On a Monday morning in early June, Nicole Storm arrived at the Creative Growth Art Center in downtown Oakland, California. Light poured in through broad windows that faced the street. Nicole put her jacket and lunch away in the closet and then selected a large piece of cardboard from a stack in a hallway. A staff member helped her secure the makeshift canvas to an easel and set out her paints and markers. She chatted with some fellow artists and then explained to me that she is starting a new project, after having finished a few paintings last week. Nicole refers to her artistic process as “taking notes.” It is a way for her to organize the events of a day, although the results never look like a typical archive or journal. She creates bright washes of color that provide a glowing background for lines and shapes that appear like an indeterminate form of writing. Nicole records what is going on around her with marks that may initially seem impulsive and spontaneous. But they are the culmination of a well-honed practice, undeniable creativity, and decades of sustained work.

Nicole was born in 1967, during what her mother, Diane, refers to as “the tail end of the Dark Ages,” when someone like Nicole, who has Down syndrome, would almost certainly have lived her entire life in an institution. At that time, Diane recalls, “I sent away for some information about Down syndrome and what I got was bleak. The life expectancy was twelve years. Fifty percent of people were dead before their fifth birthday. So I threw that stuff in the trash and decided to do it my way.”

Diane and Nicole are closer than most mothers and their adult daughters. They live together, and Diane volunteers once a week at Creative Growth when Nicole is there. Nicole inherited Diane’s round face and direct stare. They both speak with a great deal of confidence. Diane attributes Nicole’s confidence to how she “ran with the pack” as a kid; she was thrown into the deep end of progressive schools that included her with the rest of the students. Diane’s confidence developed out of her fierce advocacy for Nicole and a lifetime of fighting with bureaucratic systems that did little more than tell her what her daughter would not be able to do. I mentioned to Diane that my daughter, like Nicole, has Down syndrome. “You know how it goes then,” she said. “We had no support when she was growing up, but I’m sure your daughter has a bright future.”

Diane is right. My daughter is part of a generation with more opportunities to attend school with her peers, although she still faces plenty of challenges. I hope she might be able to find a job and work in a supportive community. But historically our society has expected very little of people with intellectual disabilities, which makes Nicole’s success as an artist all the more remarkable.

When Nicole was in her twenties, Diane searched for a day program that Nicole could attend while she worked full-time. But they struggled to find a suitable situation that met Nicole’s need for routine and predictability. She spent most of her days on public transportation. Diane recalled a time when Nicole traveled with a group to an event at a library in Berkeley, only to have to catch another bus fifteen minutes later to come back home. Eventually Nicole moved into a group home for people with disabilities, where she lived in an apartment with the help of support staff. Both Nicole and Diane believed this was the independence Nicole deserved. But after two and a half years, she wasn’t thriving. Nicole wasn’t developing much of a life outside her apartment, and the support staff wasn’t as attentive as Diane had expected. After Nicole became seriously ill with pneumonia, they decided they had had enough. Nicole went back to living with Diane. An artist friend told them about Creative Growth, and Nicole started attending the program regularly. The new sense of routine and purpose transformed her almost overnight.

“It was the most wonderful moment,” Nicole remembered.

“You’re right,” said Diane. “That’s when the magic started to happen.”

There are a range of ways to describe what Creative Growth is. It is a twelve-thousand-square-foot art studio in a building that was once an auto-repair shop. It is a space where artists come to work on projects and prepare for upcoming exhibitions. It is a place of artistic pursuit, but it is also a provider through the Regional Center of the East Bay, and serves people who have historically not been given the chance to express themselves or to be part of a community. Creative Growth is a nonprofit organization and its mission is to advance the mainstream inclusion of artists with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

Most day programs for people with disabilities include crafts because it is assumed those activities are difficult to get wrong. These programs exemplify the way people with disabilities are treated like children: by comparing their work to grade school projects. This is emphatically not what Creative Growth does, and it has fought for the recognition of those who make art in its studio as serious artists. It was the first of hundreds of art studios that now serve people with disabilities in the United States, and the importance of its mission has gradually been recognized. Earlier this year, SFMOMA marked Creative Growth’s fiftieth anniversary with a major exhibition of 113 works, and paid $578,000 to bring many of the pieces into its permanent collection. It was touted as the largest acquisition of work by artists with disabilities by an American museum.

What is easily overlooked in this achievement is Creative Growth’s equally remarkable but far less glitzy daily operations, which serve about 140 artists per week. Many—including Nicole—never thought of themselves as artists before they enrolled. At the time of my visit, it had a six-month waiting list for services, and there were usually about seventy artists there each day. But I didn’t do an exact head count, and I wasn’t always able to identify who was an artist enrolled in its studio program and who was there as a staff member or volunteer.

I came to Creative Growth with questions about creativity—where we think it comes from and how we find value in it. I was interested in how the art world has historically positioned artists with disabilities as “outsiders” and whether the boundary that used to separate them from “insiders” was still maintained. But my interest in creativity and value was also personal.

