“Fiction is a bridge to the truth that journalism can’t reach.”

—Hunter S. Thompson

1.

I met Second City comedy legend Del Close only once before he died. Close, with his white wizard’s beard and menacing baritone growl, held court at his usual table near the back of Chicago’s Old Towne Ale House. As he was famous for doing, Close entertained the grizzled regulars and his own tagalong admirers with outrageous stories from his past. Tonight he was “reminiscing” about his experiences in a traveling midnight spook show called “Dr. Dracula’s Den of Living Nightmares,” which he joined during the early ’50s while still in high school. His duties, he said, involved running through the pitch-black theater and tossing handfuls of cooked spaghetti onto the unsuspecting audience while calling out, “A plague of worms shall descend upon you!” Several audience members fainted, and at least one, he told us with maniacal glee, “shat himself.”

Then he described the spook show’s brief stay in Wichita, Kansas. It was in Wichita, he said, that he visited the Dianetics Institute for a personal auditing session with founder L. Ron Hubbard, who at the time was still known primarily as a science-fiction author. Close was a fan of Hubbard’s novels, and the two men formed a fast friendship.

At some point during their meeting, Hubbard admitted to Close that he wasn’t sure how much longer he could keep his Dianetics operation afloat, as he was barely able to afford the property taxes.

“Well,” Close purportedly told him, “if you’re worried about taxes, you should just turn Scientology into a religion.”

The small crowd burst into laughter, though most of them had heard this particular anecdote dozens of times before. Later I grilled Close for more details. Surely his anecdote was an exaggeration at best, a tall tale at worst, but in either case not meant to be taken literally. He stroked his beard and smiled at me, amused by my interrogation.

“Just because it didn’t happen,” he finally said, casually lighting up yet another cigarette, “doesn’t mean it isn’t true.”

2.

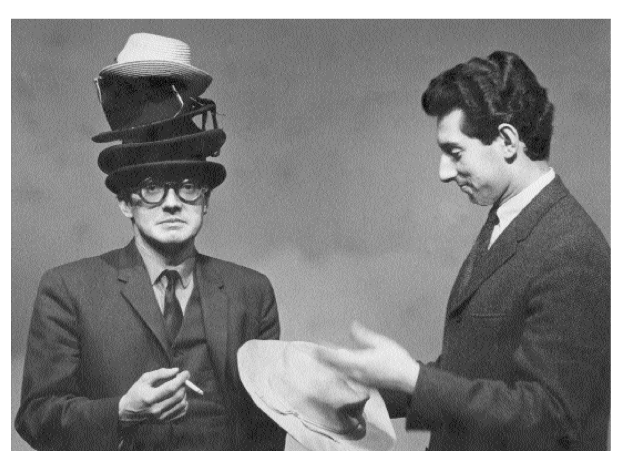

Bill Murray once called Del Close “the most famous man in comedy that nobody has ever heard of.” Although he remains largely unknown to mainstream audiences, Close is widely considered to be one of the most influential figures in the history of American comedy. During his forty-year career, he was present in the early periods of both the Second City and the Committee, where he single-handedly transformed improvisation into a valid art form. He discovered and nurtured generations of comedians, like John Belushi, Chris Farley, Amy Poehler, Martin Short, Harold Ramis, John Candy, Mike Myers, and countless others.

But the real legacy of Del Close can’t be found on his résumé. The stories that get told and retold about him have more to do with the strange details of his private life. Close was a notorious junkie, developing an addiction to alcohol, pot, cocaine, LSD, heroin, amphetamines, and a seemingly endless array of controlled substances. As Bob Woodward wrote of him in Wired, the controversial biography of John Belushi, Close “wore his track marks from the needles like a badge of honor.”

But drugs were only one small part of the Close mythos. Stories about his life range from the improbable to the utterly ludicrous. He claimed to have spent his teenage years working for a circus as a fire-eater (calling himself Azrad the Incombustible) and a target for a knife thrower. He produced light shows at Grateful Dead concerts, where he was billed as the “optical percussionist,” and later joined Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters. He cavorted in New York with Lenny Bruce and James Dean, hosted family dinners with Dwight D. Eisenhower, served as the “House Metaphysician” for Saturday Night Live, and shared drugs with Timothy Leary and G. Gordon Liddy. In one of his more infamous tales, he told of his supposed participation in dream experiments for the Air Force. When he left abruptly, he received dozens of letters from the government, containing only the cryptic demand, “You owe the United States Air Force one dream.”

