When Audrey Munson was born—on June 8, 1891, to Katherine and Edgar Munson, in Rochester, New York—her life was expected to take the typical course of the life of a woman born in a rural area at that time. She was to grow up with strong morals, in a righteous family, receiving a cursory amount of education. When the time was right, she was to marry an eligible man and become the head of her own household, leading a simple life focused on the upkeep of family, hearth, and home. America was taking shape on the backs of women who followed these ideals.

But there was another option, perhaps best embodied in Theodore Dreiser’s 1900 novel Sister Carrie, in which Dreiser’s heroine lives a life of moral ambiguity as a rural woman who makes her way to the city, where she becomes a mistress and an actress. Like Carrie, Audrey was destined for a fate crueler and stranger than that prescribed for a woman of her era.

Audrey would later recount a legend that foretold her heartrending future. As a teenager attracted to the arts, she had spent her summers performing at the Rocky Point Amusement Park, in Rhode Island. It was perhaps there that she met a “gypsy” who told her, “When you think happiness is yours; its dead sea fruit shall turn to ashes in your mouth.” She further proclaimed that by her beauty Audrey would rise to the world’s heights, and that by her beauty she would be cast down.

The tale of the gypsy’s curse surfaced throughout Audrey’s life. She referred to it in interviews, where she was billed as “the exposition girl,” the artist’s model for the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, and, later, in tragic cover stories for Movie Weekly, when her career was on the wane. Perhaps it was a story she believed in, a fated tale that explained how a girl from nowhere had become the it-girl of the 1910s, “the Queen of the Artists’ Studios,” “Miss Manhattan,” “the most perfectly formed woman in the world,” a teenage model who found immortal success as the body that served as inspiration for the best artists and sculptors of the beaux arts era, who created work that catches one’s eye in New York City to this day.

It was a time of allegory, and New York City was constructing the buildings and sculptures that, by dint of their names and their representations of the naked female form, defined the ideals that the great metropolis was built upon: virtue, purity, plenty, civic fame. Eventually the city’s heights were crowned by Audrey’s face and body, cast in gilded copper, but by the time her likeness came to stand guard over all five boroughs, Audrey had left New York City and was living out the final sixty years of her life behind the walls of a mental institution, alone and forgotten. Her story is one of rotten luck and blinding talent, great highs and perilous lows, like Marilyn Monroe living through Jay Gatsby’s days of jazz and debauchery. She was a girl cursed with a body that brought her fame and work but that would eventually turn on her.

Audrey could look plain or radiant. When she smiled, her eyes were heavy-lidded and she had a toothy overbite. But when she posed, she had a face that could launch a thousand ships: a chin that curved like the wood on a violin, cheekbones that caught the light and revealed the perfect symmetry of a human face. Her breasts—teardrop-shaped, full, buoyant, the sort that would make men take up arms to defend American freedom—were accentuated by the long line of her body, and complemented equally by the curve of her buttocks. She was also gifted with two dimples of Venus pressed into her lower back, which proved to be “as valuable to [her] as Government Bonds,” as she once said in an interview.

Before her star turn, Audrey was just a teenage girl living in a tenement apartment in New York, practicing modeling techniques. If she wasn’t working, standing naked in an artist’s studio, shivering, sore, willing her body to remain in position, she was sitting on her bed, feet flat on the floor, a marble on the ground in front of her. Her exercises consisted of using her toes to grab the marble and clenching it tightly with her foot in a simian curve. Starting with her left side, she would bring her foot up to calf height, her muscles taut. She would grab the marble two hundred times on each side, for nearly an hour, as instructed by sculptor Karl Bitter, who told her that her feet would take on the shape of beauty with each movement. She would be able to see it happening, he said. Sitting on the bed, she looked at her calves and wasn’t sure.

When Audrey turned fifteen, her parents divorced. Her father was living in the small hamlet of Mexico in western New York, and her mother, Katherine, took Audrey with her on the second-class coach to New York City. Katherine got a job at a corset shop while Audrey enrolled in music school, dreaming of a future when she could pursue a life in the theater. While upper-crust writers satirized divorce as the ultimate upgrade by which an enterprising young woman could marry upward (like Edith Wharton in 1913’s The Custom of the Country), this path proved more difficult for Katherine.

