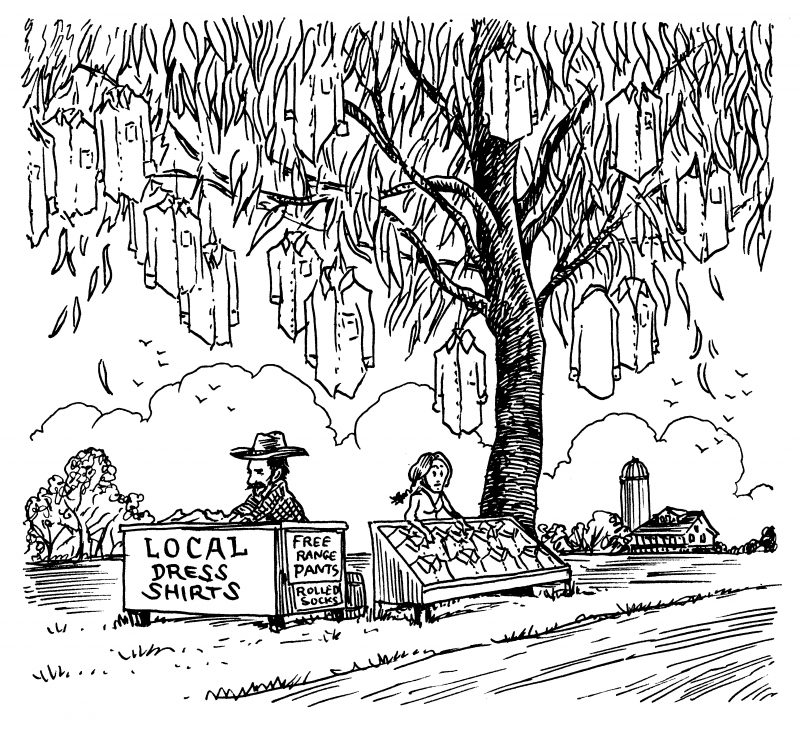

There’s a nascent conscientious-clothing movement, but it’s several years behind the one for food. Michael Pollan’s food writing changed the way I eat. Before, what mattered to me were taste and price, and not even taste so much. I ate mostly take-out Chinese and fantasized about alimentary pastes. Now I’m a militant flexitarian, and worship at the farmers’ market. Pollan is now an era—so popular you don’t actually have to read his books. To be sure, many of his ideas about the problems with how we get our food, and what we might do to fix things, were well and widely expressed before, but Pollan came at the right time with the right tone. His rules (“Eat your colors,” “Pay more, eat less”) can be implemented without a major lifestyle change.

What I want to know is this: where are the Michael Pollans for clothing? They must be out there, writing book proposals. In fact, a journalist named Elizabeth Cline has a book scheduled to be published by Penguin Portfolio in the spring of 2012 that was sold as “the Omnivore’s Dilemma of clothes.” Fashion has parallels to food: most clothing is too cheap, that cheapness has tragic costs, clothing is an agricultural product, and we consume too much of it. Affordable designer collaborations are like the rise of the home gourmet, but now we should be ready for responsibility beyond taste and design. I’m looking for the textile version of Food Rules, some aphoristic guidelines that won’t make me feel evil when buying a shirt (though I like at least a little guilt with every transaction). Show me how to spend wisely and conscientiously. Does a made in usa label mean better made? More ethically made? Or just more nationalistic? How about a union label? As a recovering bargain-hunter, I would like to know what a reasonable price is for a men’s dress shirt. Not a good deal, but a fair deal. A price that hasn’t factored in extraordinary human pain and economic distress and environmental destruction. A price that’ll help sustain responsible craft and industry.

