Keri Smith may well be the self-help guru this DIY generation deserves. She elicits comparisons with SARK (Susan Ariel Rainbow Kennedy), whose Living Juicy: Daily Morsels for Your Creative Soul and Eat Mangos Naked: Finding Pleasure Everywhere (and Dancing with the Pits) ooze with a new-agey women-who-run-through-the-watercolors vibe, but trades rainbows for a hand-knit aesthetic that’s at once hip and deeply nonthreatening. As a self-described guerrilla artist, Smith flips Chekhov’s maxim that “if you want to work on your art, work on your life,” and the inversion seems to have struck a best-selling chord.

In a culture in which the value of everything from pickles to parenting seems increasingly dependent on viewing every undertaking as artistic, Smith gives her readers the tools to transform normal life into art, suggesting that this alchemy will make us happier. Her work taps into the special ability of art—narrative art most directly—to create a frame around seemingly mundane everyday activities, simply by changing the sort of attention we give them. Tell me I’m writing a book, and I’ll start narrating in my head. Call it, after Duchamp, the urinal effect.

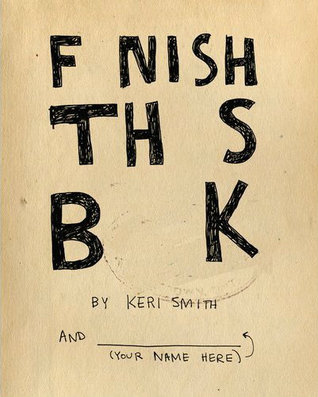

Smith’s latest art-activity book, Finish This Book, depends on this effect. Its lobbying for the aforementioned transformation stems from the opening of a kind of artistic attention, and intention, beyond whatever prompts it gives you. That is, because there are few limits to what can be included in the book—to how you can “finish” it—anything has the potential to become art through transcription into narrative, and so anything has the potential for the same value we’d ascribe to art.

Indeed, Finish This Book is less about making art than it is about an artisanal form of existence: cultivating inspiration, enjoyment, and meaningful doing. But “meaning” here is a fairly loose concept, judging by the lack of rules: messes, halting missteps, and out-and-out destruction are meaningful. So are disguising oneself, hiding in the woods, and keeping track of exactly what one has done during the day. So, obviously, is the meta-task of “finishing” this book.

But a book is not a traditional living space, and inviting imperfect daily activities into it calls for some renegotiation of boundaries. Despite the suggestion that anything can constitute meaningful and literary narrative, a narrative implies choice: at any given moment in the story, one can sit under this tree or that tree, but not both at once. And it’s quite possibly the choice of one path over another—the necessary boundedness of our attention—that makes art worthwhile in the first place.

This negotiation between limitless artistic intent and the intrinsic limitedness of art itself may explain why Smith’s book invokes artistic freedom courtesy of certain solid literary tropes. Finish This Book begins, “One dark and stormy night,” for one thing, and takes its epigraph from Italo Calvino’s If On a Winter’s Night a Traveler, the novel-that-insists-it-is-not-a-novel par excellence. Smith’s narrative, such as it is, kicks off from the discovery of scattered pages that turn out to belong to a book called The Instruction Manual, and solving its mystery—through tasks such as constructing a DO NOT DISTURB sign and brushing your teeth with your eyes closed—turns out to be the reader-cum-finisher’s objective.

As in Calvino’s novel, there is another book surrounding the Manual, one that engages the reader in intra- and extra-literary preparatory tasks: inventing characters and alter egos, exploring your surroundings for clues and inspirations, developing rudimentary code-breaking skills. This device is familiar enough by now that we aren’t really meant to believe in it, but it does suggest the spirit of wonder with which we are meant to approach the story—the same spirit with which Smith intends for us to approach her activities, and, ultimately, the rest of our lives. If the invented story might be true, the real world might prove just as wondrous.

Part of Finish This Book’s “Secret Intelligence Training” requires taking a walk in your neighborhood and making note of, then drawing, the colors, shapes, and objects you see on the ground. One day I noticed a few things and duly recorded them (sidewalk gum, a dragon drawn in chalk, a piece of unidentifiable rotting fruit); the experience did not feel contaminated by the kind of self-awareness that makes consciously “artful” tasks feel forced, until, while I was drawing the gum, it did. What had been gum fully present in its undesirable, dirt-collecting, shoe-sticking gumminess was now an ill-described blob in a book; still, absent this book’s tasks, I would not have been forced to choose the gum or to select it as part of this true-untrue narrative—making it, as art, both more and less real as gum, giving it a different kind of value. Out of artifice, the thinking goes, we arrive at a new breed of the authentic.