One day, when Audrey was “standing in front of a department store window on Fifth Avenue in New York, wondering if, when I grew up to have money of my own, I could afford to buy some of the expensive hats I saw in the window,” fate stepped in. A photographer stopped Audrey and asked her if she would like to pose for him in his studio. “He explained that he had not meant to annoy me, but that he was a photographer and said my face was one he longed to photograph,” Audrey later recalled. His suggestion that she should bring her mother along was proof enough that his intentions were sincere.

The photographer, reportedly a man named Ralph Draper, showed Audrey’s photos to the sculptor Isidore Konti, who wanted her to come in for an interview.

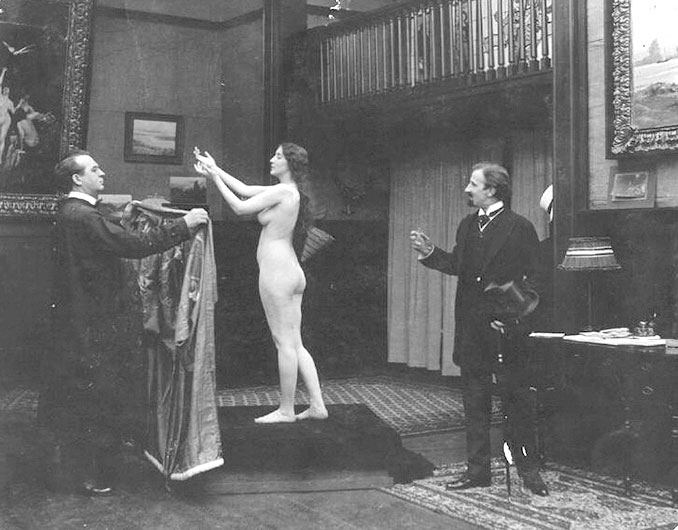

Though Konti didn’t see a need for the teenage model, he sat down and had tea with Audrey and Katherine anyway. Then inspiration hit: Konti asked Audrey to stand and walk for him. Struck by her form, Konti asked Audrey to pose nude. “He had an unfinished work on which he had been engaged for three years, but never completed because he had not found the proper model,” Audrey wrote. Her mother said yes, and they started sessions that led to the Three Graces sculpture, which hung in the lobby of the luxurious, now-demolished Hotel Astor for decades1. Audrey referred to the piece as “a souvenir of my mother’s consent.”

From her first sessions with Konti, Audrey was a quick study. With a letter in hand from the artist, she was able to introduce herself to other sculptors and painters and soon found steady work. Many of her employers had studios at 55 West Tenth Street, a Tin Pan Alley for New York’s beaux arts sculptors and artists.

At the age of sixteen, Audrey met with Adolph Weinman, who told her, as she recalled, “You are quite Grecian, yet you seem to have the warmth of motion the modern public likes to see in its models.” But he needed to see what she looked like nude, and he “brusquely” asked her to take off her clothes: “I want to see what nature did for you. Get your clothes off!” Audrey had her qualms, but she decided to “brazen it out,” undressing behind the curtain, and walked out and showed Weinman her form. “After all, I argued, I am just a model, just so many pounds of flesh and blood. He will not be scanning Audrey, the girl—but just a girl, the model.” Impressed with the girl’s “grace,” Weinman started on one of his signature works, Descending Night, which featured Audrey with her head bent and her hands in her hair, a goddess come down to earth.

Sculpture was the handmaiden of architecture in those days, and architects and artists trained at Paris’s École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in a classical style that had already shaped great cities like Rome, Paris, and Athens. They knew how to use the style’s techniques to take buildings to greater heights with beautiful lines, and they believed that the artist’s highest calling was to produce work for public spaces.

Money was pouring into New York from companies like Standard Oil and the transcontinental railroads, and the magnates that led these industries (John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, J. P. Morgan, and Charles Schwab) needed buildings to match their new wealth. There was a demand for European-style design that would convey New York City’s growing financial and political influence. At the turn of the century, there was a surfeit of skilled stone carvers in New York City who were immigrants from Italy. The classicism from the beaux arts school defined the new buildings, which required sculpture to match their heft and might: what else could represent the apex of humanity better than a nude female form? The right artist’s model suddenly had an abundance of jobs at her beautifully arched feet.

