In 1896 the Republican Party was in trouble. Its presidential candidate, William McKinley, was outmatched by his Democratic opponent, William Jennings Bryan, a legendary orator. Bryan would make eighteen thousand miles’ worth of whistle-stop speeches during the campaign. McKinley refused to travel. His wife, Ida, was a near-invalid suffering from epilepsy and depression. McKinley remained by her side, stolidly conducting his campaign from the porch of his Canton, Ohio, home. Out of necessity, the McKinley campaign became the first to make wide use of campaign buttons and memorabilia. For one of their giveaways, the Republicans went to the best, Sam Loyd.

“Mr. Loyd has a very ingenious brain, which is all the time thinking up peculiar things,” claimed the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Loyd was America’s foremost inventor of puzzles, then an important form of advertising. The McKinley campaign licensed the puzzle that Loyd considered to be his masterpiece: the “Get Off the Earth Puzzle Mystery.”

“It was developed under rather odd conditions,” as Loyd later recalled. Percy Williams, a vaudevillian-turned–real estate developer, had offered $250 for the best means of advertising the new resort community of Bergen Beach, near Canarsie in Brooklyn. “I said I would take a chance at it,” Loyd said, “and a few days later

I had worked out the Chinaman puzzle.”

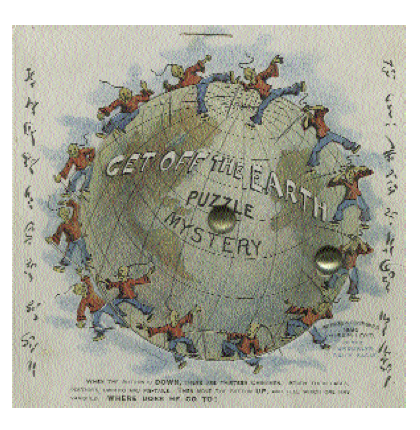

The puzzle was a cardboard disk affixed to a cardboard rectangle with a pivot. The disk represented a globe. Printed on and around the globe were pigtailed Chinese warriors fighting with swords. A button in a slot restricted the rotation of the disk. When the disk was in one position, there were thirteen warriors. When the disk was rotated to another position, there were only twelve warriors. How can a man, or even a mechanically reproduced picture of a man, disappear? “Study their faces, postures, swords and pig-tails,” advised the puzzle’s caption. “Can you tell which one has vanished? Where does he go?”

It was that simple—or maybe it wasn’t simple at all. American anti-Chinese prejudice was near its peak. Making the Chinese disappear was virtually the platform of Ireland-born Denis Kearney’s Workingman’s Party, which played off fears that Asian immigrants were taking jobs from whites. The name and premise of Loyd’s puzzle was disconcertingly evocative of the Workingman’s Party’s slogan, “The Chinese Must Go.”

The only explicit political message was that printed on the back of the puzzles that McKinley’s supporters distributed. It quoted from McKinley on the hotly contested issue of unlimited silver coinage. To most, the politicking must have been incidental. Loyd’s creation became a national sensation of a kind that is scarcely possible to conceive in our fragmented age of TiVo and iPods. Reportedly over ten million copies of “Get Off the Earth” were distributed. Loyd offered bicycles as prizes for the best explanations of the vanishing man, and people earnestly tried to win them. “Scientists have tried to solve it without success,” Loyd claimed. Among the puzzle’s addicts was New York mayor William Strong, who declared he would “solve the puzzle or break something.”

Loyd shrewdly refused to give any licensee exclusive rights. A&P markets gave copies of the puzzle to people who bought groceries, and newspapers used it to boost readership. Loyd fabricated a large version, operated by clockwork, as a window display. “The Disappearing Chinaman entertains and amuses everybody, and has not yet been exposed,” ran an ad in the Chicago Tribune. “The large reproduction working automatically is the greatest window attraction ever invented, and holds a crowd from morning till night.”

