Even at the height of his success, John Cheever never quite lost the fear that he’d “end up cold, alone, dishonored, forgotten by [his] children, an old man approaching death without a companion.” This, he sensed, was the fate of his “accursed” family—or at least of its men, who for three generations (at least) had seemed “bound to a drunken and tragic destiny.” His grandfather Aaron had been found dead of “alcohol & opium—del[irium] tremens” (according to the death certificate), while his father Frederick had been banished to an old family farmhouse on the South Shore of Boston, where he spent his days tippling and reading Shakespeare to his cat. As for Cheever’s older brother Fred, an advertising executive, he eventually rebelled against his own Babbittry by becoming an exhaustively offensive drunk, and later a sixty-something hippie riding a Harley around Plymouth.

Aside from the Ibsenesque genetic factor, Cheever drank to ease a terrible dread that his family and friends would discover his bisexuality—a secret that sometimes filled him with an almost suicidal self-loathing. By the early seventies, he seemed permanently impaired by alcohol. His face and extremities were swollen, his speech was slurred, and almost any kind of physical exertion made him dizzy to the point of fainting. Most ominous, perhaps, were the spells of “otherness” he began to experience: “With a hangover and a light fever I distinctly get the impression that I am in two places at once,” he wrote in 1972. “I am aware of my surroundings here—rain and the beech trees and [also] I smell the coal gas and see the furniture in [my childhood] house in Quincy. Have I gone mad?” These frightening lapses continued, until Cheever was finally persuaded to attend an Alco-holics Anonymous meeting at a local church. He found it “dreary”: “The long speech I have prepared seems out of order and I simply say that I am sometimes presented with situations for which I am so poorly prepared that I have to drink…. I am introduced to the chairman, who responds by saying that we do not use last names.” For the next three years, whenever the subject of AA came up, he’d explain that he’d gone to a meeting where someone had blurted out, “Hey! There’s John Cheever!”—though (as we see) he’d found it even more distasteful that he wasn’t, in fact, allowed to utter that celebrated name. In any case he decided AA wasn’t for him, and besides: “I think detoxification would kill me dead.”

With nothing but time on his hands, Cheever was tempted to accept an invitation from Frederick Exley to give a reading that autumn at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop—though he was wary about traveling under the circumstances. “I breakfast on scotch and Librium,” he warned his host, “am having an unsavory love affair, and suffer so from Agraphobia [sic] that it takes me a pint of liquor to get on the train.” Perhaps the deciding factor was sheer curiosity: After seven years of lively, candid correspondence, he and -Exley had met in the flesh only once, and then briefly, when the latter received the Rosenthal Award at the 1969 American Academy of Arts and Letters ceremony—this a direct result of Cheever’s efforts. As chairman of the Committee on Grants for Literature that year, Cheever had proposed A Fan’s Notes for the Rosenthal (given to “that literary work… which though it may not be a commercial success, is a considerable literary achievement”) by way of killing two birds with one stone: (1) promoting the cause of a worthy novel written by a friend (of sorts), while (2) scuttling his despised rival Donald Barthelme, whose collection Unspeakable Practices, Unnatural Acts had hitherto been considered the favorite. “[A]fter his last story in the New Yorker I cannot take [Barth-elme] seriously,” Cheever wrote his fellow committee members. “This leaves me with Exley.” The poet Phyllis McGinley fired back that to eliminate Barthelme “on the strength of one failed story” seemed “captious,” and besides she “didn’t find Exley up to his reviews.” Lest he appear to rule by fiat, Cheever diplomatically circulated a ballot including the names Exley, Malcolm Braly, and Richard Brautigan (but not Barthelme).