My daughter likes to make linocuts. She carves a design into the rubbery surface of the plate with a small tool, presses a piece of paper against the plate’s inked surface, and then gives the resulting print to family and friends. As I watched artists at Creative Growth delight in the liquid gooeyness of paint, I recalled the wet sound of the ink as she rolls it into the grooves of the plate. I thought about how much my daughter would love it here—the materials, the camaraderie, the undirected time free of demands for productivity and proficiency. Eventually I began to think, Who wouldn’t want to be here? The place exuded an aura of radical acceptance and deep support. I wondered about my daughter’s future as an artist and how her work would be valued, even if being an artist is not considered a normal kind of work.

When it began, in 1972, Creative Growth responded to a profound shift in public policy regarding people with disabilities. Five years earlier, then California governor Ronald Reagan signed the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act, which sought to end the indefinite and involuntary commitment of people with mental health disorders in the state. Florence Ludins-Katz, an artist and teacher, and her husband, Elias Katz, a psychologist and the chair of the Art and Disability Program at the University of California, Berkeley, founded the center in response to Reagan’s plan. There was a growing consensus that community-based support was a more humane way of caring for people who had persistently been treated like outsiders than institutionalizing them. But there was no infrastructure in place for integrating people who had lived for decades in an institution back into mainstream American society. Without support, those who had been institutionalized were at risk of ending up homeless or in prison. As Nicole experienced, living options that appropriately balanced independence with support were difficult to find. In 1968 and 1970, Elias Katz published two manuals, The Retarded Adult in the Community and The Retarded Adult at Home: A Guide for Parents. The titles alone suggest that reintroducing people to both their families and a society where they have been told they do not belong might be disastrous if not done carefully. Elias and Florence understood that those who were transitioning from a life in an institution to a community-based setting needed to find new routines that provided social interaction and a chance for self-expression, and they sought to tackle the problem in a deeply pragmatic and person-centered way. With Creative Growth, the Katzes proposed to establish this pathway through artistry.

According to Tom di Maria, Creative Growth’s executive director since 2000, the Katzes were hippies influenced by the pop psychology and the mind-expanding impulses of the Bay Area counterculture. They started Creative Growth in the garage of their East Bay home when disability-rights activists in Berkeley, such as Judith Heumann and Ed Roberts, were fighting for access to basic public services like curb cuts and accessible public transportation. Heumann, Roberts, and the Katzes all drew inspiration from the larger civil rights protests of the time, but some of the leaders of those movements kept activists who were demanding disability rights at arm’s length. “When I told them we were all fighting the same civil rights battle, they didn’t believe me,” said Roberts, a polio survivor who founded the Center for Independent Living in Berkeley. “They didn’t understand our similarities. I did. Even now, many people don’t realize it.” The Katzes saw access to creative opportunities as a civil right, but they must have faced similar doubts about whether people with intellectual disabilities could even claim a right to human dignity.

The Katzes’ mission was to establish artistic creativity as a form of communication, and they identified the need for art studios to serve as centers of open exploration. Over the course of ten years, the Katzes opened three studios: Creative Growth Art Center, which eventually moved to its present location in Oakland; NIAD (Nurturing Independence through Artistic Development) in nearby Richmond; and Creativity Explored in San Francisco.

All three centers provide an environment where artists with intellectual disabilities could work at their own pace. Without offering any formalized classes, instruction, or therapy, staff members act as facilitators and advisers when needed. The purpose of the studio experience is not to improve the skills of the artists, but to foster their innate creative potential.

“Creative self-expression is the outward manifestation in an art form of what one feels internally,” the Katzes declare in Art and Disabilities: Establishing the Creative Art Center for People with Disabilities, their 1990 book that reads like part disability-rights manifesto and part manual for replicating their centers throughout the country. They emphasize that a nurturing and nondirective environment promotes growth and self-confidence. “The Creative Art Center sees each person, no matter how disabled mentally, physically, or emotionally, as a potential artist.” To the Katzes, creativity endures in an individual, no matter the circumstances. “Does a person who is disabled, who has been deprived, who has never had the opportunity to express himself still retain the essence of creativity?” they ask. They compare the creative expression of artists in their studio to the “surge of flood water when the dam has been removed.”

Art and Disabilities is a record of the Katzes’ determination to expand creative opportunities for people with intellectual disabilities, but it also captures their devotion to the individuals they worked with. Their treatise is filled with firsthand accounts of artists like George, a man in his sixties who had spent most of his life in a state institution. When that institution closed, George started coming to Creative Growth because there was no other community program available. “He is blind in one eye, has a large tumor in his neck, shuffles when he walks, and seems completely disconnected from the world,” they write. George struggled to communicate verbally, but the Katzes describe the rapid development of his art, from a few dabs of paint to canvases with brightly colored squares and rectangles. They clearly took pride in the artists they worked with. “Recently George’s work… was singled out by a gallery owner as being among the most promising,” they say, celebrating the recognition of human creativity as much as George’s individual efforts.