One of those who benefitted from New York’s new riches was the architect Stanford White. His buildings defined New York City architecture in the beginning of the 1900s, though his influence was cut short in his prime when he was murdered at the hands of Harry Thaw, in 1906. (Thaw was defending the “honor” of his wife, Evelyn Nesbit, an “it-girl” actress and model.) The case drew the eyes of the “sob sisters” of yellow journalism, female reporters who wrote both women-friendly lifestyle stories and lurid true tales as the newspaper business exploded. As one of the first American scandals, the White murder may have put Thaw on trial, but it was Nesbit who became a tabloid star. She was one of the first femmes fatales, and her sexuality and work as an actress, dancer, and model were put through the wringer; in retrospect, she would end up serving as a warning to Audrey about just how easily a reputation can be soiled in the light of scandal.

But during this time Audrey was overwhelmed with work. She modeled for the greatest sculptors and painters in New York, including Alexander Stirling Calder, Daniel Chester French, and Karl Bitter. She made thirty-five dollars a week and lived simply, in a small one-bedroom apartment that she shared with her mother. The art that she posed for, however, was a gateway into the upper echelon of society. When Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands commissioned Bitter to create a Venus de Milo statue “with arms,” Audrey’s arms served as the inspiration. The Rockefellers had an Audrey. She modeled for Adolph Weinman’s Civic Fame, a twenty-five-foot-tall copper and iron statue that was placed on top of the Manhattan Municipal Building, symbolizing the five boroughs’ unity and serving as the third largest statue in the city, greeting weary visitors as it sparkled in the sky. But the artist’s model remains “ever anonymous,” as Audrey wrote in the New York American. “She is the tool with which the artist works, and none may do her obeisance, though she provides the inspiration for a masterpiece and is the direct cause of enriching the painter or sculptor.” The best a model could hope for was a recommendation to another artist, another job, and the pleasures of work.

As Audrey modeled, she gained fame as an authority on feminine beauty and deportment. An article called her “the Queen of the artists’ studios,” and a 1913 New York Sun feature named her “Miss Manhattan” after she posed for sculptures that would end up on the Manhattan Bridge. She had stories and advice for the women’s pages on how to be beautiful: “Clothes ruined us. They do harm to our bodies and worse to our souls. So few young women of today know what to do with their hands, how to carry them and how to use them in company because their clothes are in the way.” While the “New Woman,” as Henry James termed it, was finding respectable employment in the bustling metropolis during the era when the suffragette struggle was taking flight, Audrey was, despite her “entertainer” status as an art model, preaching something like freedom for women in her radical attitude toward clothing.

In an interview, Audrey said, “No woman who is conscious of clothing is truly feminine or truly beautiful.” The pursuit of beauty, for Audrey, required study and practice, thinking lovely thoughts, “eschew[ing] all athletic exercises,” and avoiding makeup. She freely gave advice regarding the pursuit of beauty, with the greatest gems coming from her autobiographical column from 1921, “The Queen of the Artists’ Studios,” for the New York American. There she wrote: “The greatest of foes to feminine beauty are the kinds of garters most women wear—the garter that holds up their stocking from the corset or from a belt at the waist.”

Nineteen thirteen was a seminal year for art in New York, and across America. The beaux arts sculptors and painters worked on the pieces that would become beloved for their public representations of mankind and popular allegories. But there was something wilder on the horizon, and it was embodied in the 1913 Armory Show. Often referred to as the birthplace of modern art, that year’s show caused a stir by showcasing new European art forms, including cubism and fauvism, in which the human body was rendered in sharp and crude lines. Sculptors like the neoclassically trained Daniel Chester French were now considered too passé for the show, not daring enough. Though Audrey was was still enjoying consistent work and success during this time, the show posed the question: in a world where the silent scream of Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase nearly caused riots, was there still a need for an art model with a Grecian look? For the time being, at least, the answer was yes. But Audrey’s elegant planes and soft curves were in stark opposition to Duchamp’s nude, who was rendered in browns and ochers, lines and cone shapes that, taken together, seemed to connote sexuality, and heralded a new approach to women’s bodies in art. “In America, as in France, Cubism, Futurism, Impressionism, and other art-isms have become quite a fad. Of course I think these ‘new’ artists are just crazy persons capitalizing their insanities,” Audrey wrote in 1921, with the gift of hindsight, after these –isms had put her out of a job. She also told a story about a cubist impressionist who said to her that Konti’s Mother and Child, which featured Audrey, was all wrong, because “who thinks of a mother and a child without at once visioning in his mind the father of the child?” This artist felt that the mind’s eye was so busy imagining a father to add on to the classical mother-and-young-child tableau that the image needed to be impressionistic and blurry.

