DON’T LET ME BE MISUNDERSTOOD

The door swung open and there she was: Nina Simone, alone in her dressing room, sweat cascading down her shaved head, a wig thrown to the floor and two glittering fake eyelashes mashed unceremoniously against the mirror.

It was after midnight and the compact and muscular woman radiated anger following a performance at the smoke-filled Village Gate in New York City. “She was scary, for sure,” recounts playwright Sam Shepard, who during the summer of 1964 was a twenty-one-year-old busboy tasked with delivering ice to chill Simone’s champagne.

Only moments before, her long fingers arched over a black Steinway, Simone held the audience rapt, even terrified. “Mississippi Goddam,” her first bona fide protest song, had caused ripples across the country, especially in the South, which was roiling with racial unrest. And in her version of “Pirate Jenny,” the Bertolt Brecht–Kurt Weill song about a beleaguered hotel maid who vows revenge when a pirate ship returns to liberate her, Simone added a biting pathos all her own.

And they’re chainin’ up people

And they’re bring’em to me

Askin’ me, “Kill them now, or later?”

Askin’ me!

“Kill them now, or later?”

[…]

And in that quiet of death

I’ll say, “Right now… RIGHT NOW!”

“It was absolutely devastating to watch,” says Shepard. “It was a real performance as well as just being something heard.”

During the riveting and historic concerts Shepard witnessed that summer, Simone was herself devastated, descending into a terrible darkness. “Must take sleeping pills to sleep + yellow pills to go onstage,” she wrote in July 1964, referring to Valium. “Terribly tired and realize no one can help me—I am utterly miserable, completely, miserably, frighteningly alone.”

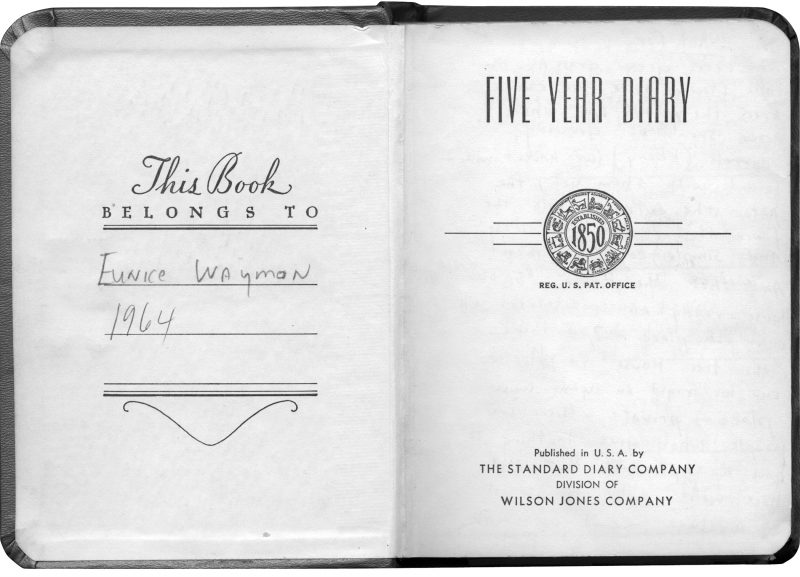

Every night after her shows that summer, Simone drove home to Mount Vernon, New York, a leafy suburb of Manhattan where prominent blacks were living at the time, including Malcolm X. There, unknown to anyone save her husband, she kept a small, leather-bound diary, inscribed, “This book belongs to Eunice Waymon,” Simone’s given name growing up in rural North Carolina. While she electrified audiences in Greenwich Village that night, a musical icon in the making, she struggled privately with mental illness, likely bipolar disorder. In the 1960s, that diagnosis didn’t exist, so Simone was left to manage her erratic moods in any way she could: psychoanalysis, hypnosis, drugs, sex, and, ultimately, writing.

“Now we have names for that shit,” says Shepard. “Back then nobody had names for it, nobody was categorizing it. It was part and parcel of what it meant to be an artist.”

By turns luridly raw and heartbreaking, Simone’s diary and letters illuminate her defining years as an artist, before she left the U.S. in 1972 for an itinerant life overseas, a single mother and divorcée, broke and wildly unstable. It’s the period when she first embraced protest music against a backdrop of crushing self-doubt and ambiguous sexual identity. For every step she took toward personal freedom, drawn to the liberation ideologies of the 1960s, her dream of wider acceptance slipped further from reach.

