Come Meet Babysim!

Goethe, in his novel Wilhelm Meister’s Journeyman Years, depicts Wilhelm’s encounter with a cadaver readied for dissection—a scene likely imbued with details from Goethe’s own experience as a gentleman-student of the time. Wilhelm discovers the specimen before him is the body of a young woman who has drowned herself in despair over an unhappy love affair. Lifting the sheet that covers the body, the student spies “the loveliest female arm that had ever been wound around the neck of a young man,” and, as the vision overwhelms him, “his reluctance to mutilate this magnificent product of nature any further struggled with the demands which any man striving for knowledge must place on himself, and which everyone else in the room was busy satisfying.”

The narrator’s (and, one surmises, Goethe’s) qualms about using human bodies for medical education, as well as the often unsavory methods of the time for acquiring those bodies, are addressed by a visitor who suggests an alternative to anatomical destruction: the use of fabricated models. The visitor takes Wilhelm to a studio lined wall-to-wall with wax figures that have “the fresh, colorful appearance of newly prepared specimens.” Wilhelm is enthusiastic about the sculptor’s vision of a sanitized future for medical training, where models will replace the practice of carving up dead bodies for medical study, a practice he labels “a repugnant handicraft” that “especially among naturally moral, high-minded people… always has something cannibalistic about it.”

Perhaps it was a deep-seated fear of cannibalism driving the sixth annual International Meeting on Medical Simulation, held at the Sheraton San Diego Hotel & Marina in January of 2006. With its isolated torsos and heads, bodiless appendages, simulated arms and legs hanging in booths with entreating banners like Come Meet Babysim!, the exhibition hall I walked into felt like a triumphant pageant or a Barbie butcher shop.

“How exciting is it to be at the dawning of an emerging field?” Dr. Daniel Raemer, president of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare, asked the attendees. “So many new colleagues,” he continued with enthusiasm, “nascent ideas, groundbreaking technologies appear before us at a rate that exceeds our ability to fully embrace them.” This mood of excitement, of pioneers assembled at the edge of uncharted territory, was reflected plainly in the faces of the hundreds of eager medical professionals as they milled jovially about the chandeliered exhibition hall.

I stood surrounded by the cutting edge in fabricated human bodies, surveying a range of goods that seemed both ahead of its time and quaintly, earnestly representational—the expressions of both discomfort and entreaty on the mannequins’ faces, the personality alluded to in a blond pediatric model, “Dylan,” by his low-rise basketball shorts and endearing cowlick. The busily curious doctors and nurses exhibited no trace of hesitation and squeamishness, instead using these lifelike models for what they were—tools for learning. At booths for companies with names like Limbs & Things, they eagerly practiced intubation (the difficult task of putting a breathing tube down a patient’s throat) or slid needles into mannequins that dripped fake blood onto the floor below. Ultrasound machine probes sought out fabricated tumors and cysts coyly suspended in “phantoms,” yielding gelatinous shapes made to conduct sound waves exactly like human tissue.

“Noelle,” described as a Maternal and Neonatal Birthing Simulator, prepares students for the myriad complications of childbirth and arrives complete with a “removable stomach cover” as well as “one articulated birthing baby with placenta, four dilating cervices, three vulva for postpartum suturing, talcum powder and lubricant, instruction manual, and carrying case.” Nearby, two Italian medical students engaged in a trauma scenario with a Human Patient Simulator (HPS) named “Stan,” his vital signs veering to worrisome levels as the students endeavored to revive him, the seriousness of his condition and the failings of their treatment choices indicated by increasingly shrill alarms. Promotional material from this vendor claims that its mannequins exhibit “clinical signals so lifelike that students have been known to cry when it ‘dies.’” The company’s representative, an attractive blond woman in a pale blue suit, tilted her head at the students. “Now what did you do?” she said, her hands held on her hips in mock concern. “I’m afraid we killed him,” one of them said with a lovely accent.

