“Oh great brotherhood of Jules Verne, Paul Klee, Sandy Calder, Leonardo da Vinci, Rube Goldberg, Marcel Duchamp, Piranesi, Man Ray, Picabia, Filippo Morghen, are you with it?”

—Alfred H. Barr Jr., from a broadside distributed at Homage to New York, Museum of Modern Art, March 17, 1960

A Fire in the Piano

On a frigid Manhattan evening last February, Chelsea’s Alexander and Bonin gallery welcomed a small crowd for the opening of British artist Michael Landy’s enigmatic show H2NY. Those familiar with Landy from his notorious February 2001 installation, Break Down, which enjoyed heavy international coverage, surely arrived expecting a grand spectacle. Over the course of fourteen days, Landy systematically destroyed all 7,227 of his personal possessions in a vacant department store in London’s Oxford Street shopping district. With the help of twelve operatives dressed in matching blue overalls, the cataloging of the items and their subsequent destruction in a grinding machine evolved as an inexorable performance. Forty-five thousand visitors inspected the site of the destruction, many of them stunned shoppers who happened upon the department store window to witness what Landy has called an “island surrounded by the everyday world we know.” Among the items destroyed: all of Landy’s clothing, his Saab 900, and a valuable art collection including works by celebrated British artists Tracey Emin and Damien Hirst. Landy admits that he had originally considered recycling or giving away the items but later decided that their destruction was essential to the meaning of Break Down. (Emin, critical of the endeavor, visited Landy during the performance to ask for the return of an embroidered handkerchief she had given him. The handkerchief had already been pulverized and Emin was given only its granulated remains.)

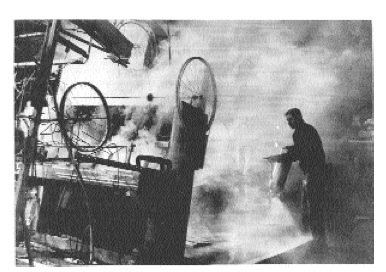

In an interview in the Independent, Landy claimed that Break Down was about “society’s romance with consumerism.” H2NY added another layer to Landy’s ostensible romance with destruction even as it appeared, to those entering the Alexander and Bonin gallery on that February night, like a run-of-the-mill gallery showing of twenty or so framed drawings of fires and machines. While the 2007 “break down” at Alexander and Bonin was less dramatic and overt, H2NY took as its inspiration a March 17, 1960, sculpture-based “machine suicide” orchestrated by Swiss-born French kinetic sculptor Jean Tinguely called Homage to New York. The show’s catalog revealed that the titles of Landy’s drawings were variants of the newspaper headlines that appeared in conjunction with Tinguely’s machine: H2NY tinguely’s contraption, Nation; H2NY gadget to end all gadgets, burns out, New York Journal; and H2NY the tinguely machine, the Village...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in