The Notoriety Traders

In his influential 1961 book The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America, scholar Daniel J. Boorstin noted that “the successful dealer in literary, dramatic, and musical commodities is one who discovers a formula for what the public wants, and then varies the formula just enough to sell each new product, but not enough to risk loss of the market.” For the entirety of its hundred-year existence, mainstream American cinema has so faithfully operated on this formulaic-variance principle that it’s hard to watch a Hollywood action movie or romantic comedy without instinctively knowing what’s going to happen next. Even when these movies surprise, the audience knows that all surprises exist within the accepted formula of what is and is not expected.

Historically, B movies have existed as simplistic, inexpensive distillations of Hollywood’s big-budget genre fare. When a mainstream film like John Ford’s 1939 Stagecoach dazzled western fans, B westerns began to mimic its flashier elements (blazing gunfights, constant suspense, “type” characters) to attract audiences. Similarly, when Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho thrilled moviegoers in 1960, B horror films went to outrageous lengths to provide similar shocks and frights on a small budget. Since most B-movie plots derived from better-financed A-movie formulas, they were forced to set themselves apart through gimmickry: outlandish characters and settings; titillation and exploitation; silly PR stunts (such as distributing barf bags before gore-horror movies, or installing seat-buzzers to startle sci-fi fans); and titles so outrageous—think Women in Bondage, I Was a Teenage Werewolf, and Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!—that the name alone could help a movie achieve cult status.

In recent years, the most vivid legacy of this B-movie gimmickry has been the emergence of “mockbusters”—cheaply produced straight-to-DVD films with names like Transmorphers and The Da Vinci Treasure—created with the clear intention of trading in on the notoriety of theatrical films like Transformers and The Da Vinci Code. In one sense this is nothing new, since mainstream movies and B movies alike have always cannibalized successful templates. What sets mockbusters apart, however, is that these films are deliberately released on DVD just as their blockbuster namesakes hit the big screen, thus creating a niche market based on simple consumer confusion.

Track the history of mockbusters, and you’ll find that one independent production company, the Asylum, is responsible for most of the titles in this curious sub-genre. In 2005, for example, the Asylum released a DVD version of War of the Worlds to video stores one day before the Steven Spielberg movie of the same name appeared in movie theaters. American movie fans who rented this DVD were no doubt startled when the sci-fi tale opened with a T and A nude scene, and starred an emaciated C. Thomas Howell instead of a buff Tom Cruise. A few months later the Asylum beat Peter Jackson’s King Kong to the video shelves with its own giant-ape movie, King of the Lost World, featuring Babylon 5 alum Bruce Boxleitner and a certain Jeff Denton. In 2006 the Asylum’s The Exorcism (featuring Jeff Denton) found video store shelf space alongside The Exorcist around the same time its Pirates of Treasure Island (also featuring Jeff Denton) jumped the gun on the newest Pirates of the Caribbean sequel. By the end of that year, the Asylum had also produced direct-to-DVD movies titled 666: The Child and Snakes on a Train.

Of all the films in the Asylum catalog, few movies reveal the quirks and contradictions of mockbusters quite so vividly as Transmorphers (released to coincide with the Michael Bay 2007 blockbuster Transformers) which mashes elements of The Matrix, Star Wars, The Terminator, Starship Troopers, and Battlestar Galactica into a cheaply produced, virtually incomprehensible movie about evil robots controlling the earth. In addition to its borrowed plot elements, the movie’s dialogue resonates like an ongoing tribute to sixty years of action-movie clichés: The team is still inside! They’re launching a massive offensive! We’re running out of time! Everybody get back! Cover me! Watch the crossfire! They’ve breached all perimeters! Start the evacuation process! We have to wait for the others! I’m going back for her! Suit up, it’s going down! I wouldn’t miss this for the world! We got one! Follow me! I’ve always loved you! I always will!

Amid all of this, Transmorphers never once betrays a moment of self-referential humor, even as it features sexy lesbian commandos, T. S. Eliot references, and computer-animated robots that look like they were lifted from an early 1990s video game. Movies like King of the Lost World and Pirates of Treasure Island are similarly earnest—and this is perhaps the most singular quirk of mockbusters: while classic B movies made up for low budgets with campy moments of comedy, the Asylum’s films are resolutely self-serious—often far more serious than the titles they mimic (the somber, slow-paced Snakes on a Train being a prime example).

In a way, the word mockbuster (first coined in a 2006 New York Post article) is misleading, since the films in question don’t satirize their blockbuster namesakes so much as they tweak titles to market cheap, straightforward genre movies. This narrative earnestness hearkens back to the earliest, pre-camp, pre-exploitation, lower-bill-on-the-marquee B movies—though cynics could just as easily allude to the opportunistic gimmickry of porno-movie nomenclature, since The Da Vinci Treasure no more resembles The Da Vinci Code than On Golden Blonde resembled On Golden Pond.