“I can’t be white and I’m the kind of colored girl who looks like everything white people despise or have been taught to despise,” she wrote in an undated note to herself. “If I were a boy, it wouldn’t matter so much, but I’m a girl and in front of the public all the time wide open for them to jeer and approve of or disapprove of.”

Simone’s music has survived the decades precisely because of how strange and impossible to categorize it seemed forty years ago. The oddly masculine register of her voice, its raw quaver, was and is an acquired taste. Years later, it’s more obvious how, in the absorbing melancholy and pained beauty of her early songs, she was channeling the sexual and racial searching of the era, which is why she’s since become both a gay and black icon. In 2008, Barack Obama named Simone’s “Sinnerman” among the top ten tracks on his iPod, prompting Sony to quickly release the boxed set To Be Free: The Nina Simone Story. Contemporary artists like M.I.A. and Antony Hegarty, breakers of ethnic and sexual barriers, have cited her as a crucial inspiration. The first authoritative biography of Simone, Nadine Cohodas’s Princess Noire: The Tumultuous Reign of Nina Simone, appeared this year. And this fall, production will begin on the biopic Nina, with Mary J. Blige cast in the title role.

Simone’s ex-husband Andrew Stroud, a cantankerous man of eighty-four living in the Bronx, has rarely spoken about his nine-year marriage to the famed songstress in the ’60s, and never before given access to his cache of Simone’s writings. He refused to talk to Simone’s biographer. But after a year of cajoling, Stroud agreed to open up for this story, if only to help sell a small catalog of CDs and DVDs he’s packaged from home movies and leftover recordings.*He has kept Simone’s papers in pristine condition, though loosely organized. Many notes had to be dated from the content of the material; some could be pegged only to a general period. But what is immediately striking is how lucid and candid Nina Simone could be, how easily she could tap her emotions in writing, and how, occasionally, she seemed to take great solace in getting thoughts on paper, often in her most desperate hours. Having studied at an all-girls boarding school as a teenager, her grammar and spelling are flawless. And at her most self-aware moments, her language is informed by psychiatry, a result of time spent in therapy in the late ’50s and early ’60s.

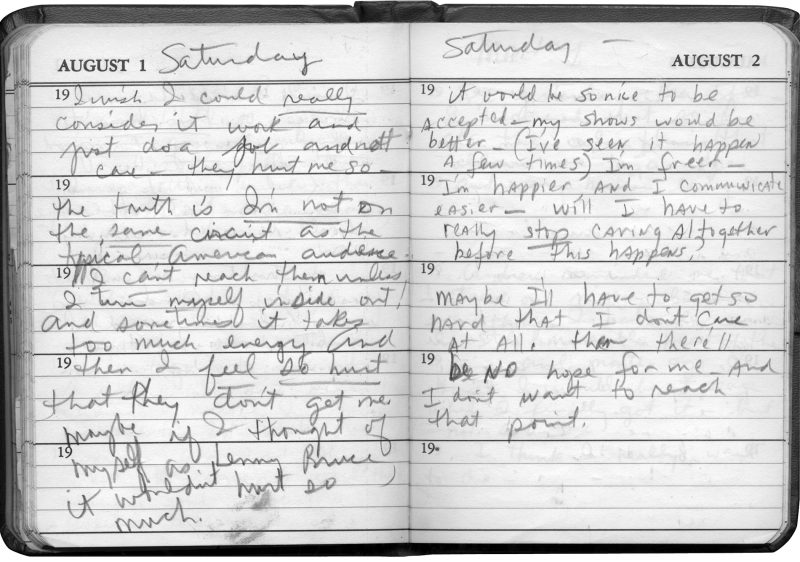

But the tumult of her life just as often leaves her scratching for the barest clarity, entering raw fragments and ideas, drugs she consumed, the sex she had the night before. When she’s happy, her writing is in a lovely, flowing cursive; when depressed, a sloppy chicken-scratch. And when her mania has reached a critical mass, she defaults to large printed letters, virtual billboards that scream from the page.

I LOVES YOU, PORGY

“Did you come in here to hear me sing or come here to talk?” seethed Nina Simone, halting midway through a song at Abart’s Lounge, a jazz club in Washington, D.C. It was the late 1950s and the mixed-race crowd watching her on a stage behind the bar went stone silent. “I want it quiet when I sing, goddammit!’”

In the crowd was a young Vernon Jordan, future head of the National Urban League and Bill Clinton’s lawyer in the 1990s. “When she was performing, it really pissed her off if somebody was having a conversation,” he recalls. “I was a great fan. I loved it when she would say, ‘Shut the fuck up!’”