But before cubism took over the American art world, there was the Panama-Pacific International Exhibition of 1915, where Audrey would receive her greatest honor as a model. The exhibition was held at that year’s World’s Fair, which served as a celebration of both the opening of the Panama Canal and San Francisco’s rebirth after the 1906 earthquake. Named the official “exposition girl” by Karl Bitter and Alexander Stirling Calder, who were the acting chiefs of the fair’s sculpture program, Audrey was the model for many of the more than fifteen hundred sculptures shown there. When fairgoers walked into the pavilion, they were greeted with a chorus of marble Audreys. Imagine stepping into the promise of a new world, the best of all possible worlds, onto a grand concourse lined with numerous statues of the same serene woman, her eyes following you as you walked down the parkway.

The San Francisco Chronicle wrote an article on Audrey, describing her as “the most perfectly formed woman who ever posed in an American studio.” The paper noted that “you would not pick her out as a show-stopping beauty,” but that “she can make a pot of tea or toast bread over an open fire without the least show of importance.” In the article, Audrey gave advice for aspiring art models. “If [she] wants to keep the place she had won, she must be businesslike.” She stressed that holding a pose is not as easy as it sounds: “One must not only study the person for whom she works, but she must study his work and the character of the pose he would like.” She said girls who want good figures must lead a regular life, eat right, exercise, get good sleep, and get regular massages. “This my mother has done for me all my life,” Audrey said. “I have found that the artists say that their best models have always [led] simple lives and abandoned the corset.”

In celebration of her role at the fair, Audrey was featured on the cover of Sunset magazine, then one of the premiere magazines of the American West. Eighteen million people visited the fair and fell for her immortal curves. Art critics were in love. She was called “Miss Panama,” and Daniel Chester French was quoted in the New York Herald, noting Audrey’s versatility in appearing in both powerful and rugged sculptures and comparing her to his own work—including his delicate, radiant Genius of Creation.

Not everyone was a fan of the “exhibition girl,” however. “This young woman should be ashamed of herself,” Elizabeth Gannis, founder and president of the National Christian League for the Promotion of Purity, told the San Francisco Chronicle. “Maybe she has perfection, as the sculptors call it, of features and figure. That doesn’t give her license to parade her charms to the general public.”

The censors had their hackles up, and Audrey was on their radar. It was the perfect time for Audrey to segue into another career: she would become a silent-film actress.

Hollywood operated like the Wild West during the silent-film era. Before the studio system took flight, anyone could create a film shingle in order to make pictures to take on the vaudeville circuit. Audrey appeared in Inspiration, Purity, and The Girl o’ Dreams in short succession, between 1915 and 1918. All three films featured Audrey as an “artist’s model” of some sort, and promised that viewers could see “the Famous Model for America’s most celebrated paintings and statuary in a powerful masterpiece.” She was the first woman to appear naked on film in a non-pornographic capacity, a fact that would be touted in both the publicity and the controversy around her films. The nudity was for art’s sake, but the National Board of Review demanded cuts in the films so that Audrey’s naked body was less shocking: seen only at a distance, posed in stillness, or glimpsed momentarily. Inspiration was advertised as morally depraved, and it was a box-office hit, making millions.

Out of her four film works—she would go on to make another, Heedless Moths, in 1921—only Purity exists today, in a compromised print. Written by Clifford Howard, Purity was an allegory, with Audrey playing two characters—“Virtue” and “Purity”—inspired by her life. Purity was the muse and the lover of a poet who falls ill and needs money to publish his book. When Purity is caught changing and bathing in a stream, an artist watches her from afar, and he asks her to pose for him. She does it in secret, for the money, so that the poet can print his gorgeous verse, but her modeling leads to working at a party where she has to fend off another man’s amorous advances. When the poet meets the artist, he finds out the truth: that Purity has posed for this man. Purity is dumped, but she tells him that she modeled for his sake, to make his life better. She wanted him to publish his poetry so that the world could read it. She asks forgiveness. The film ends with the poet and Purity reunited.

