A Thomasson, according to Japanese conceptual artist Genpei Akasegawa’s inaugural stab at defining it, sometime around 1982, is “a defunct and useless object attached to someone’s property and aesthetically maintained.” A doorknob in the middle of a wall, for instance, or the reinforced guardrails of a two-meter footbridge leading directly to a dead-end dirt road, or a stairway with a recently repaired banister that connects to a second-story window. It is something discovered in the urban landscape, generally, that serves no discernible structural or cultural purpose and whose continued existence can thus be understood only, in the context of modern capitalist logic, as art.

Understood is a heavily freighted word to use just there, but consider who was doing the understanding at the time: Akasegawa, an avant-gardist gadabout and writer with a penchant for pseudonyms, plus a bevy of his art students and eventually a small delegation of readers of his column in the photography magazine Shashin Jidai. They roved around Tokyo finding, inventorying, and commentating Thomassons with a curiosity that reads as perfectly genuine, if not quite serious; the cleanest distillation of the spirit in which they conducted their inquiries may in fact be the etymology of the word Thomasson, after an American baseball player who, during his tenure with the Yomiuri Giants, struck out so often he earned the nickname “the giant human fan.” “He had a fully formed body,” Akasegawa muses by way of explanation, “and yet served no purpose to the world.”

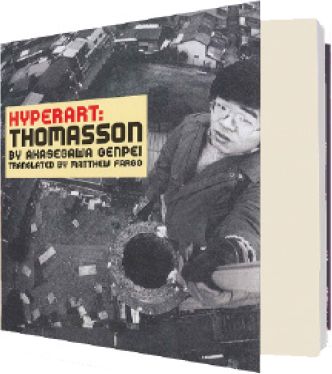

Hyperart: Thomasson is, and doesn’t purport to be much more than, a collection of Akasegawa’s columns, followed to what is presumably their actual historical termini. (It is also, for the record, a book filled with black-and-white images that are surpassingly lovely in themselves, equal parts psychogeographical whimsy and Richterian spectrality; while we’re at it, translator Matthew Fargo’s afterword alone is worth the cover price.) Shashin Jidai was more of a Playboy than an Aperture, and Akasegawa, avowedly eager to avoid highfalutin discourse, devotes much initial throat-clearing to distinguishing art, which is created by an artist, from hyperart, which is created by a combination of circumstances—entropy, desuetude, the “cruel pace” of the modern world—and merely recognized by an observer in the right place at the right time. He does not, however, deign to say that hyperart is easy to make, or, rather, to find; the would-be discoverer is freed of the strictures of aesthetic rhetoric, but an even more delicate form of sensitivity is required. “All Thomassons exist in a constant state of precariousness,” he writes, “wherein the slightest compositional change can render them mundane garbage, mundane decoration, mundane art.”

These are the certitudes of someone who is either irretrievably wrapped up in critical theory or making it up as he goes along, and Akasegawa merrily casts himself as the latter. He explicates hyperart in an amiably freewheeling and at times sensationalistic tone, often revising or contradicting earlier points as he proceeds; he is always curious, but sometimes he is methodical and sometimes flippant, sometimes irreverent and sometimes deceptively innocent—in his flights of interpretive fancy he is a child who has just learned what the pathetic fallacy is but still believes that buildings grow like trees. This is earnestly charming, even if it feels calculated to charm with its earnestness. “And so the eave became a Thomasson and went on protecting the likewise empty Thomasson beneath it, spending every passing day in mortal combat with the rain and dew,” he says of a protrusion near the Sanraku Hospital in Tokyo that was most likely once a mail drop. “And it did so in complete silence. Yes, that’s what lends it such beauty: the silence. It’s almost unbearable.”

It would have been enough for Hyperart: Thomasson just to go on pseudo-dramatizing Akasegawa’s pseudo-philosophy of vestigiality for a dozen or two columns, but another narrative, a darker one, begins to develop midway through. The weirdness in his chatter does not dissipate, but the winking quality does; the spectacle of existential gravity starts to feel less and less like spectacle. (“I’m pretty sure God exists,” he says of a photograph of a tree growing through a house, surrounded by stacks of logs and a mountain range in the background. “Wait—that’s totally irrelevant.”) As he moves through his fascination with the defunct, Akasegawa comes to seem interested less in the Thomassons themselves than in the purpose they no longer serve, or more precisely in the speculative conditions of the rupture between the two. At some point he tires of calling them Thomassons; they become instances, then schisms. For a time he seems to have discovered something but to know neither what it is nor how to charm his way out of it.

The column continues as before, but as Akasegawa’s focus shifts and the Thomassons gain a certain dignity, the hyperartist a certain tragic quality. Who is worse off, the book seems to reluctantly ask: the objects lingering in oblivion until someone gerrymanders them into art, or the still-living person preoccupied with things that no longer have a purpose? Is it sad that the Thomasson has been abandoned by the passage of time, or that the observer is jolted perpetually, unwillingly forward in it? The question, never posed, nonetheless becomes communicable. “Is it a Thomasson?” asks a reader, submitting documentation of a plywood-covered entryway. “Is it even beautiful?”

The gift of the book’s serial format is that we realize roughly in tandem with Akasegawa that hyperart is less about appropriating art and more about trying, and failing, to subvert the inexorability of time. When all the dots are connected, where is the end of the line, anyway? “In order to destroy one useless thing,” a different reader writes in, “you will be obliged to build yet another useless thing.” How long can you celebrate uselessness without wondering what around you will not finally become useless? How long can you celebrate the city as a living thing without realizing that it must also be a thing that dies? The city dies constantly, one might say, and Thomassons are its ghosts. “The ghost of architecture, the ghost of physical space,” Akasegawa explains, a few columns before the end:

It’s as if the spaces themselves were alive—or at least brought to life by people. People gave them breath. And so these living spaces also experience death, and their ghosts linger in the places they once lived, just waiting to jump out at you. Only people, after all, are capable of perceiving ghosts. And ghosts are probably the scariest things a person can perceive. But the scariness of a Thomasson doesn’t hit you all at once—it comes out in little bits, with a serene expression on its face.

Where Akasegawa has arrived here is as good a description of his project, of this book, as it is a statement about its subject. Whether this is by design is, as ever, inscrutable. A few lines later, he stares it down point-blank: “Maybe our fascination with Thomassons is really just our fascination with death.” Whereupon, without even so much as a paragraph break, he turns to the next exhibit, a fire escape that ends several feet off the ground.

—Daniel Levin Becker