1.

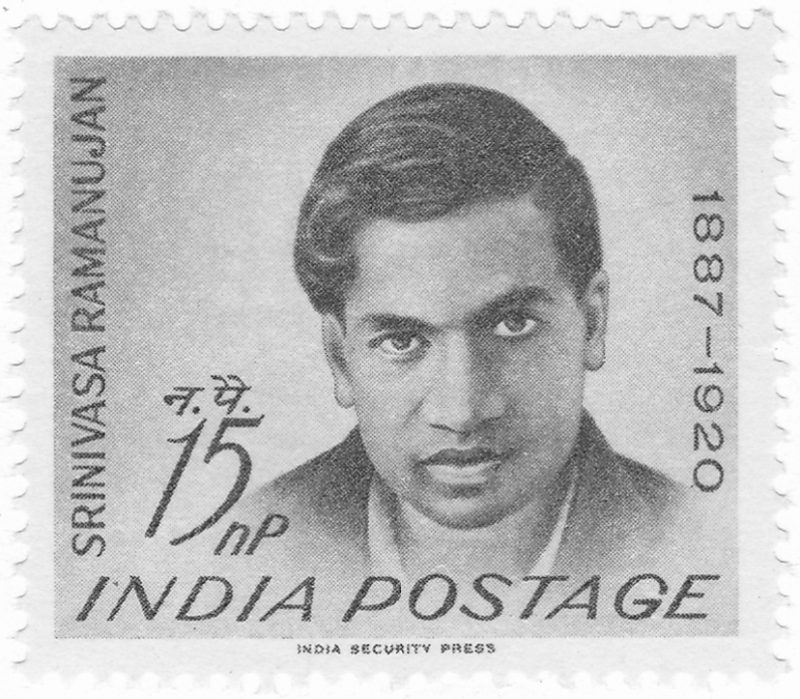

There is a form of Buddhism so potent, adherents say, that to hear its name spoken is to receive a promise of premature enlightenment, of early freedom from the wheel of incarnations. Something similar is true of Srinivasa Ramanujan, the super-genius who was born into deep poverty in an obscure part of southern India, who taught himself mathematics from a standard textbook, and in total isolation became a mathematician of such power that a hundred years after his death, at the age of thirty-two, the meaning of much of his work is still a mystery. In the middle of what I thought would be my life’s work, writing and producing music, I heard his story; now I find myself in graduate school studying number theory.

The story of Ramanujan is a variation on the same mythopoeic tale related in Star Wars and the New Testament, of a special boy born into adversity. A mother cannot conceive. The Goddess appears in a dream, promising a son through whom the God will speak to his creation. While pregnant, the mother travels to her ancestral home. During the winter solstice, the boy is born, under signs in the heavens that portend great events: his horoscope, cast by his mother, predicts that he will be a genius beset by great suffering. “Svasti Sri,” it reads, “when the moon was near the star Uttirattadi, when Mithuna was in the ascendant, on this auspicious day” Ramanujan is born. And indeed, his will be a short life, full of triumph and disaster. Growing up, he is gentle and quiet. Weightless is the word one of his childhood acquaintances uses in Robert Kanigel’s The Man Who Knew Infinity: A Life of the Genius Ramanujan. Beginning in his teenage years, Kanigel writes, Ramanujan “would abruptly vanish… Little subsequently became known” about these disappearances. Around this time, Ramanujan acquires a hoary old text (G. S. Carr’s Synopsis of Elementary Results in Pure Mathematics) that initiates him into the arcana. The Goddess begins to appear to Ramanujan in his dreams, showing him scrolls covered in strange formulae. “Nākkil ezhutināl,” he later said. “She wrote on my tongue.”

With such minimal training, Ramanujan rediscovers the mathematics of the preceding millennia. As he begins to make deep discoveries of his own, he writes to the learned men of the world, but his claims seem too extraordinary to be the product of a sane mind, so they ignore him. One of these letters happens to reach G. H. Hardy, a famous number theorist at Cambridge University and one of the only mathematicians in the world with the right mix of training and temperament to see Ramanujan...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in