At Creative Growth I met an artist named Joe Spears who was making a collage, gluing pieces of a painting he’d made and cut up onto pieces of blue paper. A staff member helped Joe get the glue onto the paper, but she was careful not to intervene in the artwork without Joe’s permission or guidance. She asked questions but avoided making any decisions for him. She told me, “Joe likes the process,” an acknowledgment that the tactile stickiness and arrangement of shapes might be what draw Joe to make art. Emma, an artist who had been coming to Creative Growth for only a few weeks, liked watching Joe work. In another part of the studio, a staff member began to sing and play a ukulele.

Making art can appear to be a slow and impenetrable practice, and the time I spent at Creative Growth sitting and watching often felt unproductive, like I was at a party where I was desperately trying to make friends. I hovered over one table with people I’d just met. Then I noticed a woman weaving in another part of the studio and wandered over. I watched her work a piece of thick crimson yarn back and forth through the warp, deftly coordinating the moving parts of a loom that had been jury-rigged for wheelchair users so the foot pedals could be operated by hand. After several days, I mentioned to di Maria that my time there felt undirected. “Well, that’s what we do here,” he replied. “We are all about non-direction.”

Di Maria, a small-framed man, floated from one end of the studio to the other, checking in with artists and staff members. Over the last quarter century, he has been a tireless promoter of the artistic and commercial value of Creative Growth. But he also cultivates a studio environment that supports many other reasons for being at the center.

I tried to embrace di Maria’s idea of non-direction and to let go of the idea of productivity. While many of the artists there think of themselves as ambitious, even successful, some seem less self-conscious about their practice. “Everyone defines success differently here,” di Maria told me. Every artist is given the opportunity to exhibit their work, either in the center’s gallery space or in national or international exhibitions. And while some of their work has sold for tens of thousands of dollars and found its way into the collections of major museums, many artists are not focused on gaining success in the gallery system at all.

The Katzes thought success depended, in part, on an artist’s ability to communicate something about the human experience. They begin Art and Disabilities with an epigraph, a famous quote from the abstract expressionist painter Jackson Pollock: “When I am in my painting I am not aware of what I am doing. It is only after a sort of ‘get acquainted’ period that I see what I have been about.” The quote supports the Katzes’ claim that art expresses something universal about the human condition, something beyond the immediate control of the individual artist. It also demonstrates that this principle was already an accepted mantra of the art world by the time the Katzes started Creative Growth. The gestural, impulsive marks of Pollock and others had long been established as examples of creativity in its purest form. But claims to universal expression have also faced their share of skepticism. When I was a college student in the late 1990s, I learned that Pollock was an important artist even if his claims of losing conscious control over his work struck me as ridiculous. Was there really such a thing as a universal human condition? And if so, was it possible to find a satisfying way of expressing it artistically? What could Jackson Pollock’s creativity have in common with the experience of Creative Growth artists? Now I wonder why the Katzes needed to invoke Pollock’s lofty ambitions to legitimize the work of artists at Creative Growth, as if the mere opportunity to define their own version of success, which had been systemically denied to so many of them by our ableist world, wasn’t enough to give their practice value.

The act of making art often stands apart from the efficiency, speed, and productivity that modern life demands and that people with disabilities can find challenging to navigate. But do they have privileged access to creative inspiration? The art critic Roger Cardinal, who published Outsider Art in 1972, believed they do. Cardinal’s thesis is that human creativity is most evident when social and cultural conventions are disregarded. Creativity is “genuinely primitive,” Cardinal claims. “It emerges from the chaotic realm of undifferentiation, being released at the near-instinctual or primary levels of creation.” True art, according to Cardinal, is created by untrained artists “whose position in society was often obscure and humble.” Cardinal devises a demeaning trifecta of affinity between art made by colonized people (mainly Africans and Indigenous Americans), art made by children, and the art of the mentally ill. To Cardinal, all three groups exemplify an untrained hand and prerational mind.

Cardinal’s Outsider Art casts those with intellectual differences as a radical version of the troubled Romantic genius, free of all convention and cultural influence. True creativity, he believed, comes from the inner drives of people who are outsiders, uninitiated in social norms and artistic conventions. But, according to Cardinal, the artist and the outsider aren’t exactly creative equals. Artists seek the spiritual meaning and mark-making that seem to come easily to those on the cultural periphery. In the history of art, it is not the outsiders that get recognition. It is the insiders—Paul Gauguin, Paul Klee, Jackson Pollock—who turn the creativity of the outsiders into a proper style.

There is a big difference between the outsider artist and how the Katzes saw the artists in their studios. The Katzes centered the creative potential of artists with disabilities and responded to their social and individual needs. Cardinal’s framing of the outsider artist is more of a backhanded compliment, celebrating the mysterious depth of the art while showing little concern for the well-being and resources of those who create it. And he isn’t focused only on those with intellectual disabilities or mental illnesses. An outsider artist can refer to someone who is self-taught, a folk artist, or anyone whose creativity doesn’t fit the mold of MFA studio programs. These days the term outsider artist usually appears in exhibition catalogs and reviews in scare quotes, to acknowledge a discomfort with the cliquish boundaries the term defines, while admitting that there’s still something useful and familiar about its meaning.

