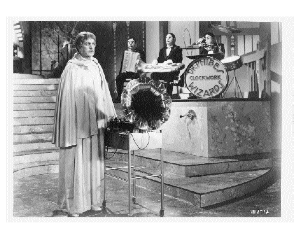

In 1971’s horror classic The Abominable Dr. Phibes, Vincent Price stars as a dead inventor who drinks champagne by pouring it into a speaker jack in the side of his neck. He looks like Captain Kangaroo with a hangover and is somewhat of a romantic, embalming his wife and preserving a sense of humor despite losing his face and voice box in a car crash. Phibes plays an orange Wurlitzer organ, cuts a fox-trot to his robot jazz trio (the Clockwork Wizards), and speaks through a golden art-deco Victrola plugged into his neck. “As you see and can hear,” he says, “I have used my knowledge of music and acoustics to re-create my voice.”

The Phibes socket appeared to be a modified fistula, the site of larynx extirpation for victims of throat cancer. It is a hole where a hole should never be, and Philip Morris would rather it not appear on television ads, much less the Marlboro Man’s gizzard.

Phibes’ DIY voice box was unique (if not insane) in that it was electronic and could still take a slug of Moët. The actual history of synthetic larynges claims inventions no less bizarre, many of which are German-made, with sources of inspiration ranging from balloon reeds and woodwinds to one patient who’d created his own fistula with a hot ice pick.

In 1870, Dr. V. Czerny was installing artificial larynges in canines, with dubious results (“The dog could yawn and make some noises”). In 1913, Dr. T. Gluck wrote of an underarm accordion bellows that plugged into the nasopharynx. More Phibesian would be Gluck’s motorized gramophone purse, which was wired to a denture plate (with tongue-flicked pitch control) and allowed patients to channel their favorite singer, a form of lip-synch by necessity.

Gluck’s experiments in “phonetik surgery” informed the research of Bonn University philologist Werner Meyer-Eppler, deemed by vacuum-tube nerds as one of the godfathers of electronic music, largely due to his postwar advocacy of a Bell Labs speech analyzer called the Vocoder. (Vocoder inventor Homer Dudley had already built a pneumatic reed larynx in the early 1920s.) As transistors grew more prominent, Meyer-Eppler developed an ElectroLarynx and published essays like “Observations During the Retarded Feedback of the Language.” In 1956, the U.S. government ordered AT&T to construct its own ElectroLarynx as well as research underwater acoustics for the military. By 1959, Bell Labs had unveiled what appeared to be a Right Guard can with a vibrating diaphragm. It had a pitch-shifter for inflection; though providing cordless communication, its persistent buzz seemed to indicate the presence of an invisible barber. According to Bell Labs, the ElectroLarynx was most effective when used over the phone.

In 1964, as chain-smoking...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in