Loyd’s puzzle evidently helped put McKinley in the White House (one of his global adventures would be sending U.S. troops to China to suppress the Boxer Rebellion). The success of “Get Off the Earth” brought a flurry of pirated versions. Loyd’s 1896 patent on the puzzle seems to have deterred imitators less than the sheer difficulty of redrawing the artwork. Loyd, a skilled cartoonist himself, sketched the art and then had Anthony Fiala, cartoonist for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, do the final design. The unauthorized artists who redrew the puzzle found it almost impossible to deviate much from Loyd and Fiala’s model. In view of the fundamental importance of the artwork, Fiala—who later led an unsuccessful 1903–’05 attempt to reach the North Pole—deserves a share of the credit for the puzzle.

The following year Loyd issued a similar puzzle called “The Lost ‘Jap.’” Despite the epithet, the puzzle probably reflects the American popularity of Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado. Scattered among the men on the new puzzle were Japanese lanterns. When the globe was in one position, there were eight men and nine lanterns. Turning the globe produced nine men and eight lanterns.

“The Lost ‘Jap’” was a giveaway for Metropolitan Life Insurance agents. A prize of $100 in gold was offered for the best explanation; to collect, a contestant had to be a current policyholder. “This curious puzzle illustrates the uncertainty of life,” read the copy on the back. It segued into one of the strangest life-insurance pitches ever: “We see a little family circle of Japs suddenly broken up, and yet cannot tell beforehand which one is to go. We can only hope that the right one was insured when the miniature earthquake occurred. The moral is plain…”

Loyd’s final treatment of the theme came in 1909. It was the most technically accomplished of all, and perhaps the most offensive. The “Teddy and the Lion” puzzle has a rifle-toting Theodore Roosevelt surrounded by seven lions and seven spear-carrying African men done in the worst tradition of white folk’s “comic” blacks. The puzzle played off interest in Roosevelt’s post-presidential trip to Africa to bag taxidermy specimens for the Smithsonian. Turning the cardboard circle makes a man vanish and an eighth lion appear.

While many of the puzzles that Loyd popularized remain familiar today, “Get Off the Earth” and its successors have done just about that. There is little mystery there. The puzzles’ ethnic caricatures complicate any attempt to reproduce them. When Scientific American ran an illustration of “Teddy and the Lion” in the 1950s, the artwork was significantly redrawn. The black men were recast as boys, and the indications of ethnicity were all but obliterated.

Samuel Loyd was born in Philadelphia on January 31, 1841, the youngest of nine children. He said his ancestry included a Colonial governor of Pennsylvania. On his mother’s side, Loyd was related to painter John Singer Sargent (to whom he was compared, curiously enough: Loyd’s Times obituary reported that he was known as the “Sargent of problem composition” for his “impressions of wit and dry humor”). Loyd’s father was a successful real estate agent who moved the family to New York when Sam was three. Sam’s intentions of a career in civil engineering evaporated as he became smitten with chess. “For ten years, Loyd apparently did little except push chess pieces about on a chessboard,” wrote Martin Gardner, longtime “Mathematical Games” columnist for Scientific American. Loyd had scant success in tournaments, however. His peculiar talent was solely for composing chess problems.

There was money in that. Loyd wrote chess puzzle columns for Chess Monthly and other magazines. His trademark was dressing up problems in Munchausen-esque anecdotes. One of Loyd’s most celebrated chess problems was said to have occurred during the 1713 siege of the Turks, when Charles XII of Sweden was playing with one of his ministers at camp. Charles announced a checkmate in three moves. Moments later, a bullet shattered his white knight. Charles studied the board and declared that he did not need the knight after all; he had a mate in four moves. Another bullet took out a white pawn. Charles announced a mate in five.

Loyd broadened his output to include mathematical puzzles, rebuses, word games, and riddles (“What word is that to which, if you add a syllable, will make it shorter? Short.”) These filled puzzle columns that Loyd wrote for newspapers, his own Sam Loyd’s Puzzle Magazine, and such unlikely publications as the Woman’s Home Companion. Loyd offered prizes for difficult puzzles, receiving thousands of letters a day. The letters were sold for their addresses to early junk mailers. (“That isn’t a bad addition to one’s income,” Loyd confided.) From about 1870 on, Loyd spent much of his time inventing advertising puzzles, games, and souvenirs that he could print on his own lithographic press and sell in large numbers. Loyd was no less skilled at advertising himself.

