Features:

- Definition in Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary: past tense and past participle of wake

- Definition in African American Vernacular English (AAVE): “well-informed, up-to-date”

- First print appearance of the AAVE usage: 1942

In the late ’90s and early aughts, the word woke was a life vest. My parents and the other black people I grew up with used it to stay afloat in a Wisconsin town whose university once feigned diversity by photoshopping a black man onto the cover of an admissions brochure. We ended our talks about redlining, racial profiling, Abner Louima, and Amadou Diallo with a reminder to stay woke. The word was a command to keep ourselves informed about anti-blackness, and to fight it. It acknowledged that being black meant navigating the gaps between the accepted narrative of normality in America and our own lives. Even the sound of the word woke kept me on my toes. When I heard it, I felt a pinprick. A probing finger in my side.

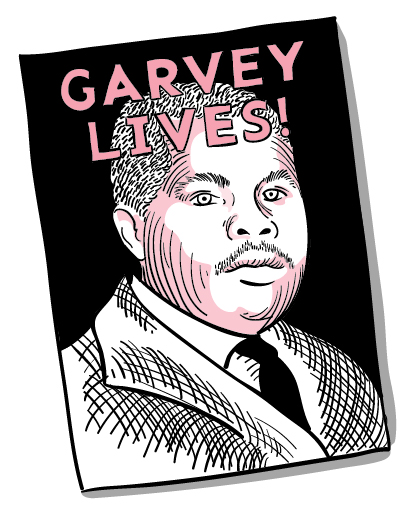

The Oxford English Dictionary credits William Melvin Kelley with the first printed, political use of woke, in a 1962 New York Times article titled “If You’re Woke You Dig It,” about white cooption of black language. But twenty years earlier, in a 1942 edition of Negro Digest, J. Saunders Redding used the term in an article about labor unions. A black, unionized mine worker told him: “Waking up is a damn sight harder than going to sleep, but we’ll stay woke up longer.” Barry Beckham’s 1972 play Garvey Lives! is often cited as another early example of the word’s political meaning. A character exclaims, in reference to Marcus Garvey, “I been sleeping all my life. And now that Mr. Garvey done woke me up, I’m gon stay woke. And I’m gon help him wake up other black folk.” This is the version of woke that I grew up with: a call to study and act against anti-black oppression.

In 2008, mass audiences discovered the phrase “I stay woke” in the popular Erykah Badu song “Master Teacher.” Six years later, after the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner, “Stay woke” became a rallying cry for the Black Lives Matter movement. But with its mass adoption, the word’s black activist history has faded, and its urgency has dulled. Now it functions merely as a nod to the speaker’s mainstream lefty positions, a smug confirmation that the speaker holds the expected progressive beliefs. What’s been left out is any reference to the structural and political systems that caused black leftists to adopt progressivism—or any understanding that maintaining woke views requires continuous work.

These days, if people aren’t born woke, exactly, they don’t need to do much to claim wokeness, either. In 2016, MTV defined woke as “being aware, specifically in reference to current events and cultural issues,” a definition broad enough to encompass everything from studying up on prison reform to remembering the last rap beef. Lyft is woke—because John Zimmer, the company’s president, said so. One of the cash registers at the Whole Foods in my neighborhood declares, via a fluorescent lamp on its side, that it’s “staying woke.” Even Alex Jones, at the 2016 Republican National Convention, claimed that he was “100 percent woke”—whatever that could possibly mean to a man who denies the reality of the Sandy Hook shooting.

This dilution of the meaning of wokeness has left the word open to attack. The newest usage of woke is as a pejorative, uttered sarcastically or dismissively in order to target perceived liberal intellectual elitism. The implication is that those who say they are woke are naive, hopelessly idealistic, or hypocritical. But to use woke as a buzzword or a sarcastic undercutting is to fail to recognize its power. Its traditional usage refers to staying abreast of the ways in which black people’s lives are devalued under white supremacy. But the current iteration of white supremacy in our country devalues pretty much everyone else’s lives too. Today’s white supremacy starves the poor, withholds medical care, and causes harm to women, immigrants, and all people of color. The majority of people in this country ought to be staying woke to the economic and political forces that threaten their civil rights and well-being.

The original meaning of the word woke deserves a resurrection. The seeds for it are in our activism, our art, and ourselves: in Colin Kaepernick’s public protest, in the work of Black Lives Matter and other black- and person-of-color-led organizations, in the art and music of Kara Walker, Kehinde Wiley, Kendrick Lamar, and Solange. But wokeness has always begun with the self. I had lunch with a friend last week, and after we traded stories about jobs and marriages and the news, we switched, as is our custom, to the topic of police brutality. “Stay woke,” he told me at the end of our conversation. It was the first time in a while that I’d heard those words, but they still held their old power. An electric hit went up my spine.