Fletcher Hanks, nicknamed “Christy” after Baseball Hall of Famer Christy Mathewson, was, by all accounts, a louse. An alcoholic and a wife-beater, Hanks once kicked his four-year-old son, Fletcher Jr., down a flight of stairs. The punt and subsequent tumble left the boy unable to speak intelligibly for five years. “My old man didn’t like runts,” explained the younger Fletcher. The boy was runty, to be sure, and suffered from rickets, but his dad’s rage was something beyond reckoning. “My father,” he said, “was the most no-good drunken bum you can find.”

When Hanks wasn’t pummeling his wife or abusing his young son, he wrote and drew superhero comic-book stories. Hanks completed a few dozen of them between 1939 and 1941, the dawn of what is now considered the genre’s golden age. There are few remaining copies because the characters didn’t catch on with readers, and Hanks, as an artist, didn’t catch on with collectors. Among his creations were Stardust, an interplanetary crime fighter, and Fantomah, a white jungle-protectress.

This month, Fantagraphics publishes I Shall Destroy All the Civilized Planets! The Comics of Fletcher Hanks. Edited by cartoonist Paul Karasik, who discovered the artist in the early ’80s while he was an associate editor at Art Spiegelman’s comics review Raw, the fifteen-story collection boasts visual wonders freakish and rare. There are a rabid mandrill and a furry Venusian, asphyxiated magazine editors and giant bipedal rats. Bombings, gassings, and islands turned waterside down are all part of the Hanks landscape. Most peculiar of all, however, is that, contrary to every rule of the genre, the stories are almost completely devoid of fights.

Most traditional superhero comics follow a predictable format: The villain does something villainous. Hero and villain fight. The villain is captured, or beaten into submission, or is accidentally killed. Within this tripartite structure, the pre-conflict setup and post-conflict comeuppance serve largely as bookends to the fight scenes, which make up the narrative meat. In the tales of Fletcher Hanks, however, there are hardly any fights at all—few, certainly, of any consequence or duration. Instead, there are extended setups during which the villain commits a variety of horrific acts. After a speedy capture (often without a blow thrown) the reader is treated to panel after panel of the villain being tortured, humiliated, and tossed about.

Here is one story: Stardust, “the most remarkable man who ever lived,” discovers a plot to steal all the gold from Fort Knox. The evil Slant-Eye (despite his title, he is not of Asian descent) plans to use the gold to establish a “modern pirate stronghold” on a South Seas island. He and his henchmen drop gas bombs on the fort, then beat many of the guards to death. Before the gangsters can steal the loot, Stardust incapacitates them with a “mysterious ray.” Stardust makes his hand grow to the size of a large skillet, grabs Slant-Eye, then flies with him high above the villain’s island. He uses his powerful “agitator ray” to create a tidal wave, which swamps the island. Stardust drops Slant-Eye into an inland whirlpool, which sucks the villain down into a tropical cave. “Help! Help!!” cries Slant-Eye. A “shining octopus of gold” grabs the villain in his tentacles. “Ow-w,” yelps Slant-Eye. “This is your fate,” says Stardust. “You craved gold, so here it is.” The golden octopus pulls Slant-Eye, formerly crying and yelping, now “speechless with dread,” down into his underwater lair, where, presumably, he is devoured.

Other stories exhibit the same fight-free narratives and moral symmetry. In one, a man leads an army of gigantic spiders into a jungle village, where they feast on panic-stricken natives “by the thousand”; in the end, the villain is eaten by one of his own spiders. In another, a wealthy pilot looses fifty thousand gigantic panthers onto the streets of New York; later, he is eaten by the fearsome felines. The didactic harmony between sin and punishment reminds one of Struwwelpeter, Heinrich Hoffmann’s nineteenth-century collection of children’s stories. In Hoffmann’s book, a disobedient girl plays with matches and is burned to a crisp, a boy refuses to eat his soup and dies of malnutrition, a thumb-sucker’s thumbs are clipped off with giant scissors. And so it goes.

At first blush, many of Hanks’s stories look and sound like classic examples of poetic justice, but are they? Hanks seems to think so, as do the cartoon heroes who do his bidding. “You tried to destroy the heads of a great nation,” Stardust tells the evil De Structo, “so your own head shall be destroyed.” Upon closer examination, however, the justice doesn’t seem so poetical, if for no other reason than that it all feels so forced. The spiders don’t, for example, feast on the villain of their own accord; he is delivered over to the spiders by the jungle heroine Fantomah. De Structo’s head doesn’t explode on its own because it’s been packed too full of evilness; rather, Stardust flings it into the greedy waiting hands of the Giant Headhunter. That’s not really poetic justice—that’s vengeance, done with an eye to the poetic. It would be as if the younger Fletcher, now grown, had returned to his family home and pushed his old man down a flight of stairs. Understandable, yes; appropriate, maybe; poetic justice—not so much.

