Have I seen Ayla Reynolds?

Everywhere I go in my hometown, since mid-December, I have been asked this question. Every time I step into a convenience store, every time I open the door to the gym, every time I walk into my favorite restaurant for lunch, every time I go to my favorite bar for a drink, there’s a picture of Ayla, diminutive tot with a head of white-blond corn silk, smiling out of a photograph from a happier time not all that long ago. And above that photograph, or below it, the ubiquitous question: Have I seen her?

The answer has been, and remains: no. I have not seen her. I, like many others, hope that I will. But instinct and common sense tell me I will not. Instinct and common sense tell me that, since the day she was reported missing, since the day the first search parties were organized and people started lighting candles and holding group prayers and vigils and debating on Facebook and in the local paper’s comments section about what happened to her, where she is, whether either of her parents was fit to raise her, whether state agencies responsible for children’s welfare did their job, since the day our voyeuristic proxy, the media, descended and Nancy Grace primped her hair and punched the clock and counted down three, two, one, and began holding forth in her patent-pending shrill tones, the whole circus of increasingly delusional hope and co-opted grief has been completely, grotesquely moot, because since that day, Ayla Reynolds has in fact been dead, suspended at the bottom of a river, maybe, or buried shallow under a stand of white pines, or somewhere in the most recent geologic layers of a landfill, dead, instinct and common sense tell me, never to be seen again, never to smile again as she does in the flyers posted at the gym and the restaurant and the corner store, the flyers asking me over and over again have you seen her?

*

The whole circus of increasingly delusional hope and co-opted grief began like this:

December 17, 2011, 8:51 a.m.: Justin DiPietro, Ayla Reynolds’s father, reports the twenty-month-old missing from his Waterville, Maine, home. Police searches commence, eventually bringing in canine units, the FBI, and civilian volunteers. The central Maine Morning Sentinel gives the details as they’re known at the time: Ayla’s father and mother do not live together. The child’s arm was broken, and she wore a sling. Her father says she was last seen in bed around ten o’clock the previous evening.

December 17, immediately upon reading the Sentinel article: my bullshit meter starts to scream. DiPietro is expecting police to believe that he put a toddler with a broken arm to bed and didn’t check on her for nearly eleven hours? And by the way, how did the girl break her arm in the first place?

*

So: have you seen Ayla Reynolds?

Likely not, I realize, and more’s the pity. Here’s a different question, then, one better suited to the purposes of this essay, and one more likely to be answered in the affirmative: do you know who Ayla Reynolds is? Have you seen any of the innumerable reports on her disappearance? Are you as hungry as the rest of America is for stories about missing children? Do you watch the Today show, or Good Morning America, or Nancy Grace?

I don’t know Ayla Reynolds, but I know who she is. It’s possible, maybe even probable, that in the last couple of years I saw her somewhere around this town (it would have to have been in the last couple of years, because as of this writing she would be only twenty-three months old). It’s a small place and we both live(d) in it. But even if I did see Ayla somewhere along the line, she wouldn’t have made much of an impression on me, most likely, because she would have been just a baby in a stroller, and this town is full of babies in strollers, and especially full of babies in strollers being pushed around by young, disheveled, directionless poor people, which is a fair way to describe Ayla’s parents, if one is being honest.

*

Some of the only childhood memories I trust are of going to the corner store to buy the clichéd essentials: a gallon of milk, a loaf of fortified white bread. Part of the reason I remember these hunt-and-gather assignments my mother sent me on is because I got to carry a book of coupons that showed up in the mail once a month and represented what seemed like unlimited buying power. These coupons were the early-’80s equivalent of loaves and fishes (a parable I was intimately acquainted with by then): they produced so much from so little. And they were pretty, and colorful, much more handsome and aesthetically pleasing than cash. Years later, when I went to Europe in my early twenties, the currency rainbow of the Old World would remind me, over and over, of nothing so much as the food-stamp booklets of my upbringing.