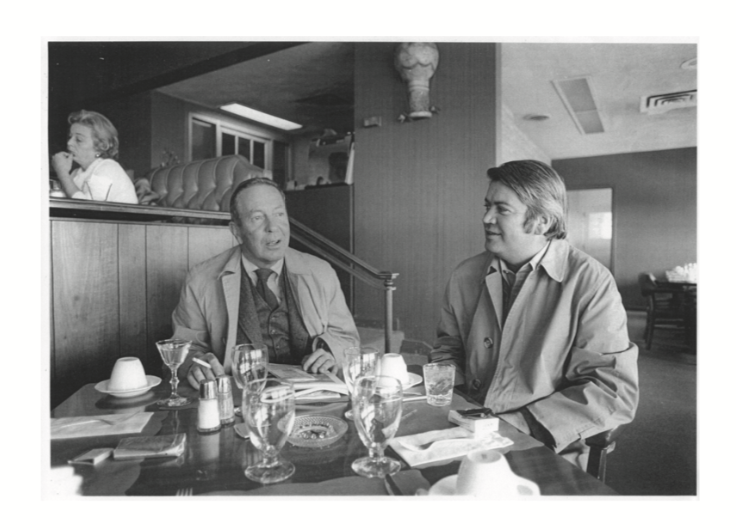

Even Exley—whose name is virtually synonymous with alcoholism—was impressed by Cheever’s drinking. As he recalled, “No sooner were we on the highway [from the Cedar Rapids airport] that John reached into his raincoat pocket, pulled out a beige plastic pint flask containing gin, invited us to have a belt, we declined, John took a healthy swig and returned the flask to his pocket.” Exley showed his guest to a room at the Iowa House, then inquired whether it would be all right if a nice young man came to interview him for the campus newspaper; Cheever was happy to oblige. “I like Exley,” he said, when asked what writers he admired. Any others? “I like Exley.” Nobody else? “I like Exley.” So it went. Since Cheever had arrived a few days early, he and -Exley filled the interval with a pleasant routine: Each morning they’d meet at the downstairs cafeteria for “shaky cups of coffee,” then embark on an all-day round of campus saloons. “Hi Fred!… Hi Ex!” shop clerks yelled from their doors as the two -writers shambled along. When Cheever expressed amazement at his friend’s celebrity after only ten weeks in town, Exley “beamed modestly” rather than explain that the clerks were hoping to be introduced to Cheever, whose arrival had been widely trumpeted in the local press.

Perhaps Exley should have men-tioned as much, since -Cheever’s self-esteem was at a very low ebb, which meant a certain amount of compensatory haughtiness was almost inevitable. The writer Vance Bourjaily’s wife, Tina, had gone to the trouble of birthing a lamb, feeding it only the best grass, assisting in its slaughter, and roasting it to perfection in a pastry crust for their distinguished guest—in return for which she received a bit of muttering condescension. As she remembered with lingering pique, “[Cheever] sat on his pompous ass at the dinner table saying ‘Imagine eating d’agneau en croˆute in Iowa!’ He probably never tasted a finer one unless he had eaten at the four star restaurant out in the wilderness of Southern France where they gave me the recipe.” Likewise, when Exley tried to talk him out of reading a story as lengthy as “The Death of Justina”—with worsening laryngitis yet—”John drew himself up to his full five-feet-five and in his insufferable tones proclaimed something like, ‘Ah’ve read “The Death of Justina” in Moscow, Leningrad, Stockholm [etc.]… and if it’s good enough for those places it’s damn well good enough for Iowa City.’” Sure enough, his voice began to fail around the middle of his reading at the Clapp Recital Hall (“Hoarseness is not, thank God, a symptom of Clapp,” he remarked), and afterward he complained to -Exley about the size of the audience: “I thought you said Styron packed the place!” In the company of students, however (especially Ex-ley’s twenty-one-year-old girlfriend), Cheever was at his funny, self-effacing best, and in hindsight he viewed the visit as an almost unqualified triumph. “That was great fun although I do worry about all the tabs you picked up,” he wrote Exley. “We seem to have something basically in common, something more lambent, I hope, than hootch and cunt.”

Indeed, Cheever had found Iowa City so “serene” that he considered teaching there the following year, when Bourjaily was planning to take a sabbatical. Jack Leggett, the Workshop director, was all for it, and everything seemed in order except a few “imponderables,” as Cheever put it: “I don’t know what to do about this house, [and] my marriage is in the annual dumps…” His wife Mary, to be sure, was not keen on the idea of going to Iowa with her drunken husband, who moreover was liable to kill himself if allowed to go alone. The discussion escalated into mutual threats of divorce, until finally it was decided that everyone would go their separate ways in the fall of 1973: Mary would remain in Ossining, while Cheever went to Iowa and his son Federico to boarding school (And-over). “Who cares?” Cheever said, when friends wondered how he’d manage alone in the sticks. “Feed me to the pigs.”