Since his death in 1999, Close’s stories have become a permanent fixture in improv mythology. Not surprisingly, there have been numerous attempts to document his life. There’ve been two films, including PBS’s The Legend of Del Close (2000) and The Delmonic Interviews, a feature-length documentary that still screens on the national festival circuit, most recently at the Phoenix Improv Festival in April 2007. Bring Me the Head of Del Close, a stage show that consisted solely of performers telling stories about Close, played to sold-out crowds at the Strawdog Theatre in Chicago during late 2004. Jeff Griggs wrote a memoir, Guru: My Days with Del Close, about his experiences working as Close’s assistant and errand boy, and Kim Johnson—who, along with Close and Charna Halpern, cowrote the quintessential textbook on improvisation, Truth in Comedy—is reportedly working on a more comprehensive biography. Most famously, there’s Wasteland, the short-lived DC comic book that Close cowrote and considered his autobiography.

It’s not difficult to understand the posthumous feeding frenzy for Close’s life story. The only problem is, nobody seems to know with any certainty whether any of his stories are true.

While the verity issue was of no real concern to his friends, it came to matter quite a bit to me, a journalist asked to write a profile of Del Close for Chicago magazine. With Close already dead—one of the few verifiable facts about him—I had little choice but to base my article entirely on second-hand accounts. Everyone who so much as crossed paths with Close had a story to share, each more implausible and unconfirmable than the next. My sources consisted mostly of former hippies with sketchy memories, and actors prone to believe anything Close had told them.

Although I had a wealth of anecdotes, I wasn’t sure how to write truthfully about a man who had gone to such lengths to hide the truth. It was a daunting task, and by conventional journalistic standards, almost impracticable.

But it wasn’t the fact-checking dead ends that simultaneously fascinated and frustrated me. It seemed pretty obvious that Close had created, or at least embellished, most of his own mythology. The big question was why. Did he do it because he thought the fabrications were more provocative and exciting than reality? Or did he suspect that by blurring the line between fiction and nonfiction he was revealing more about himself than he could accomplish by sticking to the facts?

3.

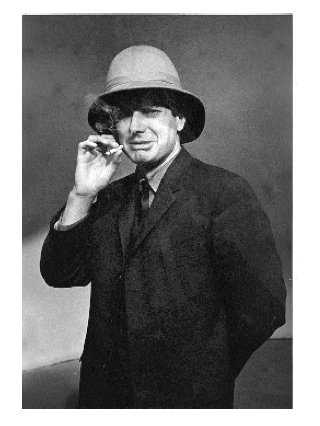

Let’s start with what we actually know to be true: Close was born on March 9, 1934, in Manhattan, Kansas, the only child of a jeweler and housewife. He attended Manhattan High School, where he was known by the nickname “Pickle” and was active in drama productions. Even as a teenager, he displayed a dark sense of humor. Archives of the Manhattan Mercury newspaper reveal that Close pulled off several elaborate pranks, including staging a fake shooting in which he appeared to be murdered. A 1950 high-school yearbook features a picture of Close holding a gun and preparing to, as the caption explains, “annihilate the cat that disrupted the T-Teen Play.”

After running away from home to join several touring shows, he eventually ended up in New York in 1958, where he pursued a career as a stand-up comic. He performed alongside Lenny Bruce, and later recorded two comedy albums, How to Speak Hip and The Do-It-Yourself Psychoanalysis Kit. He also dabbled in theater, appearing in a 1959 Broadway musical about beatniks called The Nervous Set, in which he played a yogi with a fondness for sexual experimentation.

Close moved to Chicago in 1961 to join the newly formed Second City Theater, performing with a cast that included Joan Rivers and Avery Schreiber. During his time there, he developed a taste for drugs, and on several occasions consumed a near-lethal overdose, which some of his peers speculate was intentional.

After being fired by the Second City in 1965, he traveled to San Francisco, where he worked at the Committee Theater, a North Beach performance troupe. He collaborated with Hugh Romney (better known as “Wavy Gravy”) on several projects, including a 1965 light show called “Lysergic A-Go-Go” at the Aeronautical Sciences Institute. He also participated in the “Acid Tests”—group LSD experiments sponsored by Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters—for which Close provided the psychedelic lighting. To subsidize his income, he commuted to Los Angeles to work in television, winning small roles in My Mother the Car, Get Smart, and others.

