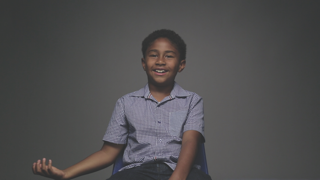

The children of Silicon Valley tech workers—the preadolescent offspring of Apple engineers and Cisco consultants, restaurant cooks at Google and PR managers at tiny start-ups—sit dressed in dark jeans and freshly washed hoodies, describing the world as it will look and feel seventy or eighty years in the future. The questions that prompt these predictions come from behind the camera in the bemused, encouraging voice of the filmmaker Mike Mills. Mills asks the kids about their relationship to technology and how it will shape the world they’ll inherit: will there be more or fewer poor people in the future? Will people be smarter? How will nature change?

The children’s answers are charming—as any speculative conversation with a curated group of eight- to eleven-year-olds is bound to be—but as they raise questions about the environmental, economic, and social legacy of Silicon Valley’s comprehensive influence on their lives, their predictions take a darker turn. The film, A Mind Forever Voyaging Through Strange Seas of Thought Alone, was commissioned by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and appeared as part of a temporary installation Mills created in a vintage costume shop in Los Altos, California, where he also produced a broadsheet reprint of a 1976 issue of the Los Altos Town Crier combined with “official documentation of the formation of the Apple Computer Company.” That exhibition closed in March, but the film is now available to Believer readers through May 1, 2014 at believermag.com/mikemills

Mills, whose feature-film credits include Thumbsucker and the Oscar-winning Beginners, started his career making experimental documentary shorts like Deformer and Paperboys (about skateboarder and artist Ed Templeton and a group of Minnesota paperboys, respectively). As Jennifer Dunlop Fletcher, the SFMOMA project’s curator, points out, A Mind Forever Voyaging is a part of this lineage of portrait films, and like those two early shorts it offers “an empathetic view of suburban America” in its current iteration.

This conversation between Mills and Gideon Lewis-Kraus occurred during his recent visit to San Francisco for a screening of the film.

—The Editors

THE BELIEVER: What one immediately notices in the film is that this is a pretty ethnically diverse group, but it seems, given that one knows this is taking place in Los Altos, that they’re pretty socioeconomically homogenous. I counted just two working-class jobs among the parents, and I’m curious how you made those decisions about casting and what kind of group of kids you wanted to come up with.

MIKE MILLS: Our rule was that the parents had to work in Silicon Valley. And most of them lived around Los Altos, but...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in