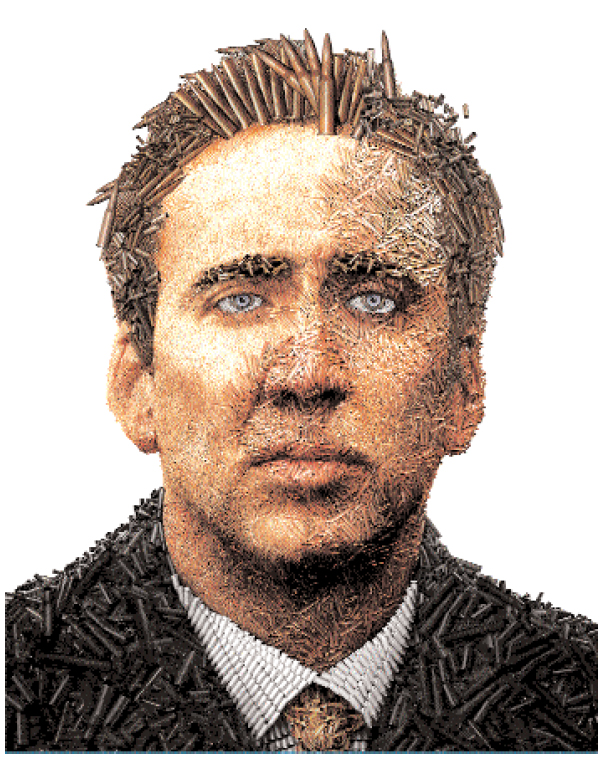

Look again at the advertising image for the recent Andrew Niccol arms-peddling-satire Lord of War: Nicolas Cage gazes dyspeptically out at us, but a moment hangs between us before we grok what is odd about the picture—Cage’s likable hangdog visage is composed entirely of tiny missiles, piled every which way and protruding like horned-toad armor. It’s easily the strangest poster image to accompany a Hollywood film in a decade—not simply because it fails to clearly peddle a rather unmarketable movie (there’s no concrete hint as to the film’s tone, genre, story, or thrust), but because as a visual it subverts a familiar pop-cult icon (Cage) in a manner far subtler than we’re used to (which is to say we’re used to being hit with pies), and because the strategy of the composition is inherently discomfiting, suggestively subatomic, evocative of the chaotic microcosmos around us: bugs, dirt, molds, germs, viral occupations, mitotic cells, electrons occupying two locations at once.

A similar frisson followed last year’s U.S. postage stamp design honoring R. Buckminster Fuller by way of transforming his bespectacled, brooding noggin into a giant geodesic dome squatting upon a futuristic landscape, a startling appropriation that would seem wildly daring for the USPS if it had not been used first as a 1964 Time magazine cover. The Fuller face summons its own suggestive queasiness—there’s an apocalyptic totalitarianism implied that has nothing to do with architecture or with Clive Barker’s Hellraiser—but it’s a paradigmatic example of a common, and perpetually disconcerting, cultural stroke: the face that isn’t a face. The upshot can be endlessly fascinating and disorienting, thanks to the role the human face plays in our psychosocial makeup. The verities of the face are encoded on our consciousness in such detail—an entire region of the brain, the fusiform gyrus, is said to be exclusively devoted to face interpretation—that no computer will ever, despite the premise of Niccol’s recent film S1m0ne, manage to duplicate it to our satisfaction. Of course, our ancient survival depended upon recognizing, reading, subreading, and remembering faces, and so the face, as an object, is the system of signs we know best and the closest thing we have to a unifying essential image.

So let’s fuck with it, inject unease into the intense syntactic dialogue a viewer has with another’s kisser, an approach that may’ve begun in the sixteenth century with Giuseppe Arcimboldo and his lavish canvases of fruit faces, book faces, fish faces, vegetable faces, and so on; cut to the late twentieth century, and there we have proto-Surrealist Czech animator-artist Jan Sˇvankmajer homaging the Milanese master with stop-motion fruit faces, book faces, seashell faces, etc.; and onward to Sˇvankmajer heirs Timothy and Stephen Quay, whose Arcimboldoesque contributions to Peter Gabriel’s “Sledgehammer” video were performed with great reluctance.

There are countless other examples before you get to the lowest basin into which every river flows: this year we’ve seen a TV commercial for Kraft Salad Dressing featuring an animatronic, talking Arcimboldo salad-head (onion nose, tomato cheeks, lettuce hair, etc.). The net effect is deranging at best. Advertising is, thank almighty God, an imperfect science—the science of brainwashing and emptying others’ pockets, albeit imperfectly—subject to ad writers’ egos and flights of fancy as well as market law, and so it’s impossible to scientifically ascertain to what degree the Kraft veggie-skull, or the Cage bullethead, actually sold their products. But my guess is that they haven’t very well, and in fact have done the near-opposite: mustered flummoxed wonder, shot themselves in the foot, generated consumer contemplation of a reptile-brain archetype gone squirrelly rather than thoughtless spend-lust. It’s comforting to know there are associative hiccups buried within us that even Madison Avenue cannot exploit.