It’s a blustery Tuesday morning in mid-January, one week into the Ukrainian New Year. The plainclothes team of Oleg, Vanya, and Vova are sitting in their unheated office on Mercanskii Street. They are chain-smoking, fogging up the bare, icy room with blue clouds, using their counterfeit Marlboros to plot out the day’s appointments.

They are known out on the street as the Third Reich, and they like that name.

Out the dim window, Dneprodzerzhinsk, population 350,000, spreads itself across both banks of the Dnieper River like a big mistake nobody has owned up to yet. Known for its tough cops, the city was named after Felix Dzerzhinksky, the feared director of the Soviet secret police, what became the KGB. Life expectancy here—after seventy years of Communism and fifteen more of the nameless and confused philosophy that came after it—pirate capitalism?—is said to be 56.5 years for males.

Whatever it is, it’s falling, and falling fast.

Today the team’s beat will cover the residential east side, the left bank of the river, a shabby neighborhood of 100,000. The men take their time, they know what they are doing. Their “customers” are just getting home now from a long night, some of them. One cop holds up his cigarette and examines it speculatively. The other rubs his military-style cropped scalp. The third smiles at nothing, a Buddha of the North, and silently stubs out his smoke on a cracked soap dish.

“Let’s go,” he says. It’s Oleg, the good-looking one.

The one the hard boys on the street call chort—the devil.

Should they visit the heroin dealer first? Or the B and E ring on the Mir square? At some point they will want to look in on their two teenage prostitutes, Zenia and Yulia—both sisters’ babies are sick and malnourished. They will have to take the kids away if the mommies are doing heavy drugs. This is their technical specialty: underage criminals.

The young men slowly get to their feet and put on their snappy black leather coats. Maybe they will begin with the TV-booster ring; the dope dealer will be sleeping until noon. Logistics are everything on this job; the paramount concern is to save gas. Plainclothes cops in Dneprodzerzhinsk must pay for their cars, their gas, ballpoint pens, and office paper—even their own handguns.

“All you get is a chair when you join up,” says Vanya. “A wooden chair, that’s it. The rest you must supply yourself.”

Today they are using Vanya’s car. A five-year-old blue Lada sedan, no markings. They don’t use warrants and they make no big show of brass badges, either. It’s all very informal, this Ukrainian police business. They simply show up in force, burst through the door, and get to work, looking for drugs, stolen property. Stealing elevator shaft equipment is the safest and most lucrative game, so many apartment elevators don’t work. Guys can pocket $125 for an hour’s work, spend it on home-cooked meth, and stay up for seventy-two hours, gambling, whatever…

On this shift the squad will be visiting four sets of rough customers, but nobody the three of them can’t handle with fists and swinging doors.

“First thing we do is break their noses. We never take our guns to the job,” explains Vanya, thirty-two, “because if we use them they make us pay for the bullets.”

Outside, the stuttering January morning breaks over the rotting pastiche of twelve-story concrete apartment buildings and coal-processing plants. There’s some trouble getting the Lada started. Still, the men are happy to point out the positive aspects of their hometown, boasting without apology.

“Here’s a good place for black tea! The real stuff!”

“Look at that redhead waiting for the bus! What a body!”

They say the local girls like the cops, even the bad girls like them. More smokes come out. But now it’s the contemplative smoking, not strategy-smoking they’re doing

The Lada heads straight north. The available light is dim, wholly indistinct. A treacherous-looking, queasy industrial light. Vova begins to hum, it sounds like a Broadway show tune.

The theme from Titanic? Cats?

There are worse jobs out there, and these guys know it.

Dneprodzerzhinsk is an alarmingly postindustrial city, located a few hundred kilometers from Ukraine’s eastern border with Russia. Famous for its striking coal miners, and, more recently, for its threats of separatism from western Ukraine, the eastern half of the country thinks of itself as rock-hard, cold reality.

“What would the rest of the country do without our coal?” Vanya rhetorically asks. “Freeze their asses off—that’s what! Waiting for the Asian hordes to invade.”