It was a shocking display of impropriety from a female entertainer, especially a black woman, but this was Simone’s reputation from the start. She was considered eccentric. A 1960 profile in Rogue magazine noted that she was “painfully fragile… sliding back and forth between a sulkiness bordering on the moribund and frenetic, fleeting ecstasies of happiness.”

What inspired her outbursts was less overt racial anger than a desire for the decorum and dignity she associated with classical music. It had been her escape from poverty in Tryon, North Carolina, where she was born in 1933, her mother a stern country minister, her father a handyman who played guitar. At fourteen, Simone began piano lessons with a white British teacher in town whose neighbor had discovered her while Simone’s mother cleaned the neighbor’s house. Simone, who had played only church hymns to that point, immediately fell in love with Bach. Her white benefactors raised money to send her to the Juilliard School in New York in the summer of 1950. After one semester, however, Simone’s money ran out and she moved to Philadelphia, where her family had relocated, to try entering the prestigious Curtis Institute of Music for more piano studies.

To her dismay, she was rejected. For years, she would believe it was because of her skin color, though she later learned that other black students were accepted. But it was a fortuitous rejection: Forced to give music lessons to earn a living, she met college students who encouraged her to play pop music in nightclubs, starting with the Midtown Bar in Atlantic City. It was there she first tried interpreting jazz standards as “Nina Simone,” the made-up name she used to avoid her mother discovering her alternative life.

“All my life I’ve felt the terrible pressure of having to survive,” she told Rogue. “Now I’ve got to get rich…very, very rich so I can buy my freedom from fear and know I’ll have enough to make it.”

Typical of Simone was a 1961 show at New York’s Apollo Theater, when she refused to perform to a packed house until she was paid in cash. When told the money was in an envelope on the piano, Simone walked onstage to wild cheers, only to sit down and count the money out, bill by bill. Satisfied, she got up to take it backstage but fell backward over her piano bench, eliciting roars of laughter and applause.

“Don’t applaud! Don’t applaud!” she screamed. Al Schackman, Simone’s main guitar player for forty-four years, recounts that when some in the audience replied, “We love you, Nina!” Simone shrieked, “No, you don’t! You don’t love me!” and scrambled offstage. She returned minutes later as if nothing had happened and played a full set.

Simone first gained notoriety in 1959 with her take on George Gershwin’s “I Loves You, Porgy,” singing the song as if it were her own private confession. She told interviewers she meant it to be about the man she’d just married, a white beatnik named Don Ross whom she met in New York but would divorce after a year. The success of that hit led to appearances on The Ed Sullivan Show and won her prominent fans like James Baldwin and Langston Hughes, the latter calling her “strange” and “far out” in a paean published in the Chicago Defender.

At age twenty-eight, when her diary begins, Simone had an apartment on Central Park West, furnished with a baby-grand Steinway, and drove a steel-gray convertible Mercedes Benz 220 SE with a red leather interior and matching suitcases in the trunk. She had her crooked teeth capped in gleaming white. (She never smiled in her early publicity shots.) On sunny afternoons she drove to Greenwich Village to go shopping with her best friend, Kevin, a black female prostitute who had educated Simone in the ways of fashion and men. Simone’s nights were now spent in clubs, especially the Village Gate, an upscale jazz and folk venue fast becoming a hub for a cultural renaissance: Richard Pryor, Bill Cosby, and Woody Allen all performed there, opening for Nina Simone.

By 1961, however, with no new hits and her career sagging, Simone was having more trouble convincing club owners to book her, because of her confrontational style. What happened next would define her life and art in the 1960s: a chance meeting with an unlikely suitor named Andrew Stroud, a swaggering police detective from Harlem.

Stroud was about as powerful a black man as one could find in New York at the time. Having risen in the force after cracking a major jewel-theft case in 1954, he was notorious for taking bribes, beating up petty criminals, and consorting with the Mafia figures who ran the nightclubs. He cut a handsome, if roguish, profile. Light-skinned and barrel-chested, he had a pencil-thin mustache, wore tailored suits, and carried a .38 pistol, which he was not shy about brandishing.

In March 1961, at a New York supper club called the Roundtable, a mutual friend introduced Stroud to the lanky, exotic chanteuse, who slyly pinched a french fry from his dinner plate as they talked. Stroud drove her uptown to the Lenox Lounge, a hub for Harlem’s elite, and bought her drinks. A love affair ensued. Stroud recounts the first time he sat down next to Simone at her piano, hip to hip, shoulder to shoulder, in her apartment. She began playing “When I Fall in Love,” a hit made famous by Nat King Cole.