I’m looking for a centrist buying guide. If you offer an extreme solution, like a cult that makes excessive demands, you’ll get extreme followers. Those followers will be enthusiastic at the start, but unlikely to stick with the plan for long, and won’t be good for recruiting the more stable masses. For example, a call to buy all clothing at thrift stores might be ethically defensible, but you’re crazy if you think everyone—professionals, workers, parents shopping for back-to-school outfits for their kids—will commit to second-hand stores. They just smell too weird for most. Sizing would be a problem. Plus, the global economy would collapse and we’d run out of clothing pretty quickly. (Admittedly, I also wonder what would happen if everyone started shopping for fruit at the farmers’ market, or getting their books from the library. Maybe it’d be fine, and these institutions would expand, and our expectations could contract.)

Cheap: The High Cost of Discount Culture by Ellen Ruppel Shell, published in 2009, is a stepping-stone to an enlightened buying guide. Ironically, the Times quote on the front of my copy, “Pay full price for this book,” is obscured by a Strand discount price tag. In fact, Shell tells how Philadelphia department-store founder John Wanamaker invented the price tag because he believed that as all were equal before God, so should all be “equal before price.” Before the price tag, there was more haggling, which required more knowledge about the market and what you were buying. And this buying and selling were generally done within a community—so if you screwed somebody from either side of the counter, it’d come back to haunt you.

But it’s hard now to be deeply knowledgeable about clothing. We’re specialized, and the clothing industry is opaque. You can plant a tomato or raise a chicken, but most of us can’t grow and process enough cotton to make sweaters, or become boot makers by reading a few articles. What—now I’m supposed to care if the buttonholes on a suit sleeve are functional, even if I don’t wear suits outside of weddings? I heard a story that haunts me about how a storied tailor, which sells its suits to a high-end clothing line that hipsters trust, laughs because it sells the hipster designers its junkiest stuff, and the hipsters don’t know any better. It’s tough to play catch-up in any field, like learning a language late in life.

Now, if you’re going to start doing anything because you think it’s the right thing to do, or you’re going to advocate for a better way of doing something, you have to be prepared for some blowback. Watch what happens when celebrities take up a cause. If you follow 75 percent of a religion’s creed, people will ask accusingly about the other 25 percent, especially when they’re following 0 percent. If you become a vegetarian, someone will point out rough conditions at soybean farms. You might hear that the Prius is a pose. Some say Whole Foods is mostly image—a way for people with more money to feel better about spending it. I have to think that some effort is better than none. For the most part, I believe in what Whole Foods is doing; it even has plans to implement a 1–5 ranking system to describe the conditions under which the animals used for meat and dairy were raised—from 1 (“Acceptable”) to 5 (“Gold Standard”). It almost sounds like a psychology experiment. And you better spring for the 5, if you can afford it, even when you’re not trying to impress a potential romantic partner.

cotton dress shirt, $24.99–$29.99.

I have the “Eat Humane Food Guide” app, by the World Society for the Protection of Animals, but it’s far from comprehensive, as it currently lists only ten restaurants in or near New York. “Free range” can be a murky category, but the “Certified Humane,” “American Humane Certified,” and “Animal Welfare Approved” labels seem legitimate. They’re like a kosher symbol for mindful food shoppers. Similar rankings are in the works for clothing, but they are a ways from being implemented. A new “Eco Index” is being collaborated on by about one hundred apparel brands and retailers, including biggies like Nike, Timberland, Target, and Levi’s. The Wall Street Journal compares the index to the Energy Star rating for appliances. For now it will be internal, from self-reported estimates. It will include a blend of ecological and human-rights factors, though it’s especially unclear how the human-rights aspect might be accounted for. It won’t be perfect, no doubt some will try to game the system, and of course the law of unintended consequences will still be in effect. As it is, brands can get points for having tags that say, “Wash in cold water, line dry, and donate to Goodwill.”