*

Apart from the usual domestic crises, nothing much happened to Cheever between his Iowa trip in November 1972 and the publication, in May, of his sixth story collection, The World of Apples, which coincided almost exactly with a long-overdue brush with death. One episode in the interim seems exemplary. That spring he was invited to give a reading in Provincetown, where he’d spent many happy days in his youth. “It’s easier to get to Egypt,” he replied by postcard to Molly Cook, chairman of the Fine Arts Work Center, who replied that she and Roger Skillings would be happy to retrieve him in Ossining. What ensued, as Skillings wrote the poet Stanley Kunitz, was “a kind of nightmare.” Following directions provided by Cheever, they arrived at the house of a “large florid whitehaired man” who appeared to be in the process of repairing TV sets. “Who do you think I am?” he finally asked, having served them jelly jars of vodka. They told him. “Oh no,” he said, “I’m Johnny Curtains, Cheever lives up the road.” They found Cheever in high dudgeon and drunk, as he’d gulped a great deal of gin while waiting for them to arrive. He soon calmed down, however, and insisted on reading them a story from his advance copy of The World of Apples; with Mary and Federico in bemused attendance, Skillings lit a joint and settled back to listen. “I can tell it better than I can read it,” Cheever said after an “interminable” attempt to negotiate the text, and so he did while his wife devised a map to the Watergate Motel in Croton, where Cook and Skillings were to spend that Friday night.

Cheever had been drunk but dignified, lordly even, in his own home, but a very different Cheever began to emerge on the road to Provincetown. His respectable friend Art Spear went along as a minder of sorts, though both pulled freely from flasks (gin in -Cheever’s, sherry in Spear’s) and were plastered by the time they stopped for lunch at a diner in South Dartmouth, where Cheever indulged in a lot of Fitzgeraldian hazing of the waiter. That night, before the reading, Cook and Skillings had planned to take their guest to dinner at Ciro and Sal’s Restaurant, but when the time came he was nowhere to be found. After a frantic search, Skillings spotted him wandering down Commercial Street: “[Cheever] gave me an immense long hug,” Skillings noted, “which gave me the willies because I thought he’d gone to sleep.” An elderly Hazel Hawthorne, one of the great benefactors of -Cheever’s youth, exuberantly greeted him at the restaurant—“Joey!”—and Cheever re-sponded with a kind of bewildered bonhomie (“He barely knew her,” said Cook). The poet Mary Oliver was supposed to introduce Cheever at the Work -Center, which was mobbed for the occasion, but before she could work her way up to the podium, Cheever had already begun: “[H]e read ‘The Death of Justina’ very well, considering,” Skillings related to Kunitz, “but his heart wasn’t in it, and then everybody went over to the barn for a party where he kept sticking his tongue in my mouth and asking me how could I resist him.” Cheever explained that he’d “discovered homo-sexuality at Sing Sing” (where he taught a writing class to convicts) and wanted to give it a try, but Skillings resisted being pinned to the bed and finally persuaded him to desist. Art Spear was presumably elsewhere.

It got worse. Spear caught a plane the next day, but Cheever gave no sign of leaving: Nice people were providing drinks and food, he liked the scenery, and anyway, why go home? “We were little drudges,” Cook recalled, “and he expected it. He would thank us politely, but not enthusiastically.” On Sunday, because of the blue laws, Skillings had gone round to friends’ houses borrowing Scotch for Cheever, and very early on Monday Cheever said that he needed a morning drink “for the first time in [his] life.” Guiding him to a liquor store, Skillings observed the visible effort on Cheever’s part not to “bolt behind the store and take a belt.” The bottle was empty by noon, and meanwhile Cheever never stopped talking: “He talks mechanically and repeats himself,” said Skillings, “reminiscences without point or perspective…” Expecting dinner, Cheever reported once again that night to Molly Cook and Mary Oliver (both “grey with fat-igue”), after which he resumed making passes at Skillings. “Why do you find me so repulsive?” he demanded. “I won’t hurt you! I don’t even know what the ritual is!” This went on until midnight, when Cook finally coaxed him back to his room and tucked him into bed. “I’ve lost all my friends,” he said, gazing into her eyes. “I’m lonely.”

They got him a ride back to Ossining the next day. “In Provincetown I see the beach, the dunes, the ocean,” he wrote in his journal. “How beautiful it is. I see an old friend [Hawthorne], smoke four joints and have a number of unsuitable erotic spasms. Why should people not respond to my caresses. I’ll never know.”

*

For several months now, along with the usual dizziness and chest pains, Cheever had found it harder and harder to breathe; it was especially bad in the morning, though he’d conveniently discovered that whisky alleviated the problem somewhat. On the morning of May 12, however, he seemed to be suffocating: Coughing uncontrollably, he lay abed quaffing Scotch and smoking cigarettes in hope of some relief, until his family persuaded him to go to the Phelps Memorial Hospital emergency room. As his doctor, Ray Mutter, remembered, “All the cardiologists and internists and everybody were swarming all over him to try to get him out of [heart] failure.” Cheever was found to be suffering from “dilated cardiomyopathy,” an often alcohol-related condition in which the left ventricle fails to eject blood at a proper rate, drowning the lungs and causing the heart to enlarge. Had he waited a little longer to go to the hospital—another drink, another cigarette—he would have almost certainly died.