Wavy Gravy, who shared an apartment with Close in San Francisco, recalls returning home to find Close passed out on the floor from an apparent overdose. “There was a chart lying on his chest,” he said. “It was a list of different drugs, and he had checked them all. I was sure that he had OD’d, so I called up [Committee member] John Brent. I asked Brent what to do, and he told me to throw the I-Ching on his chest. Sure enough, he started breathing again.”

Close was rehired by the Second City in 1972, this time solely as a director. Over the next few years, Close trained such future comedy stars as Dan Aykroyd, Gilda Radner, Betty Thomas, George Wendt, and John Candy. But it was John Belushi who was most influenced by Close’s self-destructive nature. Close introduced Belushi to harder drugs, and the two became inseparable, frequently disappearing for days at a time in Close’s small apartment across the street from the theater.

In 1978, Close admitted himself into the Schick Shadel Hospital in Fort Worth, Texas, and after a treatment of aversion therapy, he was finally able to beat his alcoholism. But even sobriety did not tame Close’s worst instincts. As Close said in an interview with the now-defunct Chicago Theatre Monthly, “I’m never going to give up marijuana.… I take hallucinogenics maybe three or four times a year. But those are health drugs. Those are the things that are actively good for you.”

In 1982, just a few days shy of Close’s forty-eighth birthday, John Belushi died of a combination heroin and cocaine overdose in a Hollywood hotel. Close was devastated by Belushi’s death, and sank into a deep depression. He continued to direct at the Second City, but his passion for the work had dissipated with the loss of Belushi.

Rather than turn to counseling, Close found renewed inspiration in unlikely places. He immersed himself in the occult teachings of author Aleister Crowley and became the Warlock at a local Wiccan coven. Close was so enamored by his new spiritual beliefs that he began drawing on Wiccan rituals for his improv workshops at the Second City.

Close introduced his students to an exercise called the Invocation. Rather than inhabiting a character, he told them, they simply needed to invoke their qualities, conjuring up classical archetypes from mythology. In some invocations, students would take an ordinary object and find the “Chaotic Magik” within it, first by directly addressing the object and then, finally, by becoming that object.

Feeling that he had limited freedom at the Second City, Close began teaching workshops at art galleries and any space he could afford to rent. While teaching at CrossCurrents in 1983, he met a young producer named Charna Halpern, who had recently opened a new theater called ImprovOlympic with former Compass Player David Shepherd.

In a matter of years, ImprovOlympic became one of the most prominent training grounds for improvisers, launching the careers of Andy Dick, Chris Farley, Andy Richter, and Mike Myers. Though hardly a household name, Close was now considered a cult icon in improv circles. His newfound fame and stage success brought him small roles in films like The Untouchables and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off.

In addition to teaching, he also directed occasional shows at ImprovOlympic, most of which explored his favorite subject: death. In a 1989 show called The Horror, Close pushed his actors to create improvisations that inspired more terror than laughter.

“The whole point was to horrify the audience,” said Matt Besser, a costar of Comedy Central’s Upright Citizens Brigade who performed in The Horror. “Not in a silly, goofy way, or a ‘we’re going to tell a ghost story’ way, but to truly horrify and desensitize the audience. We took a particularly tragic story from the day’s newspaper and improvise around it. It had absolutely nothing to do with comedy. We all committed to it and tried our best, and it was horrifying. Out of the twenty shows we did, roughly half of the people walked out. And Del loved it. He just delighted in having this sort of power over an audience.”

During much of the late ’90s, Close’s health began to deteriorate, and he was eventually diagnosed with emphysema. When it became apparent that his time was running out, Close decided to host a final party, which he called a “Living Wake.” The event was attended by hundreds of his celebrity friends, and hosted by Bill Murray, the self-appointed Master of Ceremonies. For his last meal, Close was served a chocolate martini; his first taste of alcohol in almost twenty years. The next morning, Close requested a lethal dose of morphine and died shortly after sharing his final words: “I’m tired of being the funniest person in the room.”

4.

There’s an old joke about Close that many of his former students still like to tell. To create your own Del Close story, just randomly combine an obscure celebrity, an illegal drug, and a year. For instance, “I was doing crystal meth with Larry Hagman back in ’74…” Try it a few times, and you might stumble across something that could’ve come straight from Close’s mouth.