*

Recently, in the town where I grew up, in the town where Ayla Reynolds went missing and likely was murdered, I stood in line at the convenience store and waited for a couple of women in their early twenties to complete two transactions. I smoldered as they separated their items into discrete piles, because I knew what was going on. They were using government funds, in the form of a Maine EBT (Electronic Benefit Transfer) card, to buy Lay’s barbecue potato chips and Slim Jims, while simultaneously using cash from an unknown source to buy loose tobacco and filtered cigarette papers. I cared less about them wasting my money than wasting my time—either way, though, I was hair-trigger impatient.

But on the point of them wasting my money, let’s consider (as I must every time I go into this store after 9 p.m., because at that hour, and throughout the night, the clientele consists almost entirely of people using EBT cards) that beyond the fact of these young women buying tobacco when they presumably can’t afford to eat, they’re allowed to spend government money on junk food: potato chips and Slim Jims, in this case, but the same scenario plays out countless times in this very store with every imaginable item on the empty-calorie spectrum, from gummy worms to Sno Balls to TGI Friday’s potato skins.

It’s safe to assume, by the way—and really, trust me on this—that these young women also had, between them, at least two or three kids waiting at home, kids whom they presumably could not afford to feed, as they stood at the checkout counter wasting both my money and my time.

*

I like to tell myself that mine was a different kind of family, growing up. Sure, we were on “assistance” when I was young, but my parents worked and worked. I tell this story to other people, too, whenever the subject of welfare comes up, and I attempt a measured criticism of the system and those who benefit from it. Mentioning that my family received WIC and food stamps serves to legitimize my critical stance, or so goes the reasoning in my head. Listen, I say, I snacked on government cheese, gleefully cutting thick hunks of yellow American cheese from a five-pound block in a cardboard sleeve marked usda, but my father worked endlessly, sometimes holding as many as three jobs at a time. Sure, I ate free breakfast and hot lunch at school, but my mother pulled down a paycheck serving those meals to me and my classmates in the school cafeteria. We weren’t like these layabouts I see buying potato chips and Slim Jims and tobacco and malt liquor.

But the truth is, one could argue that we were like them, in a manner. My parents smoked, and they smoked the whole time we received government assistance. Presumably, both my mother and my father went into stores and separated their items into two discrete piles, one paid for with food stamps, the other with cash. It’s likely, though I don’t remember it, that I did this myself, on my hunt-and-gather trips to the corner store. I’m sure there was more than one occasion when my mother handed me the food-stamp booklet and a five-dollar bill and told me to buy a loaf of bread, a gallon of milk, and a pack of Winston Light 100s. Had to have happened.

*

And yes, believe it or not, there was a time when the cashier at the corner store would sell a six-year-old a pack of cigarettes, as long as he said they were for his mother. Which they were. Until they weren’t.

*

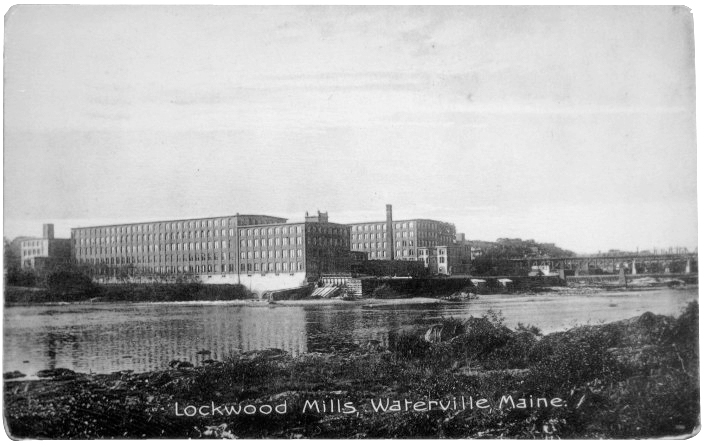

What does this have to do with Ayla Reynolds, you wonder? I’m wondering the same thing, to be honest. The connection, if there is one, seems to be bound up in the fact that, in the town where I grew up and still live, things have only gotten worse since I was a kid. Back then there existed real and viable industry here, represented by the Hathaway shirt company and the brooding brick monolith of the Scott Paper mill, just on the other side of the river in Winslow. Pretty much everyone had family who worked at one of these two places. My mother did a stint at Hathaway that I am too young to remember. My girlfriend’s mother spent a career there, first doing piecework, then on salary, after she and the other women got too good at their jobs and started making too much money.

