In 1992, Wu Ruiqiu spread his paintings on a sidewalk in Guangzhou, the capital city of the Guangdong province of China. A stranger approached him and placed an unbelievable order: four hundred thousand paintings, to be delivered in fifty days. According to Wu, the client was Walmart, and the order, as the legend goes, was filled.

Ruiqiu was able to deliver the order once he assembled a team of two hundred painters in Dafen, a village in southern China that has since become the largest exporter of oil paintings in the world, the majority of which are replicas of Western masterpieces. Though Ruiqiu’s tale is perhaps apocryphal, the size of the order and the demand for handmade replicas from Dafen is a reality. Buy a furnished Florida condo and there’s a chance a Dafen painting will adorn your wall. Visit the National Civil Rights Museum at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis and note the painting hanging in the reconstructed motel room adjoining that of Martin Luther King Jr.—it was made a world away, perhaps the twentieth canvas completed that day by a painter in Dafen.

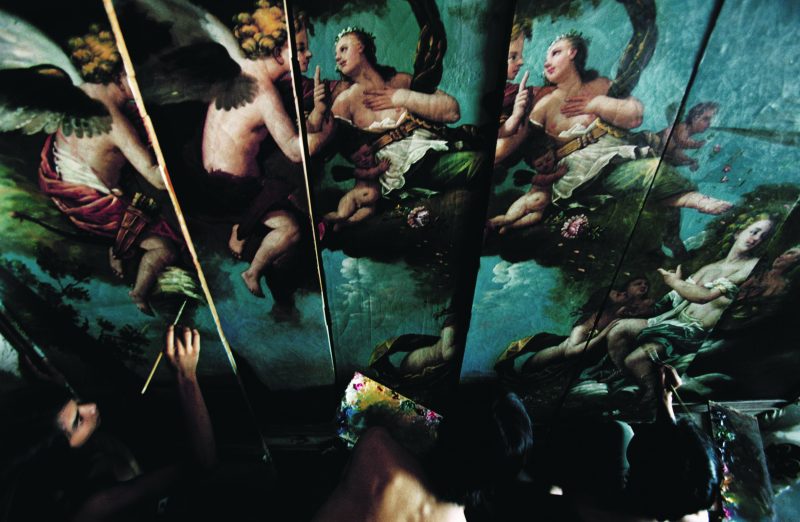

While reports in Western media often breathlessly suggest that Dafen represents a factory-like “assembly-line” approach to art, Winnie Wong, an author and assistant professor in the Department of Rhetoric at UC Berkeley, counters that Dafen painters, “like most modern and contemporary artists, work independently in their own modest homes and studios, and are paid for each painting that they sell.” For four years, beginning in 2006, Wong conducted field research in Dafen, and collected her findings in Van Gogh on Demand: China and the Readymade (University of Chicago Press). The Walmart tale appears in Wong’s book, as do the twenty instructions for how to replicate van Gogh’s Sunflowers, which she encountered as an apprentice painter. (Step 14: “Using a third 1/8″ brush, load with dark green pigment and freehand draw each leaf. Make it look natural, like a leaf.”)

I spoke with Wong this summer about the nature of copying. Appropriately enough, I recorded her responses and copied them here.

—James Hughes

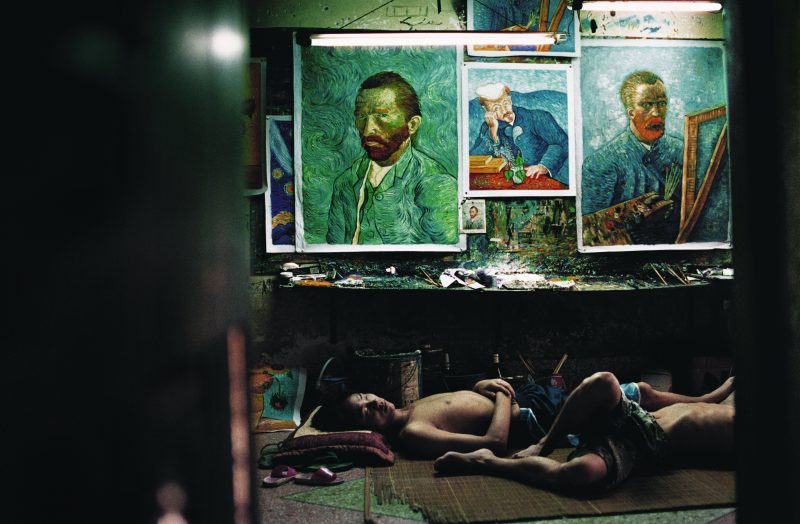

WINNIE WONG: In Dafen, almost none of the painters are specialists of a single Western artist. There are no Monet specialists. No Leonardo da Vinci specialists. Van Gogh is the only single artist who is a specialty in Dafen. One of the reasons he’s a specialty is because he’s considered the easiest to paint. When unskilled painters first came from their villages to the city in the late ’80s and early ’90s to begin their training, they started with van Goghs because they were in high demand and because they were easy.

