The brilliant but obscure composer Schneidermann has disappeared, having walked out of a matinee showing of Schindler’s List never to return, leaving behind only Laster, his best student and only friend. Lest his mentor be totally forgotten, Laster rushes the stage during a performance of Schneidermann’s magnum opus and forces the audience to listen as he speaks of his mentor until dragged off by the police.

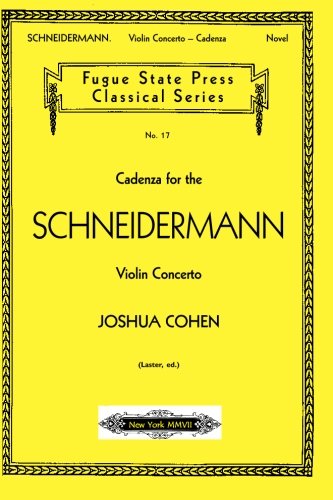

This is the entire plot, such as it is, of Joshua Cohen’s debut novel. A cadenza, he tells us in the preface, is an improvisatory solo passage near the end of the first movement of a concerto, one designed to showcase the virtuosity of the musician while exploring the themes of the main work. Laster’s hours-long testament to his vanished Schneidermann is the cadenza of the novel’s title.

Laster speaks in a familiar voice, that of the Elderly Jewish Raconteur: foreign born, world weary, worldly, old but still horny, he of the multiple ex-wives, mistresses, doctors, and lawyers. “Who do I think I am? / everywhere an international genius, a bearer-of-conscience-and-culture, once loved as much as respected. / But I’m no one, really.” It is through this voice that we will come to know Schneidermann; we can only imagine the themes of his life through referential snatches in Laster’s monologue.

The cadenza is not Cohen’s only classical conceit: paragraphs are broken like measures on sheet music; catchwords are used like musical cues—the first word of each page is listed at the foot of the page before it, so that the reader can turn the pages quickly without losing pace with the piece, just as a musician reads a printed score. Still, it’s easy to get lost. Laster is an avalanche of words, speaking in sentences that run on for pages. He digresses within digressions with aggressive wordplay: “[L]ike Harpo Marx Schneidermann was, at least a priest of the luftmensch’s namesake, Harpocrates…”

Cadenza is as much a meditation on Jewish identity as it is the story of one forgotten composer, which is fortunate, since Laster spends as much time speaking about himself as he does about his Schneidermann. Like most postwar reflections on the diaspora, the Holocaust casts a long shadow over the story. Laster managed to escape to London, but Schneidermann ended up in the camps. Both emigrated from the old world to the new, where they met again in the incomprehensible morass of postwar America. Aside from music, their only solace is each other. And movies. The film from which Schneidermann beat his unexpected exit was the last in a decades-long series of regular engagements. Together they sought refuge from the chaos of a constantly changing culture in the clichéd predictability of its matinees.

While this story is simple enough, Laster’s narrative remains anything but. Thankfully, though occasionally exhausting, it is also very entertaining. His opinionated ramble touches on everything from the categorical inferiority of Asian classical performers (“they think music and they play math”), to the failings of Spielberg movies (the schmaltzy score to Schindler’s List dishonors the Holocaust; the “little arms” on the T-rex in Jurassic Park “make it look like a homosexual”). Though mad with grief and mad at the world, Laster is still a performer. He repeatedly comments on the steady exodus of his audience, but seems interested in keeping them there.