As medical schools across the country contemplate replacing cadavers with virtual and synthetic bodies as teaching tools, and hospitals spend millions of dollars to offer their physicians such “high-fidelity” training mechanisms, this extraordinary collection of products seemed to herald a possible sea change for medicine itself. Perhaps this was Goethe’s dream of a clinical future populated by synthetic bodies realized, a permanent transformation of the methods of medical education—a practical end to the use of the dead. But what of the path that led the discipline here: from the vacillating proscriptions throughout history against using human bodies, to later exclusive use of cadavers to teach and practice, to now encouraging doctors to learn with high-priced, high-tech simulation devices instead? Have we at last arrived in a paradoxical age where technology has equipped us with mechanisms better suited than the human body to investigate the human body?

History of a Repugnant Handicraft

While the study of human anatomy has inarguably come a long way since its earliest days, the exuberant proclamations made by today’s simulation experts—that recent advancements in anatomical and procedural training stand as a defining moment in medicine—are not without precedent. In 1826, John Godman, renowned American anatomist of the time, declared, “the triumph of modern medicine begins, the voiceless dead are interrogated.” Despite Godman’s claim, the initial steps toward this self-designated victory had been embarked upon much earlier by a procession of inquisitive and determined speculators. Herophilus of Chalcedon is regarded by many as the “father of anatomy,” the first recorded person to have based his conclusions on actual dissections of the human body. In the third century BCE, Herophilus had free rein to pursue his investigative techniques in Alexandria, the academic hotbed of the Greek empire, during the city’s scientific and intellectual heyday, and the sole, brief era in Western medical history (until relatively recently) when human dissections were permitted and encouraged—even performing some of them in public to large crowds.

Once the succeeding Roman Empire officially forbade dissection, due to a general fear of retribution by the dead, progress in the study of anatomy and medical treatment slowed to a halt. Inquiry only returned around 150 CE, with the appearance of Claudius Galen, a Greek physician who worked as resident surgeon at the coliseum of Pergamum—a venue where over twenty thousand spectators paid admission every week to watch slaves in pairs try to kill each other. The steady supply of disemboweled and otherwise mangled patients gave Galen a limited form of access to anatomical study. Something of a gaudy showman, he then moved on to Rome and cultivated his celebrity by giving dramatic public performances with live animals, such as slicing along the spinal cord of a pig and gradually paralyzing the animal to illustrate the different parts of the nervous system. Still, most medical practitioners of the time clung to a host of inaccurate beliefs about human anatomy—for example, the “wandering womb,” a popular notion that the uterus was not a stationary organ but one that traveled impulsively throughout the female body.

Galen published On the Usefulness of the Parts of the Body, a work on human anatomy that he delivered in 17 books, composed of a staggering 434 volumes. However, Galen’s lack of access to cadavers (which he lamented in his personal writings, pining for the freewheeling days of Alexandria) meant that the bulk of his knowledge came from animal rather than human dissection, primarily that of the Barbary ape. This understandably lent Galen’s work its fair share of flaws, including the claim that humans have a five-lobed liver (as do dogs) and that the heart has only two chambers.

It wasn’t until about a thousand years after Galen’s death, as the Middle Ages were winding down and rational inquiry enthusiastically reemerged as the mode of the day, that anatomical research resumed in earnest. The curiosity of the age, applied by astronomers to the habits of planets and stars, extended easily to the unexplored universe of the human body itself, with medical and creative thinkers alike again considering its design.

But the true investigative advancements were made not by anatomists but by visual artists of the time, most notably Leonardo da Vinci. Captivated by the mysterious workings of the human body, what he called the “measure of all things,” Leonardo embraced an analogy of the larger world mirrored in the microcosm of the body. He examined cadavers privately to acquire details, and it is alleged that he kept body parts lying around his own home for close study and bargained with executioners for leftover corpses. His anatomical studies are beautifully rendered and far ahead of their time in terms of accuracy and fine detail. They reveal that he discovered how the vocal chords make sound and how the heart’s valves direct the flow of blood; he made a glass model of the heart through which he pumped seeds in water to illustrate the pathways of circulation. Da Vinci was endlessly fascinated by the act of investigation, even though he was more interested in observation than experimentation, and he never claimed allegiance to science for the sake of science, once concluding, “From science is born creative action, which is of much more value.”