It’s easy to be cynical here, but it’s also easy to see how simple instructions like that might change the behavior of a lot of people. The Amsterdam-based Fair Wear Foundation (FWF) is dedicated to overseeing and improving working conditions in the garment industry. It inspects factories and coordinates and verifies companies’ labor-improvement plans. Mostly European designer brands have volunteered to be a part of the FWF, labels like Acne, Nudie, Cheap Monday, J. Lindeberg, and Jack Wolfskin (which is like a German North Face). But the FWF doesn’t give a simple thumbs-up or -down. Instead, you have to go to the website and download a multipage bureaucratic report for each label, which drily describes positive and negative steps on the company’s path to fair labor. For most people, merely trying on pants is a lot of work. This is a reading-glasses level of engagement that most consumers will not go through. But the program could become a helpful guide, and it’s got a catchy logo for when it’s ready to interact more succinctly with consumers.

Better than a chart or a number, always, is a passionate expert. No graph or stat can interpret nuance like a person who knows what’s what in your corner. This is partly why there’s that longing for a time when commerce was more personal, and relationships were more woven into our transactions. “What’s good today?” “Where are these from?” It took this sort of closeness to convince me to spend over $100 on a pair of shorts. (Yeah, some people don’t think adult males should wear shorts. I don’t hold by that.) I know it sounds punch-liney, but I really was raised to hunt clearance racks, and announce kills thusly: “Was: $150; I paid… $27.99!” When I was living at home after college and bought a pair of Gap khakis at their regular price of $40, my mother seemed by equal measures confused and betrayed.

But here’s the thing about my fancy shorts: They’re made in America at a factory that pays good wages! I know the guy who designed them! He’s a part of the community! This is rare deadstock real Indian madras fabric! They’re part of a “small batch”! They will only get better with time! You just can’t get a fit like this at the big chains! I love them like I could never love a pair of mass-produced shorts! I’ll wear them nearly every summer day! Isn’t it better to buy one great pair than four blah ones? Less landfill! They’re not just making me sexier, they’re rebuilding our nation! Didn’t you read Shop Class as Soulcraft? I didn’t, but a lot of people did. It’s about how we need to learn to make and fix things again, especially while quoting philosophers. This is part of that. Are they better than other shorts I have? Yes and no. I have some UNIQLO ones made in China that seem more solidly sewn, though they don’t fit as well. I don’t know if my super-shorts will last ten years, and maybe well-crafted shorts are an insane example. But why should they be? I adore them. You have to look at price-per-wear. (Or price-per-compliment.)

Again, sharing the prices we pay feels like such a personal revelation. Please don’t tell anyone how much those shorts were. It’s become a cliché that financial matters are more intimate than sexual ones. (This is why The Price Is Right has stuck around for so long; just try to watch some clips on YouTube and not get emotionally involved.) I mentioned to an acquaintance that my favorite store had cool jeans for $145, which seemed fair since fancy jeans averaged at least $200 during the early 2000s’ “premium denim” boom years. She was shocked, and said she’d never pay more than $45, and usually less at a secondhand store. (A recent poll said the average woman spends $34 per pair.) I’ve casually but persistently asked around to figure out what people think is a fair price to pay for a men’s dress shirt or a nice Oxford shirt, and got answers from $20 to “Never less than $100.” In New York, the number hovered around $75, and in the non-Chicago Midwest it was closer to $30. (But, like in polls about sexuality, people probably lie depending on what they want you to think of them, or what they want to think of themselves.) My favorite answer was from a guy who said he was suspicious of any dress shirt that cost less than $60, and resentful of any over $125. Consumer Reports picked the $25 JCPenney Stafford Signature as the best no-iron cotton dress shirt, besting the $40 one from Lands’ End. It “assessed construction and looked for flaws in stitching or fabric.” It does not look at coolness or fit—I always find it bizarre when the magazine applies its rigorous metric to things like shirts or, especially, jeans.