“It felt like I was sitting next to a furnace,” he remembers. “There was all this energy and quivering, and [when] she sang and got into the song, all this feeling came out, the heat and whatnot—I’ve never experienced anything like that before.”

For Stroud, a frustrated musician who had played jazz trumpet in the navy, Simone was a mysterious creature, his first introduction to the Greenwich Village renaissance, where racial and sexual barriers were fast melting away. Simone took him to her regular hangout, Trude Heller’s, a jazz club frequented by women Stroud describes as having short hair, large muscles, and wearing men’s pants.

Even as she dated men, Simone had an obvious affinity for assertive women and was also greatly beloved by gay men. Coming from a traditional Southern upbringing, she was ambivalent about gay identity her whole life, even though her greatest friends, like Baldwin and Hughes, were homosexual, as was her first devoted fan in Philadelphia, Ted Axelrod, a college student and clubgoer who introduced her to Billie Holiday and “I Loves You, Porgy.” Simone’s sexuality seems to have been fluid, and some former associates, like Al Schackman, insist Simone had female lovers, pointing to her relationship with Kevin. (Stroud says Simone supported Kevin with a fifty-dollar weekly allowance.)

The strange men and women who streamed in and out of Simone’s life threatened Stroud’s ego, even while he hid from her that he himself was married and had two sons (his wife had tried to scald him with a bucket of lye when she found Simone’s lipstick on a shirt). That summer, while dancing at the Palladium, Stroud, drunk on rum, accused Simone of sneaking away for a tryst and began beating her on the drive home. The beating continued on the street after they parked uptown. When Simone ran for a passing policeman, the man saw the higher-ranking Stroud and backed off. “I can’t help you, lady,” he said. The beating continued in her apartment, where Stroud aimed his gun at Simone’s face and threatened her life. (He claims there were no bullets in it.)

Some accounts have claimed Stroud raped Simone that night, but he denies it. In any case, Simone escaped to Schackman’s apartment, her face beaten and her eye swollen shut. “He hurt me bad,” she cried. “He hurt me bad.”

When Stroud saw Simone’s face several days later, he claimed not to remember what had happened, blaming the rum. But even as he asked for forgiveness, he also demanded Simone stop consorting with people he deemed intent on manipulating her (including her psychiatrist). “I got rid of the gay crowd and the hangabouts,” he says. “I made that part of the deal: you want to be serious, you want to be steady, you’ve got to be straight.”

From her letters, it’s clear she was deeply in love with Stroud, perhaps because he brought an iron-willed order to her mercurial emotional life and drifting career. In the summer of 1961, Simone was scheduled to play club dates in Philadelphia when she came down with an unspecified illness, thought to be meningitis. Stroud proposed marriage while she lay in the hospital bed. After saying yes, Simone spent the rest of her monthlong stay writing love letters. “Maybe it’s your eyes, Andy,” she wrote in July 1961. “I don’t know what it is, but I like giving to you.… I feel like you are a bottomless well that I can pour water into endlessly and it would never be all you needed or wanted… and you’re so gentle—you’re my gentle lion, my saint Bernard and sometimes my stud bull! (And sometimes bully).”

In another letter, she wrote, “I pray we’ll be together till death.”

MISSISSIPPI GODDAM

A psychiatrist told Nina Simone to make lists of all the good things in her life as a way of warding off depression. And so her diary opens with a description of the three-story house she and Stroud bought after getting married, in December 1961.

“The trees, green grass, all the little flowers, apple tree, cherry trees, the vacant spot where greens should be growing,” she wrote. “How about that, Nina! $50,000 worth of house. That’s really something. So much I’ll have to get used to—so many good things! I even got fountains in the yard that just need hooking up. Two cars: 1 nigger, 1 classy (paid for, too.) My own room that’s big enough for all my stuff and neat beside. And I don’t have to feel guilty about it and I don’t have to share it.”

From the start, Stroud saw Simone as his ticket to a better life. And Simone, though she hated performing every night, believed in his vision for her. If they had had money, she wrote in December 1962, “I’d be twice as free as I am now—And you know what that means, Daddy!: Pancakes in the morning, diet food in the P.M. and loving at night.”