Then, in 1997, the Scott mill, under the auspices of Kimberly-Clark, was shuttered. Hathaway followed, in 2002, after futile last-ditch efforts by financiers to keep it open. Since then, you know, things have changed. Or maybe I should say things became the way they’ve always been, only more so. These days there’s a stock line I use to explain the situation here: the local economy is now predicated on selling pizzas to one another.

*

It’s likely, of course, that it’s not as simple as I make it out. In talking with my girlfriend about her mother’s career at Hathaway, she mentioned that her mother hated the place, and that her father told her mother that if she hated it so much, she should quite simply do something else. “Which she could have,” my girlfriend said. “There were other jobs.”

She’s right, of course. But I countered by saying, “Sure, there were other jobs. But there were other jobs because Scott Paper and Hathaway existed in the first place.”

*

In any event, I bring all this up, I guess, because I want to convince you that Ayla Reynolds’s parents were, and probably still are, on welfare of some kind. I have no evidence of this, of course. But I don’t need any, and here’s why: I just know. I know, in the same way that I know when I’m standing in line behind someone at the store after 9 p.m. that they’re going to whip out a Maine EBT card. I know because when one is neck-deep in state services, and when that entanglement in state services is a legacy—Ayla’s grandmother has claimed the Maine Department of Health and Human Services has a bias against her family, which bias (real or imagined) one presumes could result only from long and intimate contact with said family—chances are very good that one receives welfare benefits. (To put it more plainly: where there’s DHHS, there’s almost certainly WIC and food stamps, and probably housing assistance to boot.) I know because I recognize these people on sight, and I recognize them because I grew up among them, am related to them, am, in fact, one of them myself, erstwhile though I may be.

*

Actually, now that I think about it, I’m not trying to convince you that Ayla Reynolds’s family, or some portion thereof, is on welfare. What I’m trying to do is tell you that this is the assumption I’m working from, and that I believe it is almost as safe an assumption as the one I make every day about the sun coming up in the morning.

And also that this is the assumption that many, many other people are making about Ayla Reynolds’s family.

*

By now many people are convinced that Ayla’s father, Justin DiPietro, is responsible for her disappearance. They cite the fact that Ayla was in his care, that weeks before vanishing she had suffered a broken arm under his watch, that the eleven hours that lapsed between when he claims to have put her to bed and when he called the police the next morning strain credulity, and, even if true, give the impression that he was neither a very caring nor a very competent father. And then there is the fact that DiPietro’s mother, Phoebe, gave an interview backing up DiPietro’s account of the events in the house that night, then later admitted she wasn’t there and thus could not possibly know, any more than we can, what went down.

So naturally there’s been a lot of speculation and finger-pointing. He did it, people think. Or at least he had something to do with it. Ayla’s mother, Trista Reynolds, believes this. Many in the community believe this. They want to know what happened. They’re demanding to know. They’re demanding satisfaction, demanding Justice for Ayla.

*

I sometimes wonder if all the people clamoring for satisfaction and justice are maybe missing the point, though. Because to my mind, although I believe it’s important to discover how Ayla disappeared, and at whose hands, it’s at least equally important to pick apart the circumstances leading up to her disappearance, to stop pointing fingers at Justin DiPietro and his family long enough to take a look in the mirror and ask ourselves why we’re interested in Ayla only now that she’s gone and likely dead, now that we’ve had the perverse excitement of seeing our little town on CNN and The Morning Show.

Disappearance and mystery being a lot more sexy, if we’re honest, than the sort of workaday neglect and abuse that sometimes result in a toddler ending up, for instance, with a broken arm. Or, for another instance, a toddler being left in a crib unattended and unchecked-on for eleven hours, while her father and his friends hit the corner store to buy Slim Jims and potato chips with an EBT card, and liquor and tobacco with cash.