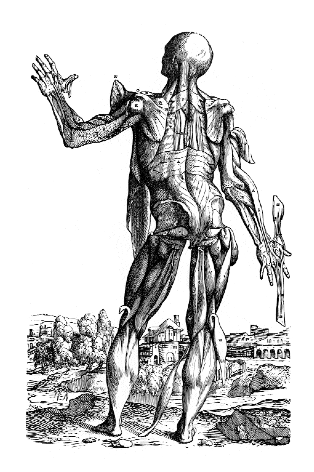

But it was physician Andreas Vesalius who changed the discipline forever. Born in 1514, in Brussels, to a family of physicians whose coat of arms contained three weasels (Wesalius), he was by all accounts a man of exceptional intellect and unlimited energy, and garnered a reputation as an enfant terrible in the scientific community of the time. Although raised on Galen’s faulty premises, Vesalius emerged from medical school to publicly and passionately argue against Galen’s views, much to the disappointment (and fury) of his formerly adoring mentors. To further his arguments, he published his own treatise, De Humani Corporis Fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body), considered by many to be the first true “modern” anatomical text. Striking for its accuracy as well as its exquisite woodcut illustrations (possibly the work of Titian or his followers), the book was published in 1543, the year that Vesalius turned twenty-nine and the same year that Copernicus published his Revolutions of the Heavenly Bodies. In the same way that Copernicus revolutionized man’s concept of his own position in the universe, Vesalius transformed the ideology and methods of medical education by positing that the body itself should serve as the primer from which an understanding of its behavior originates.

The Fabrica is a beautiful text and offers meticulous portrayals of isolated parts and illustrations of the entire body—including skeletons in various postures, situated imaginatively in bucolic landscapes. One section, titled “The head was formed for the sake of the eyes,” explains:

That eyes require a high location is attested to by lookouts for attacks of enemies and bandits, who climb walls, mountains, and high towers for the same purpose as sailors climb the masts

of ships.…

Vesalius’s promotion of a dissection-based, get-your-hands-dirty approach sparked an explosion in anatomical research, with a succession of professional anatomists in almost every country following suit, each making significant and specialized contributions to the canon. Noteworthy is the English physician William Harvey, who was so devoted to the discipline that he personally used his deceased father and sister as dissection specimens.

This upsurge in anatomical study and its growing reputation as the vanguard of medical education extended into the early 1800s in both Europe and the United States, and medical students adamantly insisted on classes devoted exclusively to individualized dissection. This insistence fueled, in turn, the dramatic acceleration of an already present problem: procuring enough fresh bodies. In the early days, anatomical models were made primarily of wax, a practice called ceroplasty, with the finest examples from Italy. One of the most famous collections is housed at La Specola Museum, made possible by the Medicis and still open in Florence today. In America, anatomy museums were all the rage in the mid- to late 1800s—ostensibly to educate the urban working classes on the dangers of wanton sexual appetites by means of graphic clinical discouragement.

The Specola collection offers its fair share of provocative viewing, although its creators aimed for and attracted a more reputable audience. The workmanship is exceptional, and the highlights of the collection include a half dozen full-size female figures, their insides laid bare as they recline on dainty satin pillows. They loll in glass cases while their torsos lie split open from their necks to their private parts, their internal organs spilling artfully over their sides. The faces are painstakingly fashioned and lifelike, conveying a moment just happened upon, as if the women are caught in daydream, their lips partially open, their eyelids heavy, fingers holding the end of a braid, or hands lying invitingly palms-up next to their eviscerated bodies.

While wax models offered a level of verisimilitude that rivaled that of actual cadavers—not to mention their expressive appeal—they were, unfortunately, not exceptionally suited to the tasks of the medical professional. They did not easily withstand excessive handling, and they were expensive and difficult to create. Goethe does not touch upon these drawbacks in his literary imaginings of a future improved by such creations, nor the frank and immutable reality that it often took up to two hundred cadavers (due to their tendency to spoil quickly) to produce a single wax model.