That year, Stroud decided to retire early from the police force, firing Simone’s lawyer and taking over as her manager. A quick study, Stroud had learned the music business from famed jazz writer and record producer Nat Shapiro, whom he’d befriended while Simone played the Village Gate. Stroud drew up a new contract with nightclub owners promising Simone would forfeit her pay if she attacked the audience, which helped expand her bookings. But Simone wanted to escape the clubs altogether for classier venues. So to prove himself, Stroud promised to fulfill her childhood fantasy of starring at Carnegie Hall, ostensibly as the first black classical piano player to appear there. (They didn’t realize that Hazel Scott had already beaten her to it, in the 1940s.)

To pay for it, Stroud cashed out his police pension of six thousand dollars and used it to promote a performance at Carnegie Hall on April 12, 1963. It was recorded by Colpix, Simone’s record label, and released that same year. Though the album didn’t yield any hits, it shored up Simone’s optimism. On July 5, 1963, Simone wrote to Stroud: “Today (as I was playing the piano) it occurred to me how thankful I should be for all that I have—all of a sudden, I could see just over the hill and I knew that all my alleged big problems were going to be solved so soon now.”

But there was still the issue of Stroud’s regular beatings. “Those I can’t take,” she wrote in the same letter. “For some reason they destroy everything within me—my confidence, my warmth and my spirit! And when that happens I just feel that I must kill or be killed—you know how I just about lost my mind the last time.”

In late 1962, Simone had given birth to her only child, a daughter named Lisa Celeste. Stroud wouldn’t allow Simone to breastfeed the baby, telling her he was jealous. Perhaps inevitably, Simone began spending more time with a woman who would alter her worldview: Lorraine Hansberry, the activist and playwright who wrote A Raisin in the Sun and who authored “The Movement,” the handbook for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The two spent weekends together at Hansberry’s country home in Westchester County, outside Manhattan, talking for hours about black identity and revolutionary politics, which had held little interest for Simone in the past. “Lorraine carried her over into high gear, put her on fire,” Stroud says. After meeting Hansberry one afternoon, Simone asked him to help locate the basin that fed water to New York City. “Why?” he asked. Because, she declared, “We’ve got to go poison the reservoir!”

At the time, Stroud never suspected Simone of sleeping with Hansberry, and there’s no proof the two were lovers (Simone never records anything about gay affairs in her writings). Nikki Giovanni, the gay black poet and a close friend of Simone’s in the late ’60s, says, “What is important is that she loved her and she was loved in return. She never had to watch her back. With Andy, she watches her back.”

Her passion for politics was fully catalyzed by the murder of civil rights activist Medgar Evers on June 12, 1963, followed by the Mississippi church bombing that killed four black schoolgirls two months later. Ablaze with anger, she sat at her piano and wrote “Mississippi Goddam” in an afternoon. She recorded it in the spring of 1964, her first single on her new record label, Philips. The song was an immediate sensation with students and activists, but riled her traditional audience. A crate of records was mailed back to the label, each one broken in half.

Thus began Simone’s struggle to reconcile her musical career and her conscience as an activist. She immediately saw her audience divide after “Mississippi Goddam,” between supper-club regulars and the new crowd emerging on college campuses. The choice seemed literally to hurt Simone.

“I wish I could really consider it work and just do a job and not care,” she wrote in her diary in August 1964. “The truth is I’m not on the same circuit as the typical American audience. I can’t reach them unless I turn myself inside out! And sometimes it takes too much energy. And then I feel so hurt that they don’t get me. Maybe if I thought of myself as Lenny Bruce, it wouldn’t hurt so much.”

She concludes, “Maybe I’ll have to get so hard that I don’t care at all. Then there’ll be NO hope for me. And I don’t want to reach that point.”

That same month, after weeks of depression following the Village Gate shows that Shepard witnessed, Simone found a spark of determination to forge ahead. “I mustn’t stop,” she wrote. “There’s Dinah [Washington] + Billie [Holiday] who died without the world knowing what they said. Can the world know what I’m saying while I live? Maybe not the whole world, Nina, but most of it—I believe it. The world knows what the Beatles are saying—the kids do—I must save the older ones.

“And I must not start regretting what has passed,” she ends, after switching from pencil to blue pen. “Everything must be new.”

