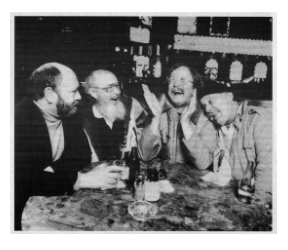

Starting in the late 1960s, a group of writers got together every Friday night at Enrico’s, a tiny café in San Francisco’s North Beach neighborhood. Sometimes they talked about writing, but mostly they drank, reminisced, and traded insults—the hallmarks of male bonding. The group’s personnel came and went, depending on who showed up to shoot the breeze and liquor up, but the core remained the same: Curt Gentry, the lesser-known coauthor of Helter Skelter; Evan S. Connell, who had risen to literary acclaim with Mrs. Bridge; Richard Brautigan, author of the cult novel Trout Fishing in America; and Don Carpenter, who would eventually mine a decade’s worth of these get-togethers for his final novel, Fridays at Enrico’s.

Brautigan was the de facto leader of the quartet. With his six-foot-four-inch frame, potent charisma, and celebrity, he attracted legions of hangers-on and beautiful women who might not otherwise darken Enrico’s door. Carpenter, on the other hand, was the wingman, whom Brautigan’s conquests turned to for insights into their lover’s mind. The supporting-player motif extended into Carpenter’s writing career: after initial success with his debut novel, Hard Rain Falling (1966), the seven novels, two short-story collections, and many screenplays that followed met with critical acclaim and commercial indifference, yet aspiring writers were eager to pick his brain on the craft of writing, the vagaries of Hollywood, and how to persist at putting words on the page when recognition continued to wait around the corner.

Born in 1931 in Berkeley, Carpenter spent his teenage years in Portland, Oregon, frequenting its pool halls and racking up, at most, an overnight prison stay on minor charges. A stint in Kyoto during the Korean war working at the Army newspaper Stars and Stripes (alongside a young Shel Silverstein, the paper’s cartoonist and an intermittent friend of Carpenter’s over the next two decades) cemented his desire to write. Several unpublished manuscripts and teaching gigs followed, as did marriage and two children, before Hard Rain Falling’s publication.

A year before Carpenter’s 1995 suicide, Anne Lamott dedicated her writing memoir Bird by Bird to Carpenter, a neighbor of hers in Mill Valley, California. He appears only a handful of times in the book—usually by last name—but Lamott brings him to life with a few sentences that betray a wicked sense of humor. In one anecdote, Lamott describes calling Carpenter up and asking his advice on how to handle a writer in the throes of envy. He said, “I just listen. They all tell me these incredibly long, self-important, convoluted stories. And then I say one of three things: I say ‘Uh-huh,’ I say, ‘Hmmm,’ I say, ‘Too bad.’” Then, Lamott continues, she starts telling him about her own bout of literary envy. “He was silent for a moment. Then he said, ‘Uh-huh.’”

Lamott hails Fridays at Enrico’s, a sprawling work set among the San Francisco literary community, as “a masterpiece.” The book has never been published, and until this fall’s republication of Hard Rain Falling, Carpenter’s other books had been out of print for years. Lamott’s memoir, on the other hand, has sold hundreds of thousands of copies and is considered something of a bible for aspiring writers.

Norman Mailer, an occasional visitor to Enrico’s, declared a later work of Carpenter’s, A Couple of Comedians, the best Hollywood novel he’d ever read. More recently Carpenter has been championed by Jonathan Lethem and George Pelecanos, the latter remarking that Hard Rain Falling “is on par with Edward Bunker’s Little Boy Blue in its shocking depiction of juvenile delinquency and the human cost of incarceration.” (Pelecanos also wrote the introduction for the book’s reissued edition.) So why has it taken so long for Carpenter to come back into the spotlight?

I.

Hard Rain Falling showcases the tough-minded, direct prose that would be Carpenter’s hallmark. It’s the opposite of a bildungsroman: antihero Jack Levitt comes of age, but he embraces criminality instead of enlightenment. A prologue depicting Levitt’s turbulent conception echoes Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy while also foreshadowing Levitt’s inexorable slide, his education honed in poorly maintained orphanages and on the streets of Portland and San Francisco. No wonder Levitt’s initial juvenile incarceration instills in him an overwhelming sense of absence: “It was one thing to know that you had been asleep all your life, but something else to wake up from it, to find out you were really alive and it wasn’t anybody’s fault but your own.” The slumbering life Levitt describes, a pungent blend of the poolroom and the bedroom, sounds plenty lively, but Carpenter is merely foreshadowing the book’s main section, which comes after Jack assaults his way into several years at San Quentin.