The New York Times said that Audrey Munson’s figure was “systematically and thoroughly exploited” in the film, which played at New York’s Liberty Theater, after it had the proper deletions from the Motion Picture Commission, which could stop a film from being exhibited if it was not up to par. Morally, Purity was up to par, but whether it was up to par artistically was another question: the Times’ review concluded that after Purity and the poet reunite, “from the sample of his verse flashed on screen you fear the end did not justify the means.” In a 1928 interview with Howard published in Close Up magazine, the writer recalled, “Sermons were preached about it, pro and con. The old maids of both sexes who sneaked in to see it were becomingly shocked, while stout-moraled men and women openly extolled it.”

All four films were made for the American Film Company and the Thanhouser Company, earning millions of dollars. Both companies made sure that Audrey was able to tour the United States by train, a vast extravagance at the time, to present and show her films. In 1916, during the tour, she was arrested for “indecency on stage” in St. Louis. She had thoroughly embraced acting, however, listing her residence in Santa Monica and her occupation as “photoplayer.”

Whether Audrey could transition to acting remained a question. Her films hired a lookalike stand-in, Jane Thomas, to perform, while Audrey stuck to posing nude. But she had already been a model for years, and it was a ride that could be over at any minute. Acting was a possible option beyond modeling—if she ever exhibited a talent for it.

She was the most famous art model in America, and now she was making a name for herself as a performer. Audrey, with her generous and open attitude toward nudity, became a lightning rod for controversy, with both admiring and judgmental audiences attending her shows. But everything changed on February 27, 1919. A noted New York physician, Dr. William K. Wilkins, and his wife, Julia, were returning home to their summer house on Long Island, and came upon robbers. Julia’s skull was bashed in by a hammer: seventeen blows to the head. She was found dead in the driveway. The Wilkins murder immediately grabbed the headlines when it became clear that the “robbers” weren’t the main suspect at all: it was Dr. Wilkins himself. When a warrant was issued for his arrest, the doctor went missing.

Audrey’s link to the murder was tenuous at best, a jump of logic based on the fact that she and her mother were tenants of the Wilkins’ building in New York City. The police announced in the papers (including the New York Times and the local tabloids) that they were looking for her for questioning. Audrey was out of town, however, performing in Canada. Media frenzy was already in full swing, and journalists were writing exquisitely purple prose regarding the Wilkins murder in articles that speculated that the key might be held by “the most perfect woman.”

While they waited to find the perfect woman herself, the May 18, 1919, Sunday Morning Star painted a vivid picture of the scene: “The parrot in its cage, looked out at that murder. The monkey saw it, and the dogs, too. But parrots and monkeys and dogs cannot talk nor testify in court.” Where is Audrey? they wondered. Why wouldn’t she testify? “A mystery of the case is why Miss Audrey Munson and her mother left the Wilkins home at 164 West Sixty-fifth Street a few days before the murder… She declines to talk.” The paper goes on to ask, “Beautiful Audrey Munson, actress, famous as the most perfectly formed woman in the world—what does she know about the mysterious murder of Mrs. Wilkins in the queer old house by the sea?”

Once the belle of the art world, an actress on the rise, Audrey was suddenly a wanted woman on the run, the femme fatale in a brutal crime of passion. The authorities began a nationwide hunt for Audrey, who had last been seen performing in a vaudeville production in Toronto. It was reported that “the Burns Detective Agency has located Miss Munson in Canada, but has not been able to serve her with a subpoena or induce her to appear as a witness.”

The tabloids had ample room to speculate, and they gleefully bit into this story: in their hands, the oft-nude Audrey was a jezebel and a temptress, flirting and leading on her elderly landlord so that his only option was to murder his wife so that he could marry Audrey. Newspapers ran advertisements for Audrey’s new film that capitalized on the scandal. Ads asked, “Where’s Audrey? Find the girl everyone’s looking for in Girl o’ Dreams!”

