A few years ago, I started listening to birds. Of course, I’ve heard birds all my life, and since I’ve always lived in the Bay Area, I’ve probably heard the same handful of species again and again. But there’s a difference between hearing and listening. The longer I listen, the more there is to hear: not just the sounds of different species, but of individual birds making different sounds at different times and in different situations. If places and times could speak, so much of their audible language would be that of birds.

[Editor’s note: click on the headers to hear the bird calls.]

California Towhee

The California towhee, a beige midsize sedan of a bird, does not have what we would ordinarily call a song. Instead, it emits a loud, periodic beeping that sounds like a smoke detector running low on batteries—a noise my dad refers to as a “chirp bomb.” You’ll hear it from below rather than above, since towhees like to forage through leaf litter, quickly jumping forward and back in search of bugs. My neighborhood in Oakland is full of this mix of dry rustling and beeping.

California towhees aren’t as simple as they seem. While they look to be colored a dull brown all over, closer inspection reveals a bit of orange streaking just below the beak and under the tail, prompting me to nickname them “secret orange-butts.” Their sound repertoire, too, is more complex than chirp bombs: very occasionally, I will hear one or more of them let out an agitated sound, descending in pitch, that I can compare only to someone using a squeaky marker on a whiteboard to draw tighter and tighter squiggles. This signals towhee drama, as far as I can tell, since it coincides with the birds chasing one another through the shrubbery.

Most of the time, though, the beeps are all you hear. Generic as this “song” may seem, it is actually quite geographically specific: the range of California towhees is restricted almost entirely to California and Baja California. And because they are present all year round, the steadiness of their chirps has begun to remind me less of a smoke detector and more of a clock marking local time.

Mockingbird

Have you ever heard a bird singing loud, complicated songs long into a summer night? If so, it was probably a northern mockingbird. The internet is littered with complaints about this phenomenon: “What can I do about a bird that sings all night long outside my window?” “Rude mockingbird sings loudly all night.” “A mockingbird has been singing loudly for 16 hours a day above my house for 2 months, how do I make him go away?” “Jerk bird singing in the dead of night.” And so on.

A male mockingbird will sing endlessly until he finds a mate, so the solution is simple: find him a girlfriend. An understanding of the bird’s motivations can, at least, endear someone to his ill-timed, boasting song. Mockingbirds sometimes keep me up when I visit my parents in the summer, but I don’t mind. I lie awake and try to pick out the birds the mockingbirds are mimicking—they can imitate crows, goldfinches, titmice, and others, jumbling all these songs together into one improvised jazz solo. Not that they limit themselves to copying other birds. They’ve also been known to belt out cat meows and car alarms, which has prompted another internet call for help: “How to train a mockingbird to sing something less annoying.”