The music was both her wound and her salve. She complained constantly of being overbooked by Stroud, even while craving a radio hit and the money to maintain an upper-class lifestyle. A pragmatist, Stroud saw the “message” music as the problem, not the solution. Songs like “Pirate Jenny,” performed as harrowing threats and sometimes punctuated with curses, shocked crowds at Carnegie Hall. “She’d get to a certain part—‘Kill them now or kill them later?’—and people, families who brought their children, you’d see them leave,” says Schackman. “Kids were crying. Oh, they couldn’t take it.”

Stroud urged her to show her support through private donations to Martin Luther King’s organization and others. “I had promised to get her over and get her things she wanted,” says Stroud. “She wanted nice things—she wanted to move the house over and put in a swimming pool—and I said, Yeah, but you can’t get it with ‘Mississippi Goddam.’ I said, If you would listen, if you would go out there and stroke the audience, we could get on these big TV shows for exposure, into Vegas in some of the big rooms.”

And even as Simone reveled in her newfound sense of purpose, talking eloquently to reporters about her desire to “reflect the times” in her art, she grew bitter watching younger rivals like Aretha Franklin and Roberta Flack (who was imitating Simone’s style) get appearances on late-night talk shows, soaking up the fame that she felt was her due.

Her erratic moods caused her to throw herself at Stroud’s mercy one minute, rage against him the next. His prescriptions were limited. “Andy suggested pot every day for a while,” she wrote in her diary. Elsewhere she wrote: “Andrew told me whenever I get depressed I should have sex again right then and say ‘fuck it’ to the depression.”

Sex became her primary refuge. In her diary, she documented it obsessively, desperate for “the only thing that allows me to be an open and warm human being.” She connected sex directly to her music. “Yesterday,” she wrote in an undated entry, “I learned where the source of power is for my performances (the love songs are the best) so all my concentration is centered there, drawn out to a blunt statement about sex at the end.”

But Stroud, a man with limited patience and zero interest in psychology, often lashed out in frustration at her unpredictable temperament. Simone wrote on August 6, 1964: “Andrew hit me last night (swollen lip) of course it was what I need after so many days of depression. I wish I had someplace to go (I wish I had some hope). All the motherfucker did was get me off him; it still leaves me with the same fucking problem—he actually thinks I want to be hit (he told me so). He believes like old-fashioned black men that I need beating up once in a while. The fool believes I like it—there are milder forms of discipline.” (Stroud is hardly contrite: “I’m the type of guy, I don’t take any shit off of anybody.”)

Four days later, in another letter to Stroud, Simone explained that she had a compulsion toward violence herself, one ultimately driven by her own career, which seemed to sap her of life:

“I must hurt someone—I can’t help it—I’m also pushed too far. The value of a psychiatrist was he was paid to take my shit.… I didn’t need him for the reasons I thought but work most of the time is like a deadly poison seeping into my brain, undoing all the progress I’ve made, causing me not to see the sun in the daytime, not to smile, not to want to get dressed, not to care about anything except death—and death to my childish mind is simply escaping into the unconscious.”

During this period, Stroud checked Simone into Columbia Presbyterian Hospital for testing, trying to diagnose her depression. According to Stroud, “They had conducted every known test on the books at the time and had not been able to pinpoint anything.” (In the late 1970s she would begin lithium treatment.)

In the fall of 1964, Simone recorded a dream, with images that suggest her underlying struggle: “I lost my way, looking for a flash light, next thing I know, there are animals—first a bear, then slightly familiar creature like a puma, a skunk and the one which attacked me was like a miniature giraffe, but wild and heavier—it was tearing into my arms as I awakened.”

That winter, she cracked the Billboard charts for the first time since 1959 with “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood,” written by professional songsmiths for her album.

I PUT A SPELL ON YOU

In January of 1965, Lorraine Hansberry died following a long battle with cancer. After the funeral, a numb Simone wrote a sparse entry in her diary: “She’s gone from me and I’m sure it’ll take like many years to accept this thing. It’s so far out.”

The next day, she and Stroud departed for a Caribbean cruise. Simone was despondent. “The rocking + rolling of the ship almost made me scream with pain,” she wrote. “The thought of suicide returned briefly—I felt so hemmed in—didn’t sleep at all—hated Andy + everyone—it occurred to me in my pain what Gerry [her psychiatrist in Philadelphia in the late 1950s] said years ago, ‘I can’t take disappointment.’”

She groped for answers: “I stole a book about psychic power which could be of tremendous use if I’d use it seriously,” she wrote. “Perhaps I shall.”

Her next single, recorded that same month and released in June 1965, would be a cover of Screamin’ Jay Hawkins’s “I Put a Spell on You.”