*

Trista Reynolds, Ayla’s mother, said in an interview, “I don’t want to know if she had to suffer or if she was in pain. I don’t want to know how she felt. That’s not something a parent or a mother should have to feel.”

On reading this, it struck me as remarkable: in essence, the woman was saying she did not want to feel the emotional weight of whatever horrible things her twenty-month-old daughter had to go through. Saying that she should not have to feel those things, despite the fact that her daughter certainly did.

It’s a sentiment I normally would agree with, on principle. Who would want to ruminate on the horrible fate of any loved one, let alone a daughter? But I can’t get past the utter selfishness of it. The grotesque inward focus, the childishness of refusing to accept the inevitable consequence of bearing a child: that you will, in one way or another, experience pain, even if the kid never goes missing or turns up dead.

*

And let’s not forget that the only truly innocent party here, the only one who indisputably should not have had to feel these things, is Ayla herself. If her mother did not want to feel these things, one could argue that she should not have had a child. Or that she should have questioned the wisdom of having a child with a man whom she did not love, or with whom she did not plan at least to try to raise that child. Or that she should not have let herself get so deep into drugs and alcohol that state agencies took her daughter away and left her in the care of this man, as she has repeatedly claimed they did. But no. Despite the fact that Trista Reynolds chose, as an adult, to set up the circumstances under which Ayla came to be where she was on the night she disappeared, Trista believes that she should not have to feel these emotions that are the direct and somewhat predictable consequence of her own decisions.

*

Trista Reynolds has speculated publicly about bringing suit against the Maine Department of Health and Human Services, and blames it for her daughter’s disappearance.

“DHHS just didn’t do their job,” Reynolds said, apparently giving no thought to the fact that she didn’t do hers, either, and that this was arguably the greater of the two failings.

*

Trista Reynolds has another child, a boy named Raymond Fortier. Raymond was nine months old at the time of Ayla’s disappearance. Only eleven months’ difference in the two children’s ages, yet they have different fathers and different last names.

*

I have two half siblings of my own. We were raised together and have the same last name and didn’t know we were only half siblings until my older brother was almost out of high school. Before my father came on the scene, my mother had married very young—at sixteen, or thereabouts—to a man who by all accounts was an abusive drunk, just like her father, my grandfather, had been. We seek that which we know, I guess, and tend to repeat the examples that have been imprinted on our cerebral cortexes at a young age. In any event, my mother had two children with this man in fairly quick succession, children whom, a couple of years later, my father would adopt, give his name, and raise as his own. Then they had me.

*

In 1990, when I was a freshman in high school, this town had 17,538 residents. By 2010, with the Hathaway shirt company and Scott Paper both gone, that number had dropped to 15,719. Doesn’t seem like much of a difference, until you consider that this is an 10.6 percent slide during a period when the U.S. population as a whole grew by nearly 19 percent. In that same time, the median income here, in terms of real dollars, fell precipitously. The work force shrank, which you might fairly assume was tied to the dip in population, except that the unemployment rate, as a percentage of population, went up. By the time Ayla Reynolds vanished, it had been nearly a decade since we made anything here—other than the pizzas, of course.

*

But you know what Twain said: lies, damned lies, and statistics. So how about this: when I was a kid, each year this city paid to decorate downtown spectacularly for Christmas, with trees glimmering and an amazing tunnel of white lights strung in a canopy from lamppost to lamppost the entire length of Main Street. In contrast, just a couple of years ago, desperate to save a few bucks, the city turned off some of the downtown streetlamps. More recently, there has been momentum behind efforts to consolidate emergency services and school districts because of budget shortfalls. Of course this is happening everywhere now because of the recession, but, understand, we barely felt the recession here. We stared at our television screens and wondered what everyone was making such a big deal about, what everyone was so frightened and angered by, what, exactly, had changed. We’ve been recessed forever. It just took a while for the rest of you to catch up. For us, this is business as usual—business as it has been, such as it has been, for quite some time now.

*

Speaking of which, Forbes has listed Maine as the worst state in the union for businesses two years running. Number fifty out of fifty.

