a taxidermied one. I settle instead for some death masks of various birds. A bin holds a jumble of messed-up ones, six for $5. I go to work pulling out my favorites while Maya haggles with the proprietor, a glum, skinny man in flannel and a baseball hat, to come down on the price of a turkey head.

“Look!” Maya spins me towards the back wall, where the mother-daughter team with the aura of innocence sits at their booth, a display of latex turkey heads arranged on the table before them. “You’ve got to interview them,” she urges. So I do.

They are Kim and Carolyn Kuenzel. Carolyn is seventeen and Kim is her mother. They recently moved from Washington, D.C., to Fayetteville, Arkansas, when Kim’s husband, a chicken neurologist, got work at the local university. All Kim’s urban friends told her she was crazy to head into the backwoods part of our land, but she’s taken to it quite nicely, and Carolyn nods her head in humble agreement. They raise chickens for meat and eggs and Kim makes taxidermy art with what is left over. She took over this latex turkey head business they’re representing at the trade show, which is their first.

“In D.C. it was kind of a brutal climate for being a woman,” Kim tells me. “Here they open doors, they carry things. It’s a very gentle lifestyle. Which is odd because they’re running around shooting things.”

Me and Maya’s mysterious attraction to the pair becomes understandable as we converse. Like us, they are outsiders at the convention. “We’re a different religion than they all are,” Kim says, nodding to the masses milling about the trade show. “When it comes to the banquet tonight, they’re going to play the national anthem, and in our religion we’re not allowed to stand up for it. We’re Jehovah’s Witnesses. We stay politically neutral. We do not participate in politics at all.” Kim explains to me that they believe the current government is bunk, that eventually God is coming down and instituting the real government, and that they’re just going to sit it out ’til then. I’m terribly jealous. I hate our Republican administration so much, I deeply wish I could believe in a religion—or even a viable Democratic candidate—that promises its days are numbered. I ask Kim if she feels frustrated that she’s unable to participate in the political process, and she shakes her head serenely. “I wouldn’t touch the political process at all,” she says. “People do all this political wrangling and I think, you would be so much more balanced and peaceful if you realized it couldn’t be fixed.”

A young, hotshot waterfowl taxidermist, Cody Ballanger, strolls by the booth for a chat. Cody is one of the taxidermists the BBC followed around the recent World Taxidermy Championships for their documentary. They discuss the pitfalls of taxidermy. “Fleshing is by far the worst,” he says. His hair is longish and tucked into a baseball hat. “Do a Canadian goose eider, they’re quite disgusting. They’re fatty and you look like a greaseball when you’re done fleshing it.”

Kim tops him easily. She holds up a thoroughly scabbed finger. The skin is deflated, like it’s collapsing on itself, and a Frankenstein stitch zig-zags through the middle. “That’s what happens when you inject yourself with Masters Blend, eight days later.” Masters Blend is an epoxy used in taxidermying big birds. It heats up to about two hundred degrees. “It cooked it from the inside out. Twenty-four hours later I had to go and have it looked at. They had to cut it open and butterfly it. It’s dead as a doornail,” she shrugs. “I haven’t felt a thing since I did it.” She is incredibly calm about this. It’s probably the religion.

In addition to working with the birds they kill for food, Kim and Carolyn both taxidermy other animals, road kill they find or songbirds they get from a university colleague with a songbird permit. “We’re not hunters,” Kim says. “We’re still city folk. I have never reconciled myself with killing anything. My little birds are handheld, I do it very humanely. They don’t flop, they don’t panic. I can’t just kill an animal.”

Carolyn nods solemnly. “I do not like killing the rabbits,” she offers. “Sometimes they squeal. When you kill them, they squeal.”

“You’re in California,” Kim says, “so there might be a lot of people who believe the killing and eating of animals is bad.” I nod my head. I tell her how I used to be a vegan, a

vegetarian, an animal rights activist. “Well, you look like one!” she

exclaims. “When I saw you I thought, uh-oh, PETA’s gonna interview me!”

“See what I told you?” Maya says. I guess it is good that I wore the layers for the first two days.

“What changed for you?” Kim asks me. “Why did you stop?” I have to think about it a while. It wasn’t an overnight shift, more like a gradual confusion that neutralized my intentions. I realized my body works best when I give it meat. I realized we are so out of balance that trying to figure out the most ethical way to be, regarding animals, is a joke. I don’t like animal cruelty or factory farming, and I try to eat only organic, humanely raised meat. It is a terrible mystery why I feel compassion for the animals that die to feed me. It is the mystery of being human. I realized the question is too big for me, and I let go of trying to answer it.