But the joke, as ridiculous as it might be, points to a genuine problem with most of the stories surrounding Close. At times, his life seemed like something out of MadLibs. For every anecdote involving, say, his onetime girlfriend Elaine May, there are dozens of similar stories featuring a rotating cast of famous friends and cohorts. Did Close dig up a child’s skull in Martin Short’s backyard, or was it while traveling with a Shakespearean theater company in West Virginia? When he went roller-skating through the sewers with an acetylene torch taped to his head, shooting at rats while conversing with LSD-induced hallucinations, was he accompanied by Wavy Gravy or Timothy Leary? And did this happen in Chicago or San Francisco? Ask three different people, and each one is liable to give you a different version.

And then there are the tales that, while remaining somewhat consistent, seem to have been invented out of thin air. Like this one: When Close was living in San Francisco, he once disappeared for several weeks without a trace. His fellow actors at the Committee Theater became concerned, and went to his apartment to check on him. After knocking at the door, they heard Close yell out, “Go away, I’m busy!” Fearing that he may have overdosed yet again, they broke inside and found Close dressed in a Spider-Man costume, suspended six feet in the air and tangled in a thick web of ropes.

“Look,” he told them. “I’m just trying to work some things out.”

A great yarn, to be sure, but nobody has the foggiest idea which Committee actors were actually involved. Most heard the story from a friend of a friend of a friend, which, like any urban legend, makes it all the more suspicious. There are a few who swear that Close himself was the first to tell it, which only lends further credence to the theory that Close was the sole architect of his own myth.

If nothing else, Close certainly delighted in retelling his stories. In fact, he was the first to begin documenting them for posterity. In 1987, he collaborated with artist and writer John Ostrander on the comic-book series for DC called Wasteland. Although intended as a mix of fact and fiction, most issues featured at least one autobiographical tale from Close’s life. The supporting players (all supposedly based on real people) included voodoo priests, gun-wielding rednecks, undercover CIA agents, and drug-fueled crooks and transients.

Even Ostrander, who formed a lifelong friendship with Close, wasn’t sure if he believed any of the stories. Close seemed equally unclear, and often ended each comic with the disclaimer “This story is maybe 75 percent true.”

“Del was a man who worked from behind masks, in both his creative and his personal life,” Ostrander told me. “The facts just weren’t that important to him. He would say that if reality doesn’t fit, then you should change it. You alter the facts to get to the truth of what a story was about.”

There is, of course, the possibility that Close’s life happened exactly as he described it. But ample evidence suggests that this was not the case. “The stories changed from person to person and era to era,” Jeff Griggs, who spent several years researching Close’s life for Guru: My Days with Del Close, told me. “If you talked to someone who knew Del in the ’70s, the stories were pretty basic. But if you talked to people Del had known in the ’80s or ’90s, the same stories were a little more magnificent and incredible. They were essentially the same stories, but Del just got better at telling them.”

A careful study of Close’s life stories reveals that he constantly revised them, added new characters, fine-tuned the laugh lines, and punched up the endings. The stories may not have originated as fiction, but after he had tinkered with them and reworked them, tweaking them into a more dramatic shape, they might as well have been.

Close did such an excellent job of rewriting his life that he left his biographers little choice but to follow his lead. Whatever truth there was to his stories is now hopelessly muddled in exaggerations. And what’s more, the new and improved versions are, in some ways, better than the truth. Close was a gifted storyteller, and he knew how to keep an audience captivated. Even the most ethical journalist couldn’t resist getting swept up in Close’s fantasies. Who wouldn’t want to believe that his life really was as colorful as he claimed? True or not, it made good copy.

As I worked on my profile of Close, I began to feel that I had been inadvertently cast as Close’s coconspirator. I wasn’t writing an objective account of his life, but piecing together the stories that he had already polished and preapproved. It was like I’d been given the task of finishing a dead author’s unfinished manuscript.

Stranger still, now that the fiction light had been switched on in my brain, I was no longer interested in separating the truth from the forgeries. As John Ford said in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” If Close’s life really was just a work of fiction, then surely there must be a thematic through-line. Sure enough, as I began to gather more pieces of the puzzle, a larger narrative began to take shape.

5.

Of all Close’s stories, the one that most defined him was his father’s suicide. As he told it, his father called him into the kitchen and announced that he intended to kill himself. He then drank from a glass of jewelry acid and died in front of his adolescent son.

Over the years, the details of his story began to change, and several friends have heard wildly different variations. Some say that Close’s father drank sulfuric acid, while others claim that he died from consuming Drano. A few insist that Close witnessed the suicide in the family kitchen, while some believe that Close was not in the same room. Close’s age at the time of his father’s suicide is also open to debate, with different versions having him at anywhere between six and seventeen years old.