There is a persistent belief that art expresses a universal human experience, that art embodies an instinctual urge to make a mark, whether that mark is drawn by Pollock, a person with schizophrenia, or a three-year-old child. I have noticed certain words and phrases used repeatedly by gallerists, art dealers, and collectors to adulate the outsider art they support: powerful, on the edge of contemporary art, mysterious, raw, impulsive. I have asked them to clarify what they mean by these terms, but their attempts to elaborate have never really satisfied me. As an art historian, I have been trained to be skeptical of these descriptions and to recognize how they traffic in clichés of emotional subjectivity and suspect pathways to an inner self. They have always sounded lazy to me. Art that can be anything or be made by anyone isn’t strong enough to create any focused meaning on its own. And how can we know what is being expressed, if it is couched in opacity, something we can never truly understand? What can a work of art tell us about our world, if the best we can do is celebrate its mystery? Although describing art as “mysterious” might give it value to insiders, it does little to address how people with disabilities have historically been treated as outsiders, or whether those conditions might change. In other words, maybe the connection between disability and creativity is easier to cultivate, while connections to other parts of the world through employment, community, or civic action are much harder to establish.

The Katzes designed Creative Growth, in part, as a way to convince the public that people with disabilities could be skilled artists with commercial potential. “To come to the Art Center,” they write, “to see the seriousness and intensity of the students as they are involved in creating art is a revelation to all who visit.” The Katzes believed that Creative Growth might change the public’s perceptions about people with intellectual disabilities. And given the profoundly low expectations at the time, it is easy to see why they identified this purpose, even if now the goal might feel uncomfortable, as if people with disabilities are required to prove their human worth to a nondisabled audience.

The Katzes cite many reasons to have a commercial gallery space attached to their art centers. “The money is a welcome addition to the praise of a job well done,” they write. “The Art Center takes pride in the recognition that the art of persons with disabilities is much sought after and has value to society.” Creative Growth has benefitted from the fact that the idea of outsider art has become, paradoxically, the way in which the art of marginalized people is given commercial value. At first, the field of outsider art was driven by collectors who saw it as whimsical and intriguing. It eventually moved to galleries and art exhibitions. Today, outsider art straddles the high-end art market and grassroots community. The Outsider Art Fair has run annually in New York since 1993. Another ran in Paris from 2013 to 2022. Many Creative Growth artists have found audiences for their work in these venues. But it is often difficult to match their art with what the market expects of artists with disabilities. I’ve talked to gallerists about how art buyers often have specific ideas about what outsider art looks like, although artists don’t necessarily feel compelled to meet those expectations. “Artists who do portraits or landscapes are easier to place in art fairs and expos,” one gallerist told me. “Artists who work from Disney models are harder. There are copyright issues.”

