I met Richard McCann a year ago at the Folger Theatre in Washington, D.C., where we had been relegated to the cheap seats at an awards show. A handsome man in a box-cut tux, he introduced himself and asked if I’d “had any work done.” I said not yet, but did he know anyone good. I wanted to tell him how much I loved his writing, how after reading Mother of Sorrows the mean sidewalks of Wheaton, Maryland, would never look the same. But there was too much other ground to cover: the best concealer, whether one needs to pay a lot for good moisturizer (no, one does not). There was more to say but the lights went down.

Why share our letters? You remember the story of the boy who while wandering the mountains finds a piece of iron that will give him immortality. His greedy family takes the rock and will not allow the peasants of their ailing village access. The vain sisters use the rock to make themselves more beautiful—but for whom? The young men of the village are dying of the fever. The father uses the rock to make him rich, but what is there to buy? The merchants have left the village to escape the fever. His mother uses the rock to become a great weaver and cook. But who can eat on a stomach ravaged by the fever? Disgusted by his family’s behavior, the boy takes the rock to the center of the village and drops it down the well, where it dissolves into the town’s drinking water. Did the rock cure the fever? We never find out. All we know is that the rock is for everyone.

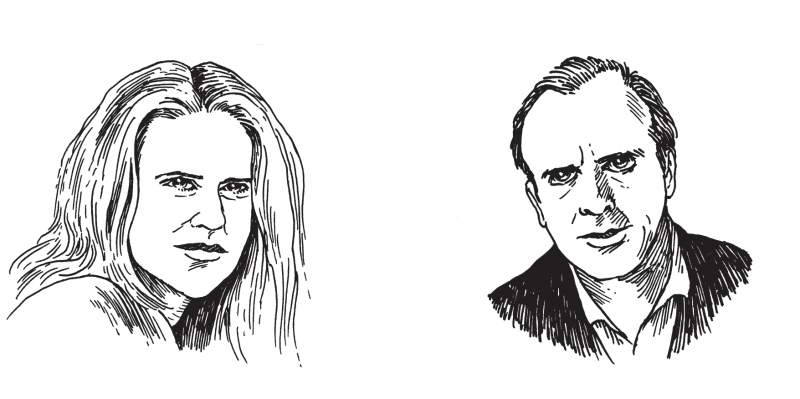

—Julia Slavin

Dear Richard,

I went to that flea market but the dollar was so weak against the Euro I couldn’t buy anything. I’d been hoping for an antique wooden Madonna, couldn’t even find an angel. And the prices! Some old dental tools, really frightening, especially a rusted steel impression of the mouth pried open, filled with real teeth, some missing: two thousand euros! A hard hat diving helmet: three thousand! Remember those Saturday afternoon movies that took place “under the sea” with a guy whose hose gets cut, runs out of air and can’t pry off the hard hat? There was always some frat boy in college with one of those diving helmets on top of his little refrigerator full of Schlitz. “C’est une chapeaux dans une condition excellent,” the owner of the stall told me, except for a small dent at the top where the owner had hit his head on the boat coming up for air too quickly when...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in