For three days he lay calmly recovering in the Intensive Care Unit, and then (“like clockwork,” said Mutter) he lapsed into delirium tremens, which had killed his grandfather Aaron. Because -Cheever’s heart was too weak to withstand heavy doses of tranquilizers, he was in for a long bout—-almost five days—during which his foremost hallucination was that he was in a Soviet prison somewhere in Moscow. He thought the intercom speaker above his bed was a Bible they wouldn’t let him read, that the rumble of food carts were prisoners being trucked from one place to another. In a panic, he yanked tubes out of his arms and lashed out, physically and otherwise, at anyone who came near him. His daughter Susan brought him a copy of the New York Times Book Review with a rave review of The World of Apples on the cover, which Cheever thought was a confession he was supposed to sign; he cursed her and threw it on the floor. Meanwhile Federico patiently explained, over and over, that they weren’t in a Moscow prison (“if you’ve ever been to Phelps Memorial Hospital,” he later remarked, “you’d know that’s not the most implausible hallucination you could come up with”), and when his -father demanded proof, he retrieved a sign written in English: “Oxygen: No Smoking.”

However in extremis, Cheever did not forget his own importance and was very high-handed toward the hospital staff (or Soviet jailers, as it were). Susan worried that he’d be treated roughly if left unattended, and insisted that at least one -family member stay by his bed whenever possible. Even his estranged older son Ben was pressed into service: At one point he noticed his father groping about the sheets for a cigarette; then the latter espied what he thought were the lights of a tavern (actually a nurses’ station), and asked his son to trot over and get him a pack of Marlboros and a martini. As Ben remembered in The Letters of John Cheever, his father’s voice became “haughty and crisp” when Ben tried to explain where they were:

“Are you completely without imagination and initiative?” he asked. “If that is not a bar, then why don’t you go and find one? And when you’ve found one, if you’re capable of finding a bar in a state that is crammed with them, then why don’t you buy that pack of cigarettes for me and a double martini?”

“I don’t think I should, Daddy.”

“Well, then, I’ll just get up and do it myself,” he said….

Then he started to get up. This excited the heart monitor, and I was afraid of what the oxygen tubes would do to his nose, so I grabbed the rail of the bed and made a barrier of myself. First he struggled, then he lay back down. Then he hit me in the chest with his forearm. It didn’t hurt, but it did surprise me. He was furious. “You’ve always been a disappointment as a son,” he said.

Finally Cheever was moved to a barred bed and placed in a webbed straitjacket. With almost laudable bravado, he managed to fish a -razor out of his bedside table and cut himself free, then he laboriously squirmed his way out through a hole at the foot of his bed and collapsed onto the floor. “This brought the cops,” he wrote, “and I was put into a second straitjacket—leather with brass bindings and four padlocks.” When the cardiologist visited that night, Cheever roared, “I’ve been shackled!”

After some three rocky weeks in the ICU, Cheever’s heart began to improve. Applauded for his “spectacular” recovery, he celebrated by wheeling himself into the hall at three in the morning and having a cigarette with his son-in-law, Rob Cowley. Around this time Jack Leggett called him at the hospital and told him to focus on getting well and forget about coming to Iowa. “Don’t be silly,” said Cheever, “of course I’m coming!” In fact he was terrified he’d begin drinking again and end up killing himself, and on his sixty-first birthday he went to see a Phelps psychiatrist named Frank Jewett, whom Cheever dubbed “The Boots” because of the man’s preferred form of footwear. His main incitement to drinking, Cheever admitted, was homosexual anxiety, and he went into some detail about his recent encounters with young men. -Jewett—intrigued by the whole “Death in Venice plot,” as he put it, and perhaps a little doubtful as to whether the puckish Cheever was entirely serious—couldn’t resist discussing the matter with his old med-school pal, Ray Mutter, who was convinced that Cheever was toying with the man. Laughing heartily, he related the whole “homo-sexual” business to Susan, who was both amused and exasperated: How was her father ever going to get better if he didn’t quit clowning and level with these people? “Come on, Daddy,” she said. “Why did you go and tell ‘The Boots’ that you were homosexual?” After a pause, her -father laughed: “I guess I just don’t like psychiatrists.”