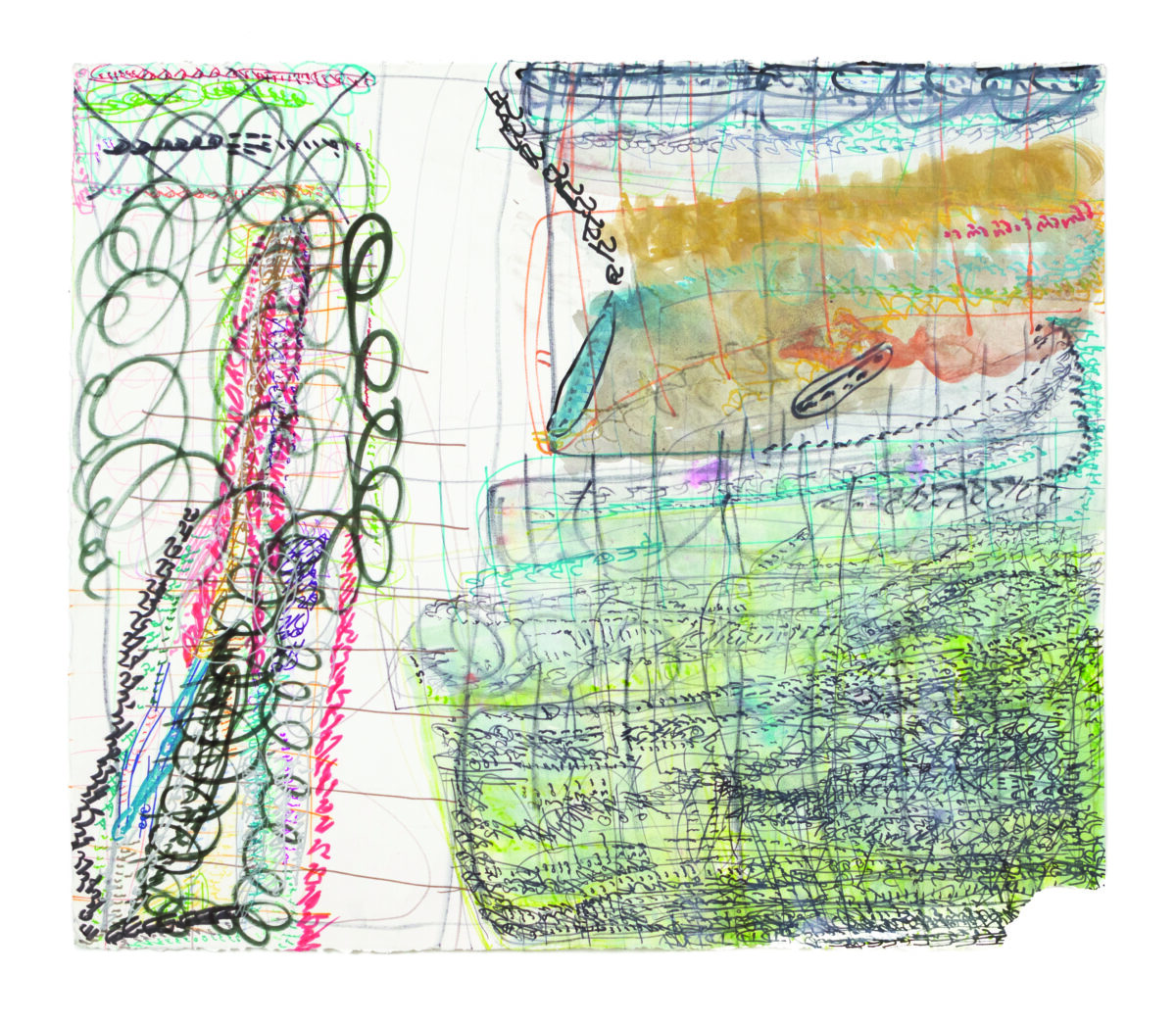

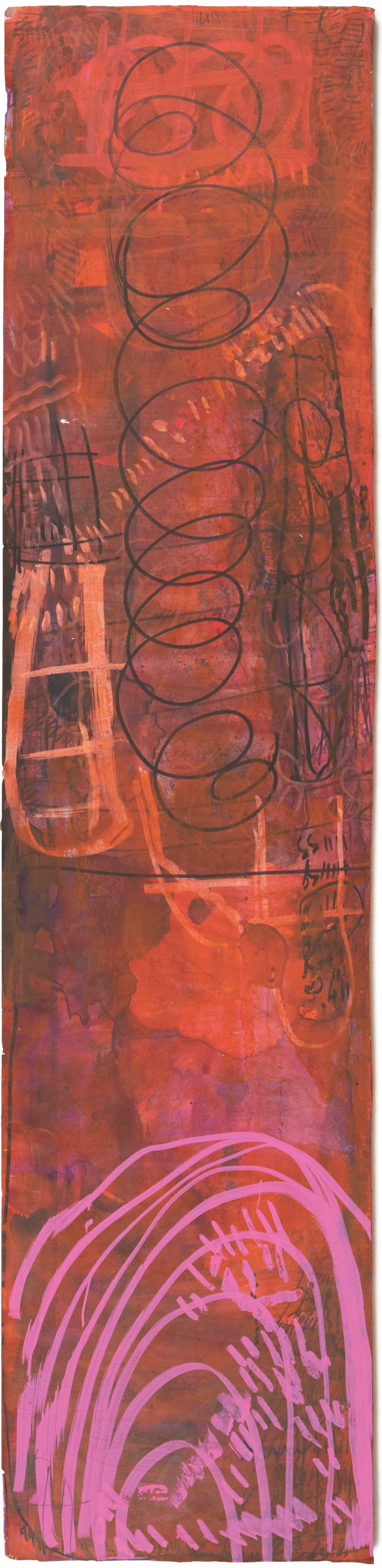

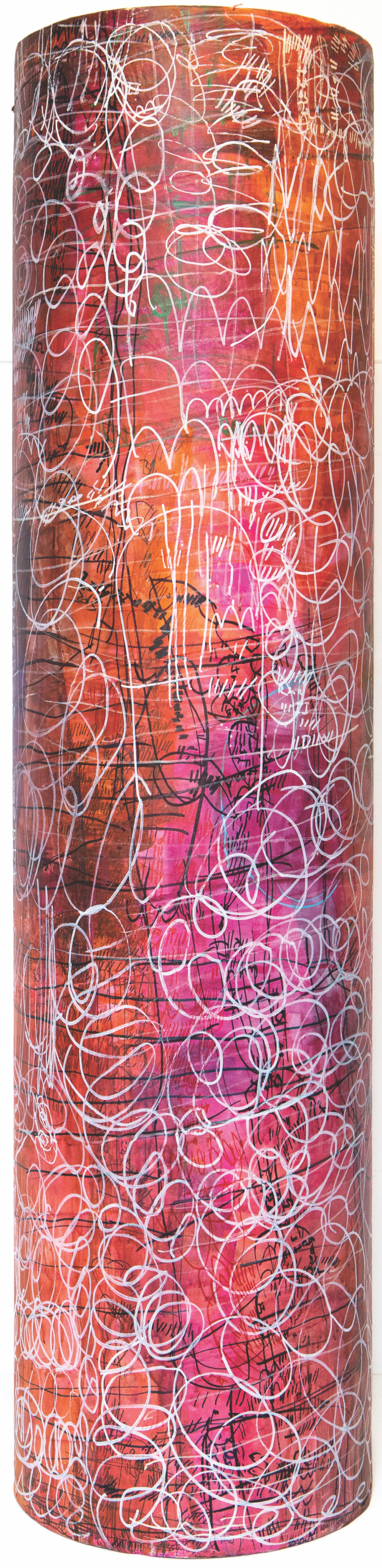

Artists at Creative Growth use a variety of artistic strategies, constantly defying the art market’s expectations for expressive gestures, portraits, and landscapes. Many artists no longer depend on Outsider Art Fairs for their commercial success. Nicole Storm is ambitiously seeking out solo exhibitions and collectors for her work. When she first began making art at Creative Growth, Nicole hid away in cardboard boxes, drawing in the calm of enclosure. Now she moves about the studio space in what di Maria described to me as “nomadic wanderings.” She dances and chats with other artists and sets up her painterly drawing practice at one of the many wide tables. Nicole finds her material by scavenging in the hallways and storage cabinets. Of all the artists I met at Creative Growth, she seemed the most immersed in her process, although I could not understand whether that process had a purpose or not. Her tally marks on cardboard seemed meaningful to her, but she eventually covered them up with paint, and I was left unsure whether she did this as a gesture of erasure or layering. But it was clear that Nicole sees her work as connected to her environment. She was one of the first artists to have a solo show at Creative Growth’s gallery when it reopened after the pandemic in 2021. Later that year, White Columns in New York asked her to create a similar installation in its gallery. Storm filled the white walls with her fluid, glowing paintings. In one corner she placed a brightly painted cardboard box, referencing her beginnings at Creative Growth.

In Our Sanctuary, a piece recently exhibited at the Oakland Museum of California, Nicole arranged abstract paintings in thin washes of blue, orange, and red on brown cardboard, freestanding paper cylinders, and posterboard of varying sizes to cover an alcove from floor to ceiling. To install the piece, Nicole lay down on her back and directed a museum staff member, who hovered above in a mechanical bucket, where to hang her work. She then painted and drew on the white walls between the pieces of cardboard to create a site-specific installation that conveyed her profound sense of comfort with the creative process. The space was a haven of glowing orange and purple tones. She created much more than just art to be displayed by a museum, or work to be paid for. She was making a place to belong.

