When published in other countries and before making its way here to the U.S., David Francis’s novel was called Agapanthus Tango. Here it is called The Great Inland Sea, which strikes me as more appropriate. The central problem with the title Agapanthus Tango is with the word “tango.” Though there is an important Argentinean character named Dickie, nothing in the book even begins to verge on the steamy sensuality of the tango.

To the contrary, David Francis’s book is hard and plain. The protagonist, Day, is a young 1940s Australian who watches his mother die on their bleak farm in the outback, and leaves for America with a horse. He falls in love with a young female jockey in Maryland. She is impenetrable and he suffers. They part ways. Day returns to Australia, to a father who has essentially forgone the act of communication altogether. Day learns things. Truths about his childhood are revealed to him. He suffers more as a consequence of that knowledge (consult Aeschylus).

Francis’s language confirms and complements the plot. Francis writes like a man who had to pay for the words first: “Dead horses are heavy, especially their heads.” Often he fails even to come up with a complete sentence: “Her curious, deliberate English.” He seems to think language really can get right up to reality as long as it does so quickly and in bursts.

But none of it has anything to do with the tango.

This is because The Great Inland Sea is fundamentally an Australian book. It is an attempt to come to terms with the bleak and terrible side of the Australian experience. For many of those who went to Australia as immigrants, the experience was one of privation and loss. The Great Inland Sea is about those harsh realities, but it is also about the validity of Australianness.

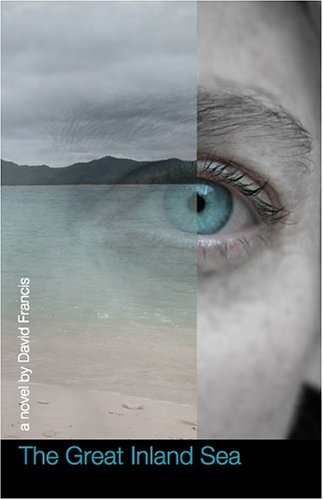

The most devastating comment a friend once made to me about Australia was that it is like America without all the culture. That is the onus under which every Australian, one supposes, must live. The Great Inland Sea accepts that onus and tries to redeem something from it. For a novel that forgoes the complicated literary devices of metaphor, symbol, allegory, and the like, the image of the great inland sea does most of the work. Witness the following dialogue from a scene in which Day is bringing Callie, his American girlfriend, to Australia:

“What’s Australia going to be like?” she asks.

“A big farm with flies.”

“Is it beautiful?”

“In a bleak sort of way. Heat and open spaces sound attractive, until that’s all that there is.”

“Are there waterfalls?” she asks. “A beach?”

“Not where we’re going,” I say. I don’t tell her the desert was once the floor of an ocean.

The guiding insight of the book, I think, is that there is something deep, something meaningful, about the process by which humanity is achieved even when so much has been stripped away. In the almost total failure of communication and culture that characterizes every relationship in The Great Inland Sea, one ends up, still, with the possibility of genuine human interaction. The last two sentences of the book (and I’m not ruining anything here, I promise) are “I have the words she’s drawn in the dirt. It’s more than I imagined.”

—Morgan Meis