Jack’s earlier imprisonment was a badge of honor to be enjoyed, but now harsh truths overwhelm the older, wiser man. He can’t despise anyone: not his fellow inmates, who taunt him with homosexual overtures and threats of violence; not the wardens with their cruel abuses of power; and certainly not the outside world. So he turns the feelings inward: “He was getting older. The boredom of it all, the sameness, the constant noise and smell of the tank, were driving him crazy. The fact that he was in was driving him crazy.… He hated them all. But it was crazy to hate them. So he decided he was going crazy.” By choosing to go crazy, Jack lets himself off the hook from wanting more: “To think any other way was to hope, and he hoped he had given up hope.”

Hope arrives in the form of Billy, a former pool prodigy Jack knew in his twenties. As cell mates housed in the tumultuous maximum-security environment, where sex is used either as survival instinct or power grab, Billy and Jack’s shared past segues into a liaison equal parts hostile and tender, dismissed by both men as a temporary salve. Only after tragedy strikes does Jack realize how strongly he averted his eyes from love, in a paragraph that is all pounding rhythm:

Jack had not been loved as a child; he had not even been liked. And it had almost destroyed him. He had been nothing until he had been loved. From that moment… his life had begun to improve, and with only a few setbacks, it had kept improving. The more he loved and was loved, the better his life got. At once it seemed to Jack like a magical solution to everything. If only everyone loved everyone else! Then there would be no trouble in the world.

Only by accepting himself and his flaws can Jack move forward in his life, move past societal expectations, and embrace his true self. Others may have a temporary upper hand, but, as a rival of Jack’s realizes late in the novel, such victories are illusory: “What he really wanted was to endure, to live forever. It was the penalty you paid for living for pleasure, for yourself. You lived so beautifully that when you came to die…” The unfinished thought resonates. Despite the urge to focus only on elusive beauty, ugliness always lurks, just past the hiding hand.

II.

Carpenter sharpens up the shards of human cruelty even more in Blade of Light (1968), the mirror-image follow-up to Hard Rain Falling. Where the latter was a commercial success, the former flopped. Hard Rain Falling’s prose is just dense enough to be powerful, while Blade of Light layers so much imagery and allusion that its 180-odd pages feel twice as long. The story bears a surface (and a titular) similarity to the movie Sling Blade: a disfigured, possibly mentally challenged young man is let out into the world after being incarcerated for an unnamed crime; a tentative, foreboding reintegration into society follows. Semple is a tragic figure, and Carpenter generates sympathy for his protagonist by depicting his high-school humiliations at the hands of cruel, unthinking tormentors, but Blade of Light’s story line cannot quite bear the weight of the Faulkner-tinged prose. Speaking about the book’s failure in a 1975 interview with a journal called the Writer, Carpenter is both aware and defensive of his book’s faults: “Blade of Light is not an easily accessible story. It’s a very complex, extremely literary, highly compacted story and a much constructed story. I write very densely. Every word is connected to everything else. And I just knew that there were not going to be a lot of people who cared about this book. But the ones who did really dug it.”

The reception for Getting Off (1971), Carpenter’s third novel, was markedly different—perhaps reflecting the author’s own marital troubles (he would separate from Martha, the mother of his children, a few years later, though the marriage was never officially dissolved) and an evolution in style that would see his prose move away from Faulknerian aspirations. This entertaining and clear-eyed short novel depicts the abrupt end of a marriage between Jerry Plover, a disc jockey and minor San Francisco celebrity nearing forty, and Thalia, a bright woman who followed all the rules and found herself, eleven years and two children later, wanting more than housewifery in the suburbs could ever allow.

Plover’s shock at Thalia’s request to end the marriage is palpable: “It terrified him now suddenly to think of being alone, and the irony of this was that he so often in their married life hungered to be alone.” But despite his initial terror, which catalyzes a caustic, sometimes bawdy odyssey of newfound singlehood, Plover cannot condemn Thalia for wanting “a chance to live before she is too old.” Instead, he empathizes, whether in the midst of strained interactions when picking up the children for the day or after a drunken outburst that leaves her in hysterics. Only then, at his uncontrollable worst, does Plover realize what Thalia has been asking for all along:

He could not understand how he had managed to fool himself all these months. It did not make any difference if Thalia had or did not have a boyfriend, or whether Plover stayed away and let her think things out, or if he forcefully took control and moved back in, daring her to move out. It would not matter if they saw doctors, lawyers, or counselors. It was over. He wanted to touch her or kiss her before he left, but he knew this was not the time. There would be time later, after they could become friends again. He had missed her friendship, he now realized, and he wanted it back.