“Loyd had a dark side,” Jerry Slocum told me. “Most of what he said was not true.” These words do not come lightly from Slocum, a retired aerospace engineer, author of books on the history of puzzles, and owner of a 30,000-piece private puzzle museum in the backyard of his Beverly Hills home. Loyd is one of the revered figures of the puzzle world. He was also a glib self-promoter who commingled fact and fiction. Loyd claimed to have invented the board game Parcheesi and the sliding-block puzzle with fifteen numbered tiles. Both claims added considerably to his reputation, though neither is true. Parcheesi is a traditional Indian game, and back issues of New York newspapers chronicle the 1870s craze for the sliding-block puzzle with no mention of Loyd.

Loyd’s fabrications went beyond résumé padding. In 1903 he published a history of the tangram, the Chinese puzzle of seven geometric tiles that can form a staggering variety of designs. Loyd said he based his account on the researches of a Professor Challenor and a set of four-thousand-year-old Chinese books, one copy of which was “printed in gold leaf upon parchment” and “found in Pekin by an English soldier who sold it for 300 pounds to a collector of Chinese antiquities.” Loyd’s British counterpart (and rival) Henry Dudeney repeated Loyd’s tangram history in his own writings. This piqued the interest of Oxford English Dictionary editor James Murray (of The Professor and the Madman fame). Murray contacted Chinese scholars and learned that they had never heard of Loyd’s Professor Challenor or his four-thousand-year-old books. Without quite calling Loyd a liar, Dudeney reported these findings in his own puzzle column.

Journalist Walter Richard Eaton wrote that Loyd’s downtown Manhattan office “would be dark even if the one window were washed, a cataclysm of which there seems no immediate prospect. There are two desks, a typewriter, and a printing press in it, and countless shelves loaded with papers, pictures, magazines, stereotype plates, and one thousand other things which have spilled out upon the floor and risen like strange, dirty snowdrifts breast high in the corners.”

Loyd was described as a tall, quiet man, skilled in wood engraving, mimicry, ventriloquism, and the rapid cutting of silhouettes. He did an informal ventriloquism act with his son, also named Sam Loyd, in which the son accurately lip-synched to his father’s thrown voice. This was oddly prophetic. After the elder Loyd died at his Brooklyn home on April 10, 1911, the younger Loyd dropped the “Junior” and assumed his father’s professional identity. “But the son, who died in 1934, did not possess the father’s inventiveness,” wrote Martin Gardner; “his books are little more than hastily assembled compilations of his father’s work.”

*

Despite Loyd’s taste for aggrandizement, he had relatively little to say about “Get Off the Earth,” which Gardner, Slocum, and other puzzle connoisseurs have rated Loyd’s finest invention, if not the most ingenious mechanical puzzle ever created. Here too Loyd probably drew on an uncredited precedent. A “Magical Egg Puzzle,” copyrighted in 1880 by R. March & Co., employed the same principle, albeit less elegantly. The Magical Egg card had to be cut into four rectangular pieces and rearranged by hand to work the vanish. As Slocum points out, it took a fantastic leap of imagination for Loyd to realize that the concept could be applied to human figures and a circular format. This was Loyd’s authentic innovation.

Thousands of explanations for “Get Off the Earth” were submitted to Loyd’s puzzle column. Some writers carefully numbered the figures and singled out a specific man as the one who vanishes. A few offered implausibly precise destinations for the missing man. (St. Petersburg, Russia, according to one contestant who looked very closely at the printed globe.) One entry was in verse, several took swipes at Chinese immigration, and one writer felt that the puzzle had something to do with his conviction that all Chinese men look alike. The winning entries were published in Loyd’s January 3, 1897, Brooklyn Daily Eagle column. They were accompanied by Loyd’s own explanation, a peevish, long-winded rant that withholds as much as it reveals.