More Blood

Late last summer at the Asylum’s West Hollywood offices, a contract director named Scott Harper gazed into a video monitor as production assistants slathered fake blood and slime onto an actor wearing an insect-like alien costume. Harper’s movie Alien vs. Hunter (rushed into production to compete with Twentieth Century-Fox’s Aliens vs. Predator: Requiem) was using recycled elements from a film shot at the offices the previous week (I Am Omega, an I Am Legend knockoff)—in this particular case, a moss-draped sewer tunnel.

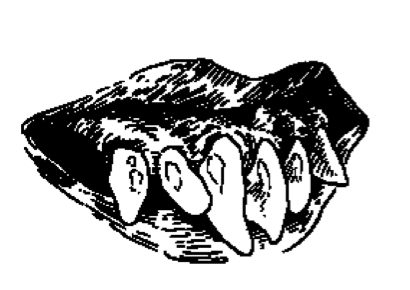

“Somebody needs to fix the intestine,” Harper said, gesturing to the blood-smeared tubes flopping out from the alien’s foam-latex teeth. “Put the big piece of intestine down the cleft of the chin. Like that. Good. So in this scene you’ll just be chewing the intestine. React to the noises, but it’s important to keep chewing the intestine. What’s that? All right, I guess Tara needs to go and make more blood, so let’s take fifteen minutes.”

In a far corner, a production assistant dumped bags of gardening soil into a wooden frame that would later serve as a crawl space for an escape scene; outside, another assistant slathered gore and grime onto an actor in a tiny costume trailer. In a makeshift greenroom not far from the office reception desk, I met the stars of Alien vs. Hunter—William Katt (best known for his lead role in The Greatest American Hero twenty-five years ago) and Dedee Pfeiffer (whose older sister Michelle was just a mile up La Brea Avenue that very afternoon, getting her star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame).

Pfeiffer, cast as a tough-girl flower-shop owner named Hillary, told me how the Asylum offered her the role one day before shooting began. “This was literally a last-minute thing,” she said. “They sent me a script and told me they wanted an answer in an hour. When I asked who else had been cast, they said ‘nobody.’ I came on set the next morning and found out I was working with Bill.”

Katt, who was playing an intrepid reporter named Lee, said he learned about the Asylum from a friend in the Screen Actors Guild. “I wouldn’t have done this if the script hadn’t been as good as it was,” he said. “These guys are fun. They’re actually making movies while everyone else is just talking about it. There are very few of these kind of companies around anymore.”

Name stars aside, Asylum movies draw on a pool of several dozen actors and crew, who sometimes refer to themselves as “Asylumites.” Check the IMDb.com credits of any Asylum production, and you’ll see actors doubling as editors, directors who worked as production assistants a few months prior. Some seem to have used the Asylum as a de facto film academy: Justin Jones, who was serving as first assistant director on the set of Alien vs. Hunter, started as an intern with the company in 2004 and has since gone on to act or crew in more than forty Asylum projects—including Invasion of the Pod People (filmed to tie in to Nicole Kidman’s ill-fated The Invasion), his 2007 directorial debut.

Though the indefatigable Jeff Denton wasn’t working on the Alien vs. Hunter set, I did meet Jason S. Gray, who’d acted in nine Asylum films since his 2006 debut in The Da Vinci Treasure. Powerfully built, with an ambiguously ethnic look (he’s played Arab, Mexican, and Serbian characters in various Asylum movies), the thirty-year-old actor told me he considered his involvement with the company his biggest break since arriving in Hollywood from Indiana in 2002.

“I feel lucky the Asylum took a chance on a guy like myself,” he told me. “The pay isn’t much by Hollywood standards, but this isn’t about the money for me: I’m getting the kind of experience I would never get at a big studio. I work here because I love making movies, and I love being on set. They let me do more than just act. It’s like a free film education. I’d rather come here and help with the lights than stay at home and wait for DreamWorks to call.”

Mockbuster v. Tie-in

Upstairs from the greenroom, in an office loft that featured prominently in Invasion of the Pod People, I found David Latt, a sardonic, boyish forty-one-year-old who founded the Asylum with partner David Rimawi in 1997. In its early years, the company focused on producing low-budget dramas and comedies by first-time directors. Though distributed by Hollywood Video under a program called “First Rites,” these art movies never managed to turn a profit. “Everyone always complains about why production companies don’t make more interesting and thought-provoking movies,” Latt told me. “The answer, as we learned, is that people don’t rent them. So we pushed in the direction of the market and started making horror movies.”

