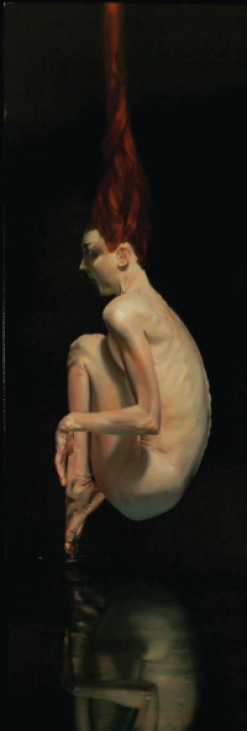

The painter David Abed recently held a show at the Century Guild in Chicago. Painstaking and figurative, the majority of the twelve oil-on-linen pieces are crepuscular depictions of inertia: solitary women floating in water, dead-eyed, dead-skinned, and radically alone. The mood of the paintings, individually and together, is isolated and estranged. In their otherworldliness they recall the mysterious imagery of the European symbolism of the late nineteenth century—appropriate, since the Century Guild is a gallery explicitly devoted to the symbolist movement.

In the symbolist tradition, Abed’s images are entirely personal, and thus ultimately inaccessible to the viewer. The colossal Between, for instance—a larger-than-life winged female nude, arms outstretched as if in languid crucifixion, walking across water in a way that might be Christlike were her eyes not so gleaming and ambiguous—has a specific narrative behind it, but we can’t access it just by looking. Abed painted it while his father was suffering from advanced throat cancer. Abed cared for his father by day and painted at night; at first the wings on the figure were closed, but as his father unexpectedly recovered, the composition changed: the wings began to open. Though the painting was essentially finished after a year, Abed continued to work on it as changes occurred to him: adding a red line to the horizon; making the eyes, which were previously human, green and glowing with light.

Unlike many contemporary artists working in relation to art history, Abed does not use pastiche or quote from symbolism. Though the works of some contemporary artists inspire the satisfaction of recognition—like John Currin, who applies Renaissance techniques to the flotsam of pop culture (Bea Arthur topless!), or Kehinde Wiley (Jacques-Louis David’s Napoleon Crossing the Alps—but Napoleon is black!), Abed’s work does not wink at or nod to history in order to interrogate contemporary attitudes. His is not a knowing symbolism, or an appropriation thereof. It just is.

So why does Abed embrace symbolism? A clue can be found in the show’s title, Liquid Modernity, a phrase that refers not only to the role of water in most of the paintings but also to a term coined by the Polish sociologist Zygmunt Bauman, who, seeking to replace the vague and overconnoted term postmodernity with something more useful, employs metaphors of solid and liquid to suggest that humans, individually and socially, used to be solid, rooted, and stable, but...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in