Several physicians and anatomists championed the so-called natural anatomy method: preservation of real bodies either in alcohol or by desiccation (corpse jerky, of a sort). One of the masters of this technique was Jean-Honoré Fragonard. His écorchés were skinned bodies elaborately posed, such as the “Horseman of the Apocalypse,” a triumphant male figure astride a similarly skinned horse. These pieces call to mind the recent “plastination” techniques and visceral nature of Gunther von Hagens’s controversial Body Worlds exhibition and provoke similar sensations of fascination and unease. Curiously, Fragonard also prepared many displays of stillborn children, fashioning them into a macabre combination of instruction and creative expression. The arteries of the fetuses were injected with wax, the muscles and nerves separated and dried into postures suggesting high-spirited movement—the figures are often identified as “Human Fetuses Dancing a Jig.”

Despite technical advances in wax modeling and other methods, the limitations of the available media at the time were unavoidable, and models were deemed ultimately insufficient to replace dissection. The demand for corpses intensified as the craze for anatomical study reached unprecedented heights. Michael Sappol points out in his book A Traffic of Dead Bodies that American medical schools hurried to keep pace, leading to a mad scramble for bodies. In 1810, Harvard Medical School felt compelled to relocate the institution to Boston proper, citing a lack of available corpses in more sedate Cambridge. Bodies were essentially pickled and packed in barrels for clandestine shipment from all over the world—smuggled across the ice from Canada and, as disease and exhaustion claimed the lives of workers during the building of the Panama Canal, stuffed in crates and brought by boat up to the East Coast.

The lack of bodies also instigated the famously distasteful methods taken up by medical students and hired “resurrection men” for procuring specimens. Sappol writes that body snatching turned into “as much a medical rite of passage as dissection itself,” and it was these habits, in addition to the seemingly cavalier attitude of students toward the bodies they obtained (in fact often brazenly disrespectful, propping sagging corpses at poker tables to pose for photographs, lit cigarettes stuffed into rotting mouths, playing cards slipped between the emerging bones of decomposing fingers), that incited a series of outraged reactions from the public. Most infamous were the so-called “Doctors’ Mobs”—incensed and violent crowds that attacked medical students and professors upon discovering fresh, allegedly stolen corpses in academic laboratories. Riots took place from about 1765 to 1884 in almost every American city with a major medical school. The notorious Cleveland riot was led by a father convinced that his sixteen-year-old daughter’s body had been purloined for dissection by a nearby medical school. After reportedly holding aloft for the rowdy crowd a hand he claimed to be hers, he and the rioters proceeded to destroy everything in the medical school’s laboratories, setting fire to the building as they left—even as a terrified doctor protested that the extremity the father brandished was the ungainly hand of a male pauper.

At medical schools today, students and physicians afford cadavers more respect than their predecessors did—with many institutions holding earnest memorials for the anonymous bodies after their use, complete with words of gratitude delivered by the students themselves. Despite progress, however, seamy aspects of the body trade persist. And a lingering association between the procurement of dead bodies and an element of criminal or depraved behavior seems to survive in the modern consciousness. Current scandals don’t help allay this impression: most notably, recent revelations that collected parts are frequently and illegally sold without donor permission. Some of these ill-gotten gains turn up as limbs, heads, or torsos in fancy hotel ballrooms for paying doctors at private conferences to practice new surgical techniques; others are sent to hospitals as inadequately vetted donors for transplants. The daughter of Masterpiece Theatre host Alistair Cooke learned not long ago that what she had buried of her ninety-five-year-old father was actually only what remained after his cancer-ridden bones had been carved out by modern-day body snatchers and shipped under a pseudonym as a “healthy specimen” to tissue processors.

Another prevalent but little-discussed ethical predicament exists in a large number of teaching hospitals. In the course of resuscitation attempts—or more accurately, as these attempts prove unsuccessful—residents are allowed to perform infrequently encountered but indispensable procedures on the failing body without obtaining permission from the family. These invasive techniques include putting in a central line, which is a catheterization of a large vein that leads directly to the heart, and insertion of a chest tube, used to drain hazardous blood, fluid, or air from around the lungs. As one instructor put it, “Are these procedures absolutely necessary to try to resuscitate the patient? No. Does the patient feel it? No.”