Clothing is so personal—it’s like rating which state produces the best spouses. And shouldn’t Consumer Reports also take into account how, right or wrong, the brand of jeans we wear as kids affects our sense of self long after we’ve left the schoolyard? That’s not a job for a lab technician, but more for a personal essayist. That $25 to $40 range probably gives a sense of what most would consider a realistic price for a dress shirt. But I wish Consumer Reports looked at more than construction, and checked into the shirt’s backstory. Where were these shirts made? And by whom? That should be part of the report issued to any fully conscious consumer. In 2010, spending $25 for the best shirt doesn’t make sense. In the Sears 1984 catalog, the “Johnny Carson” dress shirts were $22. Adjusting for inflation, an equivalent shirt should be closer to $46 now. The question “Why pay more?” keeps getting less and less rhetorical. There are lots of reasons. I would likely shop at a shoe store called PayMore, with the slogan HaveLess.

I asked Michael, one of my connections to the fashion business, and who runs a small clothing store and label, what he thought would be the cheapest a shirt could retail for and still be ethically made. His verdict: $50 to $60, probably closer to $60. That means a wholesale price of $25. (A company like J. Crew pays $20 for shirts that sell for $60. This is not to uncover a scam—companies are in fact supposed to sell products for a profit.) Fabric production—the process of transforming cotton into cloth—is likely where a lot of ethical corners get cut. The costs for material are fixed, and good cotton is expensive, so the way to make a shirt less expensive would be to have it made ethically in Asia, where workers can live on less, even when they’re relatively well paid. It’s not just about made in usa, a country that has more than its share of shady textile manufacturing. Nau, which took some of its managerial DNA from Patagonia, a pioneer in environmentally conscious corporate responsibility, is an ethically concerned Oregon-based fashion company that manufactures outside the U.S., in Canada, China, Thailand, and Turkey, but ensures that its manufacturing partners adhere to a code of conduct that covers humanitarian and environmental issues. I have a canvas Baggu backpack whose tag boasts, ethically made in china. (Michael thinks it’s not going to be possible to make non-luxury clothing in America.)

cotton dress shirt, $24.99–$29.99.

So sixty bucks—that’s a big leap from twenty-five. And that’s for a basic, not a fancy, shirt. It’s tough enough getting people to spend two more dollars for humanely raised eggs, or vegetables instead of dollar-menu fast food. JCPenney dress shirts may list for $26 to $55—and $55 is close to our magic number for what a shirt should cost—but those aren’t what JCPenney expects to sell them for. Those shirts are always “on sale” for half of the retail price, which is, of course, their “actual” price. Almost all big stores do this. You’re not playing them by waiting for sales—they’re playing you! If you pay twenty-three bucks, figure the store paid ten. How can we go from seed to yarn to fabric to finished product for so little money? We can’t. Not without some bad things happening. Perhaps a French-style, government-mandated sale-season could wean us off our addiction to “discounts.” But as far as ethical food versus clothing goes, it seems easier to win sympathy for animals than for people.

Clothing won’t sell by being good for the world. People have to want it for what it is. Like how shopping at Whole Foods is full-on, sensual, grocery-store pleasure—there’s nothing co-oppy or stripped down about the experience. The sometimes-controversial American Apparel—I know many have their beef with the caddish ways of CEO Dov Charney—is about being cool and sexy first, and being made in America and providing full health benefits to employees second. The 2006 documentary No Sweat gives a good view of the workings of AA and SweatX—the latter a failed experiment in worker-owned textile manufacturing funded by venture capital from Ben Cohen of Ben & Jerry’s. Whatever issues people may have with AA, the company is relatively transparent about its manufacturing process. The AA factory seems bright and airy, and the benefits are impressive, even if it isn’t recruiting from college campuses, and it’s all non-union piecework. Still, it seems better than many other domestic alternatives. Should your underwear be made by an artisan? I’m really asking. Labels that put sustainability first and coolness later tend not to be at the top. Edun (founded in part by Bono) isn’t as cool as it should be, and the overtly organic Loomstate isn’t as coveted as its sister company, Rogan, which doesn’t play the environment card.