The year 1965, says Stroud, marked an existential turning point for Simone, when she began regularly talking of suicide. “I can’t beat the poverty, the inferiority complex, the sex and show business,” she wrote from an unidentified dressing room. “It’s like I came here whole and slowly through the years, I’ve wasted away to almost nothing—pretend you’re happy when you’re blue—pieces taken out of me hunk by hunk, slowly but surely—paying for whatever help I got with my blood—doing anything to be accepted (anything) and the tragedy of not being accepted after all—not accepting myself—I can’t stand to look at myself in the mirror anymore—I can’t stand the sight.

“But then,” she concludes, “why haven’t I killed myself?”

That spring, Simone had canceled a series of dates at the Village Gate to attend the civil rights march in Montgomery, Alabama, led by Martin Luther King Jr. On March 24, she had performed on a stage propped up by caskets donated by several local black-owned funeral homes, mingling with the likes of Mike Nichols and Elaine May, Dick Gregory, and Sammy Davis Jr. That evening, Simone met King for the first time. According to Al Schackman, Simone reached out her hand to King as he approached and loudly declared, “I’m not nonviolent!” King, momentarily taken aback, said gently, “Not to worry, sister.” Simone softened, put out her hand and purred, “I’m so glad to meet you.”

She was moved by the event, but Stroud wasn’t, sensing Simone’s commercial prospects dimming. Afterward, they went home to Mount Vernon and fought bitterly. In a fit of rage, Simone demanded sex from Stroud, as she often did, this time reveling in a new feeling of liberation from the “old fashioned black male.” When Stroud rejected her advances, she wrote, “I lost complete control of myself and let loose with anger that had me screaming out the window, shrieking. I felt the freedom of anger—in complete confidence. I put on my diaphragm and told myself that I was going down to the house [from the guest house where she had retreated] and would kill him if he didn’t appear—he appeared—we had a lovely time and fell asleep exhausted.”

Even as she fought him, Simone constantly looked to Stroud for assurance. Some higher success was always out of reach. In 1964 and ’65, she recorded the songs for Let It All Out, a commercial pop album that would emphasize romantic standards over protest music, including two songs written by Stroud himself. In the spring of 1965, Simone wrote, “Andy just informed me while I’m feeling sorry for myself in not having a hit record I should remember: the Supremes, the Impressions, Gale Garnett, even Peter Seeger—(these people make 1⁄2 what I do a night!), so even though I don’t have hits, I command fees and respect that these other folks don’t.”

In July, Simone went on her first European tour, something she’d longed to do. It was a revelation. For the first time, Simone saw rock groups mimicking black music, including the Animals and the Rolling Stones. “All the music is negro,” she wrote to her brother Sam Waymon on July 15. “We’re bringing back an album of some kids who sound very negro. And one night the Animals (the rock + roll group that recorded my “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood”) took us to a dance hall that was just like all the old swinging negro halls where they danced… all the old dances that we used to do plus the new ones these kids do…. We’re treated so beautifully here.”

Simone was a sensation in Paris, too, where she was lauded by French singing star Jacques Brel for her interpretation of his hit “Ne Me Quitte Pas,” which she had recorded the previous January. Afterward, Simone made a list of things she wanted to accomplish when she returned to the United States, penned on Air France letterhead. It fairly sums up Nina Simone in 1965: “Take French lessons, go swimming a lot, buy Langston Hughes books, get high, hire a girl once a week to take care of your clothes (sew, clean, organize closets) find a psychiatrist, a Spanish baby sitter, take dancing, find shoemaker, write Hazel Scott, find yellow pills, buy books [a photographer friend] told me about—stop abusing Andrew (think of surprises for him).”

NE ME QUITTE PAS

In 1966, a dam was about to burst in Nina Simone’s marriage and in her art.

“Last night Andrew talked of my possible suicide,” she wrote on January 20. “He let me know that he would not only not suffer, but, he would be relieved. I hate him—

I have every intention of leaving him, if I live, and making him suffer in ways he hasn’t ever dreamed of. I hate him.”

That same month, Simone sent Stroud a Western Union telegram: “Everything is going to be fine.… 1966 is still our year.… I love you, Nina.”

Simone couldn’t square her constant yearning for personal and musical freedom with her need for stability and regular income. In an undated note from 1966 titled “Remember, Nina!” Simone urges herself to push into more explicitly black music, but only as far as white audiences will allow. “With every new turn of events in colored people’s favor, you get

a little looser—don’t be afraid to go all the way ‘colored’ if they’re ready—take your time starting—enjoy yourself! The white folks are condoning revenge now—remember ‘Nevada Smith’?” (In the 1966 Steve McQueen western, the white son of a Native American avenges his father’s death.)