Buoyed by a burgeoning international DVD audience, these slasher films proved successful for the Asylum until 2005, when bigger, savvier companies noted trends and began to corner the market on low-budget horror. According to Latt, the Asylum accidentally discovered mockbusters that same year, when his own adaptation of H. G. Wells’s War of the Worlds hit video stores around the same time Steven Spielberg’s big-screen version hit cinemas. When Blockbuster ordered one hundred thousand copies of Latt’s War of the Worlds (seven to eight times the typical order for the Asylum’s horror movies), he and Rimawi reconsidered their business model. By 2007 the Asylum was producing a movie a month, and half its slate consisted of “tie-ins”—Latt’s euphemism for mockbuster movies. “We’ve gotten to where we can preproduce tie-in films in one to three weeks,” he told me. “Everything is already in place: We already have the vendors in place, and we write the script around the locations we have. We’re fully self-financed, but our margins are tight. The money we make goes into new productions. We’d love to be making theatrical movies, but we’ve gotten too good at the low-budget process: give us a million dollars and we’ll make you ten movies.”

Since campy, self-referential comedy has been a mainstay of B movies since the 1960s, I asked Latt why movies like Transmorphers or Snakes on a Train were so devoid of humor. “Creatively, we’d love to veer into camp,” he told me. “The problem is that humor does not translate internationally. Over 40 percent of our profits come from overseas sales, so we can’t get satirical if we want to keep our doors open. I know it may sound cheesy, but we look at this as a challenge, and an opportunity to keep making new films. So if a Japanese buyer wants a serious movie about giant robots, we’re going to try and make the best giant-robot movie we can, given our resources.”

At times, skewing toward niches in the direct-to-DVD market can yield curious results, such as the time in early 2007 when the Asylum’s Japanese clients requested a submarine movie. U.S. buyers weren’t all that interested in submarines, but they did see a market for giant-creature movies—so the Asylum ransacked the old Jules Verne tale 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and made 30,000 Leagues Under the Sea, starring Lorenzo Lamas. “It was the perfect compromise,” Latt told me. “The big submarine battles made the Japanese happy, the giant squid satisfied our domestic buyers, and we got to make a really fun movie.”

Since 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea is in the public domain, rights issues weren’t a problem—and thus far the Asylum has managed to avoid legal tussles with its mockbuster titles (though Universal did threaten a cease-and-desist order when the initial King of the Lost World promotional art was too close to that of King Kong). Still, the inherent opportunism in releasing mockbuster titles has attracted a lot of scorn and ridicule from online movie buffs.

“We get a fair amount of criticism about tie-ins,” Latt noted, “but we’re just doing the same thing as publishers and news outlets who follow a trend when a big movie comes out. Once a topic is discovered, all kinds of tie-ins occur. For example, when The Da Vinci Code was made into a movie, you saw all kinds of news features and History Channel specials and tie-in travel guidebooks. In making The Da Vinci Treasure, we were just taking a topic the world was already interested in and giving viewers a new product. The titles might be similar, but our stories are original.”

Nonetheless, confusion at the video store can occur—as evidenced by the father of an Asylum employee who once rented Latt’s War of the Worlds on DVD, thinking it was the Spielberg version. Moreover, in the summer of 2007, so many Transformers fans accidentally downloaded a pirated online version of Transmorphers that it achieved a rare honor in an age when most B movies are ignored entirely: it was voted onto a list of the top-hundred all-time worst movies at IMDb.com, briefly holding the number-eight slot at the end of the summer.

Though tie-in movies like Transmorphers have proven to be modestly profitable for the Asylum, Latt acknowledges that the mockbuster approach might not work forever. “Tie-ins have been key to our success in recent years,” Latt said, “but our marketing strategy is always changing. It’s not really a conscious thing. We move into new directions because we love making movies, and that means we change with the market.”

Thanks to these market trends, one of the most successful Asylum movies of 2007 was The Apocalypse—a Deep Impact–meets–Left Behind disaster thriller aimed at the Christian DVD market. “We were planning on making it as a straightforward doomsday movie,” Latt said, “but certain buyers told us they wanted a religious film. So we took the script to priests and rabbis and made it into a faith-based film about the end of the world. The Asylum had a reputation for horror, so we created a new distribution label, Faith Films. We’re looking forward to making more films that incorporate theology. The Book of Revelation is so meaty for a filmmaker—there’s just so much drama and excitement going on there.”

By the very nature of the Asylum’s international distribution system, these “Christian thrillers” will have to incorporate enough action and gore to play for non-Christian audiences overseas, but Latt didn’t seem intimidated by the challenge. “Every studio has an auspicious start,” he added. “Columbia was doing crappy B movies when they started; Universal was making low-budget horror films. We’re not the first to climb this mountain—we’re just the most obnoxious.”

Watch The Apocalypse (which involves good-looking characters racing around California, spouting vague spiritual truisms as asteroids smash into the earth), and it’s hard to disagree with Latt’s self-deprecating observation. But opportunism is nothing new in the movie business, and even big-budget movie moguls will admit that half the definition of success in Hollywood is capturing people’s attention in the first place.