A month later, Audrey’s reputation was in tatters. Audrey and her mother eventually testified to the police that they had left the apartment several days before the incident, after the doctor had annoyed Audrey by saying, “Don’t ever get married. If you do you will lose your symmetrical figure.” Doctor Wilkins was convicted of the murder and sentenced to the electric chair, but before the sentence was carried out, he committed suicide, in jail, in the summer of 1919.

How had Audrey’s bright career ended in the span of a month? Was it simply the scandal of the Wilkins case? Or was there something else driving her failure? In a maudlin cover story from Movie Weekly in July 1922, “The Awesome Tragedy of Audrey Munson’s Strange Life,” Audrey attributed her downfall to an incident that occurred around the time that the Wilkins murder took over the tabloids. According to Audrey, she had been acting in a vaudeville production called The Fashion Show. When she refused the advances of a prominent man in the theater world, the show closed immediately, with no explanation. She described the assault in vicious terms:

He passed his arm around me and pressed his burning lips against my shoulder. I struggled to free myself. I struck at him. “Get away from me!” I cried out. “Don’t touch me. I hate you. Your touch is repulsive to me. I would rather have a snake crawl over me than to feel your hand upon me”… “You will have cause to remember this,” he said—and left me. A few days later I was told the “Fashion Show” was to close. I had no explanation.

Whatever the reason, it was too late for Audrey to make a comeback. Her film contract with the American Film Company was terminated. Her work as a model dried up. She was no longer in demand. It was wartime, and many American artists were in France. Those who remained had moved on to the new style of abstract modernism, influenced by cubism and fauvism, and away from realistic sculptures. Besides, the world already knew her body and her repertoire of poses. She had tried every possible option to get work and earn money. The world had moved beyond her skills as a model—and she was aging as well.

Audrey’s film career never got the chance to really take off. Her fame as “the most perfectly formed woman in the world” stuck to her and now likely hurt her. In a 1920 interview with Daily Variety, Audrey said that the Wilkins case “ruined her career.” She made the rounds of studios in “vain hope,” she said. “After I tried to find something to do in Toronto, New York City, Kansas City, Chicago, and Detroit, I came home. I was brought up in Syracuse and thought I could get rid of this horrible bugbear of suspicion here… the public seems to have grown to hate me. And I cannot help thinking that the feeling was fostered in some powerful quarters.”

Audrey did not have savings. The thirty-five dollars a week she had received for modeling and the twenty-five-hundred-dollar fee for her films didn’t last long. Her films had pulled in millions, and Audrey sued the studios for failed payment of salary, but she didn’t win. Out of money and out of options, Audrey and her mother moved back to the tiny western New York town of Mexico, where they lived in one small room. While Katherine sold kitchen utensils door-to-door to make money, Audrey had difficulty finding employment.

This was the point where Audrey’s life got even more bizarre. To revive her career, she—or a ghostwriter, although the voice sounds like Audrey’s does in interviews—began a series of columns for the New York American, telling salacious tales of what really went on behind the scenes in art studios.

The voice was the most striking thing about Audrey’s column: raw and personal, it related anecdotes that served as links to other American tragedies about the pursuit of art in a hostile world. The column gave Audrey a chance to clear her name and reputation, and she made sure to paint herself as a conscientious and hardworking model, one who was aware of the temptations in her chosen field but who lived a virtuous and cloistered life: a role model for young women.

It was a rebranding effort—maybe the first of its kind—that remains interesting today. While today Tyra Banks tells the “secrets” of modeling on each episode of America’s Next Top Model, in 1921 Audrey did the same in her syndicated nationwide column. She shared her beauty secrets. She told the world how hard she worked to be a great model, standing still even when freezing water was dropped onto her head, studying the great artists, doing her exercises.

The columns are also juicy, filled with vivid writing about the temptations of money and sex that came along with work in the art studios. One column concerns a friend named Elsie, whom she had helped to find work as an art model, and who started to work later and later into the night. Eventually Elsie fell into “bohemia,” a culture of dilettante artists and models who “go into posing because it is easy work, they think, and who consequently are on the look out for and are easily persuaded into pastimes.” Too much partying meant that Elsie disappointed the true artists, who asked: “How can a woman be a bacchante at night and an angel at ten in the morning?” Audrey’s response was simple: “She can not be.”