It would be easy to see the growing prominence of the work of Creative Growth artists like Nicole as evidence that our world now values the art and the lives of people with disabilities. Some artists that Cardinal would have considered outsiders are now on the inside; their work is included in major museum collections and is priced on par with that of nondisabled artists. This is an ambitious and just achievement. But there is a limit to their insider status in a world that does not see most people with disabilities as valuable—that is, as able to contribute productively to the economy. Like many people receiving social security benefits and Medicaid, Creative Growth artists are at risk of losing health care, transportation, and other vital forms of support if they have more than two thousand dollars in assets. This restriction complicates their ability to earn money and support themselves as artists.

“Did you ever think good news could be such bad news?” Diane Storm joked, referring to the irony of the situation. The good news is that internationally renowned museums and galleries want to exhibit Nicole’s work and pay her for it. The bad news is that getting paid compromises her benefits and health care. The rules of Social Security Disability Insurance permit Nicole to earn only eighteen thousand dollars per year before she would be forced to pay back some of her benefits. Nicole depends on Diane to navigate the bureaucratic red tape, as it is notoriously hard to play by the rules of the Social Security Administration. “The system is designed to confuse us,” Diane told me. They report Nicole’s earnings honestly, but it often feels like a shot in the dark. “We don’t know what we’re doing,” she said, “but they [the SSA] don’t know what they’re doing either.” Creative Growth takes a commission from artist sales—the art world standard of 50 percent—that goes to pay for supplies and gallery costs. But even after the commission, Nicole’s income from her art and installations is beginning to reach the limit of what she can earn without the potential loss of her benefits.

The outsider artist model allows the art world to remain comfortably unaware of how our society persistently impoverishes people with disabilities by drastically limiting their income. If creativity is something intrinsic though vaguely defined, then we need not worry if people with disabilities have access to it. The reality that these artists lack social support, adequate health care, employment, and equal pay can remain conveniently outside the scope of art institutions. Creative Growth functions between these two worlds, fulfilling the needs of its artists while also depending on the financial interest of the art world. It provides a path through a bureaucratic and capitalist system that so rarely offers people with disabilities the dignity of work.