It’s impossible to confirm exactly what happened. According to a Kansas state law, only family members and legal representatives are given access to death certificates. But some clues can be found in an obituary published in the Manhattan Mercury. Close’s father passed away on December 16, 1954, after being found unconscious in his jewelry store. Although the specific nature of his suicide is not provided, the report does mention that the cause of death was “self-inflicted.”

Even if Close was not entirely truthful about the facts surrounding his father’s death, it clearly had a profound impact on him. David Pasquesi, a Chicago actor who worked with Close at the Second City, told me that Close became more obsessed with his father’s memory as he approached his fiftieth birthday.

“His father died at that age,” he said. “It was like Del was thinking, Well, that’s what the Close men do when we reach fifty. We die. It was something that, in a strange way, he was kind of anticipating.”

Close’s thoughts of death may have grown stronger as he reached middle age, but it was by no means the first time that he had grappled with mortality. In a Second City scene from the ’60s called “Family Reunion,” Close turned to his father’s death for inspiration.

“I was essentially playing my father,” he wrote in Something Wonderful Right Away, a 1978 book that chronicled the early years of the Second City. “[It] was rather emotionally wearing because my father was a suicide, and he would come alive inside of me and it was rather frightening.”

Close once claimed that he and fellow Second City performer Severn Darden spent their free time competing in suicide contests, each trying to outdo the other with more outlandish and complex plots for their own deaths. When the Second City traveled to London in 1962, right in the midst of the Cuban Missile Crisis, Close devised a new game called “Gotcha” to help his company cope with its anxiety. Players were allowed to point a finger at any performer and pretend to shoot them. The “victim” was then obligated to fall in as dramatic a fashion as possible.

Avery Schreiber told a local theater weekly that Close was by far the favorite victim, never failing to deliver the most enthusiastic death scenes. “[He was] shot in the dressing room of the Establishment nightclub” where Second City was performing, Schreiber said. “He tumbled down eight flights of the circular stairway to the backstage area without stopping.”

Close’s infatuation with death and suicide only became stronger when he met John Belushi. He used the young comic to bring many of his darker ideas to the stage. In one scene, Belushi played a taxidermist who brings his fiancée home to meet his parents, who are both dead and stuffed. In another, Belushi performed a character based on Close who predicts his own death.

“And by then the needle will be in my arm and I’ll be six feet underground,” Belushi announced to the audience. “And there’ll be nothing you can do to stop it.”

As Close soon discovered, not everybody at the Second City was quite so willing to help him exorcise his personal demons. Dave Thomas, best known for his Doug McKenzie character on the Emmy-winning SCTV series, remembers clashing with Close over a scene involving suicide.

“We were in rehearsals for a new show,” Thomas said. “He got onstage and told me to play a doctor who had just informed him that his father had died from drinking sulfuric acid. And then he said, ‘Incidentally, my father did die from drinking sulfuric acid.’ I refused to do it and Del got pissed. He said, ‘Theater is not a democracy,’ and I said, ‘Yeah, well it’s also not some psychotherapy session for you to work out all the sick shit from your personal life.’”

Close’s father continued to be a recurring motif in his work throughout the ’80s and ’90s. At the Second City and ImprovOlympic, he often encouraged his actors to use the story in their improvisations. And though he never dealt directly with his father’s presumed suicide in his Wasteland comics, there were several tales that drew on it as a thematic device. In the first issue, a group of characters experiment with a new drug called “foo goo” which causes an instantaneous death. “The only sure thing,” one of the characters says, “is that one taste will kill you.”

Some of his students suspect that Close’s dark sensibilities had to do less with comedy and more with his need for a creative catharsis. He told them that it was an actor’s responsibility to relive his worst nightmares for the amusement of an audience. Art and life, he said, were one and the same.

While directing at the Committee Theater, he once painted “Follow the Fear” on the back wall of the theater. “He wanted actors to look out over the audience and see those words while they were improvising,” remembers Bret Scott, a onetime Close student. “That was pretty much his philosophy in a nutshell. If there’s something that makes you uncomfortable, something that scares you, then that’s the direction you should be going. Fear and truth are inextricably intertwined.”