Martin Gardner supplied the best concise explanation of the vanish effect I have seen. Of “Teddy and the Lion” he wrote: “[I]t is meaningless to ask which lion has vanished or which hunter has newly appeared. All the lions and hunters vanish when the parts are rearranged—to form a new set of eight lions, each 1⁄8 smaller than before, and six hunters, each 1⁄6 larger than before.”

If this is still not clear, the diagram on the preceding page will explain better than words.

In (a) there are four rectangles. Cut on the dotted line and slide the top portion to the right to form (b). Now there are only three rectangles—each proportionately larger than before.

The effect is facile with rectangles—save perhaps in the case described in William Hooper’s Rational Recreations (1774). Hooper told how it was possible for grifters to slice apart nine British banknotes and rejoin the pieces into ten bills, each a little smaller. The more bills used, the less evident the shrinkage. Even today, the serial number on U.S. currency is repeated, at upper left and lower right, in part to foil such mischief.

Loyd’s puzzles bend the dotted line above into a full circle. In place of rectangles arrayed on a diagonal, the puzzles use cartoon men arranged in a spiral. The spiral layout allows the dial’s circumference to split each man differently. The artist must draw each figure so that it can grow or shrink gracefully. Turning the puzzle to the “missing man” position pairs each of the dial’s partial figures with a somewhat larger outer portion. “Each… man has absorbed a small portion of the missing one,” Loyd’s patent explains, “which is so evenly distributed as to be almost imperceptible.”

In truth there are no whole men, only fragments, as contest winner W. H. Fitch asserted. “Get Off the Earth” has twenty-four fragments that can be arranged to form twelve or thirteen figures. Loyd and Fiala make this simple premise mystifying with several artistic tricks, some of which Loyd enumerated in his explanation. The legs of two dueling figures overlap, hiding the fact that neither has a complete leg. The indifferent quality of the color printing is often helpful. The billowing sleeve of one warrior’s red shirt becomes a foreshortened arm and half the face of another figure. Though the resulting half-face is red, the eye forgives it, putting it down to sloppy printing. It is said that great artists make the most of a medium’s limitations. By that criterion, Loyd and Fiala are masters of the misregistered lithograph.

Even the unpleasant depictions of the Other fit into Loyd’s design. “The grotesque figures of the Chinamen were absolutely necessary,” Loyd insisted. The figures’ growth and shrinkage are less conspicuous with caricatures of exaggerated and uncertain proportions. Loyd recognized that the then-omnipresent “grotesque” depictions of Asians and Africans were an effective camouflage.

The Metropolitan Life puzzle added a second spiral, running in the opposite sense, for the Japanese lanterns. A turn that annihilates one man simultaneously adds one lantern. “Teddy and the Lion” put lions on the second spiral. In this puzzle particularly, Loyd makes deft use of ambiguity and overlap.

Loyd’s creation has had a long and troubled afterlife. There have been scores of attempts to produce politically correct versions of the puzzle (with leprechauns, devils, pirates, ninja warriors, etc.). McDonald’s once gave away a version with vanishing hamburgers, Siegfried and Roy’s website has one with white tigers, and a soft-porn version with nude blond women exists. Most of the newer puzzles revert to the less demanding rectangular format. The artwork often has a hasty, halfhearted feel. No such puzzle since Loyd’s has managed to create so much as a blip on the pop-culture radar.

Borges wrote that Kafka created his own predecessors. You find echoes of Loyd’s vanish puzzles in Heraclitus, with his claim that it is impossible for a man to step into the same river twice. It is no longer the same man or the same river. Loyd too trades on the illusion of wholeness in a world of flux. “Which man has vanished?” and “Where did he go?” are red herrings of a particularly diabolical sort. The only proper response is the words attributed to Gertrude Stein: “There ain’t no answer. There ain’t gonna be any answer. There never has been an answer. That’s the answer.” As Loyd well knew, we go on asking the question still.