At its best, the celebrity profile fosters a feeling of warm intimacy. We read the profile, and we feel we have been granted access not just to the contents of the celebrity’s overnight bag but to the contents of his or her heart. Yet this same profile simultaneously manages to reveal no new information. We love it because it confirms our best beliefs. No other form so seamlessly constructs the necessary components of celebrity, exploiting the desire to see our idol as both “just like us” and nothing like us, as both the girl next door and a goddess above. It is, in other words, spectacularly banal.

Yet the celebrity profile serves a crucial industrial function: it sells the media products in which the celebrity appears; it sells the magazine that publishes the profile; but, most important, it sells the celebrity’s image and the values that image is made to represent. A profile of Robert Downey Jr. labors to reinforce the central tenets of his image (the phoenix-like return, the affability, the specter of his party-boy youth); a profile of Jennifer Lawrence convinces us that the joking, off-the-cuff, cool-girl charisma we see in her post–Oscar win interviews is not a performance but her authentic self. Each profile is almost eerily on message: Ryan Gosling is introspective; George Clooney is charismatic.

The trick, of course, is to make it look like the profile is not selling anything. It’s just a chat between friends, or a nonchalant trip to the desert to get tipsy, engage in some “real talk” that sets forth the celebrity’s most winning attributes, and meander to a discussion of his or her upcoming project. This elision is crucial to the celebrity process writ large: we want to believe that these celebrities give of themselves willingly, not because of economic imperative.

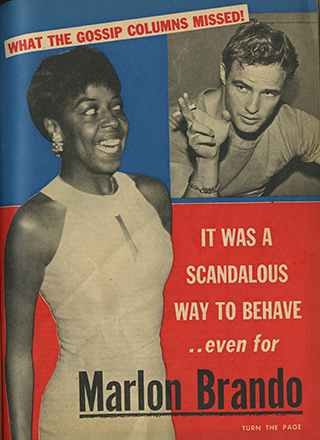

These tensions within the celebrity profile—selling oneself versus erasing evidence of the sale, generating intimacy while disclosing nothing—have structured the profile for decades. And the profile of the late twentieth and early twenty-first century enacts a return to the publicity style of classic Hollywood, when the studios found raw “star material” in the form of pliable young talent, packaged it, labeled it with prefabricated type, and sold the star in a meticulously mediated bundle to the American public.

*

In classic Hollywood, the publicity apparatus—fan magazines, gossip columnists—worked in concert with the studios. A profile was constructed using biographical sketches provided by the studio itself, mixed with quotes the star may or may not have provided, and thoroughly vetted, before making its way to audiences. For example, a 1928 Photoplay profile of silent-movie star Clara Bow, “as told to” Adela...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in