In what might be a mixture of the best of American Apparel and SweatX, a factory in Villa Altagracia, Dominican Republic, owned by South Carolina–based Knights Apparel, is paying a living wage to unionized workers. The plant is well lit, and its ergonomic chairs for seamstresses are expensive. The project is the result of an awakening the CEO had upon receiving a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. It already makes collegiate apparel for a lot of universities, so it’s starting with more momentum than SweatX. And the name of the line, Alta Gracia, is cooler than SweatX. The T-shirts will cost the company $4.80 each, wholesale for $8, and retail for $18 (which seems in line with $60 for an ethical dress shirt, which requires more of everything). So Alta Gracia won’t be producing high-end luxury goods, but it will be competing with premium athletic brands and American Apparel. Again, the brand has to be coveted because of what it is more than because of its mission. Altruistic labels can even be a negative. The fashion director at Barneys recently noted: “When we explicitly labeled Stella McCartney’s organic line with the word organic, its perceived value actually went down in the eyes of the consumer.” So it’d be ideal if Alta Gracia could be hip and well-fitting (as much as college gear can be), and the healing-the-world aspect kept more in the background. Eighteen dollars sounds doable for an ethically made T-shirt. These aren’t mere undershirts, after all; these are T-shirts, a major locus of identity, expression, and attainable art.

My ideas about how we relate to what we buy were informed by Paul Bloom, the psychologist and cognitive scientist who wrote How Pleasure Works: The New Science of Why We Like What We Like (W.W. Norton & Company, 2010). Bloom was interviewed by Sam Tanenhaus for the New York Times Book Review podcast (June 25, 2010). Bloom holds that we like what we like for reasons more complex than ideas about symmetry or chemistry. Rather, preferences and appreciation for something are “rooted in our beliefs about what that thing really is—that thing’s hidden essence.” He mentions a study in which people were fed wine via a tube while in an fMRI machine. Participants were shown information about the wine on a screen, and when they thought a wine was more expensive, the pleasure centers in their brains went wild. This reaction isn’t about pretending to like something because we’re supposed to; rather, “the experience is actually transformed.”

Here’s some insight into why I treasure my shorts so much. It’s partly why some designer labels come with an elaborate certificate of authenticity, complete with laser hologram. Higher-end boutiques and department stores, along with ad campaigns, all help build a brand’s essence. This is one reason I think advertising on the web, with its precision metrics, is a tougher sell—we don’t really know how to use the web well enough yet to stoke that essence, like we do with glossy magazine ads, TV spots, or billboards. The creation of such an essence, be it for a wine, car, watch, or shoe, is always a collaboration between the consumer and the advertiser. It can never be fully formed on either the buyer’s or the seller’s side. This is also why I get upset when people say, “You’re just paying for the packaging,” or “You’re paying for the label.” (Does anyone even say those things anymore, or are they dying generational complaints?) Discount stores generally siphon away any worthwhile essence (that’s how you save!), and therefore a product’s lovability. Who treasures the sheets they bought at Monstromart? You might boast about the deal you got, but that’s a fleeting high.

