Central question:

Who, or what, is chasing you?

The scene is London, 2005: a city still fearful and jittery following the horror of the recent subway bombings. A newly pregnant and married redheaded Australian expat named Ann is riding the Tube when the train derails. It is a minor incident, with no major injuries, but in the confusion she winds up taking home a fellow passenger’s cell phone. When Ann and her husband, Tom, go to return the phone to its owner, a TV writer named Simon, they end up staying for tea with him and his wife, Kate, a “holistic therapist.” At first it seems like this over-earnest yuppie couple will be the kind of people Tom and Ann love to hate. They say “cappuccini” instead of “cappuccinos”; their children are named Titus and Ruby-Lou. Tom sees that this will be the kind of evening that they’ll make snide jokes about later on. Or, at least he thinks it will, until Ann shares a secret with these ridiculous strangers that she’s never shared with her husband: a man has been following her. Tom, who narrates the novel, relates the following exchange:

“Black or white?” Simon asked. She hesitated. “He’s a black.”

The racist-sounding use of the article alarmed me.…

I hated him all over again, turning the four of us into a bunch of middle-class, anxious white people with that simple “Black or White?” (All right, that’s exactly what we were, but how rude of him to point it out.)

A sense of unease pervades every scene, every conversation. Tom’s screenwriting career has dried up. He and Ann have just bought a house in Camden, gentrifiers in a “transitional” neighborhood, and they are mortgaged up to their eyeballs. A baby is coming. And now Ann is in danger, chased by a threatening presence that Tom has never seen and doesn’t know how to save her from. Soon everything will fall apart.

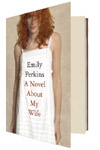

Tom is narrating the story almost five years in the future, in a document he calls “Novel About My Wife,” or “N.A.M.W.” Knowing that Ann will not be saved is what makes reading the novel a pleasantly excruciating experience. The slow-motion shape of the disaster coming is beautiful to watch. The reader knows before they do that Tom and Ann are falling. At the time he is writing, Ann is gone. Alone with his four-year-old son, Tom desperately tries to write Ann back into his world. “If I could build her again using words, I would: starting at her long, painted feet and working up, shading in every cell and gap and space for breath until her pulse couldn’t help but kick back into life.”

Novel About My Wife is a study of entropy and collapse, and the insanity of hypervigilance: one actually can go crazy with the knowledge that one is never completely safe. Jobs are lost, mortgages are defaulted on, marriages fall apart. Tom, trying to protect his wife from one alleged threat, ignores all the wrong ones. Emily Perkins has managed to write a novel about middle-class anxiety that is actually terrifying. The slow buildup is so well done, and so thoroughly uncomfortable, that once the mysteries are all solved (Who is following Ann? What is the alluded-to shocking event that occurred on their honeymoon?) the narrative flattens a bit—a minor quibble about an otherwise terrific novel. It’s unfortunate that Perkins didn’t end the story a little sooner, without explaining quite so much. Villains are always more threatening when they lurk in the shadows, unnamed.