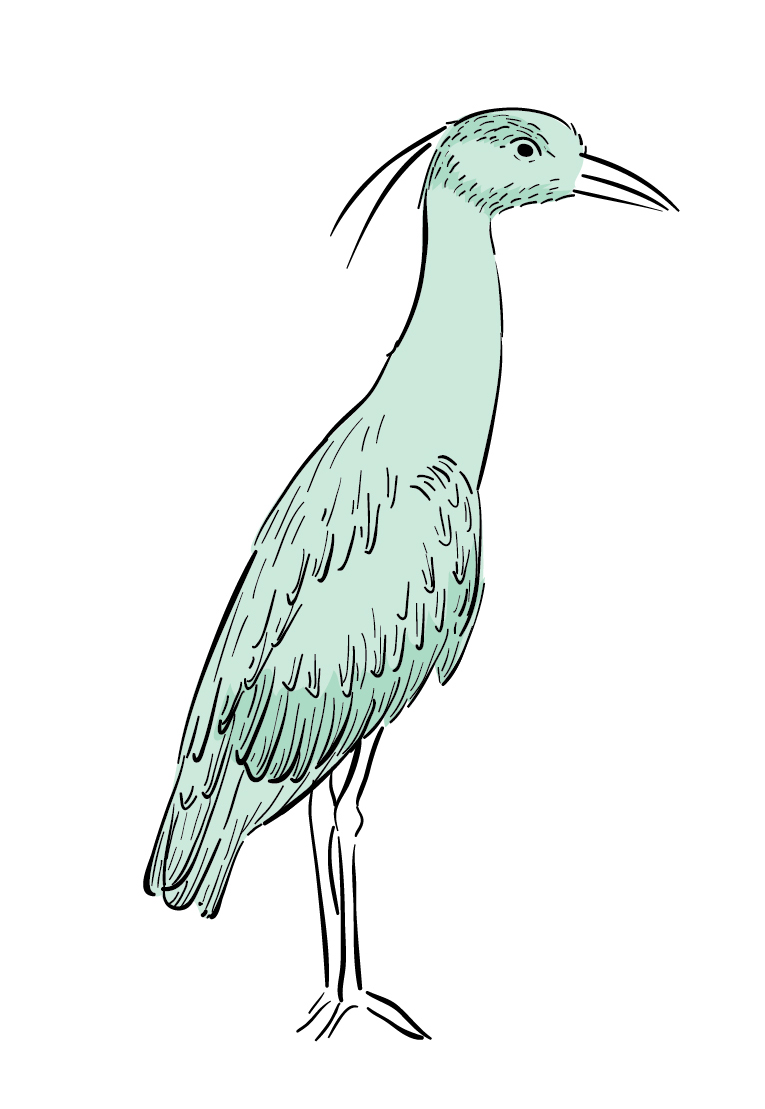

Night Heron

In many parts of the country, dusk brings with it a strange sound. The word for the sound is often spelled “quok,” like a bizarro cousin of a duck’s quack, and at times sounds so human that I’ve turned around, expecting to see a person. Then I think twice and look skyward, where I see one or two night herons on their way to a nearby lake. Night herons are so called because they typically hunt at night, when there is less competition from other heron species. But in many languages besides English, their name is determined more by their sound than their schedule: they are kwak in Dutch and West Frisian, waqwa in Quechua, vạc in Vietnamese, kvakoš nočn in Czech, and quark in the Falkland Islands. I get excited every time I hear the quok. Although I’ve read that night herons sometimes make other sounds (like rattling their bill upon greeting a mate), they are generally still and silent birds, so when they speak, I listen carefully. And as Arthur Cleveland Bent notes in his 1927 Life Histories of North American Marsh Birds, night herons most reliably make their “loud, choking squawk” on evening trips to marshy feeding grounds. The song begins to create a Pavlovian response in me at a certain hour. A night heron quoks, I look up, and if I’m lucky, I spot it in the distance, having a brief word before a quiet night of fishing.

Acorn Woodpecker

The acorn woodpecker is a bird of silliness, first of all because it sounds as if it’s laughing. David Allen Sibley, in Sibley Birds West: A Field Guide to Birds of Western North America, describes its call as “raucous laughter” (which he spells “RACK-up, RACK-up!”). The birds frequently make this monkey-like sound while chasing one another and redistributing themselves through oak trees. If you can get close enough, you’ll see that acorn woodpeckers look silly too: they have tiny red hats, wide-open eyes, and what Sibley calls a “clownish” pattern. It’s impossible for me to keep a straight face around them. Acorn woodpeckers are so ubiquitous in the foothills of western California that it’s as though the oak trees themselves were laughing.

For a long time, I guessed purely from their sound that acorn woodpeckers were social and gregarious, and I recently confirmed that they do indeed have complex social structures. They live in communal groups with up to seven breeding males, three breeding females, and any number of nonbreeding “helpers.” It would seem that they have lots to talk about and many mates to talk with. I like listening to their chatter, because in addition to forcing me to lighten up, the sounds are a decentering reminder of the existence of a separate, smaller society, complete with its own drama, all the way over there, among the distant oak trees.

Lesser Goldfinch

The calls of the lesser goldfinch capture my attention more easily than those of almost any other bird, I think because they sound so much like human language. The goldfinches where I live will typically alternate between a hoarse “Hmmm?” and a cheery two-note “Hello!” It’s a passerby’s hello, the kind you’d say if you were walking down the sidewalk and saw a neighbor pulling weeds in the front yard.

If no one’s around, I say hello back to the goldfinches in the same tone. “Hello!” they’ll say from a Japanese maple tree when I leave my apartment, stopping me in my tracks. I turn around and shade my eyes, looking for their miniature forms hopping around in the branches. “Hello!” I say when I find them.

During breeding season, some of the goldfinches have much more to say than “Hello.” Males will sing long, virtuosic songs incorporating wheezes, trills, and pieces of other birds’ songs. These solos are so elaborate that it took me some time to realize they were coming from the same tiny, dusty-yellow birds as did the humble “Hello.” My response to these ten-second masterpieces is not so well practiced, though maybe a scat singer could come up with something to say. I just stand there, silent and stupefied.