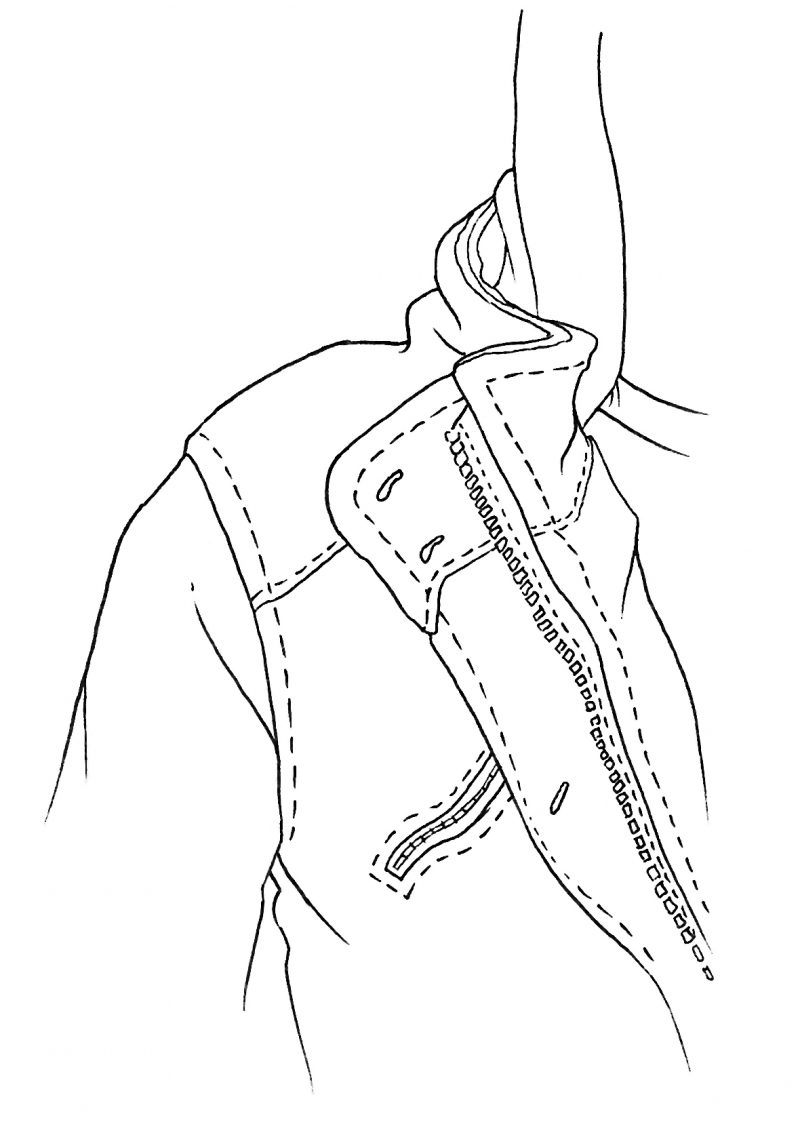

My fashion-connection Michael is part of a small but expanding conscious-clothing push. Freemans Sporting Club is an Americana-centric brand that feels like a mashup of Norman Rockwell and Jack London, with a meticulous aesthetic and an almost-mournful whimsy to its displays. The shopkeepers there can be a little stoned on handlebar-mustache wax, and will be on the phone saying things like “Justin’s on tour. I’m majorly bummed.” Its labels read, made local, buy local. Some items have a mile number on the tag, indicating how far away they were put together (some three miles, some four, some nine). Its “Casual Shirt” is $148, about six times what most of the country expects to pay for a dress shirt, and about two and a half times our $60 ethical buy-in. This is high-end specialty, the tip of a trend, more than a widely implementable model. Another example of a locavestite clothing brand is Grahame Fowler, a British designer who opened a store in the West Village. His looks are dandier (a suit modeled on a French railway worker’s uniform), but it’s all made in New York. There are places along the old clothing corridor of Orchard Street in Manhattan like Self Edge, for expensive, elite jeans (more Japanese than American), and Kai D., which specializes in stylized workwear, mostly made in New York. With certain labels, like Rag & Bone, you have to look closely: some garments were handsewn next door, and some were made in Asia. This is like how items in the grocery store require close reading—were these eggs laid in a genuinely humane farm, or are they free-range in name only? Does “natural” refer to how the animal lived, or how the meat was processed?