It’s true that without these grab-as-you-can opportunities, residents may never have the chance to practice a few difficult procedures “in the field” before having to apply them to a real patient. But in 2001, the Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs (CEJA) addressed the issue amid concerns and drafted an official policy, declaring that if “reasonable efforts” to determine what the preferences of the deceased might have been or to find someone to give permission have been exhausted, physicians “must not perform procedures for training purposes on the newly deceased patient.” Nonetheless, according to attending physicians and residents I spoke to, the practice continues unofficially and often, despite the discomfort of some involved. “It’s our medical education failing us if we can’t come up with an alternative,” one emergency medicine resident attending told me. “We don’t rob graves either, even if it might allow us more practice. Personally, I tell my residents, if you want to do it, ask the family. See if that feels appropriate to you.”

The Old Eyeball-in-the-Anus Prank

At the moment, almost all medical students in the U.S. are still required to take a full-length anatomy lab, likely their earliest and most prolonged proximity to dead bodies. The rooms are sterile and cavernous, offering rows of tanks that hold the bodies and the smell of formaldehyde, despite expensive filtration devices in place that protect the students from the chemicals. Schools usually provide one cadaver for about three or four students, and over many months they exhaustively explore the organizing architecture of the human body. Some students view the endeavor as purely tedious, and some continue the time-honored tradition of pranks—one sheepishly smiling anatomy instructor recalled a glass eyeball relocated to the anus of a corpse to peer out at a fellow dissector. Several of the medical professionals I spoke to admitted that the urge to resort to gallows humor in the face of dissecting another human can be irresistible. But an abundance of students also get out of this focused attention not only an understanding of how the body works as a whole but a sense of the human in their endeavors, a reminder that the patients they will be addressing have lived full and individual lives. Mary Jane C. Edwards, in reviewing a book on the future of anatomical study, describes her own experience as a newbie medical student facing anatomy lab: “The specimen’s left ring finger was deeply indented, and the pale circle contrasted against his tanned hand. The recognition that this cadaver was first a man—a son, a husband, perhaps a father—somehow diffused my sophomoric anxiety. Although there is a place for clinical detachment, the study of human anatomy commands a sense of reverence for the structure that holds the human soul.”

None of this increased sensitivity may matter as medical schools, spurred by rising costs and a lack of desire to dedicate time in already packed syllabi, make their move toward eventually phasing out dissection altogether. Computer databases and virtual labs are ostensibly more cost-effective and less contentious alternatives, and many institutions extol the benefits of the exclusive use of simulation technology for teaching anatomy. One such option is the National Library of Medicine’s mammoth Visible Human Project—three-dimensional male and female representations of the normal human body or “computerized cadavers”—an impressive undertaking, easily accessible to teaching institutions. The NLM’s search for candidate specimens was exhaustive, due to the strict requirements of the equipment used to position and meticulously slice the bodies. Finally, in 1993, a thirty-nine-year-old murderer who had willed his body to science, recently executed convict Joseph Paul Jernigan, was selected. Reportedly, Jernigan met the criteria, yet possessed a few curious imperfections: his appendix, tooth number 14, and left testicle were missing. A fifty-nine-year-old Maryland woman, whose provenance is more closely guarded (but rumored to be a housewife felled by an unexpected heart attack), became the first “Visible Human Female.” The internal cavities of both of their bodies were filled with latex, fixed in a waxlike gelatin, then frozen to minus 160 degrees Fahrenheit and sliced into approximately two thousand microthin slivers. Each sliver was photographed and digitized, offering unparalleled views into the microcosm of the human body. There are benefits to such a comprehensive and manageable database, especially its capacity for repeated “dissection”; while true anatomical dissection destroys the specimen, the Visible Human allows for infinite dismantling and analysis. Students can also turn to computer programs such as the Virtual Anatomy Lab, an interactive interface that lets them build their own multidimensional anatomy space, even though, as the creators concede, “realism lacks currently in both the fidelity of model appearance and the methods for dissection.”