*

A couple of days ago I was eating pizza and watching preseason baseball at a local pub—to give you an idea of just how small this town is, people refer to the place as “the Pub” and leave it at that—and my younger brother came in and wanted to chat. He told me that he’d “finally” gotten “my disability,” and so had decided to buy a house. He’s in his early thirties.

Note the language: “my” disability.

He’d gotten his slice of the American pie, or what passes for it for so many around here. “Finally.”

*

Though they’ve been extraordinarily tight-lipped through all this, police did say, a few months after Ayla disappeared, that they believed the DiPietro family was withholding information from investigators.

Meanwhile, the Waterville chief of police was quoted as saying the search for Ayla Reynolds could top half a million dollars in costs, in a city that recently turned off streetlights to save money.

Also: Lance DiPietro, brother of Justin and uncle of Ayla Reynolds, was arrested in early February for an assault that resulted from a difference of opinion regarding what had happened to his niece. At his recent arraignment, Lance DiPietro pleaded not guilty, asking for, and receiving, representation by a public defender. As is his right.

It is, of course, my civic responsibility to pay for the search for his niece, and for his fair and impartial trial, and to provide him with a court-appointed lawyer if he cannot afford his own. This is a responsibility I take seriously, because I believe in the social contract, and I believe in due process.

Nevertheless.

*

And this is where writing about all this gets a little weird, where I start to experience something more than the low-level dissonance that results from seeing versions of my own family in the DiPietros and Reynoldses: because this town being as small as it is, it was probably impossible that I wouldn’t know at least one of the major players in the Ayla drama, and I actually know Lance DiPietro. I used to work with him, back about six or seven years ago. We did time together in the kitchen of a Ruby Tuesday, and we got along. He was a good kid, if a bit goofy, and smarter than he had probably ever been given credit for. Some days he did his work, and some days he needed a bit of prodding. But his heart, as they say, was in the right place, even if he had a habit of tripping over his dick more often than was good for him.

And I guess this is where I end up feeling the same as so many other people do who are ancillary to the disappearance of Ayla Reynolds, yet have, or feel they have, something at stake here, and thus take sides and demonize the other and stick up for the people in their camp regardless of any revelations that might come along to indicate that the people in their camp kind of suck shit. Because the thing is, some people think that Lance DiPietro knows what happened to his niece, despite his public calls for Ayla to be returned to the family, despite his organizing vigils and mourning in public. I’m not sure they go so far as to say, or think, that he actually had something to do with her disappearance. But they believe his loyalty to his brother is such that he’s covering for him, impeding the investigation, standing in the way of Justice for Ayla.

I don’t want to believe this, despite all the circumstances that point to the possibility. I don’t want to believe this, because I know Lance, and because I like him.

But if I’m not convinced that Lance is withholding information, I’m not convinced he isn’t, either. And if he is, then he, along with the rest of his family, have not only spirited away and possibly caused/facilitated the death of a twenty-month-old child, but they also, through their refusal to own up to what’s happened, continue to cost a community and a state hundreds of thousands of dollars, and to deny many decent people whose money fills municipal and state coffers the emotional satisfaction of seeing justice done.

*

Not to mention that the longer this goes on, the more press it gets, and every time Nancy Grace fires up the Harley-Davidson of her indignation and asks the tough questions, every time George Stephanopoulos checks back to see what developments have occurred in the case—every time anyone from the national media says those magic words reporting from Waterville, Maine—it gives insult to a small town already reeling from twenty years’ worth of injury.

Some of us here, a handful, I’d guess, are embarrassed. But not nearly enough of us. Mostly we’re just pretending that lighting candles makes all the difference in the world, that vigils are meaningful support, that prayers change facts. We’re pretending that symbolism equals action, that hanging flyers and tying ribbons can resurrect the dead and absolve us.

*

The pattern established itself early on, just after Ayla disappeared: Justin DiPietro talked to no one but investigators, and only issued public statements through the police department; Trista Reynolds, on the other hand, talked at length to anyone who’d point a camera at her.

