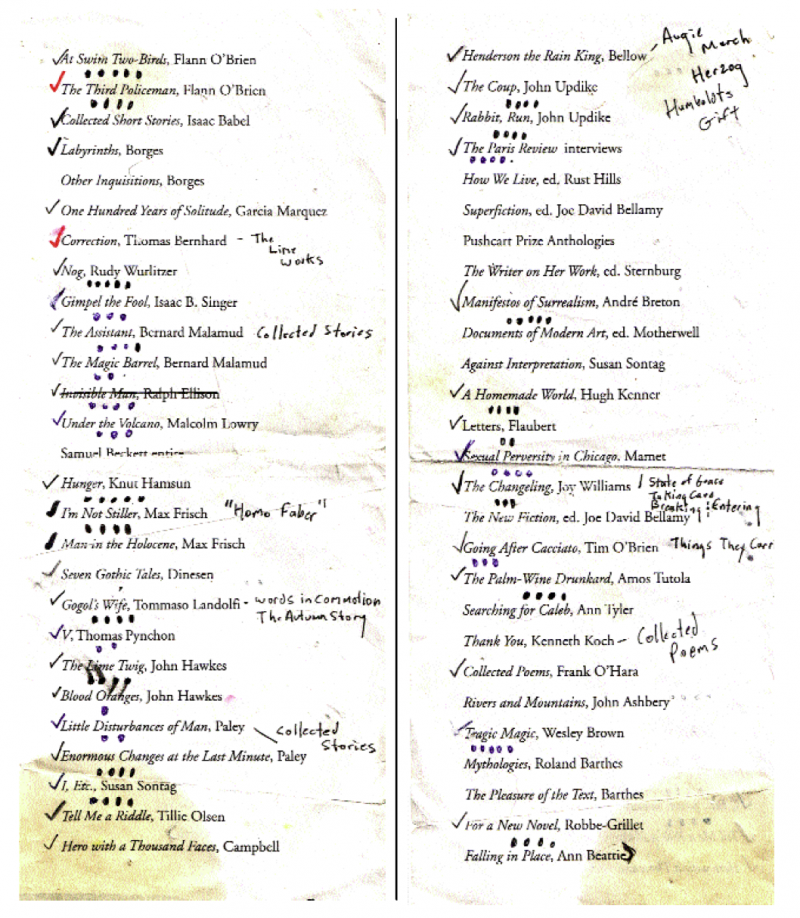

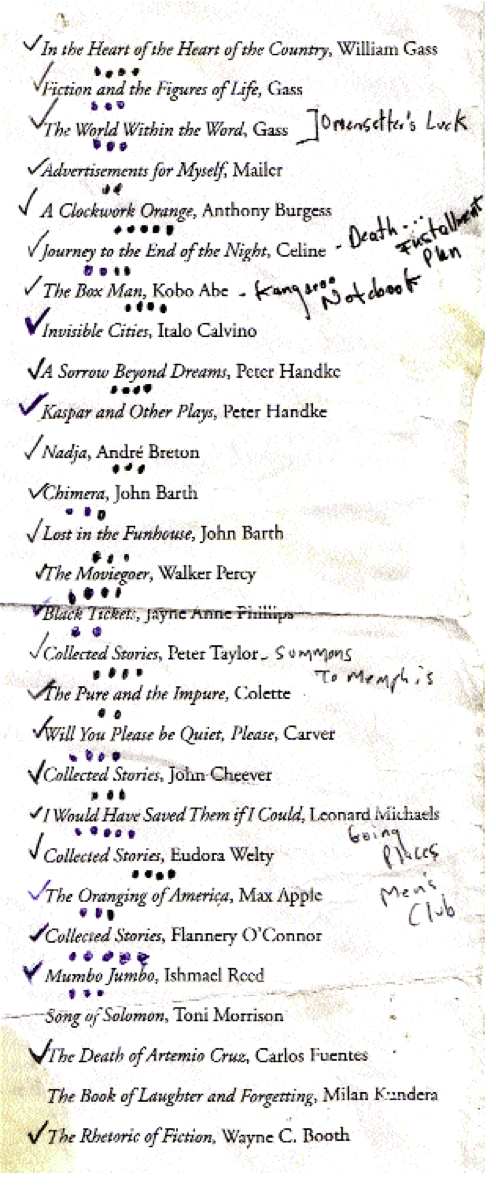

There was a time when I fought against an impatience with reading, concealing, with partisanship, the fissures in my education. I confused difficulty with duplicity, and that which didn’t come easily, I often scorned. Then, in my last year of college in Gainesville, Florida, I was given secondhand a list of eighty-one books, the recommendations of Donald Barthelme to his students. Barthelme’s only guidance, passed on by Padgett Powell, one of Barthelme’s former students at the University of Houston and my teacher at the time, was to attack the books “in no particular order, just read them,” which is exactly what I, in my confident illiteracy, resolved to do.

But first I had to find the books, a search that began at Gainesville’s Friends of the Library warehouse book sale. Early morning, the warehouse parking lot was filled with about fifty men, women, and children waiting for the doors to open. At the front of the line were the all-nighters, hard-core sci-fi fans, amateur Civil War historians, and chasers of obscurities, rumored to have been there since before midnight. Some had brought with them hibachis and coolers and battery-powered radios, giving the parking lot the feel of a Gator football pre-game with less angry hope.

When the garage door opened, I watched the all-nighters sprint into the warehouse, toward the wall-to-wall shelves and the sixty or so tables of books, the odor of dampness and dust. Some books were arranged by subject, others democratically, Dead Souls rubbing sleeves with Pregnancy for Dummies. By the time I made it inside, those ahead of me had already secured their spots: little kids rummaging through the picture books in the far corner, a guy in winter fatigues looking through the vintage Penthouses, a graduate student with an Ask Me About Postmodernism pin on his army-surplus backpack solemnly problematizing the literary criticism section.

The books on sale were mostly disused and shabby, dustjackets ripped or discarded, the stamp of the Alachua Public Library on their fly leaves and tape marks on the spines. Toward the front of the warehouse was a collector’s room with inscribed books by local authors like Harry Crews and Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, but the real activity was here in the aisles. As a section’s inventory ran low, library volunteers carted out cases of books from the front of the warehouse to replenish it. Shoppers rushed to help the volunteers unload the books, filling their own boxes as they did, often holding up and announcing their windfall. “Copy of Nabokov’s Lectures!” “Copy of Ariel!”