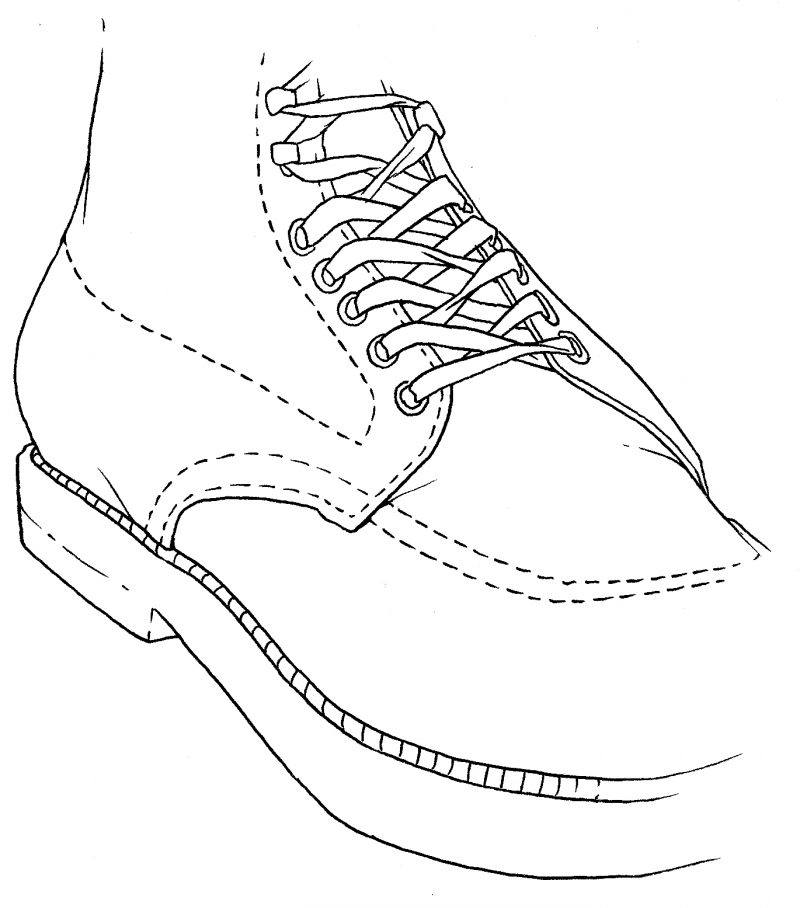

The movement has gotten me fantasizing about ($400+!) Alden wingtips (made, no, wrought in Massachusetts), though I feel like I’d need to get a law degree and good job to be worthy of them. Maybe if I somehow get the tenure I’m not even eligible for. The shoes are also being pushed by the ingeniously curated J. Crew Men’s Shop. It’s also an example of the co-branding/collaboration fad that is endemic to the “new-old” clothing movement. This partnering is a good way to build essence, and even though the collaboration concept feels owned by designers now, it started with big companies co-branding in “your grocer’s freezer,” when Oreos and Baileys Original Irish Cream started showing up in ice cream. “They’ll last at least ten years,” I’m told of the Alden shoes, and I start to picture myself in them. Yes: timeless man. You can sell a lot of men’s clothing this way: grow old in this sweater. There’s something comforting and sure about the notion.

However, women’s fashion, with its deeply rooted ideas about how femininity should be expressed, has different rules, and therefore a different angle on sustainability. Most women would not be excited to hear that a particular pair of shoes could be their main footwear for the next decade. It would be a sad prospect, representing being stuck rather than being stable. This mirrors how we think about male and female beauty. An older dude can be handsome like worn leather, so it would make sense that his shoes would be as well. Female physical beauty is generally not described positively in terms of old leather. Not that men don’t also get excited about renewal in the form of new clothes, but just compare the size of the men’s and women’s sections in any big department store. An example of a company that is working responsibly within fast-fashion ideals is the Brazil-based Melissa, which makes high-design plastic shoes in a factory that recycles almost all its waste, pays good wages, and melts down unsold models from the previous year to make next year’s. Their shoes sell from the $40 range to over $300, meaning the shoes still need more investment and love than some $10 throwaways.