Carpenter would never again be so nakedly honest about the battle of the sexes. Getting Off also marked the transition to his next major career stage. Carpenter made his first trip to Hollywood soon after Hard Rain Falling was published, and he would spend the next dozen years there in on-again/off-again fashion. His official output was rather sparse: one credited TV episode (for the second season of the western The High Chaparral), one teleplay (The Forty-Eight Hour Mile, a hard-boiled detective drama), and Payday, the 1973 film he wrote and produced that starred Rip Torn and brought back army pal Silverstein to compose the score. Payday (released on DVD in 2008) portrays the final three days of Maury Dann (Torn), a briefly successful country singer taking stock of his life’s downward spiral into drug addiction and doomed affairs. At the time, the movie was noticed only by a handful who admired its critical portrait of the country-music scene. Now it plays better, in light of how the “outlaw” movement of Tompall Glaser, Glen Campbell, and Johnny Cash has come and gone.

Despite commercial oblivion and personal frustration, the ripple effects of Hollywood upon Carpenter’s prose career were numerous, starting with two linked novellas, “Hollywood Heart” and “Hollywood Whore,” published in the 1969 collection The Murder of the Frogs. The novellas’ anchor is Max Meador, a movie-mogul composite of Louis B. Mayer, Darryl F. Zanuck, Harry Cohn, and other legendary studio bosses of a certain age. “I didn’t know what the rest of the world was like; thought everybody lived in this kind of misery and was afraid all their lives,” Meador muses in “Hollywood Heart.” The statement ironically mimics the very old-country ghetto Meador left behind for an increasingly corroded version of the American dream—one that exalts and slaps down his Jewish roots. Meador’s philosophy comes through in his rhetorical question—“When you got everything you ever wanted, why don’t you quit?”—and its answer: “Underneath it all was the fear. I could not stop. There was something inside me telling me, ‘You stop now, you end up back on the Lower East Side cutting throats for nickels.’ I knew it wasn’t true, but a person’s feelings are not subject to the control of the mind.” Because Meador cannot control his own feelings, he chooses to control everybody else’s.

The naive novelist of “Hollywood Whore” and the more cynical versions of the same character in Carpenter’s later Hollywood fictions all learned the same truth about screenwriting: it ranks almost as low as “any of the other technicians.” Carpenter himself believed that screenwriting was a form of technical writing, which has to be one of the most succinct descriptions of the profession. Whatever artistic illusions he had were long gone by the time he turned his attention to The True Life Story of Jody McKeegan (1975), an unusually structured quasi-memoir of a Hollywood success story that should never have been.

Carpenter’s early novels featured two–dimensional depictions of women and an unusual obsession with their menstrual periods—a career-long tic. (Just a few paragraphs into Getting Off, Jerry Plover, lying next to his sexually unresponsive wife, observes: “It was not her period. That had ended four or five days before.”) He found his footing with the 1969 story “One of Those Big City Girls,” depicting its heroine’s loneliness and pre-menopause with startling honestly and care, and progressed further with Getting Off’s Thalia. Jody McKeegan, however, is Carpenter’s finest female creation. At fifteen, Jody is all too cognizant of her weaknesses, especially in relation to her older sister Lindy. Jody is plain and pugnacious; Lindy is beautiful and sought-after. But instead of becoming an actress, Lindy follows a more typical trajectory of doomed love and unexpected pregnancy, leaving Jody with a growing sense of ambition. But just as in Hard Rain Falling, it takes tragedy for Jody to act on her ambition, with a lot of dues-paying along the way:

She had done worse, all right, lots worse. She had been a thief, a pimp, a blackmailer, a junkie, a liar and a cheat. She had pretended to love men she had despised. She had done it all and none of it had worked. Every time she got into a place where she might have had a chance, something inside her fired up and she ruined her chances. Always.

By rights, Jody McKeegan belongs in a David Goodis novel, her demons bringing her to the brink of oblivion time and time again. By thirty-five, she knows full well she’s out of chances, and her drinking and drugging aren’t helping. But it’s her fatalism that makes Jody appealing not just to the reader but to those in her orbit. Whereas a younger, more simpering starlet would have acted surprised at the casting couch—or, in the case of Maggie, let it both begin and end her career—Jody accepts it as her due and spins some kind of love for the producer in question, Harry Lexington. The mix of ambition and romance accomplishes what Jody wants: a supporting role in a weepie drama that might just be her big break.