The first book I found was a pocketbook version of A Homemade World by Hugh Kenner (number 39 on the list), a scuffed copy full of wobbly underlining. Fifteen minutes later, I found The Oranging of America by Max Apple, Manifestoes of Surrealism by Breton, Celine’s

Journey to the End of the Night, Flannery O’Connor’s

Collected Stories (numbers 76, 36, 59, and 77).

I was shiftless and poor, so I switched the color-coded dots from more-marked-down books to less-marked-down books for a better deal. A shameful gesture, I know, and worse because of my new oath to literacy and because the books were each about two bucks to begin with. All told, I spent about fifteen dollars on the twenty-five books in my dishonorable grab.

With a tractable reading list in front of me my impatience with reading turned quickly into avidity. Saul Bellow’s Augie March, who also begins his attachment to books by stealing them, says about coming late to reading, “I had found something out about an unknown privation, and I realized how a general love or craving, before it is explicit or before it sees its object, manifests itself as boredom or some other kind of suffering.”

That object, the book on the list that turned my resolution into a vow, was O’Connor’s Collected Stories. I opened the book to “A Late Encounter With the Enemy,” a story I began doubtfully and finished stunned; never have my preconceptions about a book been so quickly burned into vapor. I saw: Irish name, cartoon peacock on the front cover, blurb on the back cover saying the stories “offer an unparalleled picture of the Deep South,” and I thought: stories about farming, probably characters lamenting the unpleasantness between the races and the overall dryness of things. There’d be ardent specificity about moonshining and crop rotation and hog-boiling. There’d be righteous hollerin’ between man-on-porch and man-on-dirt-front-yard.

Instead, here was hundred-and-four-year-old “General” Sash, twelve years off the preemy and damned tired of remembering; and Sally Poker Sash, his prideful granddaughter, praying that the old man lived long enough to serve as a monument of costume dignity at her college graduation for “all the upstarts who had turned the world on its head and unsettled the ways of decent living.” Concision, conviction, and vision: Here was an artistry I could appreciate, and be amazed by, without wholly apprehending it. Everywhere an unsentimental view of human weakness, with beautiful consequences. Mrs. May? Gored. Lucynell Crater the younger? Left sleeping at a diner. The fool and his turkey? Soon parted. The grandmother? Which grandmother? Doesn’t matter, doomed.