Local-type clothing is trendy, sure, and “sustainable” is easy to make fun of (hard to write without wince-quotes). You can dismiss it all as marketing, and it’s also fun to marvel at the fact that we’ve managed to turn raising chickens into an act of bling, but aspects of this mindfully made clothing movement are valid and should persist—like taking into account who made something under what conditions, and buying things with an eye to using them for a long time. Habits change! That’s half the point of Mad Men. People aren’t going to stop wearing seat belts, or start bagging grass clippings again instead of turning them into mulch. I can’t believe this is all fad. If design schools are now teaching zero-waste, that will be part of a new generation’s way of thinking. I don’t think you can or should buy only made in usa; we’re not un-globaling, but supporting local industry is worth considering, for reasons beyond carbon footprints or mere patriotism. A varied and viable local economy is a good thing. If a lot of people in your community are unemployed because no one buys any local goods, you will end up paying for that. If you spend $70 on a shirt that a bunch of people in the area had a hand in making, then they have more money to spend on whatever it is you’re selling. Humanely treated workers and environmentally responsible factories should be standard, not a rare bonus. If you treasure your things, you’ll want less of them, and won’t throw them away or replace them so easily.

Fashion, of course, is always changing. We’ll get tired of “heritage” and “local” looks that seem to gaze only backward. We’ll crave the sleek, the cosmopolitan, and textures and colors that seem drawn from something other than nature. It’ll be exciting, but some of the enlightened values will stick. Maybe it’ll all be recyclable; the Melissa factory suggests a way.

So what might some clothing rules look like? This is just a test run, in the spirit of a textile Pollan:

*You can own well-made shoes and be a good person, contrary to what Michael Douglas characters would have you believe.

*For sneakers, imports are fine. They’re the experts. You should have no more pairs of sneakers than there are days of the week.

*Shoes should fit correctly in the store, and don’t try them on after walking around a lot, as your feet will have swelled up.

*If you go a year without wearing a pair of jeans, turn them into cutoffs or donate them. And don’t check too deeply on the politics of the organization to which you’re donating.

*America may have forgotten how to do a lot of things, but making good jeans is not one of them. Japan started later, but has caught up, and now produces what may be the best in the world. Spending more up front on jeans that will age gracefully should work out to a lower price-per-wear—especially if you can weather a few fit trends.

*Most stuff on the clearance rack is there for a reason—you don’t have to “rescue” it.

*Good service from someone who knows you and knows clothes is worth paying for—we were wrong to stray from this way of doing things.

*A nice-looking dress shirt for under $15 should be cause for anger and alarm rather than celebration, like with the 99¢ cheeseburger. Don’t buy it—the object or the ideology of low-price-over-all.

*It’s a bad sign if you find yourself feeling anger at prices that seem high. Instead of walking away, take some deep breaths and do some research. You might be paying for more than that “brand essence.” (Some things might just be overpriced, but not all expensive clothing is.)

*A good shirt should cost more than a good dinner.

*You don’t need the best of everything.

*Clothing beyond socks and underwear shouldn’t touch a shopping cart.

*Repairing something old can be as exhilarating (or at least as satisfying) as buying something new.

*Seek out brands that have some consciousness beyond style and price—be it organic cotton, good wages, a union shop, natural dyes, things like that.

*Think of clothing as an official “durable good,” meaning it should last at least three years.

*Just because you don’t ingest it, that doesn’t mean clothing doesn’t affect your health. Better clothing can lead to better posture.

We need rules because none of this happens naturally.

*

Growing up, I watched a lot of Family Feud, and one moment on the show sticks out, even became an inside joke. This was in the mid-’80s. One of the patriarchs, in his seventies, was at the front podium for the face-off. Richard Dawson presided. One hundred people surveyed, the top answers were on the board, here was the question: “Name something you buy that you expect to last ten years.” The old man slapped the buzzer. His answer was pure reflex, like if someone had asked him the opposite of cat. He belted out, “A pair of shoes!” A pair of shoes!

I think I fell off the couch laughing. Of course it wasn’t up there, and he got the big red X with the buzzer. You goof! A car! A house! A dog! A diamond ring! Who expects to wear their sneakers for ten years? Their leader had clearly lost his marbles. Didn’t he know that shoes came and went with the seasons? It wasn’t until now that I realized he was the sane one, and the big red X was on us.