Nothing unusual about this last, I suppose. Parents of missing children often go on television to plead for their return; I know the drill as well as any American. But the devil’s in the details, and in this instance the devil is in the way Trista Reynolds comports herself, there with Matt Lauer on the overstuffed furniture of the Today show studio, in the way she smiles too readily, the way she heaves heavy, unconvincing sighs where indicated, the way she seems at times to be reading from a script. Watching her, I don’t feel a single moment of genuineness, not one moment when whatever anxiety she has about appearing on national television gives way to real grief and fear over her daughter’s disappearance. Given this, when Matt Lauer says he knows how hard this must be for her, it drops almost like a punch line. Which is not to say that Trista doesn’t care—it’s simply to say that, not surprisingly, she doesn’t appear to have the character necessary to be a good mother. It’s pretty obvious that at this moment her primary concern is not her daughter’s whereabouts or well-being, but how she herself is coming across in front of the cameras. She’s enjoying the fact of an audience. She’s the star—after all, and all of a sudden—of her own drama, previously writ small and dirty, now being broadcast into homes all over the country. And as Trista Reynolds knows as well as anyone: here in the Nation of the Blameless Self, if you’re not grieving on TV, then by god you’re not really grieving.

*

Listen to Trista Reynolds, talking about her daughter Ayla: “I used to tell her she was going to be Mommy’s star, but this isn’t how I wanted her to become a star.”

*

To my knowledge, the last time Waterville blipped on-to the radar screen of the national media was back in 2002, on the first anniversary of 9/11. My father happened to be one of the people involved. He was on duty at the fire station. He and his shiftmates were preparing to hold a brief ceremony in dress uniform to commemorate the anniversary of the attacks, when a car came screaming up outside the station’s truck bays, a frantic man at the wheel. The man’s very pregnant wife lay across the backseat, about to give birth. There wasn’t much time—just enough, really, for my father and another firefighter to go to the woman and basically catch the football. Here’s the pertinent detail, though, the coincidence that caught the attention of the networks and People magazine and others: when the baby was born, someone asked what time it was, and the answer came: 8:46 a.m., one year to the minute since American Airlines flight 11 had barreled into the north tower of the World Trade Center.

Flash forward to a few days later: my father and a handful of other Waterville firefighters sitting for an interview with the Today show via satellite. Again, it didn’t last long, fluff pieces and the time constraints of network television being what they are. But while it did last, my father, much like Trista Reynolds, looked acutely uncomfortable sitting there with the cameras glaring at him. Unlike Trista Reynolds, though, he didn’t say a goddamn word, just let others answer the questions and waited for it to be over.

I would guess that they were both, during their respective interviews, Trista and my father, dying for a cigarette.

*

What other parallels could I draw here between the people I love and the Reynoldses and DiPietros?

Well, for one thing, if not for a facility with language that I didn’t earn and don’t deserve (any more than I earned an allergy to cats, for example, or deserve the brown eyes I was born with), I would almost certainly still be slinging slop with Lance DiPietro—he’s recently been doing time in the cramped kitchen of “the Pub,” and has made more than a handful of pizzas for me over the last few years, while I drank cheap domestic beer and watched baseball and wondered, at leisure, how long it would be before my food came out.

If not for some moment of desperation or strength or frustration unknown to me, my mother might have stayed married to the abusive drunk. Or she might have left him and taken up with another just like him. Maybe she would have gotten split custody of my two half siblings. Maybe she would have let herself get in a little too deep with alcohol, and maybe my two half siblings would have been placed by DHHS with their father, the abusive drunk, and maybe one or both of them would have turned up missing one day, never to be seen again.

If not for the constant cash infusion proffered by Scott Paper and the Hathaway shirt company during the ’70s and ’80s, maybe my parents never make enough money, no matter how hard they work, to get off “assistance.” And maybe the pressures of that, with four kids to clothe and feed, becomes more than one or either of them can bear. Maybe they try and try and never really get anywhere. Maybe my father goes back to drinking the way he did when he first came home from Vietnam, before he quit for good. Maybe he shows up to one too many shifts at the fire station stinking of booze, and maybe he gets shitcanned, and as a consequence he never helps deliver the 9/11 baby, never appears on the Today show.

