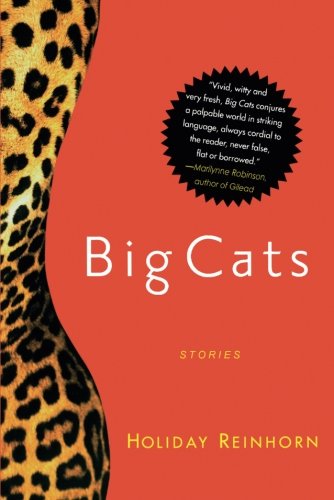

I liked Holiday Reinhorn’s debut short story collection, Big Cats, so much that for three weeks after I finished reading it, I drove aimlessly through the desert outside of Las Vegas, through Arizona and New Mexico, and across most of western Texas. I filled my trunk with copies of Big Cats. I spent my days carefully cutting Reinhorn’s stories from the books, enclosing them in Ziploc freezer bags, and burying them in shallow holes.

If short stories are seeds, Big Cats contains thirteen seeds that will sprout from the cracked earth and ripen into gorgeous Saguaro cacti. Reinhorn’s stories are spongy, prickly things that share a kinship with those planted by readers of Raymond Carver and Tobias Wolff. Like these writers, she photographically renders a bloody-hearted world full of delicate people who need to be held in the palm of your hand.

Most of the characters in Big Cats find themselves wanting to break free of the past that keeps them rooted. They push grocery carts in the mega-grocery stores, but like David in “Get Away From Me, David,” they keep DayQuil in their desk drawers at work in case remembering who they are (and not who they want to be) becomes too unbearable. In “Charlotte,” a young girl and her brother watch their neighbor and her ex-husband run through their front yard sprinkler as if “they’d never figured out how good cold water could feel in the middle of July.” Charlotte is reminded of her own mother, Bobbie, who is gallivanting around town with her threepenny boyfriend, and realizes that her mother’s life has sunk well below the point at which she once dreamed it would peak.

The passage below is from “The Heights,” a story I buried thirty-five miles due east of Tucson, Arizona. Elizabeth wants to become a doctor like her father, now confined to a wheelchair in a catatonic state. In her family’s parlor one afternoon, Elizabeth watches her mother, post-golf, flirting with her husband’s old doctor friends as her father vacantly observes.

Maybe, like me, they have never seen a man cry. Although Daddy’s nurse says he does that sometimes. Sometimes water will squeeze out the sides of his eyes when he’s lying on his back. She calls it crying, and even though I read in my survey on neurological dysfunction that this can just be from pressure, they are not actual tears, I don’t correct Daddy’s nurse when she treats them as if they’re real. I think the tears Dr. Al is shedding now must be pressure of a similar kind. So I leave Daddy by himself, and I go to Dr. Al. I step around my mother and place my hand over both the hands he operates with. I hold them there. The skin under my palm is hot and dry and chapped-feeling, and as soon as I touch him, he closes his eyes.

There is a deep, earned melancholy in these stories, in which the characters are repeatedly thumped with the realization that life slips gradually from the grasp of those who are living it. On my way back to New York, somewhere in the middle of Illinois, on a two-lane highway surrounded entirely by corn, I stopped my car, leaned across the front seat, and fished a Ziploc bag from the glove compartment. I had one story left, folded up in the back pocket of my jeans. I put the story in the Ziploc bag and sealed the top. The hole I dug was shallow. On my knees, I patted down the newly upturned earth.

—Theo Schell-Lambert