Audrey also gave interviews announcing that her comeback was imminent. An article ran in the St. Petersburg Independent in January 1921, stating that “Audrey Munson has known poverty, trouble, but is coming back again.” It discussed how, penniless, Audrey and her mother had moved back to her childhood home in Syracuse. “With her mother she went to Syracuse merchants and begged work as a clerk; to restaurants where she sought a job as a waitress… None would hire her.” It told of how Audrey and her mother lived in one furnished room, “cooking their meager meals on a tiny gas plate attached to a jet.” But happier times would be coming: there was a new film opportunity on the horizon, the result of an influential friend who interceded with a film contract. “I’m only 27—think of it!—and I have time to build a new career. We’ll succeed too, won’t we, mother?” Audrey asked in the piece. Her mother, described as Audrey’s one true friend through trial and trouble, smiled and said, “We’ll try real hard!” But the article wondered: will public opinion let her? It is hard not to see shades of future fallen stars and former it-girls in these words.

In June of 1921, Audrey’s last film, Heedless Moths—“the big, fine, clean photodrama with the punch,” according to the poster—opened in New York City. It was Audrey’s opportunity to change the public’s view of her talents. Filmed before the Wilkins scandal had ruined her career, the film pinned her future on whether or not the public responded to what was billed as the first “great” picture featuring Audrey. It told the story of a model who both inspired an artist and saved his marriage with her moral values. It was based on a scenario true to Audrey’s life—at least, as she presented it in her column.

Promotion for the film billed it as “the unknown history of the inspiration of many masterpieces in public and private collections, the strange eccentricities and methods of the artists, and the distressing tragedies of the pretty models who lacked the moral balance to safeguard them from the perils of the intimate atmosphere of the studios.” It was also the film in which Audrey’s lookalike stand-in, June Thomas, who was tasked with the “acting,” was busiest.

Audrey still had a knack for scandal. A New York Times piece from June 1921,“‘Descending Night’ Sets Village Agape,” reported, “The attack on the morals of Greenwich Village centred last night about the fair form of Audrey Munson, as pictured on a poster reproduction of the statue for which she posed. ‘Descending Night’ has none of the intriguing and shadowy vagueness which marks the equally well-known ‘Nude Descending the Staircase.’ There is nothing cubist or futurist about this poster.” The New York Times review called Heedless Moths “dull, dull, and incredibly mechanical,” sighing over the fact that it had to be a moral tale, even though the pitch held some intrigue. Heedless Moths was the film where the Audrey/Jane Thomas split was the most obvious, and once it left theaters, Audrey’s career in films was finished. It was not the comeback vehicle that she had banked on.

So what was a girl to do? Audrey had one last chance to find what she wanted as an artist: success, press, attention, love. She placed an ad in the local newspapers looking for a husband. She would marry, she wrote, if she could find a husband “as physically beautiful” as herself. Hundreds of men responded to the ad, and Audrey announced, after a year, a whirlwind engagement to a rich and handsome suitor, a wartime fighter pilot whom nobody had heard of, Joseph J. Stevenson of Ann Arbor, Michigan. Despite the glamor of this announcement, Audrey was still living close to the bone in Mexico, New York, with her mother working as a housekeeper.

Audrey’s romance ended under mysterious circumstances. On May 27, 1922, Audrey allegedly received a telegram from Ann Arbor, and, according to the papers, then attempted suicide by drinking bichloride of mercury. A story line pushed by the press was that the telegram had been from Audrey’s suitor, the mysterious man from the Midwest, who had called off the wedding. The New York Times reported on the suicide attempt. The first article said, “Audrey Munson Takes Dose of Poison”; the follow-up screamed: “Audrey Munson Is Out of Danger; Penitent, Wants to Live.” The Times later ran an addendum, reporting on the search for Stevenson in Ann Arbor, and saying that they “had failed to reveal any trace of him. So far as can be learned, no man by that name ever lived here.”