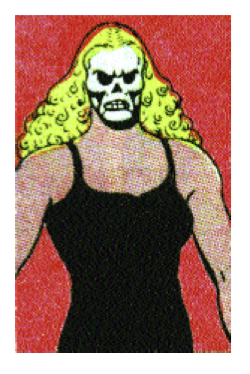

What it most resembles is divine justice, but, if so, what weirdos these gods be! Fantomah is a Garboesque beauty whose head becomes a ghastly bluish skull when she becomes angry. Stardust, a.k.a. “the most remarkable man that ever lived,” delights in transforming his beaten foes into rats, or midgets, or simply flinging them into space. If these are gods, they’re deities of the Old Testament variety, which doesn’t make for the most sympathetic or nuanced of characters. Milton’s God was like this, which was why, in Paradise Lost, everyone ended up rooting for Satan.

What’s missing is some sense of motivation (say, a god’s love for its people), but neither Stardust nor Fantomah seems to have any people, let alone any friends to speak of. They protect generic humanity, or, in Fantomah’s case, the inhabitants of some unnamed jungle. Righteous rage might spice things up here—something along the lines of Sodom and Gomorrah, or Bruce Lee beating on the Japanese in Fist of Fury—but both heroes dispatch their foes with a kind of smug detachment, or the sternness of a parent scolding a three-year-old. If Stardust and Fantomah are having fun hanging their foes from the tops of trees or turning them into icicles, we certainly don’t see it in their faces.

Which is a fortunate thing, since Hanks wasn’t much for such art-school frou-frou as facial expressions. Maybe they were too hard to draw, or too time consuming? The faces of Stardust and Fantomah are marvels of immobility; in a twist on the masked superhero, their own placid faces resemble masks. Stardust’s lips neither move nor open even as the action swirls around him—a kind of Clutch Cargo in reverse. The faces of his villains are equally static (except when said villains are being tortured by the hero), and tend toward the physiognomical: ugly, brutish faces equal ugly, brutish souls.

This, then, is as good a place as any to discuss Hanks’s drawing skills. If judged purely on things like scale or proportion or realism, he fails. Heads are too small for their bodies, and there is little feel for how people actually inhabit or move through space. Figures seem more like statues than living, breathing humans. Here is a partial list of things Hanks could not draw, or had problems drawing to scale: hands, arms, legs, wrists, torsos, bodies in motion, bodies standing in place, assorted mammals, black people. In his illustrated afterword, Paul Karasik has two characters—Karasik’s mom, and Hanks’s son—weigh in on the cartoonist’s work. “Looks like crap to me,” says Mom. “Looks like crap to me,” says Fletcher Jr.

It doesn’t look like crap to Paul Karasik, who places Hanks alongside George Herriman and Elzie Segar in the pantheon of comics artists. According to Karasik, Hanks was better than famed MAD artist Basil Wolverton, to whom his work is sometimes compared; many of his panels, he says, display a Magrittean stillness. When asked if the work would be better or worse if Hanks could draw better, Karasik seems genuinely bewildered by the question, perhaps even insulted. “I think he’s a great draftsman,” he says. “Would Martín Ramírez be a greater artist if he could draw better?” Touché!1

And really, who’s thinking about such details as head size, when there are lions and elephants being chased through the jungle by enormous flaming hands? Who cares if nobody’s lips move, when there are caverns crawling with white cobras, and gigantic tornado machines threatening the people of Earth? The weird proportions and hulkish figures are, in many ways, perfect for a comic that recalls nothing so much as the Pee-Chee folder scrawlings of a rage-filled schoolboy. One can imagine Hanks at fourteen, scribbling furiously in a notebook, imagining he is the vengeful Stardust. His gas bombs and atom smashers would be aimed at his high school; his hated teachers would be the ones flung into space.

In his afterword, Karasik travels to Maryland to meet Fletcher Jr., who is now in his late eighties. After relating a few unremarkable stories about his family and childhood and some horrific tales about his dad, Fletcher reveals the manner of his father’s passing. “The cops found him frozen to death on a park bench in New York City,” he says. In the next panel, Karasik recalls a comic in which Stardust imprisons the villain in “the floating prison of eternal ice.” “In your frozen condition,” says Stardust, “you’ll live forever—to think about your crimes!” If this were a conventional comic, there would be an appropriate visual or aural cue: a light bulb flickering on, or an audible whammo. Instead, there is only an image of Karasik, an empty thought-balloon dangling above his head. Here, then, is the poetic justice that Hanks, the weirdo cartoonist, had been striving for all along.

And now Hanks is being frozen yet again, preserved not as punishment but for posterity. It’s unlikely the artist’s chances of finding audiences anew will suffer from the tales of his past sins; rather, the savagery of his life only allows one more avenue of appreciating the savagery of his comics. As in the works of outsider artists from Adolf Wölfli to Henry Darger, there is a certain sublime pleasure in observing the madness on the canvas and imagining the demons dancing within the creator’s brain.

I Shall Destroy All the Civilized Planets! is dedicated to Hanks’s son, whose photo appears in the front of the book. In his hands is a lovely sketch of a flock of geese. The picture was drawn by his father, and it is the only piece of artwork that the son held on to after the man’s passing. The geese are taking a break from their migratory flight, relaxing on the icy surface of a frozen lake. And Fletcher Jr. is beaming.