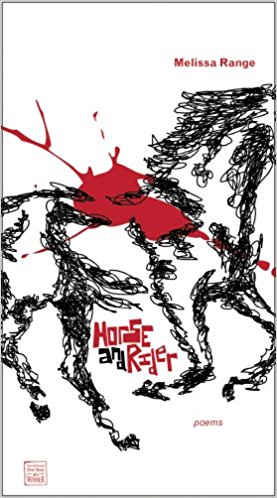

“There is no progress in the arts,” said the radical William Hazlitt, and he was right: the problem with most so-called new formalist poetry is not that the poets write as if it were 1953, but that their poems would not have attracted interest—might not have seemed skillful, or even competent—by the standards of 1953. It’s distressingly hard to find new American poets best served by traditional prosody, by terza rima or by couplet rhyme. Hard, but hardly impossible. Melissa Range is one such poet, and her immersion in traditions—religious and regional, as well as metrical—has led to an exciting, disturbing, promising, if also brief, first book.

It is a book of the American inland South, of Range’s natal east Tennessee, the “dark and bloody ground” from which white men expelled the Cherokee. The plant called bloodroot represents “blood shed / beneath the surface of the world,” blood shed by Range’s forebears, on her behalf: “stain me red,” she asks, “and bury me with my people.” At her best—perhaps half the time, here—she can master a cascade of rhymes without abusing the shapes of American speech. She says of a worn-out workhorse, for example, “Too much sweetgrass made him lame, / or we did; too much bridle made him tame, // which we did. Nails in his foot / mean he’s not good-for-naught,” and the rhymes canter on till the poem, and the horse, meet their ends.

Even more than it is a Southern book, Horse and Rider is a war book, attentive not just to the Indian Wars but to Iraq and Afghanistan obliquely, to Homeric Greece and to Beowulf’s England directly. The middle third of Range’s volume consists of poems spoken by implements of battle, from a wooden shield to a hand grenade. “The Battle-Axe” cuts through pretensions, the working-class rival to the aristocrats blade: “knights want to battle and die/ by a princely, pricey sword. That’s comical. / I deal death as death should be:/ commonplace, quick and economical.” Other weapons are less aggressive in their wishes, though equally fatal in their effects. A rope would rather be anything but a noose; a javelin implores, “Sight your target and fling me// goodbye. I want to be held,/ but I want more to fly.” Such poems may look like exercises, and the worst poems here do feel like assignments, but the best end up more thoughtful, and more energetic, than most poets’ most clearly personal work.

As much as it is a Southern book, a war book, and a compendium of forms, Horse and Rider is first and last a religious book: the record, apparently, of a passionate, left-wing, anti-war Christian, whose faith never gets in the way of her irony. Her final poem (drawn from a remark in Dostoyevsky) offers a supplication to the birds, saying the best that can be said for human, institutional, credal religion: she asks that the innocent avians “Forgive us as priests // in slums and picket lines forgive the church: / in vigilance, mining the breach — // that sky—for something that will not be owned.” Range is never without mixed feelings, never content just to curse, nor to praise, nor to pray. She can channel those mixed feelings into quiet understatement, but she is more often, and more effectively, forceful, as in the bitter couplets (some freely translated from the battle hymn in Exodus 15:1-19) that comprise the title poem: “Sing unto the Lord, for He has triumphed gloriously… He has shown Himself worthy of all our noise:/ He has rid the earth of a few more horses, a few more boys.”