If the list’s books are skewed toward Barthelme’s particular obsessions—one of the entries is “Beckett entire”—this is only to its credit. Most are novels. All but two of the books, Knut Hamsun’s Hunger and Flaubert’s Letters (numbers 15, 40), were written in the twentieth century, most in the past thirty years. And all have that dizzying sense of otherness and surprise common to great books, an affluence of vitality. There’s not a dull read in the group: Wesley Brown’s Tragic Magic and Max Frisch’s I’m Not Stiller (numbers 50, 11), the former the story of a black conscientious objector during Vietnam, the latter a layered account of denied identity; the Paris Review Writers at Work interviews (number 31) in which Faulkner is asked, “Some people say they can’t understand your writing, even after they read it two or three times. What approach would you suggest for them?” His answer: “Read it four times.”

Difficult books inhabit the list, too. Thomas Bernhard’s Correction (number 7), for example, paragraph-less, with dense, pages-long, self-negating sentences, which move with the spiraling locomotion of thought; and Andre Breton’s Nadja (number 65), a mystifying short novel accompanied by mystifying photographs. John Hawkes’s The Lime Twig (number 21), which reads like a traditional novel thrown into a wood chipper and reassembled.

I read Barthelme’s own 60 Stories, not included on the list (none of his books are, an indication of Barthelme’s modesty), but a collection both rowdier and more urbane, funnier and wiser, than anything I had read before. “Me and Miss Mandible,” the journal entries of a boy-adult longing for his teacher among a classroom of sixth-graders: “Miss Mandible is in many ways, notably about the bust, a very tasty piece.” And Barthelme’s re-imagined Snow White, in which the command is given, “Revise your lives upward!” I heard truth beneath the jangle of comic exhalations, a hint of a world far more vigorous than the one I knew.

By summer, with the list half-devoured, I felt on the verge of a sort of worthiness. Because many of the list’s books were no longer in print, I spent a lot of time foraging around central Florida, in thrift stores in Micanopy, in estate sales in Palatka, and in Daytona Beach—where I was born, and where I found what would become one of my favorite places in all of Christendom, Mandala Books.

On Volusia Avenue, since renamed International Speedway Boulevard, next to a Lutheran church sits a used bookstore with kaleidoscopic mirrors and tie-dye psychedelia in the windows. I haven’t ever developed a rapport with Mandala’s employees, or its owner, who is fully bald, and whose name I don’t know. I know his mastiff’s name, though, Odessa, usually torpid in front of the travel book section. The owner is not happy to be in the used-book business. I once overheard him recalling to an employee how he’d rejected an offer to attend the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in the early seventies. He seemed both proud of and disappointed by this fact. He often comments on the books I buy. Saul Bellow is one of his favorites; he faults Barthelme and Robert Coover for being “too look-at-me cutesy”; once he shamed me for trying to haggle over Blotner’s two-volume Faulkner biography, which he said was already “piss-cheap.”

I found about a dozen of the list’s books, and a dozen or so not on the list. But if buying these old books seems like some small act of charity, finding a collection like I Would Have Saved Them If I Could by Leonard Michaels (number 73) leaves me exceedingly grateful—to the author, to Barthelme, to Mandala Books. Who could have predicted such rare verve sitting defused and harmless-looking among Judith Michael’s tales of passionate adventure and Fern Michaels’s tales of adventurous passion, in a store that resides among pawn shops and an Asian grocery store, just a few blocks away from a black billboard showing Dale Earnhardt’s Number 3 with goddamn angel wings?

When the summer ended, I knew at least two things I hadn’t before: Illogical resolutions are the most likely kept; and, whether or not this newfound endeavor had made me more interesting, it certainly made me more interested. “A blunder—apparently the merest chance—reveals an unsuspected world,” Joseph Campbell writes in Hero With a Thousand Faces (number 27), “and the individual is drawn into a relationship with forces that are not rightly understood.”

That summer, I still didn’t see through the haze of my good intentions. But I was beginning to understand what I did not know.