My argument is that it’s also easy because what we want in a van Gogh painting is the presence of the hand. What van Gogh accomplished, in the most fundamental way, was to make his work about the hand of the artist, which we can see as a brushstroke very visibly on the canvas. It’s a crystallization of the van Gogh style and his value in the history of art. What my visit to Dafen showed me was that it doesn’t have to be van Gogh’s hand—it can be anyone’s hand.

I remember someone once asked if van Gogh would be proud to know how many painters his paintings are feeding. It’s a wonderful thought. Van Gogh was the painter of the potato eaters. He was concerned about laborers and the poor long before he became a painter. I think it’s a lovely development in the history of van Gogh—better than the fact that he never sold a painting and now they’re worth so much. The myth is usually that he didn’t sell a painting, and yet the paintings are now priceless, which is supposed to be somehow uplifting. But I actually have a lot of trouble with that story, because it means that a person can be completely out of his time and completely mistaken and yet be validated hundreds of years later, and it’s therefore made it possible for so many people to claim they’re great artists and don’t need any social or commercial validation whatsoever. The auction prices of the van Gogh paintings made that myth basically truth, and that had a major effect on who we think can be as artists. So I think it’s sort of wonderful and natural that so many farmers in China have become van Gogh painters.

One of the most unexpected things I learned about Dafen was that in so-called “copying” the paintings, they actually aren’t copying. They rarely look at the image that they are copying. I also heard from many painters that the smaller the image you give them to paint from, the better— the blurrier the better, the lower the resolution the better. The less you’re trying to follow something, the better the work. When Dafen painters talk about their individual flavor or touch, so to speak, that’s what it’s about. It’s about making a good painting, which—in the van Gogh style, at least— means having the brushstrokes of your individual hand in it.

We fetishize paintings as almost-religious objects: they can’t be moved, can’t be changed, can’t be the source of more work. We are obsessed with the notion that a work is so sacrosanct that it can never be touched or changed—so much so that we even police each other when we take photographs of works in museums. That wasn’t how art was understood, even in the West, until very recently. There are copies or repetitions or variations of almost every famous artwork we know. They aren’t unique. Even when The Scream was sold, that was only one of four! But we have this need to view these works as invaluable, unique objects rather than cultural or commercial products, or products of social relationships.

To imagine a place where people do nothing but copying is naturally, in the Western imagination, a very dystopic idea, because it goes so far as to violate our sense of what work means and what the self is—that our work is supposed to mean who we are. Once you accept that imitation is always a part of art, once you get over that bias, the flip side is that Dafen represents a place where anyone who works hard enough can be an artist. In that sense, Dafen can appear as a kind of utopia. In my own experience, I’ve seen the positive side more than the negative. The problem for Dafen is that it became a utopian model, which is just as fraught and problematic. In reality it’s actually neither of these things. The painters in Dafen are very aware of both the utopian and dystopian views of who they are and what they do, and they’re caught trying to deal with that.

When we say Dafen painters aren’t artists, we’re saying they’re not putting thought or mental labor into their work in the way we expect conceptual artists to do. I think a lot of people don’t like conceptual art, because there’s too much of that—privileged mental labor is held far above skill or other qualities. Conceptual labor is the moving target here, and it’s where we get to issues of global labor inequalities, or at least differences. How do you value mental labor? How do you see it? Who buys it? Who gets to express it? Dafen painters are simply not able to. They’re not able to mobilize the discourse.

I saw Ai Weiwei at a lecture in which this issue came up. He was asked what his craftsmen think of him selling these pots, which they had painted, for thousands and thousands of dollars. I thought it was revealing when he said his craftsmen don’t understand that there’s such a thing as an art market. It was that action of speaking for them as though they were stupid—I mean, is it really possible his craftsmen don’t know that there’s such a thing as an art market? A conceptual artist like Weiwei, who has to sell his conceptual labor as a thing that’s valuable, must therefore devalue the mind of his hands. What I’m trying to do is bring those two a little closer together.