In many ways, the routine of artists at Creative Growth takes the shape of a workday. Most artists arrive around nine in the morning, take a lunch break, and leave in the late afternoon. They work side by side at tables, focused on their own projects, but also take time to socialize with others in the open space. Working at Creative Growth mimics the pace of a job, except that it isn’t a job, at least not in the way our society usually conceives of one. Creative Growth gives people with disabilities routine, purpose, dignity—all benefits of the best kinds of jobs. But ultimately, those in the program are not working in response to the expectations of bosses and industry. They are making art, which defies our society’s normative sense of work.

I am told that the families of some of the artists, especially the younger adults, question whether drawing, modeling clay, or painting at Creative Growth is an acceptable way to spend time. They are skeptical of the value of making art, and, like the families of so many nondisabled artists, wonder whether their loved ones would be better off trying to get real jobs. But opportunities for disabled adults to get a real job are appallingly low. Only 19 percent of adults with intellectual disabilities are employed in the United States. Our society defines disability as the inability to do work. This has created the need for places like Creative Growth. In other words, access to creativity is something we owe those who come here, because the world outside has struggled to offer them much else.

When Nicole was growing up, Diane had no expectations that her daughter would eventually find a job, but they were open to exploring opportunities. Nicole tried out a few jobs before she came to Creative Growth. She worked as a maid at a local bed-and-breakfast, but she had no structured support and there was constant pressure to fold and clean sheets and towels more quickly. She then worked at a few chain restaurants and coffee shops. But they were too fast-paced, and sometimes Nicole would get irritated with the customers. Steady work never seemed like a good fit for her. But whether this was because of a cognitive impairment or Nicole’s creative spirit no longer really matters. “She is an artist,” Diane told me.

Our world judges a person’s value by their ability to work. Yet work isn’t necessarily dignified or humane. In The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World, Lewis Hyde distinguishes between work and labor. Work is what we do for money, Hyde tells us, but labor sets its own pace. It is often accompanied by idleness, or a period when one might seem to be struggling to be productive in a capitalist sense. Labor, according to Hyde, is “often urgent but… nevertheless has its own interior rhythm, something more bound up with feeling, more interior, than work.” For Hyde, creativity is aligned with labor more than work. His words in The Gift take on a transcendent tone, exalting the preservation of creative labor in a world that constantly asks us to live for money and what we can buy with it.

In its most idealized form, creativity stands apart from work and outside economies of value and time. It maintains a kind of purity and disinterest. Monetizing or quantifying creativity, we tend to believe, corrupts it, giving it a pragmatic purpose that sullies its connection to truth and the human spirit. In this way, creativity and art are profoundly worthless. But during my visit to Creative Growth, Hyde’s distinction between work and labor seemed too simplistic. To see the artists as laboring would mean to see them as outside systems of work and economic value. It would place them apart from the economy that structures our lives. And as flawed as a capitalist economy is, people with disabilities deserve the option to be fully part of it. Labor, in the way Hyde explains the term, would imply worthlessness, and so it would be a problematic term to use in the context of Creative Growth. To call the labor of these artists worthless is to come dangerously close to calling them worthless, to repeat the historical marginalization of the lives of people with disabilities that the Katzes originally fought against. The acknowledgment of the value of a person’s creativity has social and political importance, and work and labor are intertwined in necessary ways.

It may be true that Creative Growth artists aren’t totally outsiders anymore, but the studio must still navigate between the ableist tendencies of the established art world and the needs of the disabled community. Creativity and individualism are given value here, but that does not mean the art studio is untouched by the pressures of ableism and productivity that are part of our capitalist world.

A few days into my visit, Donald Mitchell, an artist who has worked at Creative Growth since the 1980s, came back after being gone for several months, due to issues with his living situation and problems securing transportation from his home to the studio. “We lost track of him,” di Maria told me, “but it took him about a minute to get started this morning.” He announced Mitchell’s return, and I sensed some relief and lightness in his voice. The other artists and staff members broke out in applause. The moment felt like a homecoming. It was a reminder that Creative Growth is more than an art studio, but a way of keeping track of people who can fall through the cracks. Most of the artists access Medicaid with the help of California’s Department of Developmental Services (DDS). The studio is a service provider through the Regional Center of the East Bay, one of about twenty private, nonprofit corporations under contract with the DDS. Most of the other service providers that are part of the Regional Center of the East Bay are residential homes and care centers. Creative Growth, Creativity Explored, and NIAD—all started by the Katzes—are among a handful of art studios that are also service providers.

When the Katzes began Creative Growth, there was very little social support for people with intellectual disabilities who wanted to live independently. Now there is more. Because they receive financial assistance through the Regional Center, most artists have an Individual Service Plan (ISP), which requires the staff to help artists develop goals for their practice, but the document might also include social or behavioral milestones, like developing strategies to create relationships or follow rules. Portfolio reviews are also part of the ISP, and each report notes which exhibitions the artists has submitted work to, the works of art completed, and the time clocked in the studio. Each staff member at Creative Growth is assigned a caseload of six to eight artists. But the staff, who are also artists themselves, make for awkward bureaucrats. Last spring, they declared their intention to unionize, reflecting the gradual pressure to evolve from the collaborative, community-based relationship between staff and artists that the Katzes established to something more formal. Even here, paperwork and other, more tedious aspects of work have their place alongside creative labor.

