Harmony Holiday’s father was the successful soul singer Jimmy Holiday, who died in 1987, when she was five. Her shortest poem, “The Soonest People,” becomes his almost-straightforward memorial: “My father was Jimmy, dad / was weeping so frankly it came like gazing had.” Other poems bear musical titles: “Duets,” “Certain Ballads,” “Nine Key Chord,” “Errand boy for rhythm,” “Dixie is a two beat thing / 11:11.” You could try to read this first book as a long, weird elegy to the father she never much knew—in fact, its musical elements almost tempt us to read it that way—but then it speeds away, into other subjects, other riffs, other lines. Its fast, trippy poems, most of them in prose, are sometimes kinds of elegies, but always kinds of escapes; kinds of homages, but also ways to leave home.

Holiday’s travels get help from symbols of black history, which she treats as one would a wardrobe: “I am proud of the things I favor, so sore from them. African’s Heals, real move, malarkey, copper, lucre off proof, burr green and bergamot, polyester until I look like a jazz trumpeter’s best wife.” That poem is called “A Child’s F.Y.I.,” and Holiday seems to imagine herself playing dress-up; in fact, every poem, not just her poetry (so she implies, and she’s right), might work like such a game, an initially ill-fitting, always-temporary costume, made of clothes or of words, that delights and liberates the figure underneath.

Almost every agitated emotion, every kind of intense experience, seems to find a place in Holiday’s pages. It would be wrong to ignore the sadness and the frustration, but it would be even more wrong to ignore the explosive verve, the insistence on happiness, on something to run toward: “we’re lucky we ate that dirt in Iowa, we’re lucky haiku unbuckles, lucky shuttling’s the feeling and not shut, we’re lucky the lady means to be a healer, we’re lucky for trots for word for word, and this field’s higher weather for earth or not.”

If I can make language do that, the poems seem justly to exclaim, I can make it do almost anything—anything, perhaps, except slow down. Holiday teaches dance as well as writing; sometimes her poems seem to seek the kinetic immediacy, the physical meaning, that escapes from language. Some poems are also frankly sexy: “I think of you again and feel assent and infinity and the sweet what-for of a vertical jump on my Bribing Trampoline, consecutive knees hexagon around a compass which points to none of us is eager enough.”

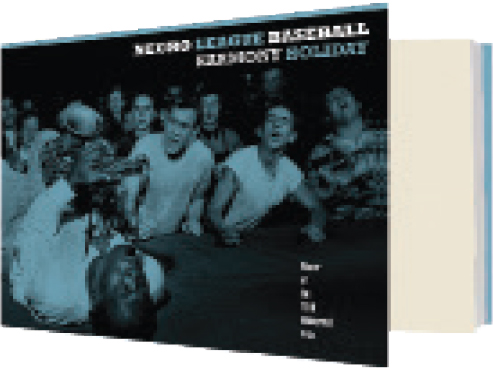

Negro League Baseball is not the only book published by Fence with extra-wide, extra-short pages, but here the unusual format seems appropriate, since it fits the book’s fast-forward motion: phrases open up like fireworks, wild dreams, the unfolding jams of some funk, some free jazz, escaping from old measure’s rules. Holiday’s lines are not, or at least not obviously, finely calibrated or well controlled; if you read them in the wrong mood, they can seem profusely disheveled or uncomfortably close to automatic writing. There are things she can’t do, or doesn’t want to try to do. But that is just to say that, like all poets, she has the defects of her virtues: excitement, oddity, a connection to black musical tradition, a willingness to travel far from prose sense and far from origins, and a determination to move. “The beautiful things have grown perverse in their transfer from hang to glimmer,” she says, and it’s not a complaint but a recommendation: “I pick the kind of power sullen never nullified by how-come-it’s-yours.”

—Stephen Burt