Home again after almost a month in the hospital, -Cheever’s happiness at being alive was “indescribable”: “There is a sinister shrink in the wings who says that my euphoria is regressive,” he wrote a friend, “that I am high because I’m forbidden to do what I don’t like to do (emptying the garbage) and that if I don’t take his advice I’ll end up in the stews. I’ve told him to kiss off.” A month of sobriety had wrought a dramatic change: His bloated body seemed to deflate, his blue eyes stood out in his head again, and he treated his family with a sort of wan, remorseful courtesy. He was still a very sick man: His left ventricle remained “unruly,” and his heart did a “clog dance” whenever he tried climbing stairs. Still, in the absence of drinking, he longed to be more productive. Sitting in his wingchair or out on the porch, he sipped iced tea and wrote “on air” bits of Falconer he’d been kicking around for over a year. His editor at Knopf, Robert Gottlieb, knew about his precarious health and what had led up to it, and seemed hesitant to give Cheever another lucrative advance. Nor could Cheever, in good conscience, complain much, as he’d yet to write a single finished word of the novel in question: “A nightmare is that I will die suddenly and some editor—Bob [Gottlieb] perhaps—will find no trace of the book,” he wrote that June. “I ought to leave something that looks like a book. So my long vacation continues.” A few weeks later, Gottlieb came around with a hundred thousand dollars, and sometime in August Cheever finally managed to write a few “inarticulate and clumsy” pages of Falconer.

One problem was rust, another was that he’d begun drinking again. Doing so, he’d followed to the -letter the classic pattern of the alcoholic who gets sober in response to some crisis, then thinks he’s capable of drinking moderately and almost immediately reverts to his previous condition or worse. In Cheever’s case it would get much, much worse, though it began with a trifle: “I drink perhaps a tablespoon of whisky,” he noted in mid-July. “The effects are splendid, beyond anxiety, but I suppose I should confess this.” A page later, he wrote: “Alone, I drink a whisky after dinner. It tastes very good. It seems to do me no harm but I must be very careful about this.” Cheever would have found a reason to drink in any case, but since it was summer the most satisfying reason was readily at hand: His wife was -going away to Treetops (her family estate in New Hampshire), and if that weren’t callous enough, she was taking the whole family with her—all but Cheever, who felt very sorry for himself even though the decision to stay behind was, as ever, his. “I might state the facts,” he wrote, explaining to himself why he wanted to drink again, “that I am a very lonely man of sixty-one, malnourished, living alone with a cat, suffering from a heart condition and trying to write off a debt of one hundred thousand dollars before I die.” Still, he made a miniature stand of sorts: Home alone that first day, he poured his gin down the sink and tried to get some work done; then he lunched with friends and went for a swim. A drab day. His work went badly or not at all, and he found himself “less spontaneous” with friends. That same night, then, he consoled himself with two whiskies (“I revel in these, wallow, smear, engorge myself”), and the next day he drove to the liquor store and replenished his gin.

Federico returned from Treetops after a week or two, and soon discovered that his father was drinking again. Caught in the act, Cheever said that Dr. Mutter had allowed him to have two drinks a day; Federico didn’t buy it and demanded he stop. For a while Cheever drank furtively and somewhat moderately, and from time to time would even ask his son’s permission; this being denied—-emphatically—he’d sneak a drink anyway. Meanwhile he worked on the only real writing he accomplished that summer: a brief testimonial on the savory elegance of Suntory whisky, in return for which a Japanese PR man arrived one day with a case of the stuff. “I was nervous about it,” Federico recalled, “and I think in one of his moments of pique he told me he’d drunk some of it to hurt me.” Federico promptly poured the rest of it into the sink, then phoned his mother in a panic and begged her to come home right away. But of course it was too late—had always been too late, though Cheever promised once again to abstain. “The gin bottle, the gin bottle,” he wrote in his journal.

This is painful to record. I go to the post office and stay away from the gin shop. “If you drink you’ll kill yourself,” says my son. His eyes are filled with tears. “Listen,” say I. “If I thought it would benefit you I’d jump off a ten-story building.” He doesn’t want that, and there isn’t a ten-story building in the village. I drive up the hill to get the mail and make a detour to the gin store. I hide the bottle under the car seat. We swim, and I wonder how I will get the bottle from the car to the house. I read while brooding on this problem. When I think that my beloved son has gone upstairs, I hide the bottle by the side of the house and lace my iced tea.

By the end of August, Federico and Mary had exhausted their arguments and Cheever was drinking openly again. They avoided him in disgust, while he in turn felt sorry for himself and affected to look forward to Iowa. As he wrote a friend, “I’m not at all sure what I’m getting into or getting out of but there seems to be a time for departure and this seems to be it.”