With two thirds of the book over, Carpenter finally kicks Jody McKeegan into gear with his inside knowledge of the tedium and tension of a movie shoot. When it’s finally Jody’s turn to shine in a nude scene, not only does she establish her credentials as an actress, but she transforms outer plainness into inner beauty. “Harry would never be able to get the picture out of his mind: Jody in the twilight, her skin shining like bronze.” And then Carpenter twists things again, showing that success and despair are inexorably linked for Jody. One moment she’s triumphant; the next she’s inches away from shooting up heroin.

Having defined his Hollywood world, Carpenter brings Jody and Meador back for what may be his best book, A Couple of Comedians (1979). There is casual drug use and cynicism galore; Jody is every inch a star and Meador is a dinosaur still capable of imparting the valuable advice that you “don’t give the public new stories, give them new material”; but Carpenter spotlights a Martin and Lewis–esque comedy team, David Ogilvie and Jim Larson, and their struggle for normalcy amid the lunacy of a Los Angeles described as the “Golden Anus of the California Dream.” Larson is the wild one, prone to disappearances, blown deadlines, and missed opportunities. He “had no meanness in him,” but treats women cruelly and has little patience for anything outside of himself. Ogilvie, the narrator, has to be coaxed down from his mountain retreat to continue the act no matter how strong the pull to break it up once and for all. And just as those in fame’s outer orbit do, Ogilvie has his share of issues: supporting a friend clearly in the throes of manic depression, not getting the woman he wants, and not knowing what he really desires.

Carpenter repeatedly highlights the dichotomy of Larson and Ogilvie’s disintegrating bond. When Larson, late again, forces the camera upon him during a talk-show appearance, Ogilvie realizes the illusion underlying the camaraderie: “It was naked camera-stealing, but the people who wrote the letters saw it as an example of brotherly love.” Carpenter also uses Ogilvie to ironically delineate Hollywood class structure at the famed Schwab’s drugstore:

Beginners come here to somehow be absorbed into the mainstream, longtime hangers-on come to be with their friends and equals, stars and hits come to keep themselves honest and to remember, this is how it was and this is how it could be again. And a lot of people come here to look at the others, and a lot of assholes and dimwits show up to confuse the issue. I like Schwab’s.

The jokes are frequent and the satire has plenty of bite, but A Couple of Comedians works best when the humor is stripped away in favor of the heartfelt, as espoused by Ogilvie’s parting line to the reader: “This is love, my friends, and the hell with the rest.”

III.

Carpenter had one last Hollywood novel in him, 1981’s The Turnaround. It went deep into the nature of contracts, betrayals, and double-dealings—second nature to Tinseltown—but a combination of factors changed his work irrevocably as the decade wore on. He stopped getting regular work as a screenwriter, and lost his book contract with Dutton when both A Couple of Comedians and The Turnaround failed to meet sales expectations. Though Carpenter vacillated between bitterness and resignation about his professional fortunes, he was less equipped for the loss of one of his closest friends and fellow Enrico’s regular, Richard Brautigan.

Carpenter and Brautigan first encountered each other in the early 1960s, years before Brautigan hit it big with Trout Fishing in America, at a poker game where “everybody lost.” When asked to review the book upon its 1967 publication, Carpenter wrote: “In an age when any idiot with a typewriter and a dictionary can make a fortune writing muck, [Brautigan] has to try to be honest, and report life the way he sees it.” Ironically, Carpenter hadn’t actually read the book at the time he reviewed it. When he admitted as much to Brautigan, it didn’t matter: “Two pretty young Japanese women had seated themselves at a nearby table. I wasn’t there anymore.”

But Carpenter, despite his adopted role of confidante, had little sympathy for Brautigan’s women: “I thought they should have known going in that Richard was an extraordinary man and that his private life was bound to be pretty extraordinary, too. If they wanted the fun of running around with Brautigan, then they would have to put up with The Monster.”

Carpenter was unafraid to express his respect and admiration for Brautigan. “Know you’re not supposed to say this about the living (and Brautigan is definitely alive) and you’re certainly not supposed to say it about your friends (and Richard is my friend), but I’m sick and tired of hearing him described as over-the-hill or unimportant or silly by people whose sensibilities are, frankly, perhaps no better than my own,” Carpenter wrote in 1980 in the San Francisco Chronicle.

Four years later, Brautigan would lose his ongoing battle with depression, timed with the end of his turbulent two-year marriage to Akiko, a Japanese woman he wooed away from her husband. “The divorce broke him,” Carpenter believed, having watched Brautigan become an angry, ranting shell of his former self, who no longer had the charm or the wit to win himself back into his friends’ good graces. But the last words he spoke to Carpenter by phone were more poignant: “Darling, I love you. Good-bye.” They were also foreboding: Brautigan never ended a conversation by saying good-bye.