Dr. Eric Reichman is director of the Surgical and Clinical Skills Lab at the University of Texas, Houston, and is currently in charge of creating a multimillion-dollar simulation teaching center for the medical school. He received a PhD in Anatomy prior to obtaining his MD and is considered an expert in both the virtual and the actual in teaching medicine. I asked him about virtual alternatives and the creeping elimination of anatomy labs. “It’s a loss,” he told me unequivocally. “People like me aren’t real thrilled about the students getting away from the actual body for this,” he continued, “despite administrative concerns about storage and cost. Because once you feel it, once you dissect it, once you do it, you have such a better understanding for it. That ‘aha’ moment—‘this goes here, this connects to this.’ Playing with the computer, it’s not the same.”

On a recent spring day, ten emergency medicine residents gathered in the windowless basement of a medical school for a “procedure lab,” a course that affords residents in procedure-based disciplines the opportunity to practice techniques on cadavers in an intensive one-day session. The corpses for this purpose are often preserved only by refrigeration to keep the tissue response similar to that of a living body. One instructor told me he makes runs to a slaughterhouse to procure vats of cows’ blood (signing a release promising he won’t use it for foodstuff preparation), which he then injects into the bodies to simulate actual bleeding when they are cut into. “It’s one of the limitations of the cadavers that I try to compensate for,” he explained. “Probably a little above and beyond the call of duty, but it makes a difference.”

The lab took place in the room used to store the medical school’s entire supply of cadavers, and each corpse lay face up on a narrow shelf, its head wrapped with a blue absorbent cloth. The students succumbed to a brief period of nervous joking and fidgeting before getting down to the serious business—two cadavers, each shared among five residents. They began with arthrocenteses, sticking needles into all of the skeletal joints of the body for aspiration, from the shoulders down to the toes. Next they worked on inserting central venous lines: large IVs pierced into the neck, chest, and groin for fast access. They moved on to chest tubes, threading large plastic hoses between the ribs into the chest cavity to drain blood or air. The room was quiet except for the voice of the instructor and the sounds of bodily industry; one student mistakenly hit the spleen, and everyone, including the embarrassed perpetrator, laughed out loud in the echoing, tiled space. After working on the airway, the students reached the denouement: thoracotomies. They sliced from sternum to armpit and then cracked open the chest with rib spreaders (a contraption that looks straight from the plumbing department of Home Depot) for fast, disturbingly noisy access to the heart. Each resident got to practice each procedure once on the cadaver, so by the time they were finished, every nook and cranny had been used. The instructor had warned me beforehand that the corpses would be “shredded up for the most part.” After the session was over, the bodies of the two elderly men on the tables had given all they had, looking like defeated accordions, their sides filleted dramatically, their chest cavities gutted open.

Afterward, in a bar near the hospital, I asked the residents what they thought of the experience. Charles1 told me that it was “possibly the most effective five hours of my residency.” They said they never or rarely got to hone these skills on living patients, maybe once if they were lucky before heading to their first jobs as attending emergency physicians. Another resident, Pete, informed me that at his medical school they had been given only giant slabs of beef ribs on which to practice putting in chest tubes. “Then we could take them home and cook them up if we wanted to,” he said, adding, “I went to med school in Louisiana.” I asked them about simulation, what their experience had been with models. “They’re good for certain things, practicing how to hold the tools, how to approach,” Charles allowed, “but, like, say for airways, the tongue never feels like a real tongue, it’s never floppy enough.” He laughed. “And you never suction a mannequin, there’s never any vomit or blood coming up out of the throat. There’s never an attending behind you screaming ‘You’re losing him, you’re losing him!’ ” Not yet, anyway.

I asked the residents what they thought about future medical students not having to dissect in an anatomy lab as they themselves had been required to. “That’s crazy,” Clare responded. “Yes, some people cried, some people passed out, some people threw up. But they got over it, they learned something really important.” Charles was equally passionate. “It’s a crucial part of medicine, part of learning. You have to do it. Just as much as you get out of it on a technical level, there’s an emotional component to it too.” He paused. “It’s weird. It teaches you to be desensitized in some ways, but it oversensitizes you at the same time.” Would they donate their own bodies to such an endeavor? I asked. They thought seriously about it. Yes, they all agreed, finally. It was essential. “But they better treat me right,” Pete added, lifting his glass.