Kim smiles at me. “Sounds like you’re almost where us Witnesses are at.”

*

One week later and I’m back in Tia Resleure’s Victorian taxidermy paradise. I’m telling Tia about my conversation with John Janelli.

“I think you got something going with born-again Christians—low-brow Christians—that whatever they get into, it’s going to be fucked-up because they’re Christians.” She cites a born-again Christian who loves Italian greyhounds and fucked it up by creating a Canines for Christ organization. But mostly Tia defends the traditional taxidermists I talk about, even the nuttier ones. They were made that way, she asserts, by the animal rights activists. The attacks of the animal rights people have created a paranoid, high-strung personality type among the taxidermists. Tia tells story after story illustrating how the overreactions of animal rights people have hurt innocent animal-lovers. Bereft Las Vegas show orangutans taken from their owners; homeowners driven mad by raccoon infestations finding themselves in jail for animal abuse; her own son nearly doing time for “abusing” his dog, which had only fallen off the bed. Each story tops the last, and Tia becomes increasingly agitated. She cites legal decisions to not re-release quail into public parks because the feral cats would eat the eggs, and how the animal rights people would fight the euthanizing of the feral cats. It makes me dizzy. It is not natural that the cats are there, no. But it is not natural that we are where we are, we humans, in the way we are. Who’s to say what is natural, now, at this late hour?

The tension is cut by the skittering entrance of the Italian greyhounds. One dashes over to Maya, who fondles his pointy ears. “He’s a reject show-dog because of his ears,” she says.

Tia nods. “Erect ears do not make for an aerodynamic dog. But he doesn’t care, he’s happier.”

We rise from the table, still laden with taxidermy in various states of deconstruction and wholeness, and move downstairs to Tia’s basement. Today Tia and Maya will make a carcass cast of an Italian greyhound, and I was invited to observe. Tia’s basement is a small, low-ceilinged workspace. A dog skull bobs in a bin of rainwater outside the entrance. There’s a long strip of canaries, encased in plastic, from when Tia worked at a pet shop. “Every time a canary would die I would throw it in the freezer,” she laughs.

The defrosting carcass sits on the cement floor, in a corner. It is inside a plastic bag inside a paper bag, and the paper bag, soaked through from the melt inside, rips when Maya lifts it. She brings it over to a table, and Tia splits it open. She recoils. There is real horror on her face. “Oh my god,” she says. “I pulled out the wrong dog.” She looks down at it, then up, and shakes her head. “It’s Bis,” she says. “Bis was my favorite Italian greyhound. Fuck!” She is distraught. “Maybe I should put her back. I don’t want to fuck her up. Oh, Bis.” She shakes her head. “I had to put her to sleep last Christmas, she was falling down the stairs.”

The two artists get to work refreezing Bis and digging out the animal they’d meant to thaw, a frozen hunk of skinned dog, ruby meat and muscle, sparkling with ice. They rearrange the contents of the freezer. “It’s not good to thaw her out and then freeze her.” Tia worries about Bis. I spy many little bags of frozen kittens. “Those are the ones from the pregnancy spay,” she mentions to Maya. “It was a big litter.”

At the other end of the cramped room, in a pile of salt on the floor, are what look like two long, stiff hides and a couple of smashed and scaly other things. I ask Tia what they are. “Cat heads,” she tells me. “Its ears are inside out. Roadkill.” They look maybe like destroyed, dried fish, the wide mackerels hung in Chinatown shops. Maybe they look like salted jerky. What they do not look like are cat heads, and it’s amazing that these scabby messes will someday be the sleekly furred, repaired pieces of taxidermy I’ve seen in Tia’s home and elsewhere. Seeing the degraded state the pelts are reduced to, and their ultimate rejuvenation into passably living animals, it’s less of a wonder why taxidermists wind up feeling like they reanimate these animals; re-creating the Creator’s creations.

Tia and Maya investigate the icy carcass. Its skinned head is tucked, a single fang protruding from its mouth. Maya taps its neck. “She’s frozen solid.”

“She looks like a Pompeii victim,” Tia comments, and it’s true. “You know they have that really famous dog caught in Pompeii?” Maya pounds the dog gently, strokes the tiny whip-tip of its hard, pink tail. It’s amazing that it retains it dogness, its twisted cuteness, despite its lack of skin, its excess of red and meat. Tia and Maya rebundle the dog in plastic and place it on the cement floor to melt.