As I continued to interview his friends and colleagues, I began hearing rumors involving his final days. There were occasional references to “The Big Suicide,” though nobody would elaborate on exactly what this meant. One of the producers at the Second City told me that I should be asking more questions about his Living Wake, insinuating that there was more to it than met the eye.

“Let’s just say that I’ve heard things,” he said. “I’m not sure if there’s anything to it, but some people think Del was hoping for a pretty dramatic exit.”

He suggested that I contact Tim O’Malley, a former Second City actor and, like Close, a recovering alcoholic. O’Malley was more than happy to share his theory. Close, he said, was taking a big chance with the martini he requested for his Living Wake. Because of the aversion therapy that Close underwent during the late ’70s, there was a possibility that drinking alcohol, even a single sip from a martini, would have been enough to kill him.

“I think that’s what he wanted,” O’Malley told me. “I never spoke with him about it, but I know he was very interested in orchestrating the exact timing of his death. It just seems to make sense.”

Dave Wick, an admission counselor at Schick Shadel Hospital, was quick to dismiss this claim. “There’s not even a chance,” he said. “After taking our treatment, patients have a negative response to alcohol, but they wouldn’t become ill if they took a drink. They may throw up, but even that is extremely rare. And there’s no way that it would have caused Del any physical harm.”

Though medically impossible, it’s still open to speculation what Close’s intentions might have been. Though most of Close’s colleagues hotly deny the rumor, some are willing to concede (off the record) that it certainly sounds like something Close might do. As O’Malley points out, “If you know anything about Del, it’s not completely off the wall. Just because it couldn’t happen doesn’t mean he didn’t hope for it.”

The suicide rumor has been repeated often within improv circles, evolving into another “Del Close Myth,” as unbelievable and yet as revealing as any of Close’s most far-fetched stories. From a purely hypothetical standpoint, it’s not irrational that a man dying from emphysema might consider suicide. But there is a world of difference between a suicide and a staged suicide. The former is a very private and personal decision, while the latter requires an audience. If Close had simply wanted to off himself, he could have accomplished it easily enough without the theatrics. Even if he never intended his death to be a public performance, it’s possible that he wanted people to think he might. Once again, he was asking his students to “follow the fear,” even if the fear was entirely manufactured.

If you dig even deeper, it’s difficult to miss the similarities between Close’s supposed final suicide and his own father’s alleged suicide. All of the same elements were there: a father figure, a gathering of children (his students), and a sudden death after drinking a toxic liquid. For a man who had spent so much of his life trying to make sense of his father’s actions, there was an almost arguable logic to it. How better to understand that moment than to re-create it? To truly experience it?

6.

The fact-checkers at Chicago magazine didn’t share my enthusiasm. They were hoping for something more reliable than a suicide conspiracy based solely on conjecture.

“But don’t you get it?” I argued with them. “The fact that the martini didn’t actually kill him is beside the point. His entire life was an invention. He constructed it like a play, and this is the perfect third act. Thematically, it just makes sense.”

They didn’t agree, and a radically altered version of my article (sans the purported suicide) was published in 2003. It covered all the bases of Close’s career, but it still felt like a failure. Nothing in my profile really captured the man. Ironically, by cutting all of the lies, my profile had been bleached of any truth. Close was as much a work of fiction as he was a real flesh-and-blood human being. Without the myth, the man ceased to exist.

There was some grumbling from the Chicago improv community that I had focused too heavily on the darker aspects of his personality. As I soon learned, most of Close’s friends are possessive of his legacy. They have a blind belief in the stories that Close chose to share with them, and an inherent distrust of anything that contradicts their unique rendering of his life. They believe that they and they alone know the true Close, and anything that strays too far from their accepted notions of him is nothing short of heresy.

But in the end, I wasn’t concerned with how the Chicago article was received. The real torment was realizing that I had so many great stories and nowhere to put them. I suppose that I could’ve just turned them into fiction, but then they would have lost some element of truth. If I tried to write the profile again, with all of the crazy stories and inflated myths intact, there isn’t a respectable magazine that would touch it.

I’ve long since given up any hope of writing the definitive Del Close biography. But the stories stay with me, like constant companions. If nothing else, they make perfect fodder for bar conversations. When I’m drinking with friends, I’ll share a Del Close tale or two, and they never fail to get an enthusiastic response. Occasionally somebody will scoff at my story, dismissing it as another urban myth, too ridiculous to be believed.

I’ll only smile at them, saying nothing. If Del Close taught me nothing else, it’s that a true storyteller never winks at his audience.