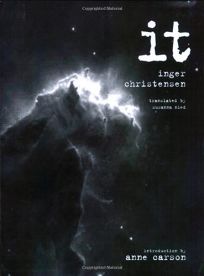

Plato is disingenuous when he infamously has Socrates pit poetry against philosophy in Book Ten of The Republic. He aspired to be a verse-dramatist before becoming a philosophical one and was familiar with the work of Hesiod, the ancient philosopher-poet whose work stands with Homeric tradition at the origins of Western poetry. In introducing Susanna Nied’s stunning translation of Danish poet Inger Christensen’s it, Anne Carson recalls Hesiod and the tradition of philosophical poetry, saying: “Inger Christensen combines Hesiod’s purposes into one pronoun.”

Hesiod’s poems do not ignore the Homeric subjects of war, passion, and history, but his titles look to more intimate processes: The Birth of the Gods, Works and Days. These poems are fundamentally somatic, poems of the body (human and divine), of the relationship between the body and the universe; poems of birth, school, worship, work, death; poems of life’s significant blip as part of the universe. This indelible sense that life matters is the “it” of Christensen’s long philosophical poem. At it’s heart is a view of human life interwoven into galactic, social, sexual, economic, and linguistic experience. it is both a brilliant philosophical reflection on the forces (biological, physical, political) that organize life, and an equally brilliant poetic invocation of the drives (emotional, sexual, subjective), so much a part of living.

it begins with a prose-poem rendering of the big bang, a signal of the scope of Christensen’s ambitions. The self-arranging universe is a force of grammar and metabolism: “Turn / after turn is rephrased. Gains structure in its ceaseless search for / structure. Variations inside fed on matter from outside.” Eventually this organization becomes social (“The city is a labyrinth”), then domestic (“They wait in the bedroom, living room, entry, kitchen, outhouse”), and finally private (“Someone is alone because he has been able to imagine something else”). The first part of it funnels its vision from the birth of the universe to the death of an individual, setting up the poem’s profoundly humanist vision, one comparable to a verse rendition of Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man.

If this sounds pretty abstract, it is. The opening and closing sections are unabashedly abstract poetic statements of philosophy relating body to world. This reliance on abstraction derives from the moment of the poem’s original publication, in 1969: Christensen speaks from a world on the verge of deconstruction. Today this world is being historicized, and abstraction is a bad word because it smacks of the pretensions of postmodernism. The poem’s powerful middle section, “Logos,” however, avers abstractions from firm ground, what the poet calls “traumatic chemistry / political consciousness / internal sexuality of words.” Fittingly, the images here range from those that figure geopolitics as a disturbing, sadomasochistic encounter with America (“He thinks the entire machine’s being run / by the sexual mystique of the struggle for might”) to those that figure as links rather than fissures between the life of the body and of the mind (“Our life together / is a sexual and therefore mental / or is a mental and therefore sexual / activity my love!”).

Inger Christensen inspires awe in supple figures of bodily experience, and of social and sexual interaction. The firm ground of metaphysics in it is always the human form, and in this way the poem reminds us all that philosophical abstraction and metaphysics aim to clarify experience, not cloud it; clear things up, not bog us down.