In all likelihood, we as patients benefit from specialized use of the artificial to prepare physicians for situations with the real. Dr. Reichman insists that, despite the limitations—“yes, the rubber does stick, it’s harder to get through”—models are undeniably helpful because they can be repeated on again and again. Surgeons will refine new procedures on virtual patients—confronting countless permutations, learning guiltlessly from any mistakes—instead of only trying once on a cadaver pumped full of animal blood, or worse, on a potentially suspect corpse at a weekend seminar. There will be fewer surreptitious rehearsals of tricky feats by residents on a recently deceased patient. There will be more time allotted to hone these skills than one-day sessions in a lab, particularly as mannequins become less expensive and more lifelike in their responses.

The medical simulation industry understands this, and is working hard to replicate human distress and malady, bodily response and behavior, and getting better at it all the time. While at the International Meeting on Medical Simulation, I practiced virtually operating on a brain aneurysm with slender robotic instruments and a lifelike display to guide me, as if playing the world’s highest-stakes video game. I tried to put central lines and breathing tubes into “patients” who communicated their distress until I felt ridiculously responsible for their survival. I took part in a bizarre but educational demonstration, “Delivery of Infants with Shoulder Dystocia,” which used “pregnant” mannequins to practice managing difficult births, over and over, in hopes of avoiding a serious condition that tears the nerves along an emerging baby’s neck. And I sat in a workshop, “Saving BabySIM at 6 Months!,” where medical professionals gravely rehearsed lifesaving techniques on high-fidelity infant models who cooed and cried (and died) convincingly. Encountering the impressive range of applications, I find the benefits of simulation in preparing for challenging scenarios almost impossible to argue with.

It is possible that, as a society, we have come to prefer for most tasks the clean and modern, the culturally unmessy, favoring, like Goethe, something that won’t make us squeamish or pensive the way a corpse might, that doesn’t seem so archaic and gruesome, in a time in the Western world when the visceral experience of death is far removed for all but a few. Still, there’s no denying that the medical simulation industry goes out of its way to conjure a faithful human aspect in its products: The faces are not left blank, the models are given names and sometimes voices. Even the term phantom, applied to those compartmentalized sections of the human body used for ultrasound training, seems deliberately chosen to evoke a sense that these pieces are more than clinical tools, are so lifelike that they are practically haunted by a human energy, a fidelity to true organic human response. The industry appears to be responding not just to a need to replace the technical aspects of the body but to some deeper emotional aspects of working on them as well. And perhaps simulated bodies can provide, beyond specific technical training and repeatability, the particular sensation of something “living” passing away on one’s watch as the result of one’s decisions. These surrogate patients offer a version of the immediate experience of the moment of dying, as distinguished from interaction with a body that is already dead.

But in replacing in-depth dissection with facsimile—images of microthin slices of the human body, computer programs with video gaming technology—might something irreplaceable be sacrificed? Could cadavers absent from anatomy classes take with them a crucial and foundational confrontation with death, of the incontrovertible and candid meatiness of the human body, which cannot be conveyed with the perfect resilience of plastic and wire, or the efficient entertainment of a virtual odyssey? Might something of the awareness that has been so resolutely pursued by anatomists throughout history vanish as well—an understanding that the human body is an intricate system more than the sum of its parts, the starting point, as Vesalius posited, from which all medical knowledge is derived, deserving of careful exploration? That it is a complex mechanism, but not a machine—that the life’s work students will be pursuing as physicians concerns human bodies after all? In the eighteenth century, a visitor observing the anatomical wax modeling skills of Mlle Biheron—one of the few female model-makers of the time and considered one of the finest of either sex—is reported to have commented upon seeing her handiwork: “Mademoiselle, there is nothing lacking but the stench.” We can speculate, in this blossoming age of medical technology and its bounty of virtual patients and spaces, as dead bodies gradually disappear from early medical training—no longer serving as strangely intimate workmates or as prompts of a sort to limn exactly what is involved in such a calling, a lifetime of addressing the human body—that there may be something future physicians will miss, beyond the smell.