That year, Simone recorded “Four Women,” one of her few self-penned songs, a searing portrait of voiceless women struggling against poverty and victimization (“My skin is brown, my manner is tough / I’ll kill the first mother I see”). Like much of her late-’60s material—such as “To Be Young, Gifted and Black,” inspired by an unfinished Hansberry play—the song sought to define black consciousness, and gave her credibility with black youth. But Stroud, along with Philips record executives, continued to push Simone toward mainstream material, too. And, ironically, she recorded some of her most enduring ballads that year, like “Lilac Wine” and “Wild Is the Wind.” In many ways, the intensity with which she imbued these songs was more telling of her inner life than her protest songs were.

Like a leaf clings

To a tree

Oh my darling,

Cling to me

For we’re creatures of the wind

And wild is the wind

So wild is the wind

By now, her reputation as a belligerent performer had eroded her standing among critics. Prominent activists like Harry Belafonte avoided her. As a review in Life magazine would later put it, “She still pollutes the atmosphere with a hostility that owes less to her color than to the rasping edge on her pride.”

Stroud treated Simone like a volatile product to be managed. She battered him weekly with emotional meltdowns. He describes mornings when he would wake up and Simone would be sitting up, arms folded, glaring into the distance, coiled to fight him. She left little notes to Stroud using black Magic Marker: “One day, when I’m not so tired, I’ll kill you.”

By 1967, the year she sang “I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to Be Free,” Simone’s activist persona was becoming more fierce and confident, but privately she was still filled with self-loathing. She complained bitterly about her image on her mid-’60s albums (a wide, toothy grin and a straightened, Kennedy-era bob: a photo negative of Doris Day) and kept a picture of herself in her wallet “to remind me of how I never want to look.” In letters, she rails against “amateur” photographers sent by Ebony and Look who she felt made her ugly and caused her “shame.” In December, in a note to herself, she mentions the launch of her and Stroud’s new record company, called Ninandy, but she has no hope for the future.

“Everything I’ve had in terms of security (especially my music) seems to be slipping right between my fingers,” she wrote. “I haven’t been needed for a while. Nowhere in the press am I mentioned, voluntarily. Am I evolving again??? What is left for me now?”

For every battle Simone waged with her depression, however, a rawer, freer personality emerged: wearing African beads in her hair, she could now perform a sultry dance onstage and give impromptu lectures on black identity, casting herself as a messenger, the “high priestess of soul.” Black people were a “lost race,” she told an interviewer, according to Simone’s recent biography, and her songs were meant to “provoke this feeling of who am I, where do I come from, you know? Do I really like me, and why do I like me?”

That year, while she was playing in Oakland, California, Stroud says he discovered Simone having an affair with the new dashiki-wearing guitarist in her band. Stroud confronted her, and they finally agreed to have an open marriage, their relationship strictly a business arrangement in which Stroud managed her career. “I knew all along that she was having these relationships with both men and women,” claims Stroud, who also had several affairs.

In August 1969, Simone went on a monthlong vacation to Barbados. “It’s nice to feel like a queen down here, be the most beautiful, and envied by all the women,” she wrote to Stroud. “Money made these feelings possible—so Andrew, I thank you for teaching me this—though I’ll probably forget it the moment I get back to HELL.”

Hell, she stated plainly, was the United States. And not long after, upon leaving Stroud for good, she left America, too, the start of her years drifting around Africa, Europe, and the Caribbean, aided and undermined by a series of opportunistic handlers, sycophants, and wealthy patrons. Having finally gained her freedom, she was left alone to the merciless weather of her own moods, becoming a bizarre and sometimes embarrassing spectacle in concert—often riveting, occasionally miraculous, but also unhinged and frightening. She tried several comebacks, but none succeeded. Her musical output withered as she became a heavier drinker, periodically entering mental hospitals. By the time of her death, in 2003, Nina Simone had almost faded from American cultural memory, a cult figure living out her final years in the French Mediterranean.

The last page of her diary—undated, but likely from the late ’60s—foreshadowed what was to come: “I learned that my pain (no matter how great) is a private matter (my hell is my own) and I must not tell it to any one else—there are no people who can help me.” For Nina Simone, hell was not just a country, but a lifelong burden.