Claude Cahun is known mostly for her 1920s “autoportraits,” photographs that show her playing roles such as androgynous alien, flamboyant boxer, mirror-gazing dandy, masked goddess, and mistress in curls. She participated in Surrealist exhibitions and her signature can be found on several of the movement’s manifestos, but Cahun—née Lucy Schwob, before her androgyne rebirth—really was her own movement. She was joined by the artist and designer Suzanne Malherbe, her nearly lifelong collaborator, lover, and later “stepsister,” who went by the name Marcel Moore. Their lives together were devoted to fearless activism, performance, and avant-garde theatre. While living on the island of Jersey during the German occupation they launched a two-woman resistance against the Nazis over the course of two years, distributing poetic tracts of transcribed BBC radio broadcasts that encouraged insurrection to German soldiers. This eventually led to their imprisonment, and they were briefly sentenced to death (commuted against their wishes).

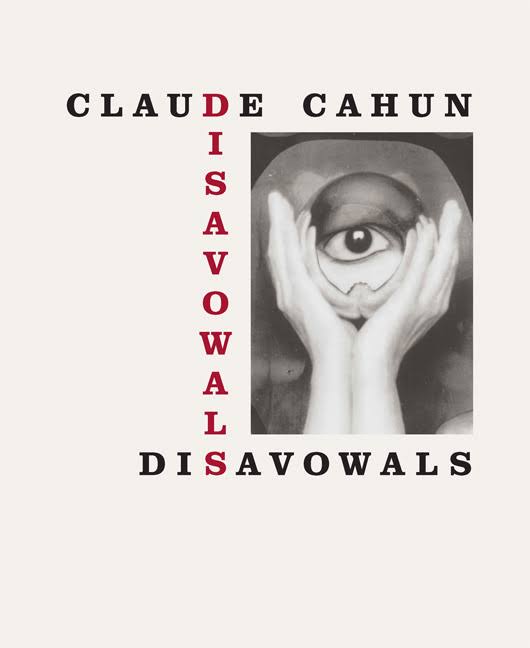

Cahun’s main literary text, an anti-manifesto of sorts called Aveux non avenus, was published in 1930 with a print run of only five hundred copies. After its disappointing reception, Cahun lamented that no one wanted to read “the prose poems of an unwanted Cassandra.” She mostly lived and worked in obscurity, her temporary imprisonment a metaphor for her relative lack of recognition in her lifetime. Aveux non avenus speaks of this confinement, referencing the “Oubliette,” where prisoners are forgotten. This collection, which Pierre Mac Orlan describes as “poem-essays and essay-poems” in the original introduction, reads like an inquisition of the self and female identity. These are Cahun’s confessions (“Aveux”), relentless interrogations of the prison and prisms of identity, but they should not be entirely trusted. Non Avenu is a legal term meaning “null and void,” and while English-language editions are published under the title Disavowals, there is the alternative Cancelled Confessions, and Cahun herself translated the title as Denials.

It follows that this in not an “autobiography” in strictest terms. At two hundred–some pages, written over ten years, this book is far from anything resembling a novel, or even a narrative. Divided by photomontages of Cahun’s self-portraits, this is a collection of fragments grouped around various aspects of the self, a type of persona writing that foreshadows Kathy Acker. Cahun speaks with the voice of the transgressive, much as she does in Heroines, a series of monologues published in part in 1925. With an encyclopedia of references, she identifies herself as characters such as Salome (Oscar Wilde’s version), Eve, Eden’s snake, Medusa, and Narcissus. “Individualism? Narcissism? Certainly. My best characteristic, the one and only intentional fidelity I am capable of. You don’t care? I’m lying anyway: I scatter myself too widely for that.”

Much of this book seems written in code. There are childhood games, wordplay, and elaborate punning almost impossible to translate, aphorisms and Bible proverbs twisted inside out, a suicide note mocking formal French convention, dream narratives, Freudian nightmares, snatches of conversation, parables, provocative musings about God, and an obsession with a man named “Bob.” The result is a refracted mirror. Reading what Cahun calls her “Byzantine work” is like winding around the labyrinth of a fascinating and always elusive self, a dissolution as opposed to a composition of identity.