*

While I’ve been writing this essay, another deeply sad story involving a child and overwhelmed young white-trash parents has occurred here in the Maine hinterlands. This happened in a burgh called Arundel, one of countless little Maine communities where double-wide is the preferred architectural style and yard decorations consist mainly of Bondo’d jalopies and brightly colored, broken toys. The details are horrid but clear (unlike in the Ayla Reynolds case, where the details are horrid despite their murkiness): according to a police affidavit, a young man could not bear listening to his two-month-old son cry anymore. He put one hand on either side of the baby’s head and picked him up. He pointed his elbows out to the sides and squeezed the baby’s head between his palms as hard as he could. For a full minute, he held the child this way. I can imagine the young man breathing hard, through clenched teeth, with the effort; it goes on long enough that maybe he even starts to sweat a bit. I can feel, or else hear, the soft plates of the baby’s skull beginning to slip. They are not yet made to withstand this sort of trauma; they require protection and time and they will get neither. I can imagine the pitch of the baby’s cries beginning to rise with the pressure and pain. I can imagine, all too well, that this serves only to infuriate the young man further, and that this is the moment when he decides to heave the baby across the living room. The baby hits a chair and his head snaps sharply backward on impact. I can imagine the horrible sound, and I can also imagine that this, finally, is when the baby stops crying.

Three days later, the baby, whose name was Ethan Henderson, died.

Here is what I know about Ethan’s parents: they are both twenty-three years old. They have different last names. The mother, Christina Henderson, has a three-year-old girl from another relationship: Ethan’s half sibling, in other words. The father, Gordon Collins-Faunce, was himself abused while in foster care as a child. He served in the military but was discharged for holding a knife to another soldier’s throat. He took medication for post-traumatic stress disorder. He drank too much, though of late he’d quit drinking. After all that, he decided to have a child of his own, and neither he nor, apparently, anyone else thought better of it. By his own admission, he’d broken Ethan’s arm when the baby was just a month old.

*

A vigil has been planned this coming weekend to remember Ethan Henderson, and a memorial fund has been set up, in part to raise money to pay for his funeral: the small amount of embalming fluid, the matchbox casket, the undertaker’s fee, the shiny hearse and the flowers and, of course, all those candles, which presumably cost money, too.

*

In reference to the Ethan Henderson case, Amy Wicks of the National Center on Shaken Baby Syndrome says, “You see it across all socioeconomic levels. You see it across all education levels.”

She may. I don’t. I see it right here, stubbornly entrenched in this particular socioeconomic level, the one where we scrape by selling pizzas to one another, and where a GED is pretty much the pinnacle of academic achievement. I see it pushing dirty strollers with bum wheels all over town. I see it buying potato chips and Slim Jims at the convenience store, see it smoking in Bondo’d jalopies with the windows rolled up and car seats in the back. I see it trying to hide behind TV-studio makeup jobs, smiling uncomfortably for the cameras, heaving studious sighs. I see it ignored by conservatives and excused by liberals, and then I see people from both groups arguing in the abstract about abortion and entitlement programs and the proper function and place of government in our lives, and then I see them getting together after the fact and lighting candles and posting flyers and asking how, oh how, could this have happened.

When I look at pictures of Justin DiPietro and Gordon Collins-Faunce, I think, Of course. The scraggly facial hair, the sunken eyes, the bad skin and teeth (an overall effect that one friend of mine refers to as “white-trash bone structure”) confirm my suppositions. I see exactly what I expect to see when reading about someone who threw his baby across a living room, or else reading about someone who has become both the police’s and the public’s prime suspect in the disappearance and presumed murder of a child.

I also see my cousins, and my uncles, and friends old and new. I see a picture of my father from the time he spent in Vietnam, shirtless and smiling on a pier somewhere in the South Pacific, and I see an older picture, of my grandfather, shortly before his death, bloated and beaten and bald in a powder blue tuxedo at someone’s wedding. I see myself, my own bad skin and bad teeth. I see all that I love and loathe. I see the past and the future.

Despite all the things I see, though, I still have not seen Ayla Reynolds, and do not expect that I ever will.