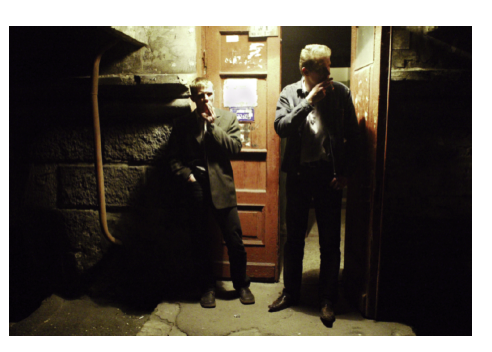

Here we go. The first stop of the morning.

A peeling ferro-concrete apartment tower, with a dark green entranceway.

It’s dark because the lobby lights have burnt out.

Bodies are moving forward quickly in the dark, moving by instinct.

Just follow us, the boys caution, don’t say anything.

The elevator takes forever to drop, it doesn’t put them off at all.

Third floor.

They knock at a steel door plastered with soccer hero stickers.

And wait.

The door opens a crack and they don’t wait to be asked.

They push forward like they own the joint.

“Viktor! We’ve come to visit our old friend!”

Now it begins.

Now the three men do what cops the world over must do.

Take the streets or get buried in them.

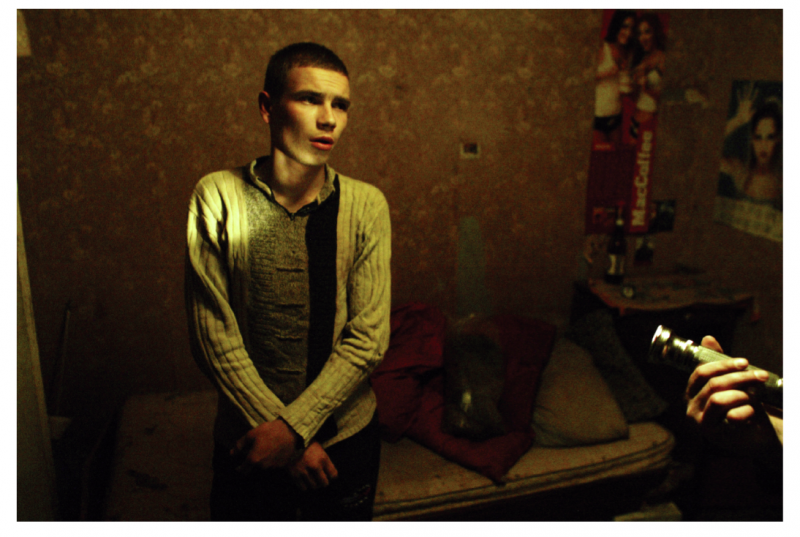

“So, old man,” they say to the quaking, white-thatched occupant, a lean fellow about fifty. From his well-kept hands and scattered books, he might have been a high-school teacher, a lifetime ago. “You keeping out of trouble?”

“I—I—I,” Viktor stumbles, wipes his hands on his pants, trying to get the words out by sheer force of will.

The cops plainly don’t like Viktor.

They don’t like his irksome manner, that faint smell of former State-educated social superiority, his pleated trousers and cheap running shoes. They don’t like the way Viktor speaks, either—he stutters badly. But they’ve got him, so they’re in no rush now.

“I—I…”

He can’t get the placating words out.

Not even a tak, a dutiful yes, or proshu pan, please good sir.

“I—I.”

Yes, he’s lost, and he knows he’s lost.

His bony face is full of wild grief like a December deer’s, a trapped creature who knows the pack is moving into final position around it.

His whole body is keening with anticipation.

The strike could come from anywhere.

“We heard you been dealing dope, Viktor dearest! Think you can make it through prison at your age?”

“B—b—b!” Viktor clenches his fists, squeezes his eyes shut in a vain attempt to freeze out the probing looks of Oleg, who is watching him like Satan watching his younger brother Jesus on the cross, enjoying every delicious drop like fresh cider.