At thirty years old, Audrey was known throughout the town of Mexico as “the woman who took her clothes off for money.” Mothers would shut their blinds if they saw her coming down the street. After the few articles about her hopes for a comeback and her struggles with poverty, the media lost interest in her travails. She lived quietly with her mother and six dogs. They moved from house to house, at one point spending time on a farm where Katherine was employed as a housekeeper. Audrey had always been nervous, and now she was depressed and, allegedly, abusing drugs. Her behavior had become more erratic. There were reports that Audrey had been seen roller-skating or mowing the lawn; as Andrea Geyer reports in her book Queen of the Artists’ Studios, locals told her that Audrey was often seen wearing a bright, colorful scarf tied around her head, a precursor of sorts to Little Edie Beale of Grey Gardens.

In 1931, Audrey’s life took another dramatic turn. One news story said she had been fingered as the probable arsonist in series of barn fires and had had to face a local judge for the final verdict. Another said that she had become too difficult to handle—a grown woman dealing with emotional problems—and that her mother had brought her to a local judge. Audrey was sentenced to reside at the St. Lawrence State Hospital in Ogdensburg, New York, before her fortieth birthday.

At the time, hospitals for the mentally ill weren’t simply for those who were clinically insane. They were also places for people whose families couldn’t take care of them. Audrey’s institutionalization may have been due to mental-health issues, or to the fact that her ever-loyal mother was aging and could no longer care for her. Whatever the reason, she would live out the rest of her life in Ogdensburg.

Many artists who achieve the level of success that Audrey did in her teens and twenties don’t live to experience the long fall back to earth that she endured. Audrey’s curse may have been that she persisted even as her fortunes faded, losing everything when she was rejected from the industry that had borne her to such great heights and sustained her life there. Audrey outlived her time as a muse. To go from being validated for her body, her beauty, her studiousness, to being a pariah and “the woman who took her clothes off for money” must have been a source of great suffering—perhaps the sort of suffering that could find its balm in an asylum.

Audrey’s new home was its own community, spread out over one thousand acres at Point Airy in a design, as Andrea Ray noted in her report on the asylum, that was reminiscent of that era’s great Adirondack camps and the communities of the utopian society movement, which had its roots in western New York. The asylum was split into a series of buildings, including a farm, a theater, a beauty parlor, and a bowling alley. The patients were encouraged to take up hobbies like farming, sewing, or weaving, and they could participate in dances, teas, and theater. Most patients, like Audrey, had been involuntarily committed.

Today Audrey’s remains lie in an unmarked grave, and she will be remembered primarily as the first woman to appear nude on film. But despite the ignominy of Audrey’s death, she left a legacy behind in the countless pieces of sculpture inspired by the planes of her immortal face and body. “I marvel at the tricks of the fate that shapes the after-life of the world’s most popular artist’s models,” Audrey wrote in “Queen of the Artists’ Studios.” Perhaps Audrey sensed her fate. Maybe the gypsy’s curse told her what she already knew: that “a woman’s beauty has been dangerous since the time of the first successor of Eve,” and that it is the rare model, according to Audrey, who escapes the lifestyle with her soul intact.

A walk through New York City today is a walk haunted by Audrey’s visage: there she is gazing out from the Manhattan Bridge like the figurehead on a ship, flanking the entrance to the Brooklyn Museum of Art, in a constellation of statuary at the Metropolitan Museum of Art; hers is a familiar face, with its cheekbones, and dimples, in the facades and statues of Central Park. Her perfectly arched feet anchor a statue in Saratoga Spa State Park. Her face gazes out from the friezes of the Frick Building and the Forty-Second Street library. Going down Riverside Drive is a walk past statues bearing Audrey’s face and body, a sturdy memorial to the heroes that shaped this city, the artist’s model enduring, phoenix-like. Yet her crowning glory remains Adolph Weinman’s Civic Fame, atop the Manhattan Municipal Building. It can be hard to remember that a teenage girl served as its inspiration—offering her body for a chance at immortality, showing the price that some people have to pay just for a chance to scale the heights.

The author is grateful for the work of Diane Rozas and Anita Bourne Gottehrer, whose book American Venus: The Extraordinary Life of Audrey Munson, Model and Muse was an invaluable resource, as well as for the work of Andrea Geyer in her Queen of the Artists’ Studios: The Story of Audrey Munson.

1. The sculpture’s current whereabouts are unknown.