All this bureaucracy is at odds with Cardinal’s outsider artist, and Hyde’s conception of labor, both free from social and cultural constraints. Artists come to Creative Growth to create, to learn, to be together. But they are caught between two ways that insiders make sense of outsiders. On the one hand, museums and collectors still tend to understand the creativity of outsider artists as the outcome of expression and mysterious drives. On the other, the artists are subjected to documentation, in which getting what they need from the system depends on how useful and productive their time appears to those at the DDS.

I recognized the reports and goal-setting from my daughter’s own assessment in school and the familiar routine of playing by the system’s rules so she gets what she needs. The Individualized Education Program (IEP), a government document that develops and changes with my daughter as she moves through school, provides an agreement on goals and accommodations that is similar to the ISP submitted for many of the artists at Creative Growth. Every year my husband and I meet with a team of educators to review her educational progress. My daughter’s most recent IEP included a “measurable postsecondary goal.” This is intended to help prepare her for competitive integrated employment, or work among her peers for equal pay. This is a notable difference from the world Nicole and Diane faced decades ago, when not being institutionalized seemed like a remarkable step forward. But people with intellectual disabilities still struggle to find appropriate jobs. My daughter is being asked to think about what she might like to do after high school, and hopefully by the time she is ready she will be able to find fulfilling work.

By fighting for access and the recognition of their own human dignity, disability-rights activists have led the way in demanding innovations that have improved the broader world. Curb cuts began to be implemented nationally after Ed Roberts revealed the need for more accessible urban spaces in Berkeley. Disability accommodations in higher education have forced society to start to question its narrow definitions of learning and the value of achievement. For their part, the Katzes envisioned an alternative definition of work. While navigating between creativity and bureaucracy, Creative Growth shows us a way to work that is not defined by productivity but by dignity and shared responsibility.

The Katzes dreamed that eventually the establishment of art centers for people with disabilities would be unnecessary, and that in the future, “all people will be able to work together toward the highest fulfillment of each individual and of society as a whole.” They imagined the full inclusion of people with disabilities in society, and their access to meaningful work. Fifty years later, we are not there yet. Reaching the Katzes’ goal will require more than just the acquisition of art by people with intellectual disabilities by major museums. It will require changing our society’s ideas about work and creativity. It will demand that we recognize that all humans have a right to access both.

Until we get there, Creative Growth artists continue to change the art world by contributing to it. Nicole Storm is now a successful artist with exhibitions scheduled at international museums for the next several years. Her art seems still to be a product of her nomadic wanderings, of searching for materials in hallways, and with a purpose that is clear only to her. But since Storm’s work has been in greater demand, she has started to approach her art with greater urgency. “She has a tremendous work ethic,” Diane told me. “When she has a deadline, she works.” It’s an approach that defies a more simplistic separation between work and creativity. “I want to get a paycheck,” Nicole said. But there’s more to it than that. And what seemed clear to me when I talked with Nicole and Diane is that they see Nicole’s art as a product of their circumstances, which are deeply informed by their love for each other. On the days when she doesn’t go to Creative Growth, Nicole sets up her studio in their home while Diane gets breakfast. “Nicole’s art gives us a sense of focus and brings us together as a collaborative team.” As a mother, I know this is one of the most gratifying experiences a caregiver can have. “I feel very lucky that she includes me in her life,” Diane said. I thought about my daughter and how lucky I would be—how lucky any of us would be—to have a future like this.

I am unsure if I want my daughter to have what most people would refer to as a “real job,” although I recognize that she will need to financially support herself. I hope she will choose what is best for her. Right now, she wants to be a scientist, a ballerina, and an artist, but there is no way to know if those dreams will pan out. I imagine the drudgery and monotony of the jobs that might be available to her, and my heart starts to race with panic about what her future might hold. I wish for more for her than work. I want her to find creativity and self-direction, but there are so few opportunities for a creative life in the modern world. In the daily work of Creative Growth, there is a different conception of productivity, and a different conception of human worth. It provides artists with a sense of meaning and purpose, which is a remarkable difference from a world where a life can seem to have little value if it is not profitable and productive.

According to modern parenting, I am not supposed to want my daughter to be an artist. And the broader world tells me I should be grateful if my daughter finds a job at all. But maybe employment is only part of what we should want for people with intellectual disabilities. The truth is that I want my daughter to find a supportive community that helps her cultivate her own unique contribution to the world. I want her to be an artist, and I also want her to make money and be part of an economy that respects and values her contributions to it. The problem is that these things seem rarely to coexist. My daughter will be asked to either complete oppressive work or not work at all. Art and work so rarely function together. But I have seen the possibility of an alternative future in which value is determined not by productivity, but by codependence and love.