A moment of silence.

Nobody’s breathing, everyone’s waiting.

Taking account of the situation.

“Selling dope! To kids! You should be ashamed, Viktor! How low can you go! You were an engineer, for God’s sake!”

The three men form an inflexible triangle around Viktor, and he can’t help himself. His eyes dart involuntarily to the clothes closet and Oleg has him.

Just like that.

He nods at Vanya and Vanya finds the shoe box behind the books, and pulls out the sealed baggie of Crimean marijuana from a woman’s high-heeled shoe. It all happens in a minute, and now he’s waving it under Viktor’s nose.

“What’s this, old man?”

“I—I—I,” Viktor blanches. This is all happening too fast, his black sugarless tea is getting cold on the vinyl-wrapped table, and he will never finish it now.

Wham!

Viktor is suddenly flat on the floor. Oleg’s hard black shoe is planted on the back of his neck.

The team squats, and one waves the dope-baggie under his nose again.

“Where did you get this, old man? Who’s supplying you?”

“Viktor… Viktor.”

One of them is doing something to the prisoner’s arms.

He’s searching for tracks and wrenching them from their sockets at the same time.

To his shame and discredit, Viktor begins to cry.

He knows this is a big mistake, that the cops will take his tears as a provocation, but he can’t help himself. All his life he has stuttered, now he must take what they are going to dish out. It’s either them, now, or that hard man who sold him the dope on consignment, later. Either way he will get beaten, and to avoid jail he must give them something for all their trouble besides a forty-dollar bag of second-rate dope.

Now the boys light fresh cigarettes, and ignore the supine man at their feet.

Are they letting him think? Think about how he’s going to deliver their morning’s reward? Or are they merely surveying the unfolding of yet another new day, like mountain climbers who have succeeded in mounting a preliminary peak before lunch?

The “Third Reich” is well-known on this beat. They are called the Third Reich for a reason. One of them picks Viktor up from the floor and leads him into the bedroom.

He shuts the door behind him.

It’s 10:55 a.m. The sun is coming out, casting the city in the bright relief of midwinter and providing the illusion that spring could come any day now.

The other two boys talk about their job, for there is nothing to do but wait here in this stale kitchen, not until Viktor gives up the names in the other room. They say their job is unrelenting but rewarding. It hasn’t changed much from the days of Dostoyevsky and the Cheka. Not in its essentials.

Police work in a postpolice state? It appears to be a curious blend of behaviorist psychology and Byzantine morality. It seems

a profoundly romantic enterprise, too, because here in Ukraine—unlike the West—everyone agrees on the basic rules.

They just don’t necessarily follow them.

What did Dostoyevsky say in Crime and Punishment?

“Ha-ha! You notice everything at once, don’t you?” the murderer Raskolinkov asked, somewhat rhetorically. “They say of all our writers, Gogol possessed this gift to the highest degree.”

Gogol was, of course, Ukrainian. And these street cops, thieves, and drug dealers can all quote him at length, Gogol and Dostoyevsky and a dozen other Slavic writers. It may be the cops’ turn next, and they all know it. Many cops, perhaps 15 percent of Ukraine’s total police force, will end up in jail for extortion, drug dealing, and possession of stolen property. There you go: Gogol and Dostoyevsky were right. Life is a quick ride through a terrible landscape, relieved only by moments of drunken sociability and spiritual insight.

A mass-produced tapestry hangs in many Ukrainian homes. It shows a careening winter sleigh, loaded with terrified passengers, pursued by steppe wolves. The flight is from the country’s dangerous history and the wolves are its terrible past: the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, the Forced Famine of 1933, the Patriotic War of 1939–45, the Chernobyl Disaster of 1986, the Economic Collapse of the early 1990s.

Now Ukraine’s abject underclass calls its latest wolf—democratsii.

From The Human Is an Atom That Won’t Be Split: Ukraine from Below, a collaborative project, which was awarded the 2006 Dorothea Lange–Paul Taylor Prize from the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University.