That good-bye didn’t break Don Carpenter, but it certainly did something to his writing voice. The ironic, documentary quality of the Hollywood novels gave way to a more subtle quality that stopped short of sentimentality. The younger Don Carpenter might never have crafted a novelette about a series of high-school classmates, as he did in The Class of ’49 (1985), or understood the seething tensions underlying a suburban community battling for supremacy over the perceived threat of the homeless and misunderstood, as in the underrated The Dispossessed (1986). The fifty-something Carpenter wrote as if he had less to prove and more to seek. He wrote about people who could have been his neighbors in Mill Valley, who might have ignored or even disdained the aging writer living in their midst. People like storekeeper Tim, looking for the “genotype of his dreams” in an immigrant clerk when a wife and children awaited at home; or Milos, waiting for the time when “there would come a new crazy man to the town square.” If Hollywood gave Carpenter a chance to explore the misunderstood against a larger-than-life canvas, the suburbs allowed him to narrow his focus in exploring similar territory.

Carpenter’s last published novel, From a Distant Place (1988), zooms in yet further upon a single family’s fission-like state. The Jeminovskis are both example and parody of the classic American family unit. Steven and Jackie divorced years ago, after young love dissolved into an alienated state of affairs and misunderstood feelings. Steven, a personal-injury lawyer, prefers pleasure to almost everything else; Jackie finds solace in drinking and empty one-night stands to replace the tedium of her overmortgaged, debt-ridden lifestyle. No wonder she can’t relate to her children. Her daughter, Deirdre, is so quick to crave stability that she marries at eighteen and hopes only to stay at the same telephone company for the rest of her life. Her son, Derek, is a lost soul whom Jackie “loved… but didn’t like much.”

Here again are more of Carpenter’s standard set motifs: poker-playing, devolution into a life of crime, obsession with menses, and the disconnect between perception and reality. But From a Distant Place also eerily foreshadows Carpenter’s ultimate end in the form of Jackie’s ruminations on suicide, casually dismissed early in the novel but hard to ignore after a particularly embarrassing series of alcohol-induced events:

She knew she was a goner. Drinking to kill a hangover was so obvious a sign that even she could not miss it. This would be the final phase. It occurred to her that she was drinking herself to death. The thought did not bother her nearly as much as it should have. Well, I’m going to die, she thought. There was no reason not to. She had lived her life and it had been a disappointment, but wasn’t everybody’s life a disappointment? The warmth was creeping through her whole body now, making her pleasantly thoughtful. She should have been frightened, but she wasn’t. It was a relief to know it was all over.

Having set up the expected response, Carpenter twists his narrative to kill off a supporting player in a surprising fashion. The world is random, he seems to say, so that those who are ready to die will not, and those wholly unprepared may pass on anyway. The benefit of hindsight adds even more logic to this plot switcheroo: Carpenter’s characters may be subject to random whim, but the author maintains control.

IV.

On a Thursday morning in 1995, the sixty-four-year-old Carpenter exercised his last bid for control in the form of a single shot to the temple. A complete manuscript, Fridays at Enrico’s, languished in the drawer after rejections from publishing houses large and small. A litany of illnesses, including diabetes, tuberculosis, and pneumonia, robbed him of his eyesight, kept him confined to his Mill Valley apartment, and left him unable to read or write for more than twenty minutes at a time. Friends and family members were shocked that Carpenter committed suicide—and by the news that he owned a gun—but for a man who resolved to be a writer at the age of sixteen, who knew no other livelihood, declining health must have destroyed his spirits.

The obituaries were respectful and kind, making note of Carpenter’s suicide but putting it in context with his health issues. “If anyone publishes Fridays at Enrico’s… it may remind the dwindling clan of serious readers that we have lost a shamefully neglected artist,” wrote Grover Sales in the Chronicle.

Carpenter remains neglected, though the republication of Hard Rain Falling will hopefully change that status. Should Carpentermania strike, there’s plenty more to investigate: not just the nine other books, but unpublished works (Enrico’s plus three novels written before Hard Rain Falling), unproduced screenplays, and even a book of children’s stories, all of which are housed in the permanent collection of UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library.

Fourteen years later, Enrico’s has gone through its own period of neglect and rebirth. After closing its doors in 2006, the restaurant reopened under new management the following year. The gut renovation makes it look more inviting, but if customer reviews are to be believed, something is missing. “Better service, yes, but it’s not the old Enrico’s,” writes one disappointed visitor. Perhaps the passing of its longtime owner left a bitter taste in the customer’s mouth, or the shift to more brightly lit decor. Or maybe it’s that Carpenter and the other hard-drinking literary ghosts that once haunted Enrico’s have faded from view.