Every year, more than a hundred million monarch butterflies in the U.S. and Canada go south for the winter, flying more than ninety miles a day for up to 3,000 miles. Monarchs living west of the Rockies aim for Baja California, while those living east of the Rockies head for the mountains five hours northwest of Mexico City. The monarchs are able to biosynthesize magnetite from their diet of milkweed, enabling them to fly at night using magnetic fields as a compass. Ever since he read about the migration in National Geographic ten years ago, Portland-based filmmaker Dennis Fitzgerald wanted to shoot a music video with the butterflies as a backdrop, but he wasn’t about to squander such a magical sight on any old song. Like a patient Prince Charming, he waited for a song that fit.

That song was The Shins’ “Saint Simon,” the fifth track on the band’s second album, Chutes Too Narrow.

Fitzgerald had directed the video for another Shins song, “Kissing the Lipless,” the year before; he and lead singer James Mercer were friends who worked well together. Though they had a shared vision for “Saint Simon,” coordinating the schedule of the band and the butterflies proved challenging, and a year went by before SubPop, The Shins’ label, gave the green light. But once they did, they offered to both pay for the video and surrender artistic control to Fitzgerald.

In February 2005 the band and crew headed south. There were epic nights of battling mariachi bands, tequila-tinged exchanges with new and old friends, and challenges with a two-handled wooden box containing a car battery that one tries to keep hold of as the level of voltage is turned ever higher. The contraption was named El Diablo, though Mercer, who held out longer than most, called it “Shock Your Drunk Ass—40 pesos.”

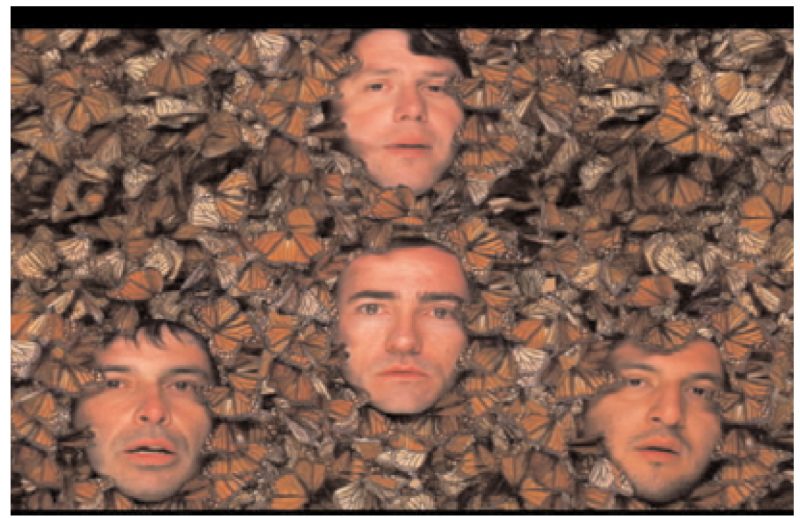

But El Rosario de las Mariposas, the privately owned butterfly reserve where they filmed the video for “Saint Simon,” was without question the heart of the trip. The Shins sang and played while hundreds of thousands of orange and black butterflies filled the air around them. The monarchs carpeted the ground and obscured the trees, making it nearly impossible to walk without stepping on dead or dying monarchs, nearly a foot thick in places. Parts of the reserve are highly restricted, accessible only to scientists and researchers. Fitzgerald and The Shins were able to access these parts due to the generosity—and, perhaps, foresight—of the head of Fitzgerald’s Mexican production company. When the producer went scouting, hoping to obtain permission to bring gear into the historic Rosario de las Mariposas, he met and bonded with the jefe of the reserve. The jefe revealed that his brother was in jail in Mexico City, so the producer bailed him out. The jefe repaid the debt by allowing the band and film crew to bring cranes, instruments, and equipment into fragile areas, though scientists accompanied them at all times. Although the band members appear to be playing and singing amidst all the butterflies, in fact they were “very quiet and very respectful,” said Mercer. They sang under their breath, so as not to disturb the butterflies, who he imagined were completely exhausted after their incredible journey.

Indeed, only half of the butterflies that attempt the trip reach their destination. Though the migration usually takes four to five generations to complete, the butterflies return to the same reserve, to the very same Oyamel fir trees, year after year.

Being surrounded by such wondrous creatures left the band and crew completely in awe. “It’s one of the things you should see before you die, definitely,” said Fitzgerald, who ranked the filmmaking experience as his favorite, though he’d just come from filming a documentary in the Himalayas.

“We were all changed in one way or another,” said Mercer.